In the 1950s it was widely believed that the first Australians had arrived on this continent only a few thousand years earlier. They were regarded as “primitive” — a fossilised stage in human evolution — but not necessarily ancient. Over the past sixty years, the field of Australian archaeology, led by the likes of John Mulvaney, Isabel McBryde and Rhys Jones, has dramatically enlarged our understanding of Australian history. It is a story that has emerged from rock shelters and shell middens, art sites and urban spaces, archives and laboratories, lore and local knowledge. It is a complex, contoured and ongoing history of human endurance and achievement in the face of great social, environmental and climatic change. And last week, in a landmark Nature paper, it was pushed back to 65,000 years.

Dating the earliest human occupation at 65,000 years ago is a dramatic step, and it throws up questions that are not easily resolved. But it is not, as one journalist declared last week, “so old it [will] rewrite everything about the continent’s human history”; nor is it, as dozens of reports have asserted in their headlines, “evidence of Aboriginal habitation up to 80,000 years ago.” Such overstatements come from an unhelpful view that older is better; they diminish the site by emphasising numbers and dates rather than the deep and dynamic history they reveal.

The site at the heart of the latest finds, Madjedbebe (formerly Malakunanja II), has been part of archaeological conversations for over forty years. It is no more than a slight overhang: a decorated rock wall leaning out from the Arnhem Land escarpment, the last reach of the plateau before the landscape gives way to wet, scrubby plains. It lies on the lands of the Mirarr people, who were supportive of the archaeological work on their country. Through the Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation, the Mirarr held the right of veto over all aspects of the work and were involved in the excavation through a process of constant and respectful communication. As David Vadiveloo, a lawyer, film-maker and consultant to the corporation, put it: “the Mirarr did not want this to be a project about them, they wanted this to be a project that was in partnership with them.”

Madjedbebe was first excavated in 1973 during research for the Alligator Rivers Environmental Fact-Finding Study, a wide-ranging report that provided the case for the declaration of Kakadu National Park. Bill William Miyarki guided the young archaeologist Johan Kamminga to the rock shelter and, equipped with a trowel, ash shovel and brush, Kamminga dug a small test pit, to a depth of 268 centimetres, against the rock face. The deposit was rich with stone, shell and bone, and a carbon sample collected above the level of the lowest artefact led him to conclude that “the earliest occupation at [Madjedbebe] is therefore likely to be in excess of 18,000 years.” It was one of a series of Pleistocene sites identified along the Arnhem Land escarpment in the 1960s and 1970s, and there were many, including Rhys Jones, who believed the region might hold the key to dating the arrival of the first Australians.

By the time Madjedbebe was next excavated, in 1989, the time horizon for Australian archaeology had been pushed back to 37,000–40,000 years, but that was where it plateaued. Jones thought it was no coincidence that the oldest dates all clustered around the time when the material required for dating — the radioactive isotope carbon-14 — had almost completely decayed. He suspected that the oldest dates “were so close to the theoretical limits of the radiocarbon methods that maybe the ‘plateau’ was really an illusion.”

In an attempt to break through the radiocarbon barrier, Jones teamed up with geochronologist Bert Roberts and archaeologist Mike Smith to date a few known sites with the relatively new techniques of thermoluminescence and optically stimulated luminescence, which could date quartz grains from a few hundred years old to several hundred thousand years old. They returned to Madjedbebe and, under the watchful eye of Gagudju elder Big Bill Neidjie, dug a narrow “telephone booth” shaft, four-and-a-half metres straight into the earth.

The findings from the 1989 dig, published in Nature, suggested that people had been living in Australia for 55,000 years, plus or minus 5000. Jones often spoke of a human antiquity in Australia of 60,000 years. He revelled in the fact that this was 20,000 years earlier than any modern human site in Europe: it “really caused people to raise their eyebrows.” The news made headlines around the world and a commendation was passed in the Australian Senate noting, “with interest, the discovery of Dr Rhys Jones of the Australian National University, and his team, of art and artefacts in the Malakunanja II [Madjedbebe] rock shelter in Kakadu that have been dated as at least 60,000 years old.”

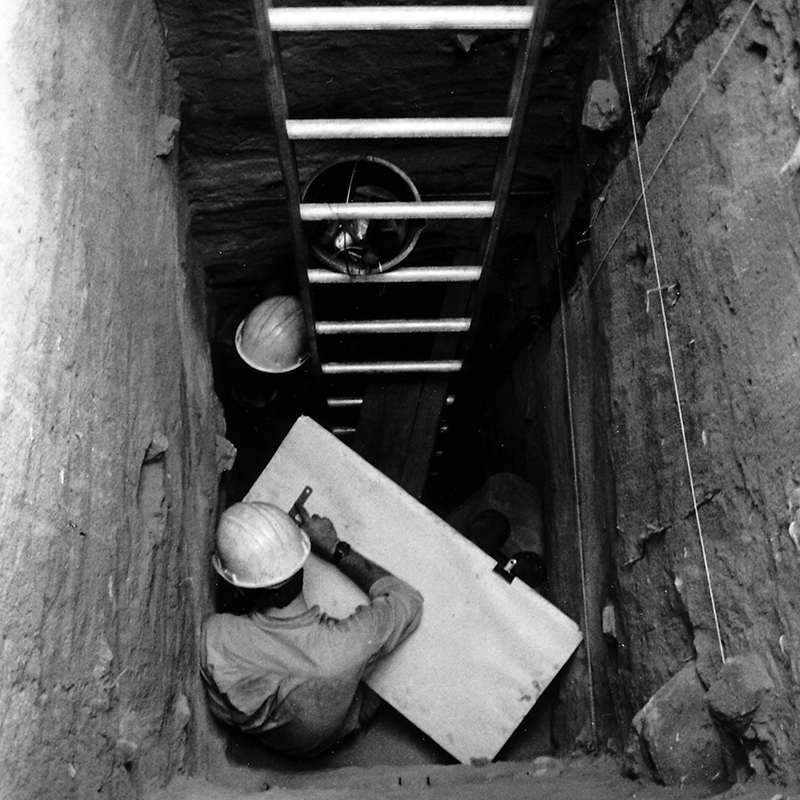

Archaeologist Mike Smith draws stratigraphy during the 1989 excavations at Madjedbebe (Malakunanja II), Arnhem Land. Courtesy of Mike Smith

But the archaeological community remained sceptical. Some criticised the work for the use of the relatively new method of luminescence dating; some for the fact that the 1989 dig was never written up with a full site report. Others questioned whether the artefacts at the lowest levels had been pushed down over time by termite activity or “human treadage.” Although another site excavated in the region, Nauwalabila, was published in 1994 with dates 53,000–60,000 years old, both sites were contested and their ages dismissed as outliers.

The rejection of the significantly older dates from Madjedbebe and Nauwalabila reflects archaeologists’ caution about accepting dates that are outside the general pattern of the oldest sites. In 1998, archaeologists Jim Allen and Jim O’Connell reviewed the evidence for early dates in Australia and concluded that “initial occupation dates to about 40,000 radiocarbon years ago.” In 2004, they pushed this date back a few thousand years, writing that “while the continent was probably occupied by 42–45,000 BP [Before Present], earlier arrival dates are not well-supported.” In 2014, they reviewed new claims and again updated their estimate, concluding that “the first humans arrived in Sahul shortly after 50 ka [thousand years ago] — on current evidence not earlier than 47–48 ka.” The incremental shifts from 40,000 to 42,000 to 45,000 to 48,000 led anthropologist William F. Keegan to remark wryly, “Archaeologists seem to face far more complications in making the crossing to Sahul than the people who accomplished this feat about fifty [thousand years ago].”

In 2012 and 2015, a team of archaeologists embarked on new excavations at Madjedbebe with the hope of resolving the lingering questions about the antiquity of the site. I joined the team as camp manager and cook. As well as subjecting the site to rigorous dating tests, my companions conducted a series of tests to verify its structural integrity and better understand the natural processes by which it had formed. By opening a larger area of the site, not just a small shaft, they were also able to gain a more nuanced picture of the archaeology at its deepest levels. The leader of the excavation, Chris Clarkson, was eager to see if he could discern a pattern in the lowest layers that might illuminate the technology of the first colonisers of Australia.

In the new Nature paper, the large interdisciplinary team carefully and systematically address the earlier criticisms of Madjedbebe, present an account of their remarkable technological discoveries and, through an exhaustive dating process, push back the baseline date for human occupation to 65,000 years. It is significant that many who were critics of the 1989 excavation, and who were not involved in the recent study, have spoken publicly of the robustness of the find. “This is the earliest reliable date for human occupation in Australia,” Peter Hiscock, the Tom Austen Brown Professor of Australian Archaeology at the University of Sydney wrote to one reporter: “This is indeed a marvellous step forward in our exploration of the human past in Australia.”

So what do we do with an outlier that refuses to be dismissed? Madjedbebe’s 65,000-year story allows us to calibrate the epic journey of our ancestors, homo sapiens, out of Africa. The colonisation of Australia was no small feat. It required the traverse of a passage of water around one hundred kilometres wide to a land where no hominid had roamed before. Based on the array of technical, symbolic and linguistic capabilities it required, psychologist–archaeologist duo William Noble and Iain Davidson have argued that “archaeologically, this is the earliest evidence of modern human behaviour.” Thus, the endless debates surrounding when modern humans emerged from Africa and spread around the world ultimately come to rest on when people arrived at the southernmost extremity of their migration. Madjedbebe becomes the key date.

The antiquity of the site also thrusts it into the longstanding debate over the fate of the giant marsupials and reptiles known as the “megafauna,” which, according to a large-scale dating effort in 2001, died out in a continental extinction around 46,000 years ago. Talking to the media this week, Clarkson was emphatic: “It puts to bed the whole idea that humans wiped them out. We’re talking 20,000 to 25,000 years of coexistence.”

But it is important to stress that the history uncovered at Madjedbebe enriches, rather than eclipses, archaeological understandings of other regions. The new, older date doesn’t necessarily destabilise the strong pattern of settlement that has been established by archaeologists across Australia from 50,000 years ago; rather, it reveals how little we know about the 15,000 years that preceded it. Around 65,000 years ago, the first Australians were probably swept to the Sahul Rise: a low-lying, fan-like formation of skeletal limestone, riddled with tidal channels. The landing site, along with many signs of early occupation, now lies submerged on the Arafura Sea shelf. It is only though the lowest layers at Madjedbebe, at the margins of this vast inundated region, that we can glimpse the earliest chapter of Australia’s human history. “It’s not exactly Atlantis,” Mike Smith and Chris Clarkson remarked to me, “but it’s pretty bloody close.”

The full implications of the latest findings from Madjedbebe will take time to absorb. But let us not be dazzled by old dates — nor become numb to their power. Madjedbebe’s 65,000-year story adds to a remarkable Indigenous history of transformation, resilience and diversity. •