One of the striking things about reading a selection of the torrent of books produced in recent years about US–China relations, written by experts either in America or in the People’s Republic, is the claustrophobic tone they share. This is not to denigrate their quality as academic or specialist literature. Even books like David Lampton’s Following the Leader: Ruling China, from Deng Xiaoping to Xi Jinping (2014) or David Shambaugh’s China Goes Global: The Partial Superpower (2013), which are ostensibly about solely Chinese issues, have a strong US-centric flavour, however powerful the insights and arguments they contain. Hovering over these and many other American and Chinese works is a sense that both countries are fiercely jealous of their relationship with each other, and don’t take it too well when anyone else butts in.

This is understandable. These are the world’s two major economies, and on most indicators, at least of hard power, they rank number one and two. India, Brazil and Russia are not in the same league, no matter what their developmental aspirations. The only other contender, the European Union, is somewhat stymied by not being a nation-state at all. In this context, it is natural enough that the two big powers are talking to, working with and observing each other so intensely.

But there are times when the US–China “dialogue” might be improved with some outside ballast. In an essay by Bates Gill and Andrew Small in a recent book about EU–China relations, China and the EU in Context: Insights for Business and Investors, this question of potential trilateralism got some attention. Together, the European Union, China and the United States constitute over half of global GDP. They have dense and diverse links with each other. On many geopolitical issues, whether it’s combating climate change or dealing with the global financial infrastructure, they have plenty of common ground. Despite this, formally at least, they almost never sit down solely as a group of three, at least at government level. No one has been talking about a G3, and there is little likelihood that such a grouping is going to exist any time soon.

The simple fact is that the European Union is not regarded as having the foreign policy autonomy that would be necessary for such a forum to work. Its big chance came in the early 2000s when there was the slight possibility it would defy the United States and lift the largely symbolic arms embargo imposed on China after the unrest of 1989. But a few phone calls from Washington to European capitals meant that never happened. The European Union rapidly disappeared back into the American stable, and there it has remained.

A country like Australia can show, though, that the creaking joints of this US–China adult dialogue, where other partners are granted a few seconds every so often and then told to wait outside while decisions are being made, might be getting closer to breaking point. Like many other countries, Australia is increasingly dependent on good links with Beijing for its economic welfare. So far, the policy-making elite in Canberra has handled this using a framework in which there is a clear dichotomy between security and economy, which means Australia can plant its allegiances, without incoherence, in two different places depending on which sphere of policy it is talking about. But in the real world, everyone knows that this neat division is fallacious. Strong economy equals strong security. And more and more of Australia’s money comes from its northern regional neighbour, not its longer-term Pacific-facing pal.

One strategic opportunity that exists now is coming from the Chinese side. Ironically, it is they, rather than the jealous United States, who seem to want to grant a little more space for others at the adult table. They may be doing it as leverage on Washington in specific areas, but if it offers chances for countries like Australia to develop a more diversified, nuanced foreign policy stance, then any pragmatic actor would want to take the opportunity.

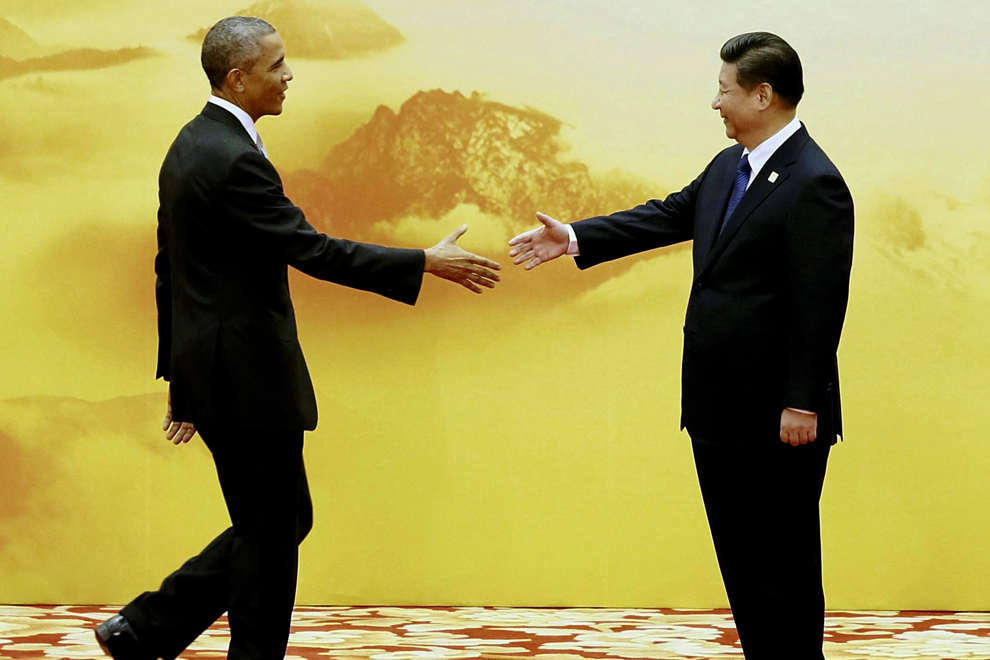

There are other options too. The United States often sounds like it knows everything, knows what to do about everything and knows when to do things, and anyone who has sat among US policy-makers discussing China knows it can be an intimidating experience. The US–China climate change accord signed last November by Obama and Xi was an impressive example. But underlying the bravado there is more circumspection. The literature about China from the United States is often polarised, revealing a lack of intellectual consensus about the sort of opportunity or threat China offers and what, in the medium to long term, Washington might be able to do about it.

Contributing ideas to this debate is important. In that realm, luckily, there are no doormen guarding access to privileged meetings and summits that only the United States and China can attend. Ideas can seep through, and have surprisingly dramatic impact. An Australian academic like Hugh White, writing about how China might be testing and rethinking its regional role, is a good example here, offering the sort of thinking that is rare in the great industry of academia and think tanks in the United States.

No one could deny that the United States and China have the greatest influence over global issues at the moment. But the tight way in which they embrace each other and often exclude others from their formal dialogues needs gentle challenging. The danger at the moment is that they may have become married to a paradigm within which they only see what matters to each other, and have forgotten the world outside. If they stepped out of this tight context, they might well be able to see things in a fresh way, and find some new solutions. •