In May 1972, six months before that year’s election, the editor of the Melbourne Age enjoyed a surreal lunch with prime minister Billy McMahon. Describing him as “really dazzling company,” Graham Perkin was nonetheless staggered by the prime minister’s summary of the political scene and his government’s future.

“The funny little man,” Perkin told a colleague, “has convinced himself that he is a brilliant success and sees himself winning handsomely in November and remaking the nation in the following three years; leading them” — the Coalition — “to victory in 1975, and then retiring with honours thick upon him. God save us all!”

To modern readers, McMahon’s hopes seem as preposterous as they did to Perkin. Most accounts of his government use the same adjectives — incompetent, reactive, hapless, embarrassing — and follow the same line: nothing of consequence was achieved between 1969 and 1972, and the election of the Gough Whitlam–led Labor Party was never in question.

This view has several effects. One is to diminish Labor’s genuine achievement in 1972, when a party scarred by twenty years of discord and electoral failure convinced voters that the vision, policies and leadership Australia needed were to be found among its MPs. Another is to render the years from 1969 to 1972 as a shapeless interregnum between the going of prime minister Robert Menzies and the coming of Gough, an antipodean Dark Ages during which nothing really happened. The last is to leave our understanding of those years profoundly incomplete by failing to take seriously the efforts of the Coalition government to govern during a period of immense change.

While confident of victory, Whitlam always insisted the 1972 campaign was a live contest. And while he was never backward in adducing McMahon’s flaws, he also perceived an opponent more wily than popularly imagined. As prime minister, Whitlam argued, McMahon had tried to “bestride two horses”: “He claimed to be the real heir to Menzies, yet he also claimed to recognise and accept the need for change in a changing world.” And the result? “This balancing act he did with some skill.”

A “balancing act” is one useful way of understanding the Coalition government’s actions during 1969–72, of seeing how it tried relentlessly, first under John Gorton and then under McMahon, to manoeuvre itself into a position where another election victory might be possible.

At a distance, the events following the 1969 election are confounding: the leader of the victorious party was immediately challenged by two of his own ministers.

With the benefit of hindsight, the 1969 election result — which resulted in the Coalition’s loss of sixteen seats — confirmed the waning fortunes of a government in office for two decades. At the time, though, it seemed more like a stern rebuke to prime minister John Gorton. Vaulting him from the Senate into the prime ministership after the unexpected death of Harold Holt, Gorton’s colleagues had elevated him in the belief that he possessed sound and sorely needed political judgement, and that his ability to perform on television would be compelling to voters.

The two years that followed brought both beliefs into question. Gorton’s ambivalence towards some of his colleagues and his tendency to unilateral decision-making antagonised many within the government and increasingly alarmed those outside it. Strong-willed and confident, he rarely backed down: “John Grey Gorton,” he rounded on one impertinent senator, “will bloody well behave precisely as John Grey Gorton bloody well decides he wants to behave!”

After a strong start, moreover, Gorton’s abilities as a public speaker seemed to desert him over the course of 1968–69. Tortuously convoluted prime ministerial statements became so much the norm that Whitlam took to ridiculing Gorton simply by quoting him verbatim. As one famous example ran, “On the other hand, the AMA agrees with us, or, I believe, will agree with us, that it is its policy, and it will be its policy, to inform patients who ask what the common fee is, and what our own fee is, so that a patient will know whether he is to be operated on, if that’s what it is, on the basis of the common fee or not.”

Amid these personal shortcomings were more serious policy disagreements. During the 1969 campaign, Gorton had gestured towards traditional Coalition strengths as well as “new horizons”: alongside hawkish statements on national security and tax cuts, he promised increased spending on education, a new Australian film school, and reforms to healthcare. But his statements about defence did little to assuage suspicious hardliners in his own party and in the avowedly anti-communist Democratic Labor Party, which generally backed the government. And his moves to withdraw Australian troops from Vietnam failed to mollify the anti-war protesters who took to the streets in successive moratorium marches.

Gorton’s domestic policies, meanwhile, many of which included an empowered Commonwealth reaching into matters traditionally the purview of the states, antagonised state premiers and colleagues whose fidelity to federalism was a matter of faith.

All this fed into the leadership challenge launched less than two weeks after the election. While treasurer McMahon and national development minister David Fairbairn failed in their bid to displace Gorton, the fissures their challenge exposed didn’t close over. A ministerial reshuffle to blood a younger generation of MPs — including Malcolm Fraser, Billy Snedden and Andrew Peacock — spurred suggestions of cronyism. Backbenchers attacked government legislation in the privacy of the government party room and the public spaces of the House and Senate.

A poor showing at the half-Senate election, late in 1970, was followed by an unsuccessful party-room motion for Gorton’s resignation; then a murky series of press reports in March 1971 spurred Fraser to resign as defence minister and savage Gorton in the House. A confidence vote on Gorton’s leadership tied; Gorton resigned as prime minister; McMahon was elevated to the top job; and — farcically — Gorton was elected, if only for a short time, to the deputy party leadership. As one reporter exclaimed after the last of these events, “You must be joking.”

The bitterness engendered by these developments lingered. Trust was non-existent, whispers of further leadership spills continued, and policy disagreements were so pronounced that the break-up of the Coalition was even broached. In McMahon, the government had a leader who had done much to sow the seeds of this turmoil and who, in office, would sow more still; but, again in McMahon, it had a politician with twenty years of experience at the highest levels of government who was willing to do all he could to stay in office. As governor-general Paul Hasluck wryly remarked, McMahon would “not be cumbered either by ideals or principles” in pursuing that goal.

McMahon’s at-all-costs attitude surfaced conspicuously when he began shifting and tacking on the question of whether Australia should extend diplomatic recognition to the People’s Republic of China, abandoning its long recognition of the Taiwan-based Republic of China and the fiction that the latter remained the sole, legitimate government of China.

In 1958, as a relatively lowly minister, McMahon had argued that the People’s Republic should not be admitted into the international community until it had renounced the use of violence; as minister for external affairs, in 1970, he agreed that the country could not forever remain on the periphery but insisted on putting conditions on any kind of recognition or engagement. His view was influenced more by domestic political circumstances than any moral or strategic factor: “Remember, please, that we have a DLP,” McMahon told deputy secretary Mick Shann, “and that its reaction must be considered!”

By the time the Gorton cabinet reviewed its relationship with the People’s Republic, in February 1971, its resolution was similarly timid: it accepted that the government in Peking (as Beijing was known) was engaging with the international community and that Australia’s policy of diplomatic recognition would have to be reappraised — but decided that it would, for the moment, follow the lead of the United States.

The consequences of this hesitant ambivalence began to play out a month after McMahon became prime minister, when Whitlam sought an invitation to visit Peking. McMahon attacked him on grounds of naivety for engaging with a government that had not yet renounced violence; then, when Whitlam’s invitation to visit was granted, announced that his government would “explore the possibilities of establishing a dialogue” with Peking.

In the space of a month, McMahon had put his government astride two horses, of opposition and of engagement. He still believed the government to be riding high when Whitlam visited China in July. Criticising the Labor leader for his “instant coffee diplomacy,” he told a gathering of Liberal Party members that China “has been a political asset to the Liberal Party in the past and is likely to remain one in the future.”

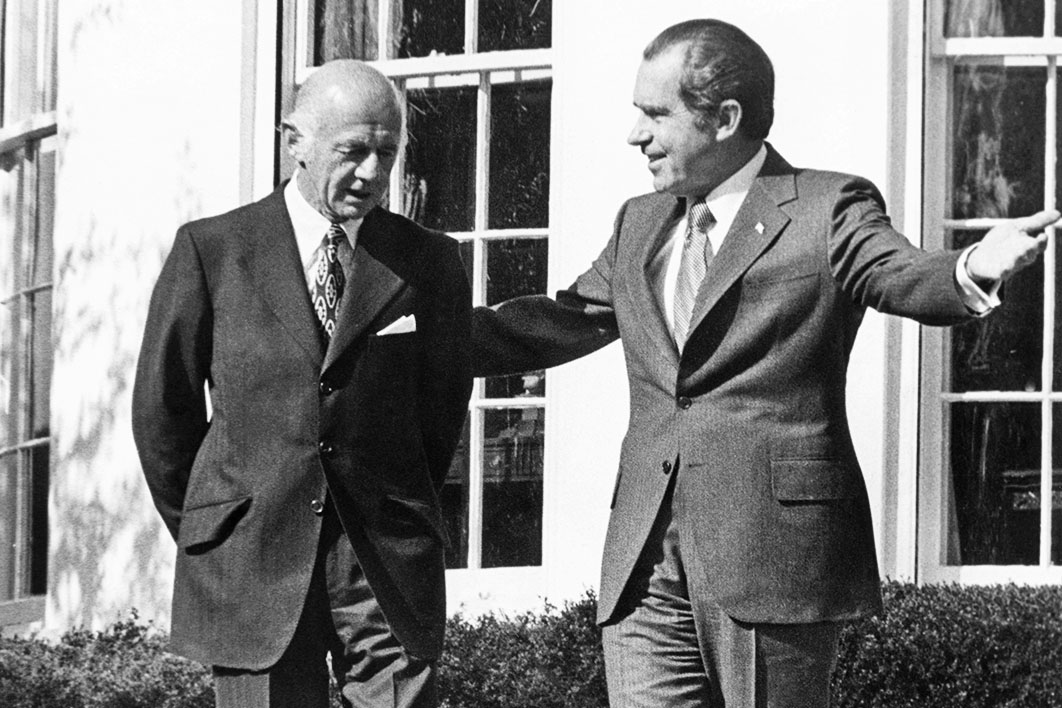

That future was terribly short-lived. Within days of Whitlam’s visit, US president Richard Nixon announced he would visit China the following year. McMahon sputtered. He told the press that “normalising relations with China,” as Nixon was doing, had been his government’s policy all along, but in private he was angry and embarrassed, aghast that he had been so publicly undercut. Lashing out, he sacked his foreign minister and criticised Nixon. In the eyes of the Americans he was “on edge and almost frenzied in trying to stay on top of his job”; to the British, McMahon knew already that he was “not much good in the part” of prime minister.

McMahon eventually conceded that his government had failed on China. He was aware that Whitlam had won considerable plaudits and that he himself had looked a fool. Yet he continued to try to ride the two horses. He explored accompanying Nixon to Peking; he tried to find a halfway point between complete aversion and the diplomatic recognition Whitlam had promised. Rebuffed by the Chinese, he was then rebuked by DLP leader Vince Gair, who denounced the contest over who was more “ahead” on the issue of China. Stung, McMahon refused an invitation for army minister Andrew Peacock to visit China as part of an unofficial business party.

When the People’s Republic was admitted to the UN General Assembly and took a seat on the Security Council late in 1971, McMahon’s attempt to reconcile opposing pressures finally came to an end. Resiling from engagement with China was no longer an option, and yet China would not accept anything less than diplomatic recognition. The horses had bolted.

Another attempted balancing act came in the middle of 1971 when the South African government sent an all-white Springboks rugby team to Australia. Foreshadowing an October tour by South Africa’s cricket side, the Springboks became a barometer of how fast public opinion could turn on an issue. A Gallup poll taken in March 1971 had found that almost 85 per cent of Australians thought the South Africans should come, and most members of McMahon’s government believed, as Menzies did, that the cancellation of a South African tour of England in 1970 had been a surrender to the “threats of a noisy minority” and were not willing to do likewise.

McMahon genuflected to respectable opinion by making much of his disappointment that South Africa had sent a whites-only team, but he baulked at any real response. “We believe that the [all-white] policy in respect of teams is unfortunate, but it is nevertheless a South African matter, and not our matter,” he said privately during what happened to be the UN International Year for Action to Combat Racism and Race Discrimination.

Having effectively condoned a racially selected team, McMahon’s government then directed that Australia abstain from voting on a UN resolution condemning the application of apartheid in sport. It then helped sustain the tour by making available an RAAF aircraft to ferry the Springboks around the country after the ACTU and its president Bob Hawke promised to impose a “black ban” on the tour. “We are not going to be beaten here,” McMahon said privately.

Disruptive protests met with furious responses from Liberal–Country state governments. Victorian premier Henry Bolte called the demonstrators “louts and larrikins”; Queensland’s Bjelke-Petersen government declared a state of emergency so as to more easily crack heads. Amid the barbed-wire barricades, smoke bombs and police batons, McMahon mused about calling an election with a law-and-order theme.

By the time the South Africans left, the weight of public opinion had shifted completely. McMahon’s own ministers were against an early election and dreaded the prospect of a repetition of the controversy when the South African cricketers arrived in summer. Not willing to admit defeat, the government refused to decide whether that tour should take place. It threw the ball to Sir Donald Bradman, chair of the Australian Board of Control for International Cricket, leaving it to him to make the necessary decision to call off the tour.

Yet another example of McMahon’s balancing act emerged at the end of 1971, when he made clear to a cabinet committee that he supported applications from Indigenous communities in the Northern Territory for leases on consolidated lands, provided they could satisfy criteria related to their association with the land. Had this been translated into government policy, it would have been an acknowledgement that a traditional association with the land should be a basis for land rights claims. His view diverged from those of the cabinet committee members considering the government’s approach to Indigenous issues. The fact that McMahon’s subsequent wavering failed to bring them around was reflected in their decision in late December 1971.

When McMahon issued a statement on Aboriginal policy on 26 January, it featured a gaping hole. The new objectives, though laudable, were overshadowed by the government’s failure on land rights. McMahon announced the creation of a new form of lease but ruled out land claims made on the basis of traditional association. The reason? To do so would introduce a “new, probably confusing component, the implications of which could not clearly be foreseen, and which could lead to uncertainty and possible challenge in relation to land titles elsewhere in Australia which are at present unquestioned and secure.”

The attempt to hew to a conservative course — rejecting a traditional association with the land — and simultaneously announce updated objectives for government policy fell flat. The timing hardly helped: McMahon’s statement came on a day traditionally considered a day of mourning by Indigenous peoples. The statement spurred one of the striking images of that year: four Indigenous men sitting beneath an umbrella as the sun rose on the lawns outside Parliament House the following day, a sign strung up beside them reading “Aboriginal Embassy.”

Failures like these left the government far from the “first, fine, careless rapture” that Menzies had suggested was necessary to stay in office. “There is an imminent feeling of decay about the place,” recorded Liberal MP Bert Kelly when parliament resumed late in February 1972.

Blame for the government’s woes fell almost entirely on McMahon. As Kelly asked his diary, “What the devil do we do next? We’ve got Billy McMahon elected as our leader and obviously he is not doing it at all well and everybody knows this. What we can’t think of is, how do we get rid of him? I suppose the only hope we have is that he suddenly drops dead one day.”

The unrest stirred by dire polling, as well as whispers that John Gorton might try to supplant him, didn’t bring out the best in McMahon. “Christ, he must be mad,” said one MP, after one blundering parliamentary debate by the prime minister. “What is wrong with him?” asked another.

Everything the government and its prime minister did seemed to end in disaster. McMahon’s late-1971 trips to the United States and Britain had been memorable for a mangled toast to his hosts, his wife’s revealing dress and Richard Nixon’s inability to remember his name. A swing through Southeast Asia early in 1972 became an “excursion to blunderland,” declared a Canberra News journalist, extinguishing any hopes of making defence and foreign affairs a centrepiece of a re-election campaign.

But ministers also shared in the blame, with no small number of blunders and public spats occupying headlines. Some ministers dithered; others were disengaged. David Fairbairn regarded the five months he spent as education minister, in 1971, as hard and unrewarding, and departed the portfolio admitting he had not achieved anything.

Environment minister Peter Howson, meanwhile, citing the lack of an explicit directive, did himself no favours when he refused to lend Australia’s support to New Zealand’s criticism of renewed French nuclear testing in the Pacific in 1972, putting the government at odds with public opinion. (A belated move that mainly suggested the government was going along with the public for craven reasons.)

The economic outlook also proved difficult for the government. The Coalition had been nearly broken by a currency revaluation forced upon it when the Smithsonian Agreement — which pegged currencies to the US dollar — came into operation in December 1971. Slowing economic growth and rising inflation spooked treasurer Billy Snedden and McMahon, who were soon at loggerheads over how to get the economy moving in time for the election. The government was caught between the competing objectives of economic rigour and voter-attractive spending.

After a tough budget in 1971, the increased pensions and reduced personal income taxes in the government’s April 1972 mini-budget suggested a new focus on the pending election. As deputy prime minister Doug Anthony admitted, “I wouldn’t be very honest if I said that this [the election] isn’t in the back of our minds.” The budget proper, issued in August, was even more electorally focused: “Taxes down; pensions up; and growth decidedly strengthened,” as Billy Snedden remarked.

The attempt to find a way between change and stasis often saw progress. Under customs minister Don Chipp, the government liberalised censorship policy yet also refused to authorise the publication of Philip Roth’s controversial novel Portnoy’s Complaint in Australia — only for a monied publisher to embarrass the government by evading its jurisdiction and publishing the book anyway. The government was ignominiously forced to remove its ban on Portnoy in 1971, and the following year an attempt to hold the line on the banned Little Red Schoolbook foundered when activists smuggled it into the country and began distributing free copies. Chipp insisted that the government remove its ineffective ban, but Malcolm Fraser and other ministers continued to protest that the book “undermined family and society.”

Other initiatives came too, on an unexpectedly broad front. Writing a decade later, Donald Horne wondered whether McMahon was too busy “plucking policy out of passing straws” to know what he was doing. But in terms of results, Horne conceded, the government modernised the political agenda in a significant number of ways.

Although the government resiled from passing a wholly new Trade Practices Act, it did initiate new laws preventing foreign takeovers. It withdrew the last Australian combat troops from Vietnam, leaving only 128 members of the Australian Army Training Team in the country. It joined the Five Powers Defence Arrangements and the OECD. It passed the Childcare Act, which allowed the Commonwealth to intervene in the childcare sector and helped transform it into a profession supported by research and grants. It increased education spending and the number of scholarship places at universities and TAFEs.

The government also adopted the “polluter pays” principle for environmental protection, and began giving the Commonwealth the capacity to intervene in environmental matters. Howson, for all his grumbles that he had been given responsibility for “trees, boongs and poofters” as minister for the environment, Aborigines, and the arts, was nonetheless the first person to be appointed with explicit responsibility for these policy areas.

Notably, too, the government released its own urban and regional development policy. This was partly in response to Whitlam’s well-established interest in this area, but also a recognition of public demand for Commonwealth action. Meeting that demand required the government to overcome its longstanding aversion to Commonwealth intervention in state responsibilities.

Housing minister Kevin Cairns’s priority was “to seek agreement at all levels that an urban policy is needed” — rather than to actually devise a policy — but McMahon pushed for both the agreement and a policy. He reserved to his authority and his department responsibilities traditionally held by state governments, and then, in September, pushed cabinet to create the National Urban and Regional Development Authority to foster a “better balance of population distribution and regional development in Australia.”

When he introduced the legislation, McMahon stressed the significance of the change that was now manifest: “It marks our recognition that there is a direct contribution that the Commonwealth government can make in national urban and regional development.” It also showed that the government had an answer to Labor’s policies in this area.

“We should be able to tell people where we stand and where we are heading,” McMahon had written in August 1971. Here, perhaps, was the government’s approach in a single phrase: stasis and movement. When McMahon went to Government House to seek a dissolution of parliament, he felt sufficiently confident that his two-pronged approach would be enough to see the government returned. To Paul Hasluck, he predicted the Coalition would pick up two seats in Western Australia and two seats in New South Wales — and perhaps even three in Victoria. He didn’t envision losing any seats except, perhaps, that of Evans, held by Malcolm Mackay.

That prediction was somewhat redeemed: the Coalition picked up two seats in Western Australia and one seat apiece in Victoria and South Australia. But it lost six seats in New South Wales, four in Victoria, and one apiece in Tasmania and Queensland, with the result that Labor took office with a nine-seat majority.

It was a closer result than many would like to think. The rural gerrymander meant that around 2000 votes distributed across five seats could have allowed the government to cling to office. In such an event, the first steps in McMahon’s forecast to Perkin may well have been vindicated.

Why the close result? Some have pointed to the electorate’s innate conservatism, especially after twenty-three years of Coalition rule. Few have suggested that McMahon might have been a factor in limiting the swing — but one of them was his successor as prime minister. Without McMahon’s skill, tenacity, and resourcefulness, Whitlam later wrote, Labor’s victory in 1972 would have been “more convincing than it was.” •

Funding for this article from the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund is gratefully acknowledged.