No one saw this coming. Last Thursday, an opinion poll told us that Victoria’s Labor government would win the Northcote by-election with room to spare, by 54 per cent to 46 for the Greens. But two days later, the voters did the reverse, and gave the seat to the Greens in a landslide.

At every polling booth, there was a swing of at least 10 per cent against the Andrews government. The average swing at the booths was 16 per cent. While some of that was clawed back on postal and pre-poll votes, by the end of the night, with only a few postals left to count, the government had lost the seat in a swing of 11.7 per cent.

This is the first seat any Labor government in Victoria has ever lost at a by-election. Indeed, it is only the third time in a hundred years that Labor in Victoria has lost a seat at a by-election; as Adam Carr’s invaluable Psephos website shows, the last was in 1948, when it lost Geelong in a campaign dominated by federal issues — rationing, bank nationalisation and the industrial war between the Chifley government and communist-led unions.

The loss of Geelong in 1948 presaged the fall of the Chifley government a year later. In hindsight, the Kennett government’s landslide losses in 1997 at the by-elections for Gippsland West and Mitcham foreshadowed its fall at the 1999 election, although none of us realised that at the time.

We’ve seen the same thing often enough at the federal level. Think of the Bass by-election in 1975, when a 14 per cent swing swept away former deputy prime minister Lance Barnard’s old seat, sending a clear signal that the Whitlam government would not survive its next election. Those who were alert received a similar message in 1995 when the Keating government lost its rusted-on seat of Canberra in a 16 per cent swing.

Losses like these are political earthquakes: they tell governments that the ground has moved from under them, and they too are likely to topple.

Could the earthquake on Saturday in Northcote spell the end of the Andrews government? Or do one-off factors suggest we should take it with a grain of salt?

Does the Greens’ huge win tell us that — even though they are losing ground in the opinion polls and political relevance — the inner-city tide that swept them to victory in the federal seat of Melbourne, the Victorian seats of Prahran and Melbourne, the NSW seats of Balmain and Newtown, and the Brisbane City Council ward of The Gabba is still surging in, and will sweep away more seats in the elections ahead?

Could the next Victorian election see the Greens take Brunswick and Richmond, giving them all of the five they set out to win five years ago? Could the next federal election see them take Batman, Melbourne Ports and Wills? Could Saturday’s Queensland election see a thirty-year-old Green unseat deputy premier Jackie Trad in South Brisbane, as the Galaxy poll suggests?

And suppose any of these coming elections sees the Greens win the balance of power — in Queensland, Victoria, New South Wales, or federally? Should Labor follow shadow treasurer Chris Bowen in insisting that it will govern alone or not at all? Or, instead, should it follow the example of its New Zealand and German counterparts, and set out to forge the kind of relationship with the Greens that will make them natural partners in a future government?

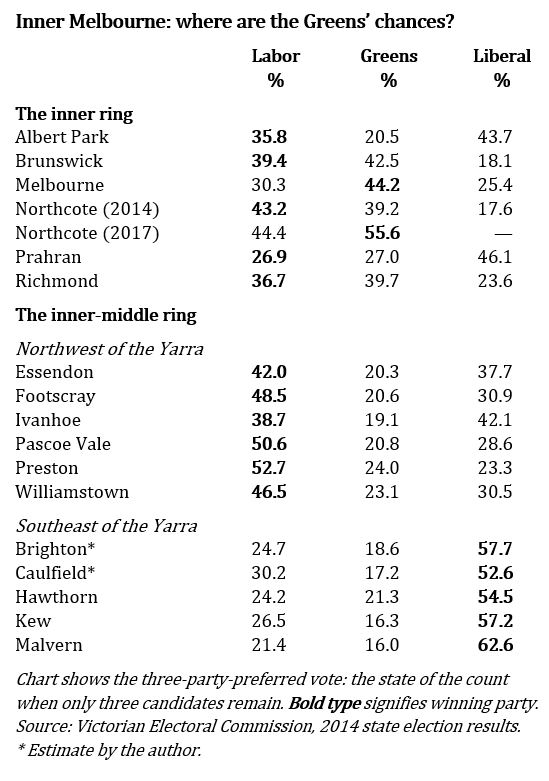

Let’s start with Victoria. In 2014 the Greens broke into the Legislative Assembly by winning Melbourne from Labor and — by the skinniest of margins — Prahran from the Liberals. They also topped the poll in Brunswick and Richmond, but Liberal preferences saw Labor scrape home in both seats: by 2.2 per cent in Brunswick and 1.9 per cent in Richmond. The Greens also expanded from three to five seats in the forty-member Legislative Council.

Of the four traditional Labor seats, Northcote was the one that most resisted the Green wave. Labor’s Fiona Richardson topped the 2014 poll, and held the seat with a 6.1 per cent margin. But her death from cancer three months ago led to this by-election, where the Green tide has reached a new high.

Labor insiders were stunned by the electorate’s rejection. Their candidate Clare Burns had gone down well with voters. They felt they had targeted their campaign precisely at the electorate’s priorities. Their dismay was all over Monday’s papers, along with hints that Labor might effectively give up fighting the Greens in the inner suburbs, and focus its 2018 election campaign on fighting the Liberals in the rest of the state.

But two unusual factors clearly influenced Saturday’s result, and should make us cautious about reading too much into the result:

⦁ The Liberals didn’t stand, so Labor didn’t get the benefit of its preferences. The absence of a Liberal candidate inflated the Greens’ share of the vote, and helps explain why the turnout was less than 80 per cent, down from 92 per cent at the last election.

⦁ On the previous Wednesday night, Labor’s central preselection panel overruled local branches and denied popular Brunswick MP Jane Garrett preselection for a seat in the upper house, presumably because of her resignation from the ministry after premier Daniel Andrews made a controversial deal to give the United Firefighters Union a big say in the deployment of firefighting resources. The panel’s decision was a slap in the face to Labor voters, telling them in effect, “You don’t run this party — we union bosses do!”

The reaction to this explains part of the gulf between the 54–46 vote forecast by the Reachtel poll on Thursday and the 44–56 outcome. But the poll’s failure reminds us that even the best of them, such as Galaxy and Newspoll, have a poor record on tipping individual seat outcomes. I doubt that Bennelong will be as close as the polls now forecast.

The Greens’ new state leader, Samantha Ratnam, singled out the ten seats mentioned above (five in each house) as the Greens’ target for the election next November. That’s sensible, because the tide is variable, and most of the Greens’ seats are held by very narrow margins. In Prahran, they edged out Labor by just thirty-one votes, then the Liberals by 277. Apart from an upper house seat in western Victoria, Brunswick and Richmond are the only potential gains within their reach.

As the table below shows, the Greens in 2014 didn’t come within cooee of winning any other seat. Moreover, far from Prahran’s being the first of many likely inroads into Liberal-held seats, its unusual mix of suburbs makes it the only Liberal seat the Greens are ever likely to win. Hawthorn and Caulfield may be outside chances in ten years’ time if enough young people move in, but Brighton, Kew and Malvern? Forget it.

Similarly, it’s hard to see the Greens ever winning upmarket seats like Albert Park and Ivanhoe from Labor, because both major parties have such strong bases there that the bar is higher. I suspect the Liberals will win both seats before the Greens do.

The reality is that, Prahran aside, the Greens’ growing strength in inner suburbs has come from winning votes and seats from Labor, not from the Liberals. And a realistic ten-year expansion plan for the Greens must focus on taking more seats and votes from Labor in its heartland, north and west of the Yarra.

Williamstown, Footscray, Essendon, Pascoe Vale and Preston form the next ring out. They’re all Labor now, but they are slowly shedding their old working-class base as cashed-up young homebuyers move in. They won’t go Green in 2018 or 2022; but in 2026? Maybe.

That task could become easier if the Liberals adopt the plan of their new state director, former Kevin Andrews staffer Nick Demiris, to stand no candidates in the inner city, and let Labor and the Greens fight it out. If that happens, Saturday’s vote in Northcote suggests the Greens would sail home in Brunswick, Melbourne, Northcote and Richmond. Labor would probably not waste many resources on those seats.

That would free up Green resources to fight in Prahran, and Labor resources to fight the Liberals in other areas. Maybe there is some genius in the Demiris plan that escapes me right now, but if I were the Liberal state director, I’d rather have them fighting each other than fighting us.

A report in the Australian implies that the Coalition’s goal is to whip up a scare campaign come election time about the risks of a Labor–Greens coalition. That was tried in New Zealand two months ago and didn’t work too well. Maybe Victoria is different, but it may also be the case that slogans that appeal to rusted-on Liberals don’t have the same attraction for the voters the party needs to persuade.

The increasingly likely bottom line is that Labor will only be able to govern after the next election in partnership with the Greens, as in New Zealand and the Australian Capital Territory, or as a minority government with some formal support. Realistically, both parties need to start thinking hard and talking informally to each other now, to get a sense of what might be possible and viable.

Right now, the Victorian election outcome next November looks to be a fifty-fifty proposition between the Coalition and Labor.

Before then, we could well have a federal election. And Greens federal leader Richard di Natale has set his sights high, claiming on Sunday that the party can win twenty-five federal seats over the next twenty-five years. (He’s unlikely to still be in the job to be held accountable if they don’t.)

Last year’s federal election saw the Green vote surge throughout inner Melbourne, making nonsense of a recent claim that the party has to focus on one seat at a time. It held Melbourne comfortably, came within 0.6 per cent of a potential boilover in Melbourne Ports, and won swings of 10 per cent in its neighbours, losing by just 1 per cent in Batman and 4.9 per cent in Wills.

If the Northcote result is any guide — especially if the Liberals sit it out, or split their preferences — the Greens could win all four federal seats in inner Melbourne. That’s if an election is called in the coming months, before the current redistribution is completed.

It’s always possible that one day the Greens might outpoll Labor to win the laid-back “alternative” northern NSW border seat of Richmond (where they also lost by 4.9 per cent last year). But there was no other seat in Australia where they came close.

In Sydney, they came second in Anthony Albanese’s seat of Grayndler, but still lost by 15.8 per cent. They came second in Tony Abbott’s seat of Warringah, but lost by 11.6 per cent. In Queensland, they went down by 7.5 per cent in Kevin Rudd’s old seat of Griffith, and 9.8 per cent in Brisbane. In Higgins they cannibalised Labor’s vote to come second with another 10 per cent swing; but to get the other 8 per cent they need to win the seat, they will have to win votes off the Liberals. They’re not good at doing that.

Bottom line: whatever their dreams for the next twenty-five years, the Greens have chances in just five seats at the next federal election. Four of them are in inner Melbourne — and their boundaries are about to be changed, perhaps dramatically.

The last federal redistribution in Victoria was one of the worst I’ve ever seen. It has ended up with massive disparities in the size of electorates — at last count, McEwen has 140,871 on its rolls, Bruce 95,315. The disparities mostly favoured one side of politics (the Coalition). And one electorate (Melbourne Ports) was gerrymandered to include suburbs the local member and his ethnic community wanted in the seat: an ominous development.

It’s to be hoped that none of that will happen this time. The redistribution commissioners on Monday released the sixty-seven “suggestions” forming the first round of submissions, including mine. And while at first sight the addition of an extra seat (reflecting Victoria’s rapid population growth) makes their task easier, allowing for more population growth in the near future shows it is in fact very difficult.

The rules try to make redistributions fair. They require commissioners to design the seats so that, after three and a half years, all seats will be within 3.5 per cent of the average. (In Victoria last time, by that stage, fourteen of the thirty-seven seats were already out of whack.) If we assume that Victoria’s growth will be something like what it was in the last three and a half years — well, I won’t bore you with the details, but that will require them to design electorates that cross the Yarra. Motorists and commuters do it every day, but so far it’s been a red line for Victorian redistributions.

And where is it sensible to cross the Yarra, given that the commissioners are expected to group “communities of interest”? The obvious places are at both ends — the bush suburbs out near Eltham, and the inner city at Southbank (now in Melbourne Ports) or Docklands (now in Melbourne).

The worst of the overcrowding is in the outer-suburban electorates north and west of the Yarra (all Labor), while the most undersized electorates are in the south and east (mostly Liberal). On the population assumptions I used, the ideal redistribution would put 12.5 seats in the northwest (up from 11 now) and 16.5 in the southeast (including the urban/rural fringe seat of McMillan). That could be done by having one seat straddling the Yarra — Casey, Menzies or Jagajaga in the outer area, Melbourne or Melbourne Ports in the inner one — or by a combination of both.

One option is for the commission to retain all thirty-seven existing seats, making the changes needed to roughly even out their future enrolments, and simply add the new seat northwest of the Yarra. The other is to bite the bullet and abolish an undersized electorate in the southeastern suburbs — one of Deakin, Chisholm, Bruce, Aston or Hotham — to put two extra electorates in the northwest. The direction of Melbourne’s growth suggests that will be inevitable next time, if not now.

My own suggestion was to keep all existing electorates, bring Melbourne Ports across the Yarra to take in the port of Melbourne and surrounding areas such as Docklands, and move Menzies across the Yarra in the outer northeast. That has the double benefit of allowing the commissioners to scrap the gerrymander that added suburban Caulfield and East St Kilda to Melbourne Ports, and put them in Goldstein and Higgins, where they belong. But whatever choices the commission makes, and there may be better suggestions than mine, they will certainly redraw the boundaries of those inner-suburban electorates.

The two major parties have been no help. Their suggestions are self-indulgent exercises in the art of the gerrymander, and will be ignored. Both want to keep Melbourne Ports as it is. Labor proposes making Casey straddle the Yarra on Melbourne’s outer fringe; the Liberals don’t even acknowledge the problem. And Labor wants a gerrymander that would group as many Greens-voting suburbs as possible in Melbourne, to get them out of Batman and Wills.

The Greens’ suggestions are also self-interested, but at least more plausible. They propose shearing off Labor-voting suburbs from all four seats: Ascot Vale from Melbourne (for its own reasons, Labor concurs), Glenroy from Wills, parts of Bundoora from Batman, and Caulfield from Melbourne Ports. They want to see both Casey and Melbourne Ports cross the Yarra.

It’s interesting that the names of the seats appear to be a bigger issue than their boundaries. Labor and the Greens, among others, want to expunge the names of Batman and McMillan, both names associated with violent removal of Aborigines from the land, and rename their electorates with Aboriginal names. The Liberals made no comment. My own suggestion was to go back to naming electorates after places, not people, so we all know where they are.

Bottom line: it is inevitable that the boundaries of Melbourne’s inner-suburban seats will be redrawn. But it will be next July before we know how.

Fortunately, we won’t have to wait that long for the outcome in Queensland. Most of the questions are about One Nation, not the Greens. But a Galaxy poll last week for the Courier-Mail found deputy premier Jackie Trad trailing Greens thirty-year-old Amy McMahon in South Brisbane by 49 per cent to 51, despite the Liberal National Party preferencing Labor.

The Greens made only minor inroads in the Western Australian election, will barely get airplay in South Australia, and are yet to recover from their losses in Tasmania. Are they becoming essentially the party of inner Melbourne? The Queensland election is an important test for them too. ●