Not everything about Facebook or its pervasive rise is unique to the twenty-first century. More than a decade before Alan Turing’s influential 1936 paper setting out the blueprint for the modern computer, the first “facebooks” appeared. They were created by students not at Harvard but at elite French universities and, like their present-day counterpart, they were the product of the irresistible rise of another technology: photography.

The story can be sifted from massive collections of secret files on individuals held by the French National Archives. Earlier this year a thought-provoking exhibition at the archive, Fichés?, made use of the sensitive material to trace how attempts to identify individuals evolved with technology. It asked the simple question: how did the photographic portrait come to be the most ubiquitous key to personal identity?

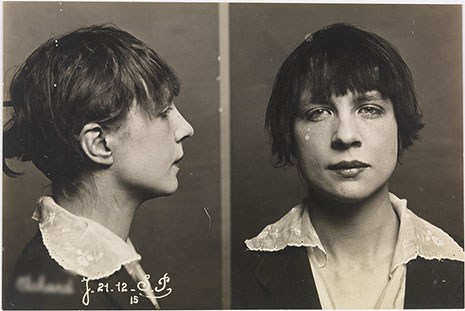

The earliest photographs date back to the 1820s. As techniques were refined, the potential to produce exact reproductions of the visual world piqued the interest of more than just a handful of artists. By the middle of the nineteenth century the Parisian police force had seen their potential, and began to use photographic portraits to register criminals. Physiognomy – a technique based on the belief that a person’s character was reflected in their appearance, and particularly their face – was still influential. One police officer, Alphonse Bertillon, developed an elaborate anthropometric system so that photographic portraits assembled by the force could be standardised.

It was the repression of the Paris Commune in 1871 that gave impetus to the rise of the mug shot. Police sent photographers into the prisons to photograph those arrested, and then they composed the first criminal record cards to include a photographic portrait. At about the same time, improvements in technology made it possible for police agents to take their own shots. A single bureau was established to oversee a central “database” of record cards. Photos of wanted criminals were distributed in a bulletin and also published in the press.

By the end of the Great War it had become commonplace for French people to have their photograph taken for administrative purposes. The portraits were required for a whole range of new identity documents. Entitlement cards for war veterans and driver licences were introduced at this time, as were identity cards for foreigners on French soil. (Passports as we know them did not yet exist.) Before long people attached photographs to the most innocuous official documents.

It was at this point that the first “facebooks” appeared. Students at elite French universities produced yearbooks made up of a photo of each member. The practice soon spread to government departments and large companies as those students stepped into influential positions. Some eighty years later Facebook initially followed a similar trajectory. After a successful launch in Harvard, it was introduced first into other Ivy League universities and then into major corporations before being made available to the general public.

The exhibition also examined a darker side of the growing use of photographic portraits. Archival records show that when French police began to build collections of individual record cards, not all parts of the population were catalogued with the same fervour. Roma and other nomadic peoples served as “models” for what was ostensibly the refinement of the anthropometric standards developed by Bertillon.

As state-sanctioned racism built to the crescendo of the second world war, the photograph became a tool of control and repression. In 1935 the French government set up a sophisticated central record agency to “administer” the increasing number of refugees fleeing Nazi Germany. The first French national identity cards were issued by the Vichy regime in 1940, and they included racial descriptions as well as information, where relevant, on how and when the bearer had attained French citizenship. The cards facilitated the work of the Nazis.

The worst abuses of the Vichy regime seem an age away, but vestiges of that early craze for attaching photographic portraits to anything and everything remain. In France it is still common for job applicants to send off their curriculum vitae with a photo attached. Despite claims that the practice has made it possible for employers to discriminate, subconsciously or not, against candidates of foreign and particularly Arabic appearance, most French people continue to put a face to their name. Those who choose not to run the risk of a potential employer suspecting that they have something to hide.

It takes an exhibition like this to remind us that the photograph played a role in building professional and social “networks” well before the word was applied to groups of people, let alone a group of computers. And in a world where photo ID has become so common, it is worth reflecting on the remarkable fact that only a century ago many people considered having their photo taken to be an invasive and even dehumanising experience. The expression “to shoot a photo” dates back to the nineteenth century. Were those people right to be concerned, given what we now know about the eerie negatives of the pre-digital age photograph?

Because French archival law protects documents relating to individuals for fifty years, the exhibition could not make use of any records from the 1960s onwards. But the truncation of the story only makes the contrast with the present-day abundance of photographs all the more stark. On sites like Facebook, portraits – when people choose to post one at all – are just a pixel in a kaleidoscopic representation of life. It would seem that we are in the process of polishing a new facet in the history of visual identity. •