In the years leading up to the first world war the Colorado coalfields were a little patch of feudalism in the middle of modern-day America.

Coalminers lived as vassals, housed in company towns, patrolled by company guards. They couldn’t leave the area without permission, and strangers couldn’t enter. They were paid by the ton for the coal they extracted, but no one was paid to make their workplace safe; this maintenance labour was derisively known to management as “dead work.” The mine owners habitually rigged the coal scales to favour their side of the ledger. All of this was illegal under Colorado law, but the state government turned a blind eye.

Violence was commonly used against the miners and their families; many were beaten by thugs working for the notorious Baldwin–Felts Detective Agency. In one famous case, a National Guard commander ordered a cavalry charge — sabres drawn — against a crowd of protesting miners’ wives because the women had dared to laugh when he fell off his horse.

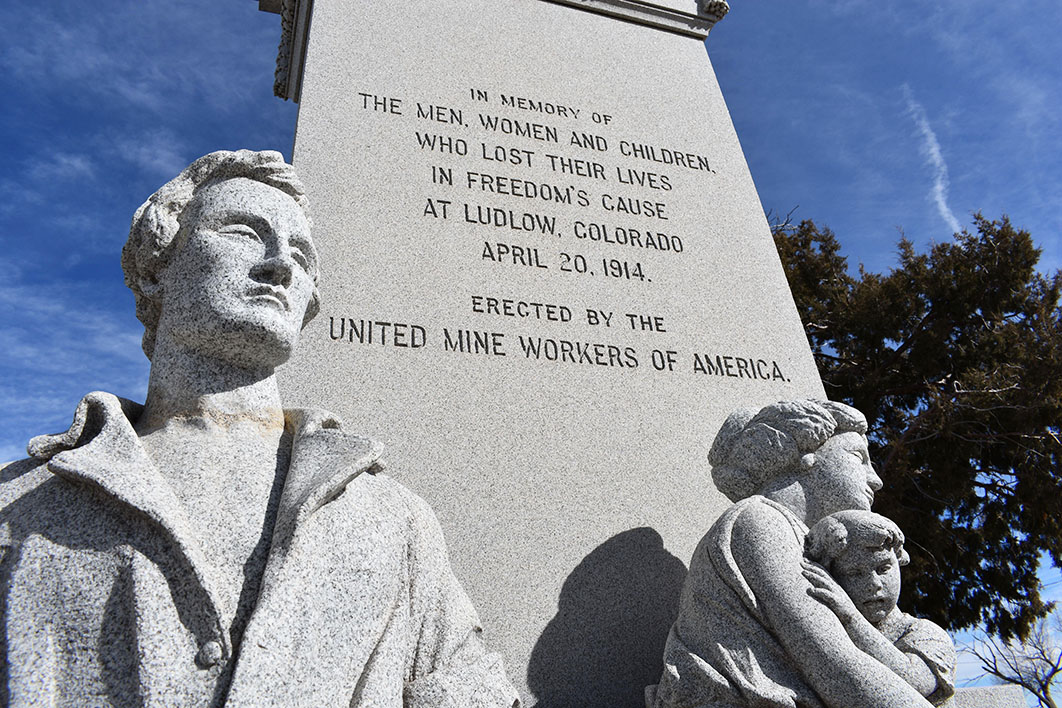

When the United Mine Workers of America organised a strike for better pay and conditions at a mine owned by the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, trouble soon came over the horizon. Twelve hundred miners and their families were evicted from the company town and moved to a makeshift union camp known as White City, where they lived in tents. Their new home was next to a railway depot called Ludlow.

On 20 April 1914, shooting broke out between the striking miners and the company militias. Three strike leaders were captured and shot dead. Seventeen women and children, including three infants, were killed when the militias set fire to the camp. For the next week, a civil war of violent skirmishes led to dozens more deaths on both sides. Peace was only restored when president Woodrow Wilson sent in the US army.

The man held most responsible for the disaster was John D. Rockefeller Jr, heir to the Standard Oil fortune, who part-owned the mine. The Ludlow Massacre is credited with cementing Rockefeller’s commitment to philanthropy, some say as an act of atonement. Until his death in 1960 he funded many and various good works. In 1922, for example, he financed the study of industrial relations in the economics department at Princeton University.

It’s a long way from Ludlow in 1914 to Princeton University’s Firestone Library in the 1980s. This is where the economists David Card and Alan Krueger first met and began to collaborate on labour economics, courtesy of Rockefeller’s original donation.

In 1994 the pair published a paper examining the widely held economic orthodoxy that an increase to the minimum wage led inevitably to higher unemployment. This was always a popular theory in business circles, probably because it accorded so neatly with the prejudices and interests of business owners. I’m sure it looked like common sense to J. D. Rockefeller Jnr. But it had never been studied in the wild.

In their paper, Card and Krueger pioneered the use of “natural experiments” to interrogate economic assumptions. New Jersey had raised its minimum wage in April 1992, but its next-door neighbour, Pennsylvania, hadn’t. This gave them a perfect opportunity to study and compare the real-world effects of giving the lowest-paid workers a little bit more. To do this they surveyed over 400 fast-food restaurants in both states.

And what did they find? They found that the restaurants in New Jersey, contrary to conventional wisdom, had taken on more workers. An economic shibboleth was toppled.

It turns out that lifting the minimum wage improves labour force participation among society’s poorest workers and increases their productivity as well. Business owners benefit from lower staff turnover and reduced training costs. The economy more broadly also benefits — from increased consumer demand — courtesy of having more workers, with more money, spending more.

Over the past twenty-five years Card and Krueger’s work has supplied the intellectual firepower for minimum wage campaigns across the United States and around the globe. In 2015, for example, Germany introduced a minimum hourly wage set at a uniform national level. Business — and some sections of the German media — warned of job losses in the hundreds of thousands. But a new study of the German experience has found that “the minimum wage significantly increased the wages of low-wage workers without lowering their employment prospects.” Rack up another win for Card and Krueger.

And then just a week ago came the ultimate accolade. Card was awarded the Nobel Prize for his work on the minimum wage. But not Krueger. Tragically, he died by his own hand in 2019 at just fifty-eight, and unfortunately a Nobel is never awarded posthumously. As Card told the New Republic, “He probably would have enjoyed getting the Nobel Prize more than me.”

It was once the orthodoxy to treat workers like serfs, despite the terrible costs — to individual lives, to society and to economic performance. And even now, despite the work of Card and Krueger, some people still believe it’s a good idea to pay as little as possible to low paid employees and tell them it’s for their own good. Perhaps this year’s Nobel Prize will finally lay that fallacy to rest. •