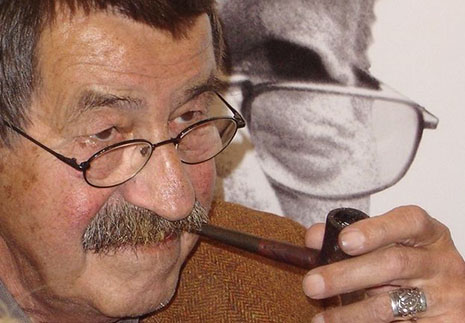

GÜNTER Grass has done it again: he’s put himself on the front page and at the head of the evening news bulletin by styling himself as the lone voice defending the truth and speaking out against an injustice.

On 4 April, Germany’s Süddeutsche Zeitung, Italy’s La Repubblica and Spain’s El País published a poem in which Grass articulated his concerns about Israel’s arsenal of atomic weapons and criticised Germany for selling it a submarine capable of firing missiles armed with nuclear warheads. For more than a week, the poem, or rather the outrage it triggered, dominated the German print and electronic media. Never before in the history of the Federal Republic had a work of poetry caused such a storm.

Most of the response in editorials and from politicians, fellow writers and other public intellectuals was damning. Outside Germany, the reaction was overwhelmingly unfavourable, ranging from irritation to outrage. The Israeli government went so far as to blacklist Grass and ban him from entering the country. Only the government in Tehran, predictably enough, was delighted by his intervention: “I read your literary work of human and historical responsibility,” deputy culture minister Javad Shamaqdari was quoted as telling Grass in a letter, “and it warns beautifully.”

Ordinary mortals who want to voice their concern, indignation or outrage resort to writing to the letters pages of their local paper or to calling talkback radio. They might share their views on blogs, via Twitter or on Facebook. Those more confident of their standing might issue a press release. The eighty-four-year-old author of The Tin Drum and other highly regarded novels, winner of the 1999 Nobel Prize for Literature, poet, sculptor and graphic artist, a man often portrayed as “the conscience of the German nation” – who is also (and this is important for understanding the response to his words) a former member of the Waffen-SS – penned his thoughts in the form of a prose poem, “Was gesagt werden muss” (“What Must Be Said”) . He would have known that whatever German broadsheet he approached, the poem was going to be printed in full, appear on the front page, and capture Germany’s full attention.

While the text’s content has been controversial, there has been no dispute over its merits as a poem. “A literary mortal sin,” prominent songwriter Wolf Biermann found. A professor of aesthetics, Bazon Brock, believed Grass’s scribbles gave poetry a bad name. Fellow Nobel laureate Herta Müller called Grass a megalomaniac for sending his text to three newspapers in different countries, and said it contained “not a single literary sentence”. Wordy, clumsy and overly didactic, “What Must Be Said” would have to rate among the worst of Grass’s poems. Reminiscent of the didactic poetry of Bertolt Brecht, but without the latter’s rhythm and economy, it is little more than an unedited stream of consciousness. Obviously the editors of the Süddeutsche Zeitung, a highly regarded liberal broadsheet published in Munich that has one of Germany’s best arts sections, hadn’t made the decision to publish on the basis of its merits as a work of art.

In the poem, Grass takes issue with the delivery of a German-built submarine to Israel. He objects to the arms deal because the submarine is capable of carrying nuclear missiles which could be used to attack Iran and “wipe out the Iranian people.” He criticises what he regards as the West’s hypocrisy: insisting that Iran not be allowed to develop nuclear weapons, while condoning Israel’s nuclear capability, which, Grass claims, “jeopardises an already precarious global peace.”

Grass devotes much of the poem to pondering his failure to speak out earlier. He says that a German who criticises Israel is likely to be punished, not least by being labelled an anti-Semite. But, in what reads like an act of heroism, he has decided to “break his silence” because the matter is urgent and because “we, who as Germans are already sufficiently encumbered, / could become accessories to a crime / that is predictable, which means that our complicity / could not be erased / by any of the usual excuses.”

Grass has been taken to task, rightly, on several accounts. He misrepresents the situation in the Middle East. The Israeli government has indeed considered a pre-emptive strike against Iran to foil that country’s nuclear program. These plans have been hotly debated in Israel itself, and have engendered critical responses from Israel’s allies. “What must be said,” the Israeli historian and journalist Tom Segev noted in Tel Aviv’s liberal Haaretz newspaper, “did not have to be said because it has already been said by many others, in Israel as well.” Such a strike would almost certainly target Iran’s nuclear facilities rather than its people. And the rationale for an Israeli attack would be the declared intention of the Iranian leadership to wipe out the people of Israel – something Iran could conceivably do quite easily once it has built an atomic bomb.

Grass also suggests that it is impossible to criticise Israel in Germany. If by “Israel” he means the Israeli government, then such a claim is patently wrong. German politicians and intellectuals have long criticised Israel for its policies in the Occupied Territories, in particular. In February last year, Angela Merkel called Israel’s prime minister Netanyahu to remonstrate with him on account of Israel’s dilatory approach in its negotiations with the Palestinians. In December, Germany, together with three other members of the UN Security Council – Portugal, France and Britain – condemned Israel’s settlement policy. After a visit to Hebron only last month, the leader of the Social Democrats, Sigmar Gabriel, opined on Facebook: “This is an apartheid regime which cannot be justified by any means.” Gabriel was roundly criticised for this comparison and eventually apologised, but his comment nevertheless is evidence that Grass’s insinuation of a taboo against such criticism was not justified. Incidentally, Gabriel has been one of only a handful of prominent German politicians who has stood by Grass in the current controversy.

GABRIEL’s intervention may have been prompted by loyalty as much as by sympathy for the sentiments expressed in the poem. Grass has long been associated with the moderate left and has often campaigned for the Social Democrats. As a prominent public intellectual of the left, he is intensely disliked by many on the right. The poem presented his political opponents with a golden opportunity to remind the public of Grass’s achilles heel.

In 2006, Grass published his memoirs, Beim Häuten der Zwiebel (published in English as Peeling the Onion). A few weeks before the book’s eagerly awaited release, he gave an interview in which he revealed that he had been a member of the Waffen-SS, the elite military units that were formally the armed wing of the Nazi Party and which existed alongside the regular army. While the Waffen-SS was not in charge of concentration camps, some of its units were responsible for war crimes; after the war, the SS as a whole was declared a criminal organisation.

The interview may well have been designed to raise the public’s anticipation ahead of the memoir’s publication. But it set off a discussion about Grass’s war record which also ensured that the 479-page memoir is known mainly for an episode that Grass explores in a little more than a page.

The mere fact that he had been a member of the Waffen-SS should have mattered little. He was born in 1927, and drafted for the Waffen-SS as a seventeen-year-old. He did not join the Waffen-SS as a volunteer (although he had volunteered to join the regular army as a fifteen-year-old). He was not involved in any war crimes.

In Peeling the Onion, he doesn’t try to reinvent himself as a seventeen-year-old anti-fascist: “There is nothing carved into the onion skin that can be read as a sign of shock, let alone horror… I did not find the double rune on the uniform collar repellent.” Nor is he professing innocence: “Even if I could not be accused of active complicity, there remains to this day a residue that is all too commonly called joint responsibility. I will have to live with it for the rest of my life.” When he was taken prisoner by the Allies, Grass didn’t hide the fact that he belonged to a Waffen-SS unit.

The reason that the revelation in 2006 caused a sensation was because it came so late. For sixty years, he had chosen not to own up to the fact that he had once belonged to an organisation that was instrumental in the Holocaust.

Mathias Döpfner, chairman of the board of the Springer Corporation, the publisher of the tabloid Bild and one of Grass’s perennial targets, would have taken pleasure in denouncing Grass in an opinion piece titled “The Onion’s Brown Core,” which appeared in Bild the day after the publication of the poem. His opening sentence identifies why he (and many others on the political right) dislike Grass so strongly: “Günter Grass likes nothing more than to remonstrate with the Germans and appeal to their conscience.” Döpfner draws a connection between Grass’s self-confessed silence before the publication of the poem, and the silence that preceded Peeling the Onion: “‘But why did I remain silent thus far?’, Grass writes. One is inclined to ask in return: Why did he remain silent for sixty years about his membership of the Waffen-SS?… ‘Peeling the onion’… Grass has now arrived at its very centre. And the onion’s core is brown and stinks.”

The claim that Grass forfeited the right to speak out because he was coy about his Waffen-SS membership may be a vengeful ploy by those who have long borne the brunt of Grass’s moral indignation, and a cheap attempt to match the poet’s self-righteousness. But Döpfner and others have also accused Grass of being a Nazi and anti-Semite, suggesting that the seventeen-year-old and the eighty-four-year-old shared a hatred of Jews and a fondness for Nazi ideology. Their argument is anything but subtle: whoever criticises Israel by failing to distinguish between the Iranian aggressor and the Israeli victim is guilty of anti-Semitism.

Yet the suggestion that Grass’s poem reeks of anti-Semitism shouldn’t be dismissed lightly. The poem is remarkable not so much because of its ludicrous claims about supposed Israeli designs to annihilate the Iranian people, but because of its insinuation that a taboo prevents Germans from speaking out against Israel and that anybody violating that taboo would be accused of anti-Semitism. Such an argument is reminiscent of the claim that there is a taboo preventing, say, non-Aboriginal Australians from criticising Indigenous people, or Americans of European descent from criticising African or Native or Asian Americans, and that any violation of such a taboo triggers accusations of racism. It resembles the tactic of the racists who introduce an odious statement with the preamble, “political correctness prevents me from saying this,” and then go on to say exactly what they think. A variant of the “but one of my best friends is Aboriginal/ African American/ …” line also appears in “What Must Be Said”: Grass refers to Israel also as “a country I am and always want to be close to.”

While Grass is no anti-Semite, his poem gestures towards the vocabulary and the mindset with which he grew up. Nazi ideologues successfully conjured a Jewish conspiracy that thwarted legitimate German ambitions and could therefore be held responsible for German ressentiments. Grass does not blame Jews or Israel for feeling resentful – but there is no doubt that his views about the legacy of the Nazi past, both Germany’s and his own, are tainted by resentment. He resents the fact that he has to live with “it” – be it guilt, responsibility or shame – “for the rest of [his] life.” In the poem, he is concerned about potential German complicity in an Israeli pre-emptive strike because the burden Germans have to carry is already heavy enough. Raphael Gross, director of the Leo Baeck Institute in London and of the Jewish Museum in Frankfurt, has rightly pointed out it is so difficult to overcome National Socialism precisely because of the failure to recognise the longevity of Nazi mentalities and morals.

Günter Grass is one of the greats of postwar German literature (although, in my view, he does not come close to being the greatest). His reputation as a writer shouldn’t be mixed up with his standing as a public intellectual. In his latter capacity, he did play an important role on many occasions, not least because he could be counted on as somebody who wouldn’t shy away from speaking out in the face of a seemingly overwhelming consensus. Thus he criticised the rushed process of reunification, and he resigned as a member of the Social Democrats when his party agreed to the so-called asylum compromise of 1992, which led to a change of the German constitution’s guarantee of a right of asylum. In both those cases, it was courageous of him to take a stand.

But when it comes to his own past, he has been a troubled soul. And since he has long been convinced that his views deserve a broad audience, the readers of his books and the public at large have been privy to his inner conflicts. Much of his writing, while purporting to be about Germany (or, in the case of “What Must Be Said,” about Israel), is in the last instance about his own demons. It is telling that his controversial poem begins with the words, “Warum schweige ich,” “Why do I remain silent,” and thus with the writer’s “I” (rather than with Israel, which is mentioned only twenty-eight lines later).

The publication of “What Must Be Said” was not the first time that Grass got into trouble in Israel. Only six months ago, in an interview with Tom Segev, Grass opined that “the madness and the crime were not expressed only in the Holocaust and did not stop at the end of the war. Of eight million German soldiers who were captured by the Russians, perhaps two million survived and all the rest were liquidated.” The use of the verb “liquidate” and the (incorrect) reference to six million dead German POWs could be read as saying that there was a German equivalent to the Holocaust and that Germans were as much victims as Jews. At the time, Segev himself excused Grass, saying that the figure of six million German victims came up “in the heat of the moment.” That was a kind interpretation, but perhaps one with more than just a grain of truth to it.

In the poem, Grass refers to Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad as a Maulheld, a loudmouth. It is one of Grass’s mistakes in the poem not to take seriously the man who wants to wipe Israel and its people off the map. If there is a Maulheld in this story, it is Grass himself. He has the tendency to pontificate at the top of his voice, to speak before he thinks, and to exaggerate first and qualify later.

NOTWITHSTANDING his prominence, Grass’s recent intervention, much of it politically silly and artistically of little merit, should not have preoccupied the German opinion pages for many days. Neither should it have prompted Israel’s government to declare him a persona non grata (which then prompted Grass to liken Israel’s interior minister to Erich Mielke, the East German minister responsible for the Stasi, who once banned him from visiting the German Democratic Republic). It is unfortunate, too, that the controversy failed to raise a few issues that are probably worth more consideration than the Nobel laureate’s ill-chosen words.

First, Grass actually made a suggestion in his poem that is worth further discussion: namely that an agency ought to have the right to inspect Israel’s nuclear facilities. In an ideal world, that agency would also have unfettered access rights in all countries, including the United States and Russia.

Second, the spectre of anti-Semitism, raised by Grass himself, deserves closer attention. What is the relationship between anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism, particularly in Germany? And what is the link between anti-Semitism and the rabid pro-Zionism that has long been advocated by the Springer Corporation via Bild?

Third, the controversy over “What Must Be Said” has been remarkable more because of the response to the poem than because of the poem itself. What moved so many of Germany’s public intellectuals to rush into print or onto television shows to distance themselves from Grass? What does it mean when fellow writer Rolf Hochhuth told Grass in an open letter, “I am ashamed as a German of your preposterous silliness”? Did he seriously believe his reputation would be tarnished by Grass’s intervention?

German newspaper editors and talkshow hosts seem to have concluded that this particular debate is over. All those who conceive of themselves as opinion-makers have said their piece. If it was a contest then Grass’s critics seem to have won it convincingly. Besides, Grass himself retired hurt; he fell silent because he was admitted to a Hamburg hospital on 16 April, apparently with heart problems. But a survey of opinion pages and of Germany’s famed Feuilleton, the culture sections of the print media, provides a skewed picture. Grass has had his backers. During the last TV debate about the poem, on 15 April, the studio audience applauded those who defended Grass (and criticised Israel) rather than Grass’s critics. The German blogosphere, the comments sections of news media websites, the letters pages and numerous non-representative opinion polls suggest that a majority of Germans sympathise with Grass’s views.

Some of Grass’s critics, such as the historian Daniel Jonah Goldhagen or Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung editor-in-chief Martin Vogler, noted that his views resemble so-called Stammtischparolen, opinions uninhibited by political correctness and informed by prejudice and jingoism. Little attention has been paid to the fact that the Stammtisch, the proverbial regulars’ table in the pub, came out in support of Grass, and that its views appear to be at least as much informed by a deep-seated resentment as Grass’s. Grass himself, by the way, has been surprisingly unconcerned about the applause he has been receiving from unreconstructed anti-Semites, and about the legitimacy he has bestowed on certain Stammtischparolen.

Perhaps the week-long debate, which, as many observers noted, was peculiarly German both in its tone and in its intensity, reflected a realisation that the silly claims of a self-obsessed old man have provided a glimpse of something unpalatable that has no place in how the new Germany likes to be seen by the rest of the world. Today’s Germans have tried hard – building memorials, prosecuting war criminals and paying restitution to former slave labourers – to prove that they have nothing to do with yesterday’s Germans; yet the past tends to catch up with them. Günter Grass seems to have been only too aware of the past’s propensity to insert itself uninvited into the present. “History,” he wrote in his 2002 novel Im Krebsgang, published in English as Crabwalk, “or, to be more precise, the history we Germans have repeatedly mucked up, is a clogged toilet. We flush and flush, but the shit keeps rising.” •