The Murdoch empire has never successfully completed the transition from feudalism to capitalism. And Rupert Murdoch, despite having ostensibly stepped back in recent years, obviously wants to keep it that way.

The elderly mogul’s dynastic ambitions were on spectacular display last week when the New York Times revealed he was seeking to alter the “irrevocable” voting rules of the Murdoch Family Trust. This move not only surprised media-watchers around the world but also shocked the three people most affected — his children Prudence, Elisabeth and James. It showed yet again that Rupert wants to control his business from beyond the grave, and points to much sharper faultlines inside the family than previously thought.

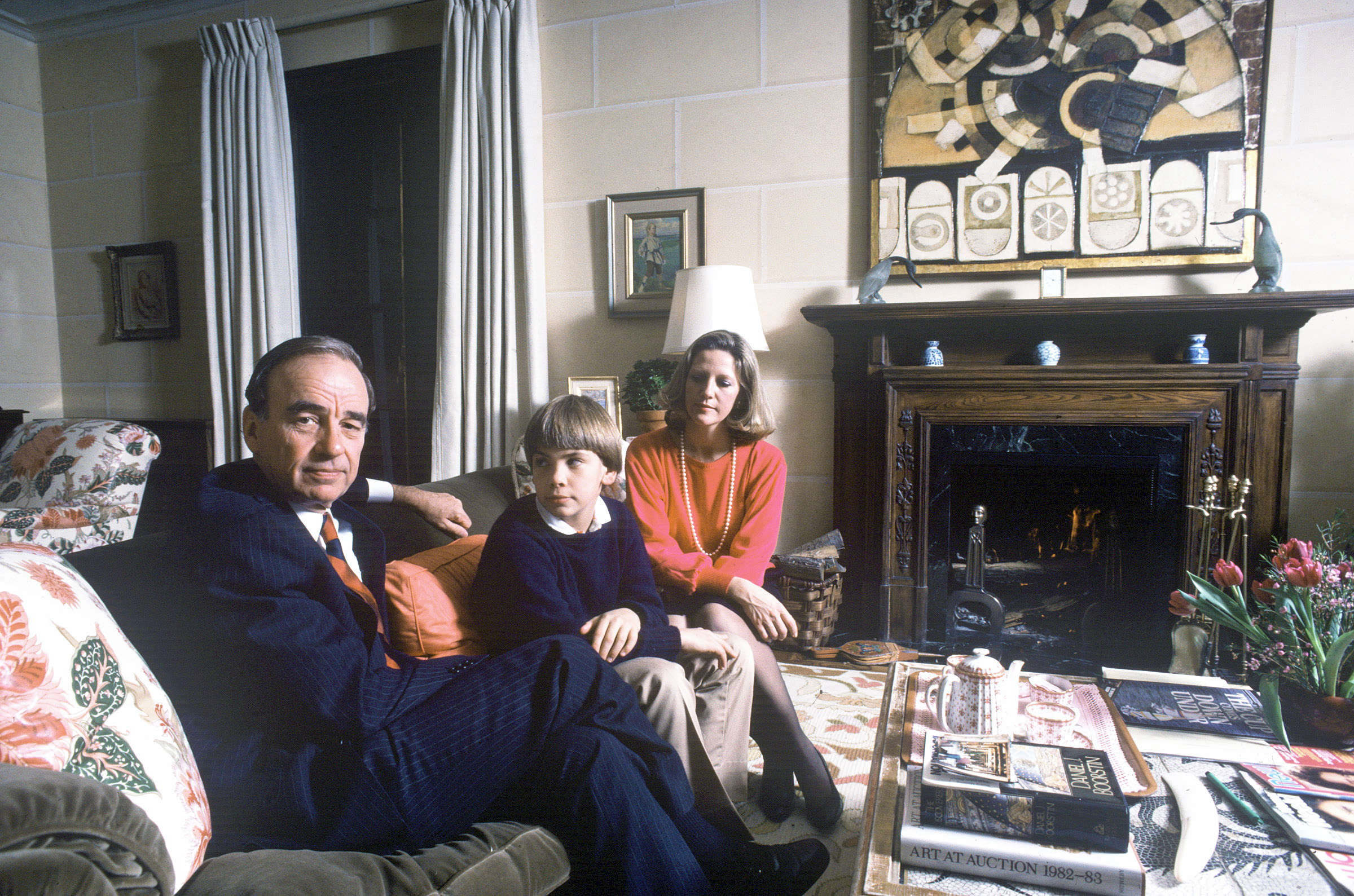

Last November, as the Times revealed, Rupert initiated legal action to change the rules governing the trust, which holds the Murdoch family’s share of Disney, Fox and News Corps shares. Drawn up in 1999 during his divorce from Anna, it was his estranged wife’s attempt to guarantee the inheritance of her three children, Elisabeth, Lachlan and James, along with that of Prudence, Rupert’s only child from his first marriage. Its aim was to protect the four offspring from any future actions by his new wife, Wendi Deng. Later, Rupert’s children with Wendi (Grace and Chloe) were added as financial beneficiaries but without voting rights.

The Trust currently gives each of the four children one vote and Rupert four, together with a guarantee he can never be outvoted. After his death each of the four children will have an equal say.

The Times’s great revelation was that Rupert is attempting to put his chosen successor, Lachlan, beyond any challenge from the other three. His justification is that the viability of the company rests on its right-wing appeal and the other three would dilute or endanger that appeal.

It is an unusual, probably unique, legal argument. It requires a judge to rule on the contrasting commercial benefits of different editorial stances and formulas. Most of the attention will be on Murdoch’s Fox News, but the empire also includes newspapers in Britain and Australia as well as the United States. It is asking a lot of a judge in Nevada to decide whether greater editorial integrity and pluralism would help or damage the profitability of the New York Post, the London Sun and the Australian.

The Trust can only be altered if all its beneficiaries would benefit. With the other three children contesting the move, Rupert must convince the judge that three adults of healthy mind and body don’t know what is best for them and their wishes should therefore be overridden.

My guess is that he will fail.

The key conflict Rupert is trying to neutralise is between Lachlan and James, who reportedly have not spoken for five years. To the extent that the conflict stems from political differences, James appeared for a long time to be the greater villain. In order to advance News Corp interests in China he was an apologist for Beijing; he claimed that the BBC’s power was a threat to democracy; he equated anyone who believed in media regulation with creationists; he oversaw the company’s British operations while the News of the World was energetically phone-hacking and told several lies in his own and the company’s defence. And he did all of this with a maximum degree of abrasiveness.

Now, though, he is the good guy. One turning point came when, after 2017’s notorious neo-Nazi rally in the US city of Charlotteville, Donald Trump declared there were some very fine people on both sides. James was appalled at how Fox News played down the remark. “There are no good Nazis. Or Klansmen, or terrorists,” he said in a statement, and donated a million dollars to the Anti-Defamation League.

James and his wife Kathryn also feel strongly about the challenges of global warming and find the Murdoch media’s coverage of the issue infuriating. And they believe Fox News should have taken a stronger stance against Trump’s abuses of democratic processes. These views put James on the outer with his father and older brother.

While the conflict between Lachlan and James is intense and probably irreconcilable, Elisabeth’s and Prudence’s views have been less clear. But thanks to Rupert’s initiative any fluidity will now almost certainly solidify into opposition to Lachlan. Even at a personal level he is now clearly estranged from these three offspring, none of whom attended his wedding in June.

Apart from his conservatism and willingness to preserve the right-wing appeal of the editorial products, what leadership credentials has Lachlan displayed? Michael Wolff, who had more access to the Murdoch camp than any other biographer for his 2008 book The Man Who Owns the News, and whose contacts have clearly continued, had no time for Lachlan or James. For Wolff, relations with the sons “was a shadow that hung over Murdoch’s entire management team. It engaged the time and the futures of every key executive: how to handle, accommodate, and survive Murdoch’s detested children.”

In the same vein, Wolff says that “there were no illusions about Lachlan’s general business muddle, indecisiveness, and dependence on his father’s views; nor was there any rosy way to mask James’s temper, in-your-face certainties, and inability to play nicely with others.”

According to Wolff, Lachlan was only a part-time presence at Murdoch HQ. Fox News’s star host, Tucker Carlson, who was reputedly very friendly with him, “was more than a trifle concerned that his boss — and protector — was spending most of his time continents away, as well as underwater, instead of on the job.”

Fox News’s biggest crisis in recent years has been the successful defamation action by Dominion Voting Systems, the computer system widely used in US elections. Having broadcast many stories baselessly claiming the company was involved in an anti-Trump manipulation of votes, Fox News was forced to settle for one of the biggest defamation payouts in history, US$787.5 million.

The defeat was not only very expensive, it was also deeply embarrassing. The discovery process showed just how dishonest key executives and journalists had been, highlighting the huge gap about what they privately believed and what they put to air.

Fox News’s response — led by Viet Dinh, a Lachlan appointee and friend — was clumsy, and for a long time clearly underestimated the size of the threat. Months in, a nonchalant Dinh said the action was not on his list of top twenty worries. Soon after the record settlement, Dinh left the company. Looking back on this catastrophe, and examining the depositions and internal communications, it is hard to see any single act of leadership that Lachlan undertook.

The issue is not simply the skills of Lachlan or James; it is the impact of a hereditary elite on other senior staff. In 2011, at the height of the phone-hacking scandal, Rupert declared that the News of the World accounted for just 1 per cent of a global business with a total of 53,000 employees. Since the profitable sale of many assets to Disney in 2019 and other cutbacks, staff numbers would have fallen by more than half. The idea that not one of those tens of thousands of people is best to run the show — that the job should instead come as a birthright — is at least a century out of date.

Talented managers who did much to improve the company’s performance — beginning with Bill Diller, the primary builder of the Fox TV network in the 1980s, who wanted a share of ownership that Murdoch refused to give up — left because no matter how well they performed they faced an impenetrable ceiling.

That ceiling only exists because of Rupert’s iron grip. Decades ago, when he needed to raise capital but didn’t want to dilute control, he engineered an issue of non-voting shares. Such shares are against the spirit of the sharemarket, where governance should align with ownership, but they are not uncommon. Those who bought the non-voting shares in the Murdoch empire did so with their eyes open, seemingly happy to see its patriarch exercise control.

The result is that the Murdochs control around 40 per cent of the voting stock in the two main Murdoch companies, News Corp and Fox Corporation, but own only around 20 per cent of the total stock. On several occasions shareholders have attempted to abolish this dual-share structure, but so far they have not gained majority support. If an attempt were to succeed, the Murdochs’ control would be halved.

Shareholders are showing signs of becoming more active. When Rupert and Lachlan moved to re-merge the two companies in October 2022 they met strong resistance, and abandoned the effort the following January.

Rupert has the prestige of the company founder, the leader who built the empire. His successor will not have that aura. With management facing significant challenges in both companies, shareholders are likely to become increasingly impatient.

The focus of attention since the Times disclosures has very much been on the Succession-like family drama and the counterproductive overreach of a nonagenarian. But that focus may be too narrow. We may also be seeing the first signs that this multinational corporation’s time as a family company is coming to an end. •