There is perhaps no better place to get close to the Peasants’ War and its reverberations than Bad Frankenhausen, a spa town of 10,000 people on the southern slope of the Kyffhäuser Mountains in northern Thuringia. It was here the insurgents suffered one of their most decisive defeats. On 15 May 1525, on a hill above the town, thousands of armed peasants and their supporters faced the combined armies of the rulers of Saxony, Hesse and Brunswick.

As they had done elsewhere, the rebels initiated negotiations with their adversaries. “We proclaim Jesus Christ,” they wrote to the princes. “We are not here to harm anyone (John 2) but to maintain godly justice. We are also not here to shed blood. If you will do the same, we will do nothing to you.” They had been emboldened by a portent. A rainbow resembling the one on some of their banners had appeared: according to the Book of Genesis, “the token of the covenant” between God and His people.

While the insurgents waited for a reply, the princes attacked them with canons and cavalry. Possibly 6000 rebels were killed, and half of the 600 who were taken prisoner were beheaded the next day.

These events are referred to in Germany as the Schlacht bei Frankenhausen (“Battle of Frankenhausen”), which is surely a misnomer for such a one-sided affair. But perhaps Schlacht in this context echoes the pre-sixteenth-century Middle High German term slaht, which has been preserved in the English “slaughter.” The forces of the peasants were no match for armies of trained soldiers, some of them mounted, all of them supported by artillery.

The “battle” site is still called Schlachtberg, or Battle Mountain. The steeply descending path to Frankenhausen — the route along which those who survived the slaughter tried to escape — is known as Blutrinne (Blood Gully). Standing on the hill, I imagine the insurgents watching the enemy troops approaching, being taken by surprise when the artillery opened fire, panicking and fleeing towards the nearby town, and being massacred by their pursuers. From my vantage point on Schlachtberg, the 500-year distance from the historical event has suddenly shrunk.

From afar, the Schlachtberg is easily recognised by the large cylindrical gasometer-like building at its summit, which houses a panoramic oil painting, 14 by 123 metres, which tourist brochures advertise as the “Sixtina of the North.” Commissioned by the German Democratic Republic’s culture ministry in 1976, this vast artwork is actually more than three times the size of Michelangelo’s frescoes on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

The East German authorities wanted the Schlacht depicted in the style of the battle panoramas popular in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Prominent surviving examples include Michael Zeno Diemer’s monumental depiction of the 1809 Battles of Bergisel in Austria and Louis Dumoulin’s 1912 painting of the Battle of Waterloo in Belgium. The authorities were particularly fond of Franz Roubaud’s 1911 painting of the Battle of Borodino, which is housed in Moscow’s Panorama Museum.

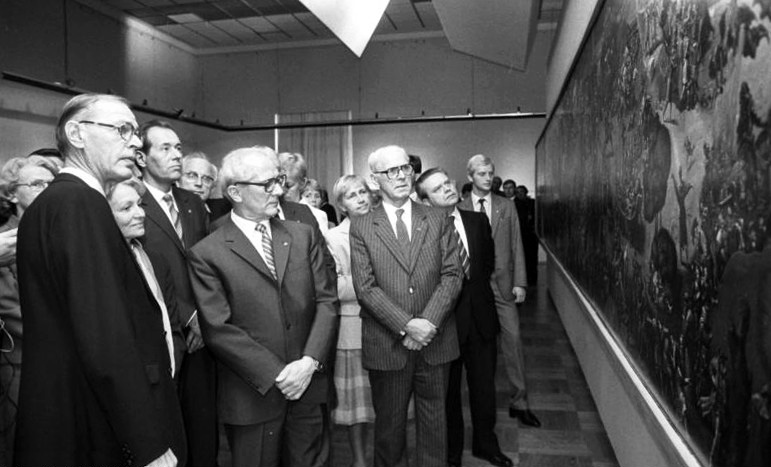

The ministry approached well-known Leipzig artist Werner Tübke, who accepted the commission but warned he would want to do more than merely depict an historical event, and definitely wouldn’t try to emulate Roubaud’s work. He also stipulated that the ministry not interfere in his decision-making as an artist. Between 1979 and 1981, he completed a 1:10 scale model on five wooden panels, which was approved despite some reservations. But tensions remained: at one stage, the ministry arranged for artists from the Soviet Union to complete the job, at another Tübke threatened to leave the GDR for West Germany.

Tübke’s war: the artist (left) showing his scale model to the East German leadership in October 1982. Klaus Franke/Bundesarchiv Bild via Wikimedia

With the help of a small team of collaborators and around 90,000 tubes of paint, Tübke completed the painting in 1987. It was eventually unveiled in September 1989, less than two months before the fall of the Berlin Wall. The most apparent trace of the East German leaders’ intentions is the painting’s title, Early Bourgeois Revolution in Germany. The Soviet Union’s main contribution was the canvas, which had been woven in one piece at a factory in Russia.

Tübke’s painting is by no means socialist-realist. Inspired by the iconography of late medieval and early modern Germany, it also contains allegorical and surrealist elements; tellingly, Tübke considered Giorgio de Chirico, co-founder of the scuola metafisica movement, to be the most important artist of the twentieth century. Tübke also travelled to the Vatican in 1985 to study Michelangelo’s frescoes in order to “add fresh blood to the whole thing,” as he put it at the time.

Many of the panorama’s 3000-plus figures are based on fifteenth- and sixteenth-century paintings, drawings, engravings, woodcuts or sculptures, some of them anonymous illustrations in pamphlets, others the works of well-known artists such as Albrecht Dürer, Pieter Bruegel, Hieronymus Bosch and Lucas Cranach the Elder. While the painting depicts some recognisable historical figures — Martin Luther, Charles V, Erasmus of Rotterdam and Tilman Riemenschneider among them — most of the women and men are unidentifiable. Particularly prominent are the “fools” who appear in several of the scenes.

Two years before the painting’s completion, Tübke said its “intellectual and emotional richness” would reveal itself to viewers if they were prepared not to think of it as a didactic depiction of history. Not unlike the Sistine Chapel frescoes, this monumental painting invites us to let our eyes and minds wander from scene to scene. And yes, the painting does depict the violence of the Battle of Frankenhausen, but that event is embedded in a magical representation of the universe of early sixteenth-century women and men.

Arguably the first harbinger of the 1525 conflict appeared half a century earlier in Niklashausen in Germany’s south. There, a vision of the Virgin Mary told a shepherd that Jesus wanted all “tolls, levies, forced labour, exactions, payments and aids required of the prelates, princes and nobles” immediately abolished. Thousands flocked to hear the man who came to be known as the “Drummer of Niklashausen” talk about his vision. When the local bishop had him arrested, a crowd of some 16,000 people tried to force his release. Soldiers opened fire, killing many of them. The shepherd was burnt as a heretic.

Revolts broke out in other parts of southern Germany in the 1490s and early 1500s. These “Bundschuh rebellions” were named after the boot typically worn by peasants, which was depicted on the rebels’ banner. One of their leaders, Joß Fritz, managed to evade the authorities and initiate revolts in different places over a long period. But it was not until early 1525 that armed unrest engulfed most of southern and central Germany.

The German Peasants’ War wasn’t the result of a worsening economic situation. By and large, the peasantry was better off than in the century before, although they may have begged to differ. True, they had good reason to complain about the lords’ excessive demands on their labour and produce. But the transformation of complaints and legal challenges into armed rebellion has more to do with people’s changing outlook on the world.

The war was not least a result of the Protestant Reformation. In 1517, Luther had published his Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences, later known as the Ninety-five Theses, in which he denounced the Catholic clergy’s sale of indulgences to raise funds for the construction of St Peter’s in Rome. Three years later, in On the Freedom of a Christian, he proclaimed: “A Christian man is the most free lord of all, and subject to none. A Christian man is the most dutiful servant of all, and subject to every one.” The following year Luther was summoned to appear before the Diet in Worms, where he refused to recant. News of his steadfast criticism of the Papacy, and seemingly of serfdom, circulated widely, made possible by Johannes Gutenberg’s invention in the 1450s of a printing press using movable type.

A widespread expectation of impending doom added to a collective sense of nervous excitement. A Great Conjunction — the coming together of Saturn and Jupiter in the night sky — occurred on 30 January 1524, and Venus, Mercury, Mars, Saturn and Jupiter were all in the sign of Pisces between 13 and 19 February. Astrologers’ claims that these unusual celestial phenomena foretold wars, poor harvests and floods, circulated widely in pamphlets.

Piscean prophecy: title page illustration for Leonhard Reymann’s Practica on the Great and Middling Conjunction of the Planets, published in Nuremberg in 1523. Erhard Schön/Wikimedia

When the peasants rose up in different parts of Germany in the spring of 1525, it seemed like a concerted attack on the existing order. Though similar, their complaints also reflected local circumstances. They nearly always demanded the right to appoint their own pastors, the abolition or reduction of tithes, levies and taxes, and the freedom to hunt and fish. Many but not all of the rebels were serfs whose bodies were owned by their lords. Some were comparatively wealthy, others were poor day-labourers. In some regions, villagers were supported by townspeople; in Tyrol, peasants and miners formed an alliance. Even some nobles — including Götz von Berlichingen, the main protagonist of the eponymous 1773 play that made Johann Wolfgang von Goethe famous — sided with the peasants.

Even in the spring and summer of 1525, when hostilities peaked, there was not one war, but many bloody local or regional conflicts in which the peasants targeted particular monasteries and castles and challenged the authority of abbots, bishops and princes. This fragmentation also reflected political divisions within Germany. From 1519, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, head of the House of Habsburg, reigned over the German lands (as well as much of Italy, the Low Countries, Spain and other parts of Central Europe). But while the Habsburgs had possessions in Austria and southwestern Germany, elsewhere Charles’s German empire was a patchwork of territories ruled by princes, bishops and cities, each of them in pursuit of their own interests.

The complex and sometimes confusing history of the German Peasants’ War is magnificently told in Australian historian Lyndal Roper’s recently published Summer of Fire and Blood. Her previous books have dealt with women in sixteenth-century Germany, witchcraft and, in an acclaimed biography, Martin Luther. Roper is not only exceptionally knowledgeable about early modern Germany’s cultural history, she is also a terrific storyteller. The further I delved into her book, the harder I found it to put it down.

Historians writing about 1525 have to grapple with a lack of historical sources to help flesh out the insurgents’ perspective. Peasants didn’t leave behind first-hand accounts — in fact, nearly all of them were illiterate. Much of what we know about their motivations has been gleaned from their enemies’ words or from statements they made when interrogated, often while being tortured. The sources produced by victors and rulers can be read against the grain, but only within obvious limits.

In his 1992 book about the Drummer of Niklashausen, the American historian Richard Wunderli employed fictional elements — always clearly signposted — to make up for the lack of primary sources and draw attention to the inadequacy of the historical record. Roper takes a different path, highlighting the biases of the written accounts, drawing heavily on contemporary visual sources, and focusing less on individual actions than on collective mentalities, emotions and worldviews. She also relies on her readers’ ability to imagine ordinary people as historical actors, and it is this that makes her book so exciting. Without claiming to do justice to her extraordinarily rich account, I will highlight those of Roper’s insights I found particularly fascinating.

Significantly, the rebels swore oaths that turned them into brothers. “Once sworn, that bond of fraternity was lived out in drinking, eating, sleeping, and marching together,” Roper writes. Peasants from a local area or region formed a Haufen, which Roper translates as “band.” The German term, which literally means “heap” or “pile,” conveys a sense of disorderliness, but the various Haufen usually followed a democratically elected leader. They were also remarkably disciplined: Roper found no evidence that they committed rapes.

The movement of these Haufen of previously unrelated “brothers” through unfamiliar terrain brought the men together. “The thrill of it must itself have helped drive them on,” Roper observes. “They felt what it was to be ‘free.’” Brotherhood was offered to — and sometimes accepted gratefully or grudgingly by — miners, townsfolk and even lords and monks. “It was also an emotional appeal, an attempt to lance the potential aggression by offering kinship and love,” Roper explains. “Brotherly love was about creating a Christian world where there would be no division, class or enmity, and where injustice would be overturned by the affective bond of fraternity.”

Roper’s attention to gender issues subverts a romantic reading of the rebels’ fraternity. She goes to great lengths to shed light on the role women might have played in the war, without unduly focusing on a handful of prominent individuals, such as Ottilie von Gersen or Margareta Renner, as some of the current exhibitions to mark the quincentenary do.

Roper emphasises the role of emotions, which she claims have too often been ignored in accounts of the conflict. Thus the peasants’ preparedness to keep going, even after the first reports of the revenge exacted by the lords had reached them, may have partly reflected the elation they were experiencing.

“We know with hindsight that their actions were doomed to fail, but they did not know that,” Roper writes. The dubious benefit of hindsight has persuaded many historians to focus on the defeat and ignore how, at least for a few months, the peasants were remarkably successful, taking control of large swathes of southern and central Germany and beginning to “put plans for a new future into action.” Roper shows how the pillaging of monasteries meant that the peasants gained access to significant resources and were thus able to provision Haufen of several thousand men. To ignore that success would be to ignore how it came about.

Roper debunks the claim, promoted in a couple of the exhibitions I’ve seen in recent months, that the peasants attacked armies of heavily armed and experienced soldiers with nothing more than pitchforks. They had some artillery, they were joined by men who had worked as mercenaries, their military strategies often worked, they were skilful negotiators, and they knew how to get what they wanted through intimidation alone.

Summer of Fire and Blood is a rehabilitation of early modern peasants as smart and thoughtful historical actors. As Roper writes, they are “the heroes” of her book.

Was the German Peasants’ War historically significant? Roper certainly thinks so. She argues that the war altered the course of the Reformation, suppressing its potential to bring about profound social change. Luther, who had seemed sympathetic at first, turned against the peasants and insisted that the traditional order and the authority of state and church be upheld. He also justified the slaughter by calling on his readers to “smite, slay and stab” the rebels and proclaiming such killings godly work. I doubt whether the readiness with which the Lutheran clergy in Germany, with few exceptions, embraced first the authoritarianism of Wilhelmine Germany, and then fascism, could be explained without going back to the 1520s.

Roper also shows how the war weakened monasticism. Hundreds of monasteries and convents were ransacked and some of them burnt to the ground. Then, after the war, Protestant rulers exploited the monastic orders’ weakness and secularised some of those that had survived.

The conflict’s demographic impact was profound. As many as 100,000 peasants were killed. In the areas directly affected by the war, perhaps 15 per cent of the men capable of bearing arms — those in the best position to do the hard physical labour on which rural communities relied — lost their lives.

According to Roper, some of the ideas developed by the insurgents lingered beyond their comprehensive defeat. She is particularly interested in a 1525 pamphlet, To the Assembly of the Common Peasantry, whose anonymous author “supplies a potted history of the tyrants of Roman history.” Subsequently, she observes, the “concept of tyranny found its way from radical religion and political utopianism into nascent republicanism.”

She believes that “the peasant conception of freedom” and their “utopian vision” is still relevant. “It encompassed the environment and the obligations of care we owe to others, our mutual dependence… They did not think in terms of individual rights.”

Roper suggests the German Peasants’ War ought to be termed a “revolution” because of the transformations it wrought and the number of people it affected. I wish she had elaborated, if only because the question of which historical events and processes in German history amounted to a revolution often comes up in public debate. Could it be that the Peasants’ War — “the most radical fact of German history” (Karl Marx) — was the only revolution Germany ever had?

In postwar West Germany, the Peasants’ War has been considered historically significant mainly because of the Twelve Articles, a list of demands formulated in March 1525 by the furrier Sebastian Lotzer in the southern German town of Memmingen. Based on numerous lists of local complaints, Lotzer’s articles “allowed everyone to recognise their own concerns: peasants free and unfree, townsfolk… and miners,” Roper writes. “Written in rhythmic, memorable prose, the demands sounded biblical, and there were twelve of them, like the Twelve Apostles; indeed the document reads at points almost like a devotional creed.”

The Twelve Articles were reproduced repeatedly and distributed widely; many of the 25,000 printed copies would have been read out publicly and discussed in villages and towns. Although similar texts appeared, only the Twelve Articles became known all over central and southern Germany, thereby helping to turn numerous local conflicts into the Peasants’ War.

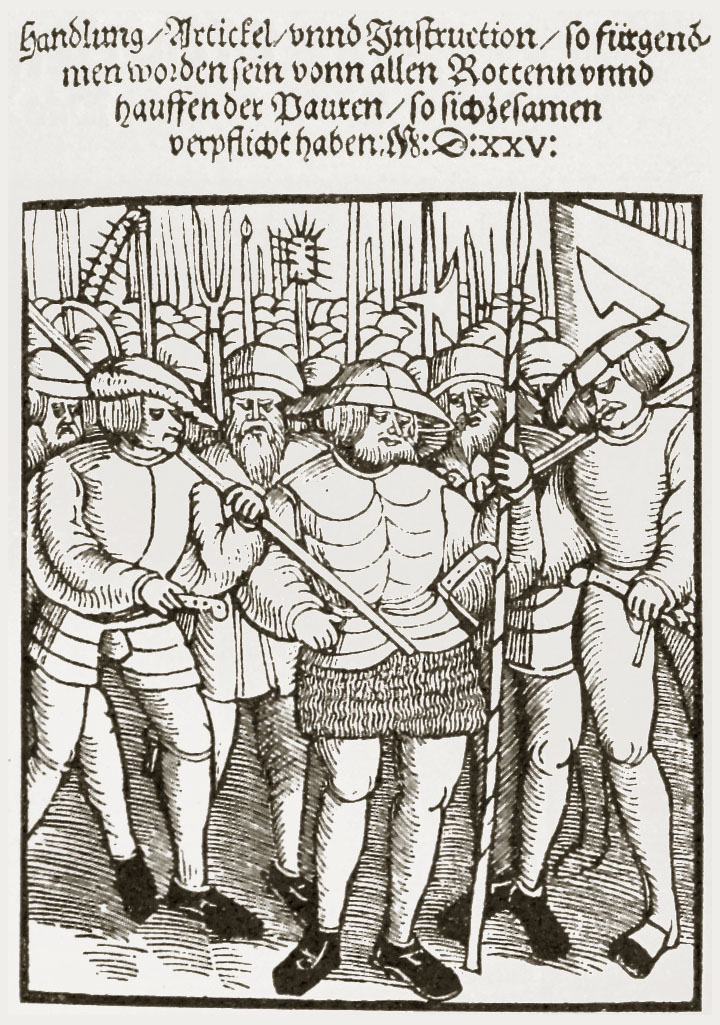

Contested inheritance: an anonymous artist’s woodcut on the title page of one of numerous editions of the Twelve Articles published in spring 1525. Wikimedia

In March this year, speaking on the Twelve Articles’ quincentenary, German president Frank-Walter Steinmeier insisted that they “were not a footnote in Germany history” but “triggered a movement for freedom that spread like wildfire throughout southern and central Germany.” Memmingen, he claimed, “was the starting point of a mass uprising for freedom and justice.” Maybe Roper’s German publisher agrees, because the German edition of her book, published months before the English original, includes the original text of the Twelve Articles and a rendering into today’s German.

According to Steinmeier, the ideas first formulated in the Twelve Articles were taken up another three times: during the 1848 Revolution, by the drafters of the West German constitution, and in 1989 when the “brave women and men in Plauen, Leipzig, East-Berlin and many other places fought for freedom.” “Remembering the places, actors, ideas and events in our history of freedom is more important than ever in these turbulent times,” Steinmeier said. “[L]iberal democracy is being threatened and attacked — both internally and externally, and with a force many of us would never have imagined.”

In a thinly veiled reference to the far-right Alternative for Germany, or AfD, the president warned: “At the same time, we are witnessing that those who invoke historical freedom movements are precisely those who incite hatred against democratic institutions and want to allow freedom to apply only to themselves and their peers.” Leaders of the AfD have indeed tried to style themselves as the legitimate heirs of the March revolutionaries of 1848 (and demanded that 18 March, the day soldiers opened fire on demonstrators in Berlin, be declared a national day of remembrance). They have also embraced the failed Hitler assassin Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg and have claimed to act in the tradition of the demonstrators who brought about the fall of the East German regime.

Twelve Articles for today: German president Frank-Walter Steinmeier speaking in Memmingen’s St Martin’s Church on 15 March at a commemoration of the quincentenary of the Twelve Articles. Stefan Puchner/dpa via Alamy

The Social Democrat Steinmeier is not the first German head of state to commemorate the publication of the Twelve Articles in Memmingen. In 2000, Johannes Rau, another Social Democrat, marked the 475th anniversary by insisting that the authors of the Twelve Articles are part of a tradition stretching from Amos to Martin Luther King and from Dietrich Bonhoeffer to the East Timorese bishop Carlos Belo. In 2009, Rau’s immediate successor, Christian Democrat Horst Köhler, referred to the Twelve Articles in a speech lauding the writer and former East German dissident Reiner Kunze, recipient of the Memmingen Freedom Prize 1525. Köhler, too, referred to the eighth-century BC prophet Amos, and like Steinmeier and Rau declared the Twelve Articles to be a kind of human rights charter.

Köhler drew another historical parallel: the sixteenth-century peasants who fought for freedom were “persecuted, imprisoned, and killed,” much like members of the resistance in Nazi Germany and “those who fought for freedom in the first workers’ and peasants’ state on German soil,” using the German Democratic Republic’s official designation.

Comparisons and parallels, often questionable, are also a feature of exhibitions marking the quincentenary. The Württemberg State Museum in Stuttgart currently hosts an exhibition, “Protest! From Rage to Movement,” ostensibly commemorating the Peasants’ War. The curators have drawn a line from the protests of 1525 to those of 2020, when tens of thousands of people in Stuttgart demonstrated against the measures designed to stop the spreading of Covid-19, and invite visitors to vent their own fury by taking a baseball bat to a car.

In 1525, insurgents looted Kloster Veßra, a Premonstratensian abbey in the south of Thuringia. Unlike other monasteries, it was not destroyed then, but burned down accidentally in 1939. Today it is an open-air museum. An exhibition mounted this year features video footage of protests by German farmers in the winter of 2023–24 prompted by the federal government’s decision to cut fuel subsidies, as if the expectation that farmers pay more for their diesel is comparable with the rapacious demands made of sixteenth-century serfs.

Lyndal Roper is not the first to call the Peasants’ War a revolution. “Both at home and abroad no one has ever paid enough attention to the fact that there was once a German revolution,” wrote Hugo Ball, founder of the Dada movement, in his 1919 Critique of the German Intelligentsia with reference to the Peasants’ War. That’s still true. Yet Germans readily apply the term to the protests of March 1848 and September–October 1989, and the abdication of Wilhelm II in November 1918.

The attention the conflict has received has also been very selective. Steinmeier celebrated the Twelve Articles in Memmingen in March but didn’t visit Bad Frankenhausen on 15 May this year, nor any other site where thousands of insurgents were massacred 500 years ago. The quincentenary has prompted commemorations only locally, particularly in Thuringia and Baden-Württemberg.

The lack of national attention becomes particularly obvious when the quincentenary of the Peasants’ War is contrasted with the 500th anniversary of the Reformation. Between 2008 and 2017, Germany marked the latter with the Luther Decade, a ten-year long celebration of Martin Luther’s role in German history. More than a thousand events commemorated the birth of Protestantism during the Reformationsjubiläum, the year-long jubilee held in 2016–17. The thirty-first of October 2017, the anniversary of the day Martin Luther reputedly nailed a copy of his Ninety-five Theses to the doors of All Saints’ Church in Wittenberg, was declared a national holiday.

Afterwards, the state parliaments of the North German (and predominantly Protestant) states of Hamburg, Bremen, Lower Saxony and Schleswig-Holstein made 31 October a permanent public holiday, thereby emulating the five East German states that had instituted a Reformation Day public holiday in the early 1990s.

I can’t recall learning about the Peasants’ War in high school, but I distinctly remember the attention our history teacher paid to Luther’s achievements and the Protestant armies’ fortunes in the Thirty Years’ War of 1618–48. West German friends of my age all report that they found out about the peasants’ uprising only after finishing school.

But when I dug out my old history textbook, published in 1966, it turned out my suspicion that the Peasants’ War is not mentioned was unfounded. Maybe we just took too long to get through the eleven pages devoted to Luther and had to skip the four pages on “Unrest in Germany.” (Half of that text, by the way, is concerned with Luther’s role in the war. It is illustrated with two woodcuts depicting insurgent peasants, and portraits of two knights, Ulrich von Hutten and Franz von Sickingen, and of Luther’s collaborator Philip Melanchthon.)

The early modern rebels I first came across were not the peasants of 1525, but Joß Fritz and the Bundschuh. That was in the second half of the 1970s, in the early days of the anti-nuclear movement, when opponents of a planned nuclear power station at Whyl in the southwest of Germany (and, a few years later, of a Mercedes test circuit) publicly identified with the Bundschuh and flew its flag.

My old textbook’s chapter on the 1525 “unrest” includes the lines: “In Thuringia, a revolutionary movement emerged under Pastor Thomas Müntzer. He wanted Christianity without the Church, a state without authority. Thus, the Kingdom of God was to be established on earth.” That’s the only reference to Müntzer. There is no image of him, yet Luther is pictured three times.

In the historiography of the Peasants’ War, Thomas Müntzer (sometimes also spelled Münzer) — radical theologian and charismatic preacher, dreamer and firebrand, bête noire of Luther and the princes — is usually considered a key protagonist. But assessments of his role and impact have differed widely.

If I had attended school in the German Democratic Republic I would have learned about Müntzer. I would even have thought I knew his face, because it was depicted on the East German five-mark note. But Müntzer might not have looked anything like that image; his earliest known depiction is a copperplate engraving from much later, in the early seventeenth century.

If I had grown up in East Germany, I might also have associated Müntzer’s face with that of Wolfgang Stumpf, the actor cast as Müntzer in Martin Hellberg’s film Thomas Müntzer, produced in 1956 by the state-owned DEFA. The film was frequently shown in East Germany but reached West German audiences only after 1990.

Among the East German representations of Müntzer, Tübke’s is the odd one out. Müntzer appears twice in his painting, once as a preacher and once in the scenes of the Battle of Frankenhausen that are reproduced at the beginning of this essay. There he cuts a forlorn figure: not leading the charge against the princes’ armies but resigned, indifferent to the drummer next to him, a Bundschuh banner lying at his feet.

Refracted by history: members of the Freunde von Anno Dazumal association in May this year reenacting the 1525 march of 300 Mühlhausen townsfolk, led by Thomas Müntzer, to join the rebels encamped outside Frankenhausen. dpa picture alliance/Alamy

West German interpretations of the past came to dominate representations of the Peasants’ War in reunified Germany. Of the three presidents commemorating the Peasants’ War after 1990, only Rau mentioned Müntzer — and only when he talked about the East German regime’s abuse of history. The exhibitions I visited in Thuringia in recent weeks give the impression that their curators wanted to avoid drawing attention to Müntzer’s role.

Roper doesn’t seem to think much of Müntzer. His theology, she finds, “was at once majestic in its apocalypticism and modest in scope,” his rhetoric “a flood of bloodthirsty, violent language with barely a pause for breath.” But she also acknowledges that most of what we know about him is “refracted through the lenses of his opponents or of those who desperately tried later to distance themselves from him.” She also makes the important point that “peasant theology,” of which her book provides valuable glimpses, was very different from Müntzer’s (or from Luther’s for that matter).

Two towns in East German Saxony-Anhalt carry Luther’s name: Lutherstadt Wittenberg (since 1938), where he published his Ninety-five Theses and translated the Bible, and Lutherstadt Eisleben (since 1946), where he was born and died. Mühlhausen, where Müntzer worked as a preacher and was executed, was awarded the title Thomas-Müntzer-Stadt in 1975; Stolberg, where he was born, was named after him in 1989. In the case of the latter two towns, which are also in East Germany, the additional names were dropped after 1990.

No town is named after events or protagonists in the Peasants’ War. Frankenhausen, where the “battle” of 15 May 1525 was fought, is officially known as Bad Frankenhausen/Kyffhäuser. The town was registered as a spa (Bad) in 1927; it is one of fourteen certified spa towns in Thuringia. “Kyffhäuser” refers to the nearby mountains and helps to distinguish the town from other Frankenhausens, such as a village in Hesse. But for many visitors Kyffhäuser signifies the Kyffhäuser monument rather than the mountains.

Legend has it that a medieval emperor — initially Frederick II (1194–1250), but from the nineteenth century his grandfather Frederick I (1122–1190), known as Barbarossa in Germany — is asleep in a cave deep inside the Kyffhäuser mountains, biding his time until the ravens stop circling the mountains, when he will rise and lead a united Germany back to its erstwhile glory. In 1816, the Grimm brothers published the legend of Frederick Red Beard in their compilation of German legends. The following year, the German poet Friedrich Rückert identified the historical figure of Barbarossa as the subject of the legend in a well-known poem: “The splendour of the Empire / He took with him away; / And back to earth will bring it / When dawns the promised day.”

Waiting for the ravens to stop circling: Barbarossa at the base of the Kyffhäuser monument. Klaus Neumann

After the unification of Germany in 1871, the Hohenzollern emperor tried to position himself as the legitimate heir or reincarnation of the Hohenstaufen Barbarossa. In 1896, an eighty-one-metre-high monument with a statue of Wilhelm I at the top, funded entirely through donations mainly from veterans of the 1870–71 Franco-German war, was erected in the ruins of a medieval castle, Reichsburg Kyffhausen, in the northeast of the mountains.

After the first world war, the monument was used to invoke the revanchist “Kyffhäuser spirit” and continued to be a rallying point for the veterans’ associations. It survived the second world war and the forty years of the German Democratic Republic. In 1964, the East German authorities even added to a dome-like room inside the monument a bronze relief that depicts scenes from German history.

But that was a rather half-hearted attempt at repurposing the Kyffhäuser monument. The East German leadership’s response to a monument proclaiming a line of descent from medieval Barbarossa to the nineteenth-century Hohenzollern emperors was to commission Tübke to create an image suitable for a counter-genealogy.

The Kyffhäuser monument is only a two-and-a-half-hour walk from Schlachtberg. When I visited last month, it seemed to be a more popular destination than the panorama museum. But tourist numbers are no longer as high as in 1990, when West Germans were first able to freely visit the East. Much like earlier generations, they were attracted by the monument’s purported role as a symbol of the German nation, rather than by its scenic location.

Between 2015 and 2019, members of the most extremist faction of the far-right AfD, led by Thuringia’s Björn Höcke, chose the myth-laden Kyffhäuser mountains for their annual gatherings. Höcke himself is convinced that “Germans’ longing for a historical figure to heal the nation’s wounds, overcome its divisions and set things straight, is deeply embedded in [their] soul.”

The Kyffhäuser myth resonates with the AfD and its followers because it sees the present as deficient and anticipates the return to a past where those deficiencies will be overcome. Frederick I is also a suitable foil because he died in the Middle East while leading an army in the Third Crusade; after all, the AfD, too, has embarked on its very own crusade against people of the Muslim faith.

The panorama museum never played the role envisaged by East Germany’s communist leaders, partly because of Tübke’s peculiar interpretation of his commission and partly because the regime collapsed within weeks of the museum’s opening. So far, reunified Germany’s political leaders don’t appear to be interested in embracing the building on top of Schlachtenberg in order to neutralise the nearby relic of Wilhelmine militarism.

It wasn’t the German Democratic Republic that discovered Thomas Müntzer. He had already played a prominent role in Wilhelm Zimmermann’s three-volume history of the Peasants’ War, which was published in the early 1840s and informed Friedrich Engels’s 1850 text about the war. Hugo Ball, who lamented Germans’ lack of attention to the Peasants’ War, called Müntzer a “philosopher, prophet and rebel” and considered him the “leader of the German peasants’ revolution.”

In notes dated 18 November 1917, and later published in his book Flight out of Time: A Dada Diary, Ball wrote: “I am now often meeting with a utopian friend, E.B., who prompts me to read [Thomas] Morus and [Tommaso] Campanella, while he in turn is studying Münzer.” The friend was the Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch, later an inspiration for sections of the student movement of the late 1960s, and best known outside Germany for his The Principle of Hope.

Bloch published the fruits of his studies in Thomas Münzer als Theologe der Revolution (1921) and it was there that I first encountered the sixteenth-century theologian. When I came across it as an undergraduate student, the book was a revelation — and an antidote to the tedious history seminars and lectures I attended.

Rereading the book several decades later, I wonder how much of the text’s expressionist prose I comprehended at the time. Now I am critical of Bloch’s interpretation of the Peasants’ War and his elevation of Müntzer as its key protagonist. He makes the peasants’ self-interest, naiveté and political fragmentation responsible for their defeat and seems to think that the outcome would have been different if only the miners had joined the fight. Although his historical materialism is far more sophisticated than that of Marx and Engels, the book’s historical account now strikes me as doctrinaire. I don’t hold it against Roper that she didn’t include Bloch’s book in her bibliography.

But there are parts of his text that I still cherish. He insists that the 1525 insurgents and Müntzer speak to us. That’s not because we are able to drink Bauernbräu, a craft beer created to commemorate the Peasants’ War, or experience the “atmosphere and excitement” of a reenactment of the slaughter on Schlachtberg. It’s not because we ought to be reminded of them when we think about the drafting of the West German Constitution, Swabian Covid-19 conspiracy theorists or farmers protesting against the cutting of fuel subsidies. It’s because their dreams and deeds constitute a promise yet to be fulfilled.

Historians tend to privilege pasts that can be regarded as antecedents of the present and dismiss the presumed cul-de-sacs of history. The dreams and deeds of hundreds of thousands of early modern peasants constitute such a cul-de-sac. True, some of their ideas lived on, for example among sixteenth-century Anabaptists. But the survival of dreams and deeds should not be needed to justify learning about them. Perhaps Lyndal Roper, too, had in mind dreams and deeds cut short when she referred to “this freighted history” and the “paths that were not taken.”

What’s lacking these days in many Western political cultures is the ability to dream radically, to develop visions for a tomorrow that is more than an extension of today. Pasts that are, in William Faulkner’s words, not even past yet, and past injustices that are not abgeschlossen (done with) in Walter Benjamin’s sense, could animate such visions, particularly when the just world envisaged by a previous generation has not yet been realised.

On 27 May, exactly 500 years after Müntzer’s death, “Am jüngsten Tag – eine Abrechnung” (On Judgement Day – A Settling of Accounts) by Vicki Spindler premiered in the Frankenhausen panorama museum. In this remarkable play, Müntzer, his wife Ottilie von Gersen and Luther meet in 2025. While Luther is pleased about today’s world, Müntzer insists that the quincentenary commemorates a 500-year nightmare. To truly achieve freedom and justice, Spindler lets him say, people need to become each other’s and the world’s friends and guardians; everything would be possible if only they stopped being egotistical.

Bloch and, a few years later, Benjamin called the attention to the unfinished business of the past: Eingedenken. The term is usually translated as “remembrance” or “recollection” (as neologisms work not nearly as well in English as in German, I leave it at that). Eingedenken is keenly interested in the redemption of buried promises, but it is the exact opposite of the far-right Kyffhäuser pilgrims’ regressive turning back, their longing for a return to the authoritarianism of Wilhelmine Germany or to the crusading days of medieval Europe.

In fact, in the quincentennial year, Eingedenken could be a response prompted by attempts either to resurrect the dream of a thousand-year Reich, or to paper over an unresolved injustice by claiming, as Spindler’s Luther does, that all is well.

Müntzer’s millenarian fervour struck a chord with Bloch. He emphatically denied looking back. “The dead come back,” he wrote in the introduction of his book, and he would enable them to continue where they left off. Müntzer was Bloch’s personal drummer, urging him on, the events of 1525 the revolution’s “underground history” that needed to be reanimated. Eingedenken in this sense means seizing the past by the scruff of its neck.

But Eingedenken is also contemplation — in this case, of a defeat that could hardly have been more devastating. The author of the pamphlet To the Assembly of the Common Peasantry had warned: “Listen dear brothers, you have embittered the hearts of your lords so greatly with an excess of gall that they will never be sweetened again… There will be less pity shown you than any evildoer or murderer.” He was right. Tens of thousands were slaughtered by the princes’ soldiers. Those taken prisoners were sometimes tortured before being killed. The executions were horrific spectacles to intimidate the survivors. Some of those whose lives had been spared were branded or blinded or had their fingers chopped off.

Müntzer too met a horrible end. He escaped to Frankenhausen only to be tracked down, tortured for several days and then beheaded. His head was put on a spike and, like the rest of his body, left to rot.

To publicly remember the vanquished — not as heroes, but as men and women who deserved so much better — is one way of doing justice to them. No contemporary memorials honoured the defeated rebels in sixteenth-century Germany. But a design of such a memorial survived. Albrecht Dürer, the most famous German artist of that time, sketched a monument that features a sad-looking peasant who resembles the angel in Dürer’s 1514 engraving Melencolia I, but is sitting atop a pillar, a sword stuck in his back.

Unperturbed? Timm Kregel’s Dürer-inspired sculpture in Mühlhausen. Eckart Wetzel

In 1986, Canadian artist Jeff Wall produced a work he named The Thinker. The title is a reference to Auguste Rodin but the figure pictured by Wall with the sword in his back is inspired by Dürer’s sketch. Two recent memorials in Germany also attempt to realise Dürer’s design: Peter Brauchle’s 2002 bronze sculpture at Nußdorf, which recreates only the figure atop Dürer’s column, and an arresting seven-metre high bronze sculpture by Timm Kregel in Mühlhausen, unveiled in April — without any input from the German head of state.

Kregel’s sculpture commemorates the peasants’ defeat. But the figure atop the column seems unperturbed by the sword — as if to say: “I’m not done yet.” •

Summer of Fire and Blood: The German Peasants’ War

By Lyndal Roper | John Murray | $75 | 527 pages