As this extended election campaign nears its (possibly merciful) end, there is a commentariat consensus that Labor, while making some gains, will fall short of a win. The magnitude of the gains will, of course, play a critical role in the futures of both major-party leaders. Complicating the picture is the likely size of any crossbench, which could range anywhere from three members to ten, with the Xenophon factor in South Australia a key unknown.

The question mark over the crossbench also serves to highlight the limitations of the opinion pollsters’ concept of the two-party-preferred vote. This tool works best in a setting where Labor and the Coalition win all 150 seats between them; it is less useful when the waters are muddied by Greens and independents. A two-party-preferred vote of just over 50 per cent is less likely to deliver a lower house majority if there are ten or so crossbenchers in the chamber.

Notionally allocating Clive Palmer’s seat of Fairfax back to the Coalition, we are left with a “current” crossbench comprising two seats historically held by Labor (Denison and Melbourne) and two historically by the Coalition (Kennedy and Indi). In the event of a close contest, the Coalition would not want additions to the crossbench to come exclusively from their side, via the loss of New England to independent Tony Windsor, for instance, and Mayo to the Xenophon Party.

If Labor does fall short of the necessary swing, explanations can start with that most durable of excuses, the historical record. No first-term federal government since 1931 has lost office – and in that case it took a major economic depression. Whatever the current state of the economy, we are not in a depression.

Some political observers have viewed this pattern as a minor obstacle, citing the recent fall of one-term state governments in Victoria and Queensland. The comparison has always been flawed. The election of Victoria’s Coalition government in 2010 was as close to an accident as is possible in electoral politics, and it fell into effective minority government status in the second half of its term. This left premier Denis Napthine with no margin for error, and effectively doomed his government. The Queensland case was different, but Campbell Newman (unrestrained by an upper house) governed with an arrogance and political ineptitude that even Tony Abbott could not have matched. And, of course, it is far more difficult to secure a large swing across six states of a federation than it is in a single state, even one as large and diverse as Queensland.

Another factor is also at play. State government is essentially about service provision (a perceived Labor strength) while federal government is essentially about economic management (a perceived Labor weakness). The Victorian and Queensland results are consistent with that differentiation.

The federal campaign has highlighted the enduring difficulties that Labor faces on the key issue of economic management. While polls show that the party is preferred by voters on health and hospitals, education and the environment, the Coalition is preferred on the economy by a two-to-one margin. Astonishingly, the same is true on interest rates, despite the low levels maintained under the Rudd and Gillard governments. This speaks in part to a failure of communication or, as Peter Brent has put it, a vain hope in Labor ranks that if it hammers on about “fairness,” concern about economic management will go away.

Ominously for Labor, polls reveal a heightened concern about economic management in marginal electorates, a significant barrier to securing the necessary swings in those key seats. If Labor can win government with this handicap, the rules of the game will certainly have changed.

The British vote to exit the European Union can’t have helped Labor, with any hint of financial instability playing to the strength of the incumbents. There is a faint echo of the 1963 federal election, when US president John F. Kennedy was assassinated a week before polling day. The tragedy helped validate the Menzies government’s case for re-election in an unstable world.

Several poor-quality preselection decisions were exposed during the campaign and it will be interesting to see whether this proves costly in the seats concerned (as it did for the Liberals in Greenway in 2013) or whether national issues prove more important in local voting. The ubiquity of social media now means that indiscreet and imprudent comments that in the past may have been picked up only by one’s fellow drunks in the pub are now out there for all to see. While some slack may be cut for those whose gaffes might be filed under “youthful indiscretions,” several problematic comments turned out to have been made in quite recent times.

This trend does suggest that parties are still undertaking inadequate due diligence when they select candidates, and this needs to be sorted out, at least in winnable seats. It may also indicate that major party preselections are based more on ideological intensity (in the case of the Liberals) or the factional merry-go-round (in the case of Labor). Merit and a trouble-free social media history seem to have been of no great concern.

At state level, the Victorian government’s politically inept handling of the proposed changes in the union/volunteer firefighters’ relationship leaves open the possibility of voters in affected areas opting to punish federal Labor. The seat of McEwen is intriguing in that context: it is vulnerable for the sitting Labor member on the firefighters issue, but the Liberals are disadvantaged by their less than brilliant choice of candidate.

Questions arise as to why premier Daniel Andrews chose not to defer decision-making on this politically tricky issue until after 2 July. In the event that it does prove electorally costly, federal colleagues may be especially keen for some explanation.

The impact of one development late in the campaign can be confidently assessed. Paul Keating’s robust attack on the Greens, supporting Anthony Albanese in his vulnerable seat of Grayndler, no doubt played well to the Labor tribalists but is unlikely to have moved any votes from the Greens to the ALP. Abuse has a fairly poor record as a change agent, even when laced with the picturesque language of the former prime minister.

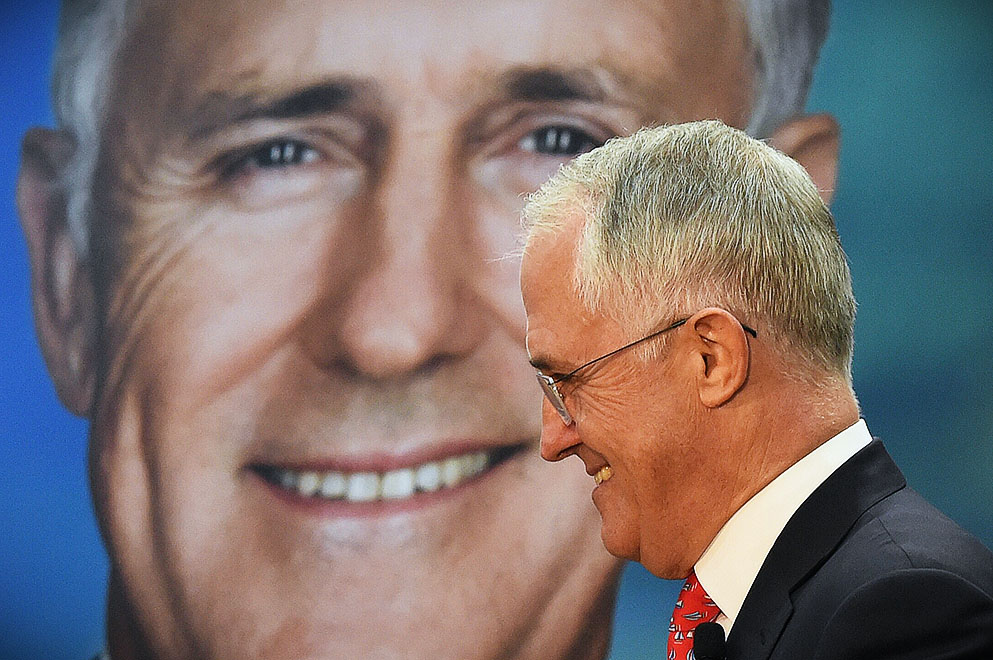

Keating’s attack included criticism of the Greens for blocking Labor’s access to potential majority government. It was left unclear why a party that routinely polls less than 40 per cent of the national vote should enjoy some god-given right to majority government. But then again, democratic principles have rarely featured prominently in the syllabus of the New South Wales Labor right. It is curious that major party figures (including Malcolm Turnbull) who regularly extol the virtues of diversity seem unable to accept the diminishing appeal of a two-party system that can’t reflect that diversity.

Critically, the economic debate has not seemed to be going Labor’s way in the last week of the campaign. Polling conducted a week before the election has suggested two-party-preferred support at 51–49 in favour of the Coalition, an outcome predictably promoted by the media as suggestive of a “close” election. While 51–49 might be a close result in a sporting contest, it need not be so in an election for 150 single-member constituencies. Indeed, in a worst-case scenario, a two-party-preferred vote of around 49 per cent could limit Labor to a mere handful of gains and result in Bill Shorten’s main problem after 2 July being the question of whether to serve in his successor’s shadow cabinet. •