Speechless: A Year in My Father’s Business

By James Button | Melbourne University Publishing | $32.99

NOT long after his father died, the journalist James Button realised he had entered that part of life when the years behind you begin to number more than those ahead. As such realisations often do, it unsettled him. Some men buy a European car, others start looking up old girlfriends on Facebook. Button took a different, less trodden, path.

When a job offer appeared out of the blue, he left the world of journalism, where he had worked – and thrived – for over twenty years and joined the Australian Public Service as a speechwriter in the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. Button didn’t buy an Alfa Romeo; he went to work for Kevin Rudd.

He met briefly with the then prime minister, who asked a few questions and then declared in a kingly way, “I think I want to do this.” And before he knew it, Button had become Kevin Rudd’s PECA: principal editor and communications adviser.

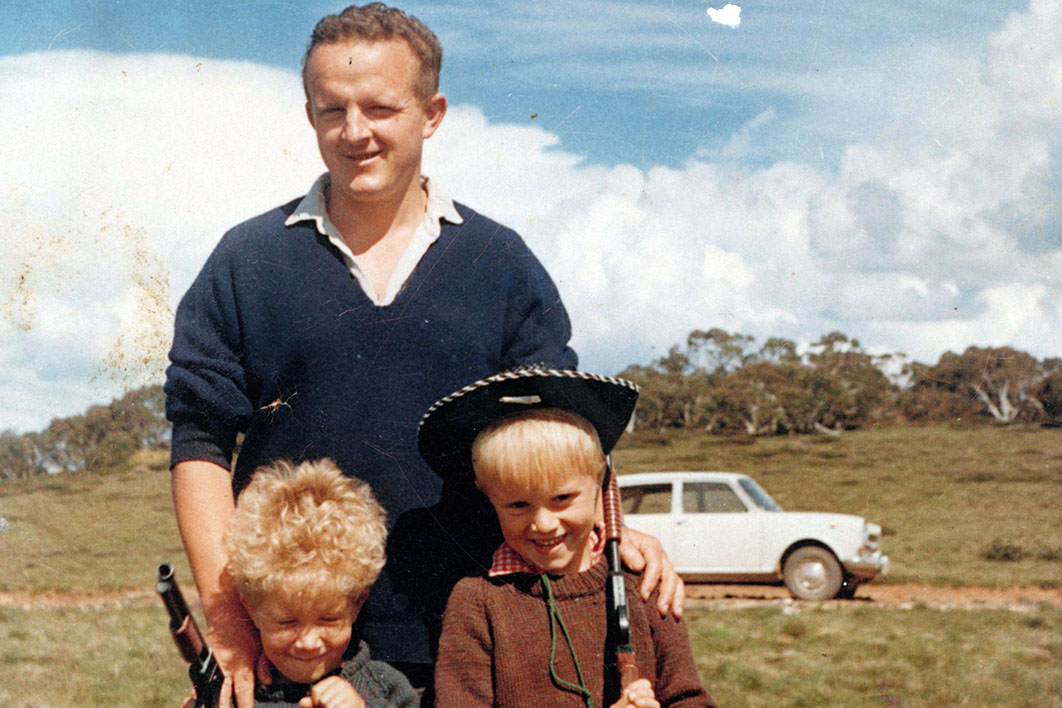

To understand why he took this course, it helps to know that James Button’s father was the respected Labor stalwart, John Button. Except for the traditional flirtation with politics as an undergraduate, Button junior was a lifelong observer of the great game – albeit with a ringside seat. But when his father died, Button began to question his own priorities. Hadn’t his father done more for Australia by wading through the quotidian drudgery of parliamentary politics than he had ever achieved in the media?

As a boy Button had watched as his dad went off to the national capital every week, and now he was making the same lonely journey in order to experience that world for himself. Unlike his father, Button hadn’t got into caucus or cabinet, but his position was close to the centre of things in the machinery of state. And Button was more than happy to do his bit by labouring away in a word factory dedicated to producing prime ministerial speeches.

After an initial burst of “face time” – a couple of extended meetings – Button rarely saw the PM again, and though he seems to have been eager and hard-working very little of what he wrote was ever used. In spite of his hopes, Button never got the chance to find where that island of a man, Kevin Rudd, resides on the map.

Later, he found out later that took an instant dislike to one of his early drafts, chucked a wobbly, and that was pretty much it. The former PM might be a peripheral character in Button’s book, but the portrait he paints of him is the latest in an increasingly large tally that exposes Rudd as a micromanaging control freak with a volcanic temper.

Though obviously frustrated by his non-relationship with Rudd, Button came to appreciate his fellow public servants. He discovered a bureaucracy where smart people work hard and try their best. It’s a very rare book on Australian politics that makes life in the public service sound vital and interesting, but Button’s does. Working in the Strategy and Delivery Division of PM&C he met men and woman who knew things and wanted to use their knowledge to make a difference – ideas people who sought out problems to solve and tried to explain their solutions in a clear, accessible way. He clearly admired them and enjoyed working with them.

So it’s strange and a little unfair that Button’s book has been attacked, most notably by Ian Watt, the head of PM&C, for its “corrosive” disclosure of the author’s conversations with Kevin Rudd. According to its critics, the book flouts the public service’s rules of confidentiality. Maybe Button’s book does go against the traditions of the bureaucracy, but at the same time it doesn’t reveal anything that needs to be kept secret and its overall portrayal of the public service is highly positive. In fact, it’s the type of book that might even encourage bright, idealistic Australians to join the public service.

Early on during his Canberra sojourn a senior official described Button as the department’s snow leopard – “a rare and beautiful creature… always at risk of extinction.” And so it proved. Button lasted just over a year and then returned to his family in Melbourne and started work on his book.

THOUGH he fought the good fight against the use of jargon in the public service, Button did grow to appreciate some of the bureaucracy’s vernacular. He liked, for example, the phrase “program confetti,” which describes what occurs “when government tries to solve a big problem with a rush of small programs.” He also liked the term “granular,” which refers to the very detailed analysis of a problem.

In this sense, Button’s writing can be pleasingly granular. He’s very good – as you would expect – on journalists and what makes them tick, and he soaked up a lot of telling detail during his short time in Canberra, but he is especially good at describing the texture of political life. “I’m not one of those Australians,” Button writes, “who say, ‘They’re all a bunch of bastards.’ I have an instinctive sympathy for politicians.”

After all, he’s seen the political life from the inside. “Politics was the phone ringing at all hours, the barbeques in our backyard, the men with briefcases slipping in and out of our house on secret party business, the air in my father’s house dense with the smoke of his Peter Stuyvesants.”

And, of course, politics was the engine of his father’s life; it was the family business. By all accounts John Button was an immensely gifted and complex man: he was a quick-witted absurdist; a disarmingly honest pragmatist; a one-eyed Geelong supporter; a lover of books and women; but above all a committed Labor man who never renounced the faith.

Button is both inspired and a little awestruck by his father’s capacity for political commitment, particularly because he understands intimately the costs it could bring with it.

In 1982 something happened in the Button family that threw all their lives into despair and disarray. The family’s middle child, a troubled boy named David, died of a heroin overdose at the age of nineteen. As Button describes it, “Beneath our family the ground opened, then it closed again.” His father – soon to be a key minister in the Labor government he’d toiled so hard to achieve – coped through working, but his grief never left him. And how could it? A couple of times a year he’d drink too much and break down. Tellingly, Labor’s election victories would sometimes bring it on. The thing he had sacrificed so much of his family life to achieve had come about, but Dave was not there to see it.

The man who had so loved the political life came to regret living it. He once told an interviewer, “You know, I sometimes think… I’m conceited enough to think, I suppose, that it may not have happened if I’d been home.”

JOHN Button’s funeral was a Labor funeral. Paul Keating spoke. John Cain spoke. Even Bill Hayden spoke. The former Labor Party leader recalled that bitter day in 1983 when Button told him he had to step aside for Labor’s messiah-in-waiting, Bob Hawke. The episode had ended their friendship but in later life the two were reconciled. And Hayden could now accept that Button had delivered the blow that killed his leadership with honesty, courage and grace.

“They were old men singing their ballads”, writes James Button, “telling of the years camped on the plains before they finally took Troy.” Afterwards, ever the tribal chieftain, Keating said of the service, “No one puts on a show like the Labor Party. The other lot could never have done this.”

Button also spoke. He spoke less of the Labor saint and more of the man. He ended his eulogy with a story of his father standing at his front gate watching protectively as his remaining sons, James and Nick, disappeared into the Melbourne gloom one evening after a day at the footy. “We shook hands and half hugged, in our awkward, warm way. Nick and I walked down the street. I looked back and he was standing there smiling… I looked back again and he was still standing there, looking after us.”

It was only weeks later that Button realised he had delivered the eulogy without mentioning his brother, Dave, and then, too late, he remembered the real point of the story. “As we walked away from him down the street I had said to Nick, ‘Poor Dad, his life is hard.’ He understood. It was just four years since David had died.”

Button’s book is about many things: it’s about political commitment, where it comes from and what sustains it; it’s about the thrills and failings of journalism and the power of language; it’s about loyalty and family and regret. In other words: it’s an essay – a beautifully written, personal essay; by turns tender and wise and, when necessary, brutally honest. But above all else, it’s an offering of love to a father and a brother. •