To the left of the National Library of Australia’s main entrance steps you will discover the modest foundation stone laid by Sir Robert Menzies fifty years ago, on 31 March 1966, when the library building was still a five-storey steel shell. Modest, that is, compared with the plaque that marked the grand opening of the building by prime minister John Gorton on 15 August 1968.

If celebrations that day in 1966 belonged principally to the national librarian, Harold White, the foundation stone ceremony represented a pinnacle for Menzies. Yet the words “prime minister” do not appear on the stone, because Sir Robert, aged seventy-one, had resigned his office and handed over to Harold Holt two months earlier, a fact that required an unexpected rewording of its text.

So why did Menzies lay the stone, overturning the protocol appropriate to Holt’s office? It’s true that both the new and the old prime minister appeared with their wives on stage, alongside interior minister Doug Anthony and the chair of the Library Council, Sir Archibald Grenfell Price, but it was Menzies who retained the starring role.

It was a celebratory and fitting finale for Menzies, for his vision and leadership underlies the backstory of the approval, timing, design and construction of this monumental building on its remarkable lakeside site. The Canberra Times headline captured it that day: “Dream Library Takes Shape.”

Menzies never claimed the vision of the National Library as his own – neither the Library’s independent governance nor the building. For that, he acknowledged Harold White and Sir Archibald Grenfell Price as tenacious leaders among many cumulative forces. As he said in his speech, the legislation establishing the Library and the associated Australian Advisory Council on Bibliographical Services was a “statesman-like act” of national cooperation. Yet it was Menzies’s conviction and authority that carried the day with his cabinet colleagues, shaped and overrode the decisions of the National Capital Development Commission, or NCDC, and conveyed the vision of why a great National Library mattered.

In a remarkable speech that he wrote himself and typically delivered only from notes, Menzies asserted with considerable force that the real value of the library lay not in the monumental building, despite its symbolic beauty, grandeur and classical dimensions. Rather, its true quality and international stature lay in the collections contained within the building. These were the “great interpreters of the past to the present… the present to the present… and the present to the future.”

The foundation stone celebrations in the unfinished foyer, 31 March 1966. National Library of Australia, nla.obj-136760604

Perhaps in a gibe at those who relied on mere statistics about the size of the collection – a way of measuring its value to which “we must not succumb” – he asserted that it was “the use that is made of [the books], the value that is attached to them, the quality that they exude which will in the long run determine the character and status of the library concerned.”

Menzies extolled the library as a “source of light for scholars, for thinkers… it will have a great international significance,” the corollary of governmental efforts to forge research and scholarship in the nation. Through the library’s collections, “we [are] learning from the past, we [are] learning from each other, we [are] helping to instruct and inform the future; this is the most tremendous process in the human mind.”

The concept of the building as a national monument had long preoccupied Menzies, whose role in the decision-making was pivotal.

The existing National Library had been established as part of the Parliamentary Library at Federation in 1901, and was modelled on the US Library of Congress. It was overflowing, scattered in fifteen buildings that radiated from its inadequate Kings Avenue building. Menzies established two inquiries that directly affected the decision on where and when to build a new National Library. The first, a Senate inquiry into the development of Canberra in 1955, resulted in the establishment of the NCDC in late 1957. The second was the Commonwealth inquiry into the National Library. It was this second inquiry, led by Professor Sir George Whitecross Paton, vice-chancellor of the University of Melbourne, that recommended the formal separation of the national and parliamentary libraries.

On 10 November 1960, Menzies introduced the National Library Bill into the House of Representatives, identifying its separate function as a “national institution independent of parliamentary connections.” But there was no commitment, yet, to a new building. The NCDC’s priority was to build – or at least plan – the new Parliament House. Menzies’s political judgement was that the populace would not support such expenditure for parliament; thus, also, no new library.

Menzies did agree, though, with the NCDC’s preferred lakeside site, and the symbolic power of the location. Imagine, then, what Menzies’s dream looked like in 1966 as he laid the library’s foundation stone. Remarkably, it was the first of the big national monuments to be built on the newly filled lake.

“I’d like to live long enough to be brought along in a wheelchair or ushered on to a boat on the lake,” Menzies reflected as he laid the stone, “to see this building in all its white beauties standing here, reflected in the lake. To see a Parliament House of noble dimensions and to see a High Court in the place that’s been described.”

What was this symbolic concept of place? Once the major buildings were completed, Parliament House would be in the centre, standing by the lake, a symbol of freedom and democracy. It was to be flanked by two monumental buildings of lesser scale, representing the independence of the judiciary – the High Court – and the independence of the mind – the National Library. Behind those two buildings would sit Treasury (developed at the same time as the library) and the Administrative building (now the Sir John Gorton building), designed to serve the government.

Harold White wrote:

This relationship of the Legislature, the Judiciary and of a National Library has impressed many of us as a symbolic one, of special significance in a country which has long been devoted to Parliament and the Law, but only recently convinced of the need for research and inquiry to support our national growth.

This tripartite symbolic plan had been an accepted part of the NCDC’s design of the parliamentary triangle since at least 1960. It had prevailed over competing recommendations that Parliament House should sit on Capital Hill – the dominating summit above the temporary (Old) Parliament House – which some viewed as the appropriate landscape for a “Capitol” much like Washington’s. (Canberra’s designer, Walter Burley Griffin, considered, but dismissed, this option.)

The decision on where to site a “great National Library” was intrinsically linked to where the new Parliament House was to be located – a fact affirmed by a small and often overlooked design detail in the 1961 architectural briefs for the library, found in Sir Harold White’s papers. A tunnel was originally intended to link the library to Parliament House so that items from the collection could be readily delivered. Menzies’s personal papers testify to his own extensive use of the library’s collections, and in his foundation stone speech he passionately affirmed that a life without books was unimaginable: clearly he understood the perspective of users, scholars and researchers. Here was a prime minister deeply engaged with the functions and meaning of the library.

The inaugural commissioner for the NCDC was Sir John Overall, previously chief architect, whom Menzies appointed in February 1958. In a 1973 interview, Overall provided fascinating insight into the “sorrowful state” of Canberra’s housing, schools, community infrastructure and transport, and the lack of commercial enterprise in the 1950s. He also recalled the divisions in cabinet and within the bureaucracy managing Canberra and its public service workforce, and Menzies’s redoubled determination “to design, develop and construct Canberra as the National Capital of Australia.”

Though the story of the heady construction program that ensued is well known, Menzies’s personal motivation reflected a more intimate perspective. Overall recalled that Menzies’s daughter Heather was to marry diplomat Peter Henderson in 1955 and they were planning to return to Canberra from the Australian embassy in Jakarta. Menzies and his wife Pattie walked Canberra’s broken or non-existent pavements looking for a suitable home for them. Even though he lived in the Lodge, Menzies didn’t really “know Canberra,” according to Overall. What he found during his walks “appalled” him, and it was this personal investigation that prompted him to set up the 1955 Senate inquiry into the future development of the national capital.

In 1957, Menzies asked Britain’s most influential planner, Sir William Holford, to provide advice to the Commonwealth, especially on the development of the parliamentary triangle. While the Senate inquiry’s report had argued for the Capital Hill site for parliament, it was Holford who recommended the development of the lake. He believed that its symbolic, functional and visual centrality made it the prime site for the new Parliament House and its related buildings. The NCDC affirmed these principles in its Report on Sir William Holford’s Observations on the Future Development of Canberra.

Holford was silent on the matter of the library site. The talk of the day had become rather more pragmatic, and one prevailing view was that the National Library should “take over Provisional [Old] Parliament House when the parliament transfers to its permanent home.” The speaker of the House of Representatives and the president of the Senate had first recommended this in 1956, in a private submission to Menzies on “The Case for a Permanent Parliament House,” which was discovered among White’s papers. Menzies had succumbed, despite the persistent advocacy of White and his cohort of supporters for a new, grand building.

From June to August 1958, Alister McMullin, president of the Senate and chair of the Parliamentary Library Committee, John McLeay, speaker of the House of Representatives, and members of the Library Committee vehemently supported Harold White in an exchange of letters with Menzies. They urged the prime minister, as a matter of urgency, to separate the National Library’s governance, collections, staff and records from the Parliamentary Library, to bring the 1952 plans for a new National Library building up to date, and to agree on a suitable site.

Later, in a 1967 speech, Harold White recounted just how long a suitable library building had been in the offing. It dated back to the ceremony presided over by prime minister Joe Lyons on 24 November 1934, when governor-general Sir Isaac Isaacs and the British poet laureate John Masefield laid the foundation stones for the first Library building in Kings Avenue. Christine Fernon recounted this epic story in National Library News on the fortieth anniversary of the building: in Harold White’s words, the library “staggered out of the Wilderness.”

By 1959, cabinet had agreed that the commencement of a National Library building could be included in the NCDC’s plans, but only in the latter part of its five-year planning period. In 1960, cabinet still took the view “that it would not be appropriate… for the Government to give an indication of adding a new and substantial library building to the Canberra programme.”

What changed Menzies’s mind between then and August 1961, when he himself brought a submission to cabinet at the request of the Library Council? Almost certainly he had private meetings about the matter. Sir John Overall reported that Library Council chair Sir Archibald Grenfell Price had a long conversation with the prime minister about the building. “He reported a sympathetic hearing,” observed Overall. “It was agreed that preliminary planning should proceed, to the extent of defining a program and establishing the site.” Cabinet finally gave in on 12 September 1961 in response to Menzies’s submission. It agreed to appoint an architect to design the building and prepare working drawings, although it made no commitment beyond approval of the initial design phase.

Menzies clearly intervened personally and abruptly in the decision to bring forward the National Library building in the NCDC’s plans and priorities, as well as to escalate the size, scope and splendour of the building on the prestige site where it stands today.

While the official records document the decisions, the behind-the-scenes story of why and how Menzies influenced the planning is never quite revealed, leaving some elements to speculation and imagination. Manuscript collections, cabinet papers, submissions and committee minutes, unpublished reports, architectural plans, building specifications: all can be scoured to piece together the official sequence of events. But it is oral histories that fill in some of the gaps and add personal nuance to the story.

Peter Biskup’s interview in 1988 with Dan Sprod, the library’s liaison officer for the building project at the time, and later chief librarian at the University of Tasmania, is the most potent source for details of Menzies’s intervention. Despite the distance of time and a slightly faltering memory, Sprod recalled the development of the architectural briefs for the building, in which “Harold was up to… his ears” advocating for a large building that would accommodate long-term collection expansion. Sprod observes, however, that the NCDC “was trying to cut us down to the bare bones, and instead of a grand building, we were going to have a very utilitarian building [perhaps on a different site].”

“We had two meetings on consecutive days,” he told Biskup:

And on one meeting… the NCDC through Overall was going through this deprecating business of knocking us down and clipping our wings. The next day we had another meeting, and Overall started talking and I sat there, and it took me a while to realise that something had happened overnight.

And… without even saying, look we’ve looked at this again and we think you’re right, he was starting to accept all the library’s arguments for a grand monumental building on a prestige site…

I didn’t tumble to it for a while. And, of course, what had happened overnight was that Overall had been called in by Menzies and told that the National Library was to be a grand building, a flanking building for the Parliament House, and to balance the High Court building, which was not then even planned, but you know, anticipated but not planned…

Definitely that was the reason why the National Library’s got that grand building today. It was a personal decision by the prime minister of the day.

Even Harold White was caught unawares. While overseas in late 1961, he was called on to make a “sudden and difficult decision” about a much grander building and how much land would be needed. He was very glad to have advice from Dr Keyes D. Metcalf, an international expert on library planning, who ratified White’s estimates based on his rapid consultations with staff at the British Library. Menzies had most certainly intervened.

By 1962, the site was finalised and the firm of Bunning and Madden had been appointed under chief architect Walter Bunning. Cabinet approved the working plans on 12 March 1963.

As the architectural concepts unfolded, it became clear that the noble, monumental and classical style of the building was much in accordance with Menzies’s taste. His approval, over the years, of treasured collection acquisitions also betrayed his love for and interest in all things “classical.” In approving the acquisition of academic bibliophile Sir David Nichol Smith’s collection in 1962, for example, Menzies added a note in his own hand: “As this is 18th century, I cannot say NO.” Menzies also had a hand in approving the artworks, including the commissioning of tapestries and sculptures.

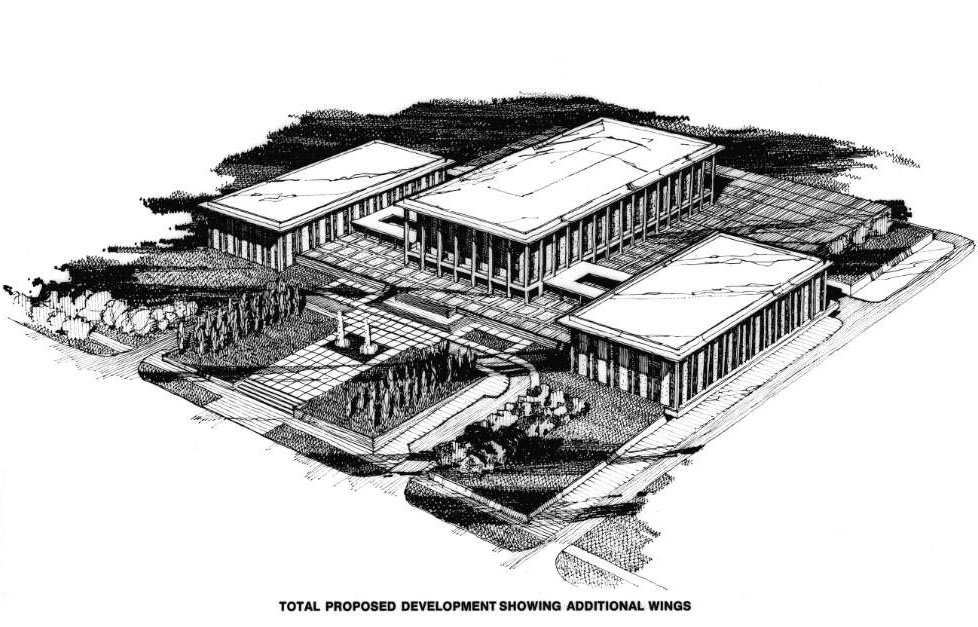

Total proposed National Library development, showing additional wings during original planning for size of land and building c. 1960. National Library of Australia, la.obj-136827452

From the announcement of the architects and the public release of the model and drawings, the Canberra public became enthusiastically engaged in the new lakeside building, all glowingly reported in the Canberra Times. On 25 July 1964, the newspaper reported that “workmen yesterday began pouring concrete in the construction of the new National Library.” The building work must have started almost instantly after Doug Anthony announced the contract with the builders on 17 April 1964.

By the time the foundation stone was ready to be laid in 1966, the steel shell was in place, with five storeys above ground and two filling the space below. Invitations were printed and sent; protocols and complicated lists of guests from all over Australia travelled between parliament and the library; arguments took place about seating plans, with an indignant Harold White relegated from the dais to the front row.

On the day, hundreds of excited individuals gathered for a momentous celebration. The speeches by Doug Anthony, prime minister Harold Holt (based on notes sent by Harold White) and Sir Archibald Grenfell Price recounted the context, the statistics, the epic story, the key players; all were recorded for posterity. Yet the day belonged to Menzies. After the event, the inner few retreated for an informal buffet dinner at the Whites’ home in honour of Sir Robert and Dame Pattie.

That date fifty years ago was the halfway point in completing the National Library building. But for Menzies it was the culmination of a vision dreamed not only by librarians and scholars, but also by a prime minister prepared to shape, guide and support his national monument. It was his testament to the importance and value of knowledge, worthy of a national capital and on behalf of his nation. •

An earlier version of this essay, with references, is available on the National Library’s website.