When the second world war began, Max Dupain and photographer Olive Cotton had been married for five months and he was thriving personally and professionally. Around him he had his loving, supportive family and a wonderfully creative and encouraging group of friends and colleagues. His professional position was exceptionally strong: in the five years since he had established his own business, he had been recognised as a leading modernist photographer in both the professional and art spheres.

By the time the war was over, he had endured massive disruptions that left no aspect of his life untouched. He was divorced from Olive and had married Diana; he had seen his family only intermittently; friends including the photographer and cameraman Damien Parer, his school rowing partner Clarence Glasscock, and Gil Dawe, a pilot with whom he had trained at Bankstown, had been killed.

He had spent years separated from other friends, such as Douglas Annand, Richard Beck and Ernest Hyde, who, like Dupain, were not based in Australia for the duration of the war. Other friends were dispersed across the globe. His friend Jean Lorraine had married an American paratrooper, William Bailey, and later settled in the United States, where she became a journalist and champion of women’s rights. Dupain had also been away from his business since 1942 and had lost the vital connection with it.

Everything had either changed or shifted in significance, a feeling to which photographer Harold Cazneaux, a generation older than Dupain, gave voice in 1947. Having experienced the tragic death of his only son, Harold junior, at the Siege of Tobruk in North Africa in 1941, and of his son-in-law, Hugh Johnson, who was killed when the HMAS Hobart was hit by a Japanese torpedo in 1943, he suggested with dignity and sorrow that “all were plunged into the turmoil of the Second Great War, and now in its passing we are all struggling to re-establish the things that are worth living for. This will be no easy task.”

Dupain was in complete agreement, writing that “the war in Europe overwhelmed all and it was not until the mid-forties that we could even think straight again.” Decades later he candidly acknowledged how hard it was to settle down after such “a gigantic upheaval,” elaborating on this situation in his book Max Dupain’s Australia in language that is direct, almost confessional:

The unstable war years, the grudging adaptation to ever-changing surroundings, the thousands of impressions both good and bad of varying environments, all added up to long-term shock. I just needed a settled emotional life for a while in order to get my life and work into a new perspective.

Nonetheless the task from September 1945 onwards was clear — to return to the studio and resume a civilised life, which Dupain knew would require his full conscious effort.

Dupain’s library contained volumes of D.H. Lawrence’s poetry, but because its contents were never fully documented, it is not known exactly what he owned. It is very likely, however, that he was familiar with Lawrence’s poem “Phoenix” (1929). Lawrence wanted the phoenix as the heraldic emblem for the free community he hoped to establish, and his biographer Frances Wilson has suggested that the emblem of the phoenix rising came to represent Lawrence himself. The poem begins with a powerful rhetorical question that was bound to have captured Dupain’s attention:

Are you willing to be sponged out, erased, cancelled, made nothing?

Are you willing to be made nothing?

dipped into oblivion?

If not, you will never really change.

There is no question that Dupain wanted his wartime experiences and fraught emotional state to count for something, and phoenix-like he was determined to be reborn. This required active reinvention in his three worlds: in his personal life — represented in his marriage to Diana — and in both his professional and creative work as a photographer.

First, however, he had to honour Parer and his legacy. In 1946 Dupain published “A Note on Damien Parer” in the first issue of his friend Laurence Le Guay’s bold new venture, Contemporary Photography magazine. (Le Guay had only recently returned to Sydney after serving as a photographer with the RAAF.) Dupain’s tribute was infused with his intimate knowledge of a man he summed up as “unassuming and sensitive.” He noted how inspired Parer was by his first forays into the film industry, an experience that “had put a dash of elixir into his being. His voice was louder as it hollered out his latest favourite poem ([Hilaire] Belloc or [G.K.] Chesterton preferably) from the dark precincts of the laboratory while, detached and mechanical, he rocked a tray full of films or prints.” With pride Dupain recalled the alteration in tone in Damien’s letters from the Middle East as he became more confident about his work and his capabilities, and he stressed Parer’s deep involvement in the documentary movement, which grew out of his work in film in the late 1930s.

The postwar development of Dupain’s approach to photography had several components that he had formulated while serving as a camoufleur. He announced them publicly in a flurry of publications that reappeared after the war, notably in his contributions to Contemporary Photography and Australian Photography, edited by Oswald L. Ziegler and conceived as an annual (both 1947), and Art and Design: A Ure Smith Publication, edited by Sydney Ure Smith and Professor Joseph Burke (1949).

These articles amounted to a series of provocations and rallying calls. In Contemporary Photography, for example, he made a spirited address to his fellow photographers who, like him, were attempting to settle down to business again.

It’s back to the yakka now, boys! The studio grind again, but with a fresh outlook, new ideas and possibilities. I want to use more sunlight in my work. The studio has an odd flavor about it now and the artificial quality of half-watt lighting does not ring true alongside sunlight. We have it here all the year round — so why not make use of it! Maybe it is just a habit I have got into after four years of Rolleiflex and sunshine.

The point is that photography is at its best when it shows a thing clearly and simply. To fake is in bad taste. The studio is synonymous with fake.

This passage marks Dupain’s conscious break with his prewar work and a commitment to a new philosophical position and new way of working. The crux is realism, which was paralleled in other areas of the arts, especially painting, printmaking and film. Dupain was adamant that he “did not want to go back to the ‘cosmetic lie’ of fashion photography or advertising illustration” and studio fakery. Instead, he had embraced what he termed the “mechanistic” aspect of photography.

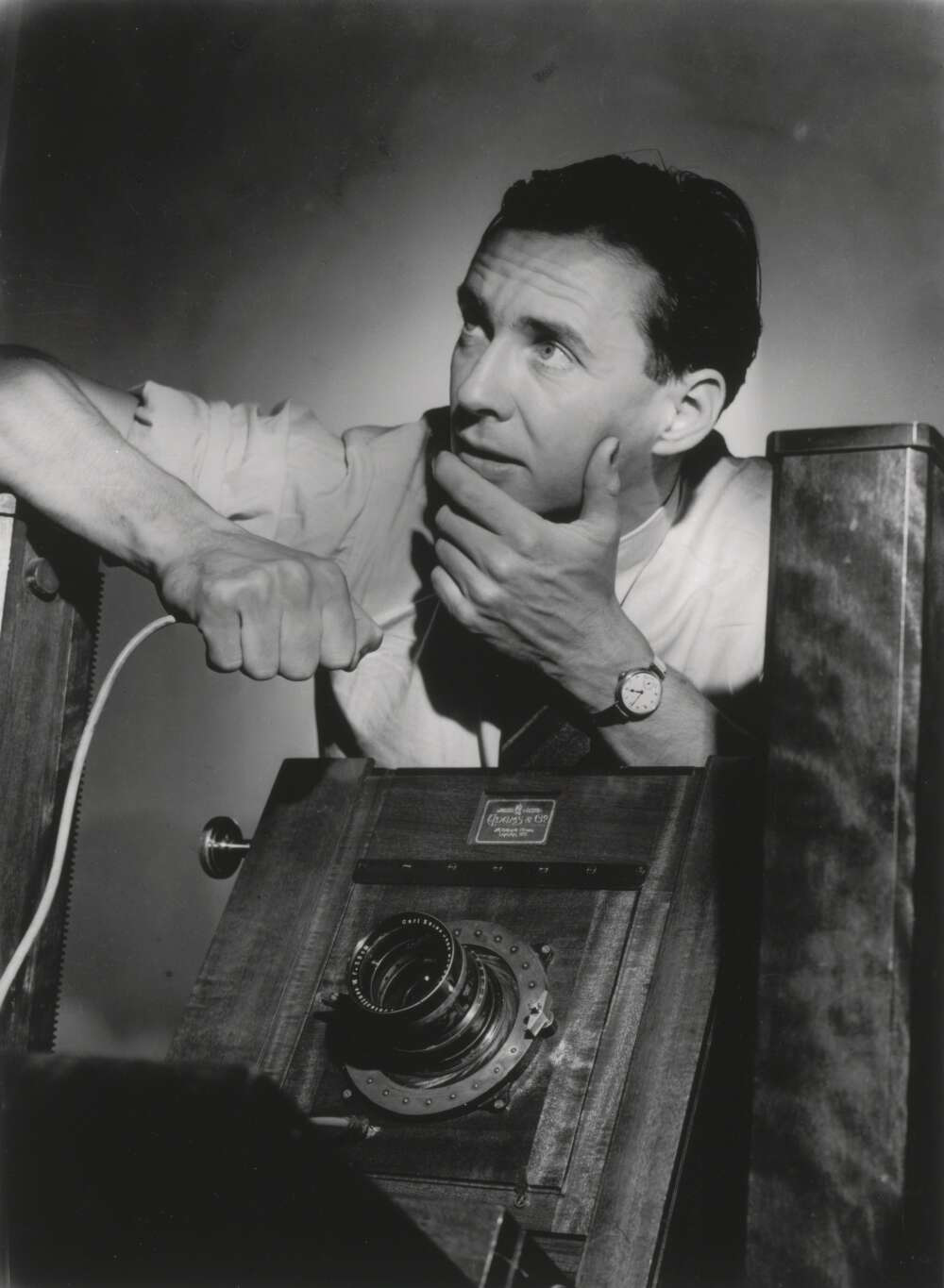

Before the flood: a Max Dupain self portrait from 1938. National Library of Australia

“Let it be automatic as much as possible,” he declared, “the human element being selection of viewpoint and moment of exposure, subsequent technicalities being performed skilfully and scientifically.” Although he did not state it publicly, his new stance meant repudiating the highly imaginative Man Ray and surrealist-inspired studio experimentation he had embarked on in the second half of the 1930s.

Equally importantly, Dupain revealed his conceptualisation of “a national photography [that] will contribute greatly to Australian culture.” He exhorted readers of Contemporary Photography to “let one see and photograph Australia’s way of life as it is, not as one would wish it to be. It is wasting the dynamic recording capacity of the camera to work otherwise.” The use of sunlight rather than artificial studio lighting was central to his vision.

He reiterated the commitment to realism in his aptly titled “Factual Photography,” the lead essay in the book Australian Photography 1947, also edited by Le Guay. Dupain’s essay roughed out a colourful history in which true photography had become lost “in the slimy depths of the half-arts for nearly a century” as artist photographers disastrously imitated the effects of other media. Only recently had hopeful signs started to emerge, eliciting some of his most impassioned and polemical writing.

The period of revolution is at hand and we are rediscovering the virtues of the old pioneers and applying them to our own ways of life. We have learned to respect the photograph for its own sake and to recognise its mechanical limitations. We wish to play no trick or indulge in fake or make-believe. We do not wish to be classified as “artists” or “pictorialists” but are bent on developing the aesthetic of the light picture with reference only to natural phenomena and not to the other graphic mediums.

Within this context he also sympathetically reviewed the photography of Douglas Glass for the magazine Art and Design 1, highlighting the intersection of their concerns: “It is the underlying truth about life that fascinates him [Glass], and his problem is to reveal this in pure photo-form.” Glass, who lived in England, had taken a lightning-fast trip across Australia, photographing people and places as he went. His subjects included what Dupain described as “aboriginals in their native state, the machine impinging on their domain,” which probably refers to Glass’s relatively positive representations of Aboriginal people for the time. (Now, such images are more likely to be understood as paternalistic, based on the assumption that Aboriginal culture in the 1940s was in a premodern state that was more desirable than the culture of a modern and decadent settler society.)

Glass’s photograph of an Aboriginal man posed in front of movie posters in Broome has the caption: “This shot shows the impact of imported rubbish on the natives. What a sordid lot the film stars look alongside the aboriginal.” The Aboriginal man depicted is in a semi-naked state, and is photographed in a heroic mode, from a low vantage point looking upwards and out of the frame.

Dupain was certainly not the only practitioner involved in rethinking the kind of personal or creative photography suitable for a postwar world. His former employee Geoffrey Powell also championed realism but from a politically explicit position that was informed by his Marxist and communist beliefs. In contrast to Dupain he saw himself as a social realist photographer rather than a documentary photographer, and argued that a politically and socially oriented approach was needed to help achieve productive change in society.

For the politicised Powell it was imperative that the conditions of the working class be documented by the best possible photographers in Australia — those willing to “pick up… [their] lenses and films for the more constructive purpose of helping mankind.” E.L. Cranstone was another committed documentarian whose social realist approach aligned with Powell’s.

A vastly different perspective was offered by the older Harold Cazneaux, who did not want to see contemporary photographers becoming “caught up in the new ‘speed up’ of life, with all the new cults and ideas, and the so-called modern art movement.” He hoped more enduring traditions would prevail and put his case in an essay, “Landscape Photography,” which followed Dupain’s “Factual Photography” in Australian Photography 1947.

“In our grand open spaces,” Cazneaux wrote reassuringly, “will still be found the beauty of sunshine and shadow, the waving grasses on the hillsides, the winding stream, the towering gum. Sincere art comes from heart and mind, and we will find such inspiration in the work of yesterday even if we are all involved in this super progress of so-called modern life and art.”

Dupain respected Cazneaux’s vision but did not share it. He wanted to look forwards, not backwards, and be a provocateur, not a mediator. But unlike Powell, Dupain did not have a direct or specific political agenda; he saw himself as a progressive photographer, not a political activist. In this capacity he was hugely disappointed that his provocations were ignored.

Regarding the lack of interest in his “Factual Photography,” he wrote: “Nobody wrote me threatening letters, nobody took me to task, nobody was emotionally stirred to even say one word against my stand. Negative response. Total negative. So you withdraw and consider. Stuff the lot says I. I will do what I have to do and keep on doing it until the very last.” He would, however, make a couple more public interventions. In 1950 he introduced a twist to his advocacy of realism and objectivity in another essay, arguing for “the emotional factor” in photography, which allowed for a psychological dimension.

While Cazneaux and Dupain thought differently about photography, their fondness for each other shines through their correspondence. Four of Cazneaux’s letters, written between April 1945 (when Dupain was in New Guinea) and November 1952, have survived. They are thoughtful and direct, with the older man affirming the younger’s abilities and prospects for a future that he knows he himself does not have.

In one (undated) letter Cazneaux marvels at Dupain’s success with miniature film: “Your eye sight must be jolly good and as you are a young man I suppose it is natural to work miniature film — I used this size 25 years ago & could not make a go of it — of course those days did not hold Superxx stuff & modern equipment.”

In his longest letter, written in February 1947, he recognises the shifts occurring in Dupain’s approach after the war. He hopes “things are working out for you in the way you would wish — I know that “the Studio” has left you cold & — it’s a great game this battling with Nature’s direct light — the possibilities are beyond our imagination.”21 And he is pleased that they have both been published in Le Guay’s Contemporary Photography magazine.

The letters are, however, suffused with poignancy. Cazneaux, whose health had begun to fail, asks for Dupain’s help in obtaining maps for a possible trip to Central Australia. He describes it as “an imaginative mind journey” for the present, but if his health improves he plans to set off for the Flinders Ranges and Alice Springs in the forthcoming winter months. “It may,” he acknowledges, “be too late for me but there’s no harm in thinking of it all the same.” The trip did not eventuate.

Touchingly, Cazneaux refers to discussions about photography both men hope will happen in the future. In a postscript to his 1945 letter, he assures Dupain, “Yes we will have that chat some day my lad,” deferring to a time when he will not be so busy and “free to look at pictures again.” Seven years later, the topic resurfaces, and Cazneaux generously responds to Dupain, saying: “Yes some day we could have a good chat over photography. I know we are together in the real spirit of the game despite differences in its practice — this is only natural.” Cazneaux died in 1953.

Once Dupain returned to his business in 1947 the immediate problem was to build up his clientele again and earn a satisfactory living. The environment was competitive, with Monte Luke, John Lee, Laurence Le Guay and Noel Rubie operating commercial studios specialising in portraiture, fashion and advertising illustration in Sydney. Russell Roberts was still Dupain’s most substantial rival.

The difficulties facing Dupain were highlighted by photographer David Moore, the son of architect John D. Moore, whom Dupain knew well. The twenty-year-old Moore approached Dupain asking to join his studio in 1947, motivated by his belief that Dupain was “producing the most interesting photography in the country.” Moore especially admired his documentary photographs of the city, and of people at work and leisure.

Much to Moore’s disappointment, Dupain was not able to take on additional staff, but he secured a job with Russell Roberts, working as assistant to photographer Margot Donald, whose creative talent he admired. Moore lost his job with Roberts in 1948 — due to the business’s financial difficulties, a number of staff were retrenched — and he approached Dupain once again. Only when Dupain’s sole assistant unexpectedly gave notice could Dupain offer him a role — photographing industrial subjects, architecture and products for advertisements.

Moore relished the three years he spent at the studio: “Working with Max released energy in me I didn’t know I possessed. The days were too short.” •

This is an extract from Max Dupain: A Portrait, published this month by HarperCollins. Special price $44.99 from Readings.