Like their Sydney-based Rugby League counterparts, the twelve Australian Rules clubs that made up the Victorian Football League, or VFL, were rooted in local loyalties and intense emotional attachments. But by the early 1980s rising player payments, steep transfer fees and poor management had pushed perhaps half of them to the brink of insolvency. They were ripe to be swept up in the corporate spirit that characterised the decade.

In 1984 the high-profile businessman and Liberal Party identity John Elliott, president of the Carlton Football Club, led an initiative to form a breakaway league. The VFL responded by changing its governance structure and redoubling its efforts to corporatise the sport. Pressure mounted to close grounds and merge clubs, or to move some clubs interstate to tap into new “‘markets.” Fitzroy — a team based in an old but now gentrifying inner suburb — was still enjoying fair success on the field in the mid 1980s but only narrowly averted an attempt to move it to Brisbane in 1986 (a move that would eventually be forced in 1996).

Efforts to merge or move clubs provoked lively grassroots resistance on the part of supporters for whom the Saturday afternoon ritual was a link not only with a loved place — the home ground — but also with a way of life pursued by their parents and grandparents. The defiant and successful movement in late 1989 to save the struggling western suburban Footscray from a merger with Fitzroy drew on loyalties to class, club and community, a sense that others looked down on the western suburbs, a feeling that malign forces were trying to destroy something precious and loved.

For those who fought to save Footscray, one of the problems was the VFL’s obsession with creating a national league, one that would extend the code — or “product” — to Sydney and Brisbane as well as encompass the major football-playing states of South Australia and Western Australia. By 1991 what was now called the Australian Football League included clubs from all five mainland states.

For a time it seemed that rich men would become not merely the presidents but also the owners of teams. The major experiment of this kind involved the Sydney Swans, a club that emerged from the northward relocation of the declining South Melbourne team in 1981. The effort to place the Swans on a secure financial base and promote the game to a Sydney audience flushed out “medical entrepreneur” Dr Geoffrey Edelsten, then unfamiliar to most members of the public but better known to the Australian Taxation Office.

Since graduating in medicine from Melbourne University, Edelsten had enjoyed a colourful if rather chequered career as a medico, businessman and playboy. He had produced pop records, owned a nightclub, established his own flying doctor service, run health studios, set up a high-tech pathology laboratory in the United States, and offered a Family Health Plan in Sydney — which looked to police rather like a medical insurance business minus the necessary licence. He had even sponsored the Bluebirds, a troupe of dancing girls whose presence at Carlton home games was intended to add an American-style razzamatazz and sexiness.

By the mid 1980s — now grey-haired but still with an eye for female talent — he had married a professional model, Leanne, more than twenty years his junior. Edelsten was now best known for operating a chain of Sydney surgeries that, in their decor and design, had more in common with brothels than most people’s image of a humble general practitioner’s rooms. But then Edelsten was no humble general practitioner, even if all his patients needed to do to enjoy the luxurious facilities provided by “the Hugh Hefner of medicine” was to flash their green and gold Medicare card.

“His surgeries are decked out in gold, with salmon pink velvet couches, enormous chandeliers and mink-covered examination tables,” reported one journalist. “Gold-clad hostesses and a small robot offer refreshments and educational advice to patients, who are told that if they wait more than ten minutes to be attended to they are entitled to a free Instant Lottery ticket.” The surgeries also came with white baby grand pianos; a pianist was sometimes paid to entertain patients while they waited.

The glitz of the surgeries was matched by the Edelstens’ private life. There was the $6 million home in Dural and luxury cars with numberplates that said “Macho,” “Spunky” and “Groovy.” And there were Edelsten’s gifts to Leanne, which supposedly included a pink helicopter — that it was pink Edelsten always denied, but many people swear that they saw it — and, the Daily Telegraph reported, “a $100,000 pink Italian sports car lined with white mink.”

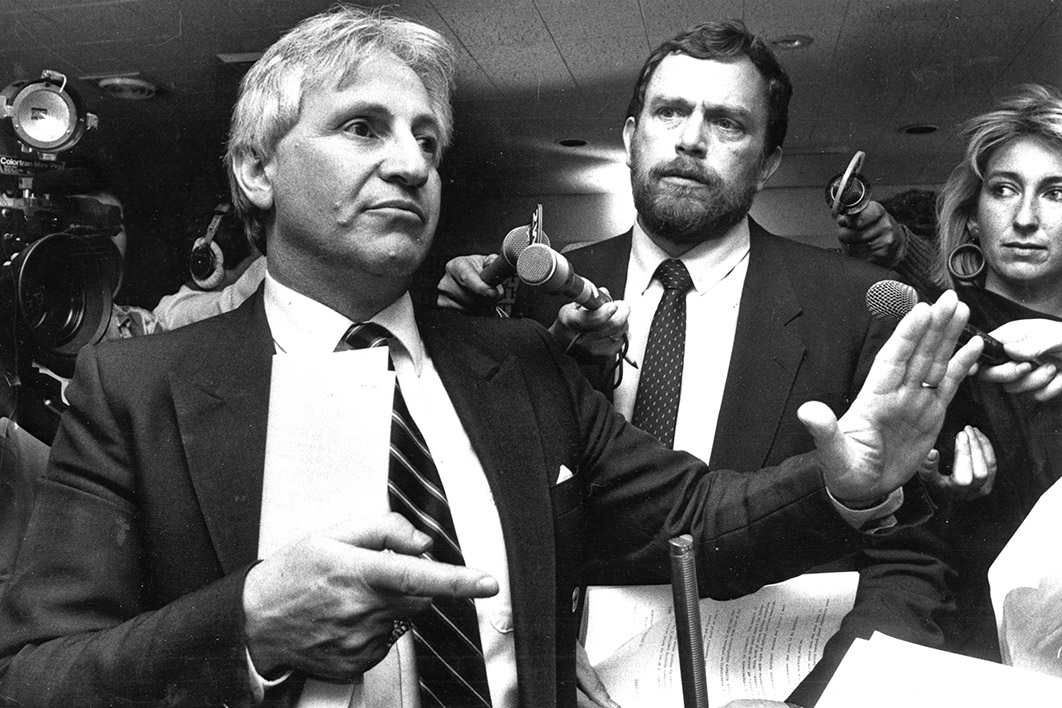

In late July 1985 the VFL agreed to award the licence for the Swans to Edelsten in preference to the bid of another businessman, Basil Sellers (a man “of much more conservative bearing,” according to the Canberra Times). The league needed to get the Swans noticed in a tough market, and Edelsten appeared to be just the kind of showman capable of helping it out. Indeed, the syndicate to which he belonged played up the glamour as a means of distinguishing itself from the other bidders. It promoted the Edelstens as embodying Sydney’s colour, playfulness and hedonism in contrast with the sober restraint of Melbourne. Edelsten exuded flamboyance, wealth and success, and Leanne — present when her husband learned that his Swans bid had been successful and wearing, according to one report, “a sequined white jumper, red leather pants and wet-look white thigh-length boots” — was central to his image.

Media reports said the price was $6.3 million, a figure that casual observers assumed had been carved out of a much greater fortune, but it soon became clear that the deal was a rather more tangled one. Edelsten eventually handed over about $3 million, mainly other people’s money. It looked increasingly as if he was really a frontman for other interests, but there was no denying his ability to attract notice. He was helped by a spectacular, long-maned, blond full-forward named Warwick Capper, who wore striking white boots and shorts even tighter and more revealing than the usual skimpy kind. He, too, briefly became an image of Sydney spunkiness and flamboyance.

Edelsten’s association with the Swans gave his surgeries publicity that allowed him to evade the prohibition on doctors advertising their services, but it was the doctor’s business interests outside football that caused him problems soon after the award of the licence. A Labor senator, George Georges, alleged under parliamentary privilege that Edelsten was the “Dr X” named in a parliamentary committee report as being investigated for medical fraud. Edelsten took out a full-page advertisement in the Sydney Morning Herald declaring his innocence. An exposé of Edelsten’s business methods in the satirical magazine Matilda, which imputed various forms of lurid criminality, added further damage and provoked a lawsuit.

Worse followed: Edelsten soon stood accused of having hired the notorious hit man Christopher Dale Flannery to assault a patient who had given him trouble. He had already stood aside as Swans chairman but still had a long way to fall. He subsequently became bankrupt, divorced, and was struck off the medical register and sent to prison. And as the 1980s passed into mythology, his and Leanne’s lifestyle was seen to epitomise the era’s excesses. •

This article draws on The Eighties: The Decade That Transformed Australia (Black Inc., 2015).