There’s a federal by-election on the way in Eden-Monaro, the NSW electorate whose post-1969 bellwether status was abruptly terminated by a Labor victory in 2016 (and again in 2019).

Flattening the attendance curve will be a challenge for the Australian Electoral Commission. Extra postal and pre-poll voting might be on the cards.

Retiring MP Mike Kelly has tried to put a positive spin on the timing. Eden-Monaro will benefit, he says, from being in the spotlight for the weeks or months until the poll. But the whole thing will be a headache for his leader, Anthony Albanese, for one simple reason: the Coalition has a very good chance of taking this seat.

Let’s be clear: by-election results tell us three-fifths of five-eighths of bugger-all about a party’s competitiveness at the next election. On the contrary, the very fact that who will govern is not up for grabs frees people to vote with other motivations in mind. Very often they end up giving an arrogant government a kick in the shins.

But by-elections are invested with all sorts of powers by the political class in this country. Remember Canning in 2015? Prime minister Tony Abbott was getting the wobbles and the by-election was declared a test of his leadership. If the swing to Labor was greater than 11.81 per cent (the margin it was held by), Tony was finished. If it was greater than 5 or 6 it might be touch and go. Everyone had an opinion. Then the cart overtook the horse and the story became “we might lose Canning!” (as if that much mattered for a party with a thirty-seat majority). So we’d better make the leadership change now to save the seat! Which they did.

Or recall when, just two years ago, five electorates were voted on in a single day in July. One of them, Longman, produced a modest 3.7 per cent two-party swing to Labor (off a 9.4 per cent primary swing to One Nation, which pretty much came off the LNP primary vote) and ended up triggering Malcolm Turnbull’s demise. It too was crazy. But that’s Australian politics.

Any discussion of Eden-Monaro needs to acknowledge the enormous popularity of Mike Kelly. He held it from 2007 to 2013, lost to Peter Hendy in that big Coalition victory, and took it back in Labor’s better-than-expected 2016 showing. Unlike most candidates, he was a known, popular quantity in 2016. Voters tend to like uniforms — former coppers or soldiers — in candidates anyway, and they particularly like and liked him.

There were accounts that Hendy was a poor local member, but that might just be after-the-fact rationalisation. Unlike many new MPs, the dour economist was not given a “nodding position” in parliament behind the prime minister. (To me, the idea that locals punished him for his part in Abbott’s removal is very far-fetched.)

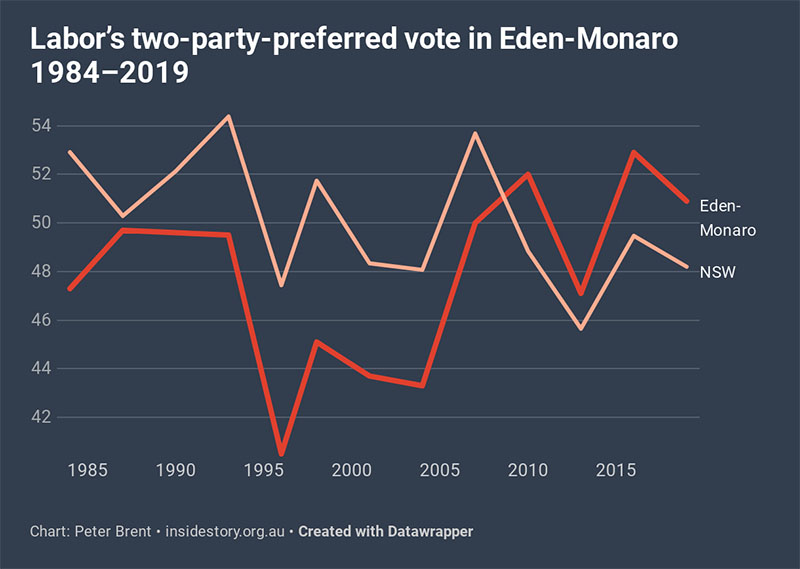

How do we know Kelly has a high personal vote? We get an idea from this graph, which shows Labor’s two-party-preferred vote in Eden-Monaro and New South Wales as a whole over the past thirty-five years.

The graph is adjusted for redistributions — and the first thing it shows us is how these have benefited the Coalition in recent years. Kelly didn’t really get 50 per cent in 2007; he received 53.4 per cent, but since then boundary changes are estimated to have made his job harder by an accumulated 3.4 per cent. Kelly’s personal vote has masked that — although it’s also possible that, net of redistributions, demographic changes have made the electorate more Labor-inclined.

But on today’s boundaries he received an estimated 50 per cent when Labor’s state vote was 53.7, a deficit of 3.7. Last year his vote was 2.6 per cent higher than the state one, a change of 6.3 per cent.

Notice how the Eden-Monaro line was always below the state one until 2010, and since then always above. (Labor actually held it under the Hawke and Keating governments, but on these estimates would not have on current boundaries.) We don’t know if Labor would have won Eden-Monaro in 2016 with a generic candidate, but we can be certain that Kelly made the difference in 2019, when he hung on by 0.85 per cent.

Kelly also does very well when judged by the difference between a candidate’s vote in the House and his or her party’s vote in the Senate.

The by-election result will depend on many things. What the electorate is thinking of the government at the time of the contest will be a big factor that we simply can’t judge at this stage. We are in strange times. Candidates will matter, perhaps a lot; they matter more at by-elections than general ones. A strong Liberal candidate would stand an excellent chance. Jim Molan has some wacky ideas, but if he can remain disciplined he’d be a strong contender. He’s another ex-soldier, and a very senior one at that. And the other person being talked about, state Liberal minister Andrew Constance, would be even better, because he generated enormous goodwill over the summer fires.

Eden-Monaro is no longer a bellwether, and it’s actually more a natural Coalition seat than it used to be. So the Coalition has a good chance of taking it. In fact, I think (factoring in the likelihood of a strong candidate) it probably will.

The result, whatever it is, won’t tell us anything about the next election. But it will be widely interpreted as if does. Especially, in the event of a loss, by Albo’s enemies. •