Head On Portrait Prize 2015

Museum of Sydney until 8 June 2015

In almost every field of creativity – from literature or journalism to art or cooking – the line between the professional and the amateur is becoming harder and harder to spot. Nowhere is this more so than in photography, where the ubiquity of the practice itself and the images produced – the fact that almost everybody is a photographer now, just as everybody is a consumer of photographs – constitutes the prevailing landscape. Yet the status of photography as an art form is also being loudly asserted.

The result is that photography seems almost to exist in two parallel universes. In one, we are being overloaded with images to the point that it is all becoming a bit of a blur, and we find it difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish one image from another. In the other, photography is being talked up as an ever more collectible art form, a sure bet for the astute investor. The inaugural photography fair Photo London, for instance, which was launched in May this year as a declared rival to Paris Photo and the Los Angeles Photographic Art Exposition, aims to open up new audiences, showcase new talent “and promote the concept of photography as an asset class.”

These “new” audiences must be drawn from the existing one, of course, to which we all belong – an audience practised at taking in images at a glance, perhaps making a judgement or perhaps not, and then moving on. We have grown accustomed to seeing photographs as a stream rather than in an album or hanging, painting-like, on a wall. The slide show of the olden days, which might have taken up a whole evening of quiet (and growing) desperation, now rushes by in a matter of moments. The arrow on the right hand side of the screen warns against lingering to award any single photograph primacy over the others. Accompanying these new ways of making photos (smart phones always at the ready) and looking at them, often referred to as the medium’s “democratisation,” is a certain democratic impatience with the idea of the “name” photographer and the iconic photograph – exactly the kind of photographer and photograph that slots comfortably into the asset class.

Something of this increasing disjunction between art photography and vernacular photography can be seen in an exchange between two of the best and best-known writers on the subject of photography, Janet Malcolm and Geoff Dyer, in a recent issue of Aperture magazine. During their back-and-forth of comments on the state of the medium, it becomes increasingly clear that they are approaching the subject from quite different angles. The conversation eventually turns to a major retrospective of the work of influential street photographer Garry Winogrand, whom Dyer greatly admires and Malcolm, it transpires, does not. In being awarded the accolade of a touring exhibition on sequential display in five of the world’s major venues – including the Met in New York and the Jeu de Paume in Paris – Winogrand seems in no danger of losing his star status, democracy or no democracy.

And yet, says Malcolm, exaggerating no doubt for emphasis, “I have to confess that over the years, I have changed my mind about Winogrand’s photographs,” to the point where she now finds them “consistently and uniformly uninteresting” and difficult to distinguish from “any snapshot.” In expressing her scepticism, Malcolm catches a mood, the same mood that is reflected in the current revival of interest in “found” and archival photography – all those snapshots and family photos that have somehow become detached from their families to survive without history or much in the way of identifying notes, including any record of who actually took them in the first place.

On these questions, the 2015 Head On Portrait Prize, currently on show at the Museum of Sydney, manages to have a bet each way. Since its inception in 2004, the competition has specified that all entrants will be judged anonymously – that the names and details of the entrants won’t be available to the judges until the conclusion of the judging process. This must be treated as more of a statement of intent than a guarantee; after all, photographers have their signature styles. And besides, many of the submitted images will inevitably have appeared elsewhere, online or in exhibitions, or in some cases in earlier photo competitions. Yet the highlighting of anonymity in the selection process has a way of setting the mood and extending itself to the photographers’ choice of subjects, who are typically “unknown” in the sense that they are not the kinds of people already visible enough to bring with them the trappings of other images we may already have seen.

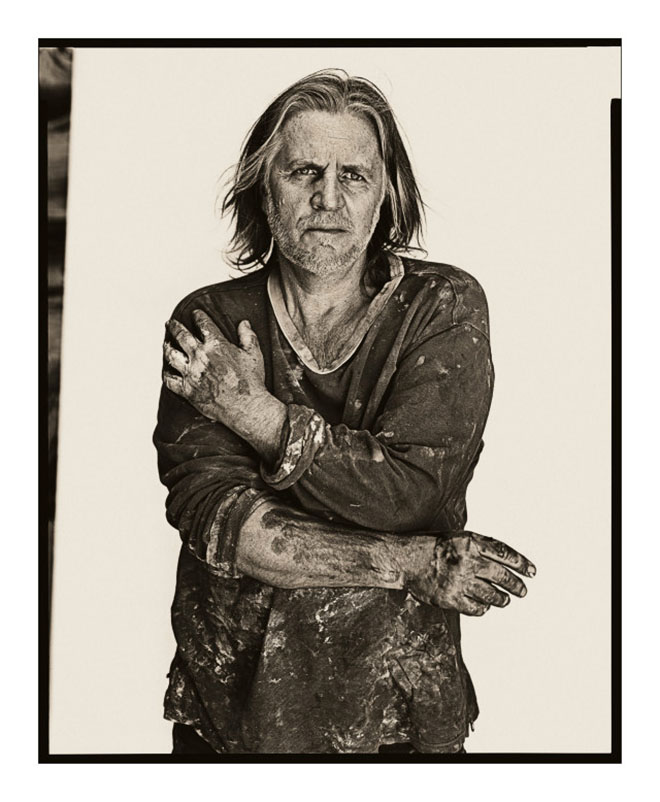

This turns out to be quite important. Where photographic portraiture is concerned, it can be very different looking at an image of a celebrity taken by a star photographer and at an image of someone we don’t know taken by someone we haven’t heard of – when, in other words, we have minimal information on what Geoff Dyer refers to, in that exchange with Janet Malcolm, as “the old who by/what of.” Among the forty photographs selected as finalists in this year’s competition, the subjects of only a handful could be described as well-known figures – an image by Paul Green of Madam Lash, for example, looking like a racier version of the robot woman in Metropolis, and George Fetting’s strong, straightforward portrait of the artist and photographer George Gittoes (below).

Fetting has made something of a specialty of celebrity photography, sometimes producing images in which the subject seems to have been given too much leeway to pose in a way that suggests a contrived sense of fun or daring or difference. But here the pose works – Gittoes’s arms are held awkwardly and protectively across his chest and torso, suggesting a vulnerability that is belied by the strength of his expression and the directness of his gaze. That strength is emphasised by Fetting’s decision to place his subject against a blank canvas, unencumbered by quirky props or anything that might divert the viewer’s attention.

One of the great challenges facing any portrait photographer is whether to use props and, if the decision is yes, what form they might take. Hats have been relied on since the very beginnings of portrait photography, or indeed of portraiture generally, but even so, what are the odds against two of the forty finalists in this year’s exhibition choosing to capture their subjects wearing hats and veils of the kind favoured by beekeepers? (A third such image, Beekeeper 1 by Neil Bailey, is included in a slide show of commended entries that didn’t quite make the final cut, and is part of an appealing series of Bailey’s showing beekeepers in full regalia posed to resemble space explorers.)

In Craig Proudford’s Rolf (below) we see the subject, “a retirement-home resident in Sydney,” wearing the trademark headgear of his hobby, posed casually and self-effacingly with his hands in his pockets, in a mauve polo shirt and crumpled trousers. Rather in the manner of Fetting’s Gittoes, Rolf is relatively prop-free compared with others of Proudford’s portraits viewable online. Rolf is posed well back in the depth of field, surrounded by a plain grey floor and plain cream walls that suggest an institutional setting. The hat and veil seem to add to the understated warmth of the portrait, emphasising rather than obscuring the personality of the subject.

The veil works in a similar way in Matthew Abbott’s double portrait of John and Julie (below), taken in Lightning Ridge, in which he succeeds in making his subjects seem both comic and sympathetic. “It took me three days to convince John and Julie to allow me to take their portrait,” explains Abbott in the wall notes. “I was drawn to their unique solution of wearing mosquito nets as headdresses to combat the relentless flies.” Abbott has tended to concentrate on photojournalism and documentary photography, winning favourable attention for a series taken in Arnhem Land, which led to a Sydney Morning Herald scholarship as an emerging documentary photographer in 2013. The Arnhem Land sequence required considerable patience – it was a year, by Abbott’s own account, before he felt sufficiently established there to begin photographing the people and the landscape. These attributes of patience and persistence serve him well in John and Julie – there is a quality of complicity in John and Julie’s expressions, with each other and with the photographer, that seems to make them partners in the enterprise rather than merely subjects.

A number of the common tropes of contemporary portrait photography appear in this exhibition, some more than once – subjects photographed in the pose and attire of classic paintings, or shown with their faces and features either partially or completely submerged in water, or obscured by a splayed hand held in front, or illuminated by rays of light filtering through branches and leaves. Each has assumed the status of a convention – making it difficult to play successfully on the convention and to reanimate it. Eva Christina Schroeder’s rendering of Girl with a Pearl Earring, entitled Girl in a Plastic Bag 1, is one of many such homages to Vermeer’s painting made in recent years, instances of which can be seen in Awol Erizku’s photograph of the Girl with a Bamboo Earring or in the ambitious series by Dutch photographer Hendrik Kerstens. Schroeder’s version only half succeeds – the black and white image of her daughter wearing a plastic bag as a headscarf doesn’t quite convince as an ecological statement about “the current trend to recycle.” But for all that, the young girl’s contemporariness and individuality are more than a match for the constraints of the costume.

In another re-creation of a classic painting, Ben Scott’s Girl at the Bar, a kitsch and clever reworking of Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergères, the aesthetics of advertising are proudly displayed; the image stands out as the only one among the forty finalists to openly glamorise its subject. The second place-getter in the competition, student of photography Glyn Patrick, also confidently reworks photographic convention – in her case the use of light filtered through trees to illuminate the subject – in her portrait of John, who has recently undergone facial surgery and who consequently “turns his back on the sun he loves.” Despite the fact that he is facing away from it, the image links the subject to the natural world. In fact, John seems to be standing in a kind of illuminated crop circle, lending the image an otherworldly quality and an aura of serenity.

Patrick takes a sympathetic, even protective approach in JOHN (shown at the top of this page). Others among the finalists are more interested in exposing imperfections and searching out vulnerabilities in an attempt to identify the essential humanity of the subject. None more so than the winner of the first prize in the competition, Molly Harris, with her portrait, Being Sandra (below). This initial photograph in a projected series shows Sandra, formerly John, a veteran of thirty-seven years in the Air Force, as she prepares in front of the bathroom mirror prior to leaving home to attend an Anzac Day commemoration. We are given something of Sandra’s background and perilous state of health in the wall notes, but in some ways these notes are superfluous.

This photograph’s capacity to convey both vulnerability and an uncertain future comes in large part from its confident handling of light, a light that seems here to derive entirely from the bathroom cabinet, creating a powerful and unsettling mood even as it fights an unequal battle against the gloom. Other portraits by Harris, who has already received significant recognition in her short photographic career, are viewable on her website, and show a similarly sophisticated way with light and its capacity to engender atmosphere and suggest complexity of character.

One of the great mysteries of portrait photography hinges on whether we can successfully read character and biography into a single image. Or perhaps the more important question is whether we believe that we can. It is partly a case of the right subject taken at the right moment and in the right light by the right photographer. But it is also the case that photography favours the old, in the sense that personality and character seem to be more discernible in the lines and infirmities of age, if only on the grounds that lines and wrinkles betoken experience, and experience, by one definition at least, is character.

It is more complicated with photographs of children. When we look at childhood photographs from the past we sometimes know what happened next – what happened when the child grew up – but more often we do not. And in the case of contemporary childhood portraits, such as the ones included in this exhibition, it is in the nature of things that we can’t know the rest of the story – character and personality, in their fully formed state, lie in the child’s future and also in ours.

Samantha Everton, in Sawat (above), from her Sang Tong series, which has been awarded third place in the competition, alludes to the formation of biography and character in her carefully staged photograph of a young child who, we are told in the wall notes, has been adopted from Thailand into an Australian family. In this and other images from the series, Everton takes as her theme

children who live in two worlds. They identify themselves as Thai but they’re also everyday Aussie kids. I wanted to show both the harmony and the tension between their dual realities.

The elaborate and sophisticated way in which this photograph has been designed, with its careful and precise use of colour and pattern, and with the child suspended dream-like among familiar or beloved objects, renders it both child-like and grown up, which may well be true of all the best photographs of childhood.

And so the Head On Portrait competition begins in anonymity and ends by naming a small number of photographers who could one day become – or may already, like Everton, be well on the way to becoming – “names.” It is one of the many such competitions, in Australia and internationally, that attract thousands of entries. Which shows that the democratisation of photography does not necessarily mean its standardisation. It just means that there are many more photographs, and many more photographers, to choose from. •