The men and one woman who have led the Australian Labor Party to victory are a weird mob. For a start, the road to the Lodge is splattered with the type of unpleasantness that we lesser mortals strive to avoid.

As a former NSW premier, the late Neville Wran — once an aspirant to the top job himself — famously said: “You get nothing in the Labor Party without getting up to your armpits in blood and shit. Nothing. They give you nothing.”

Former prime minister Paul Keating agrees with Wran’s assessment, but with one proviso. Most of the rough stuff, according to Keating, occurs in what he dubbed the “mezzanine phase” of a political career: that dangerous liminal space in the Tower of Power between the front door and the lift to the penthouse.

If you want to understand a billionaire, learn how they acquired their first million; if you want to understand a prime minister, find out how they spent their time wading through the befouled foyer of politics.

David Day’s new book, Young Hawke: The Making of an Australian Larrikin, tells the story of Bob Hawke’s life before the Lodge, from his birth in 1929 until 1979, the year he won preselection for the safe Labor seat of Wills and began his final ascent to the prime ministership.

Pedantically speaking, Day’s book covers the first fifty years of Hawke’s life, so it’s not all about Hawke as a youngster. But it is about the creation of a “larrikin,” that much over-used and abused term.

In Australian public life everyone’s a potential tall poppy, unless they’re a larrikin. Larrikins are forgiven their trespasses against taste and decorum; lesser celebrities get cancelled.

Ordinarily, Australian larrikins are beloved sports people like Shane Warne, or renegade intellectuals like Germaine Greer. It’s very rare for a politician to achieve this status. Bob Hawke is possibly the only exception.

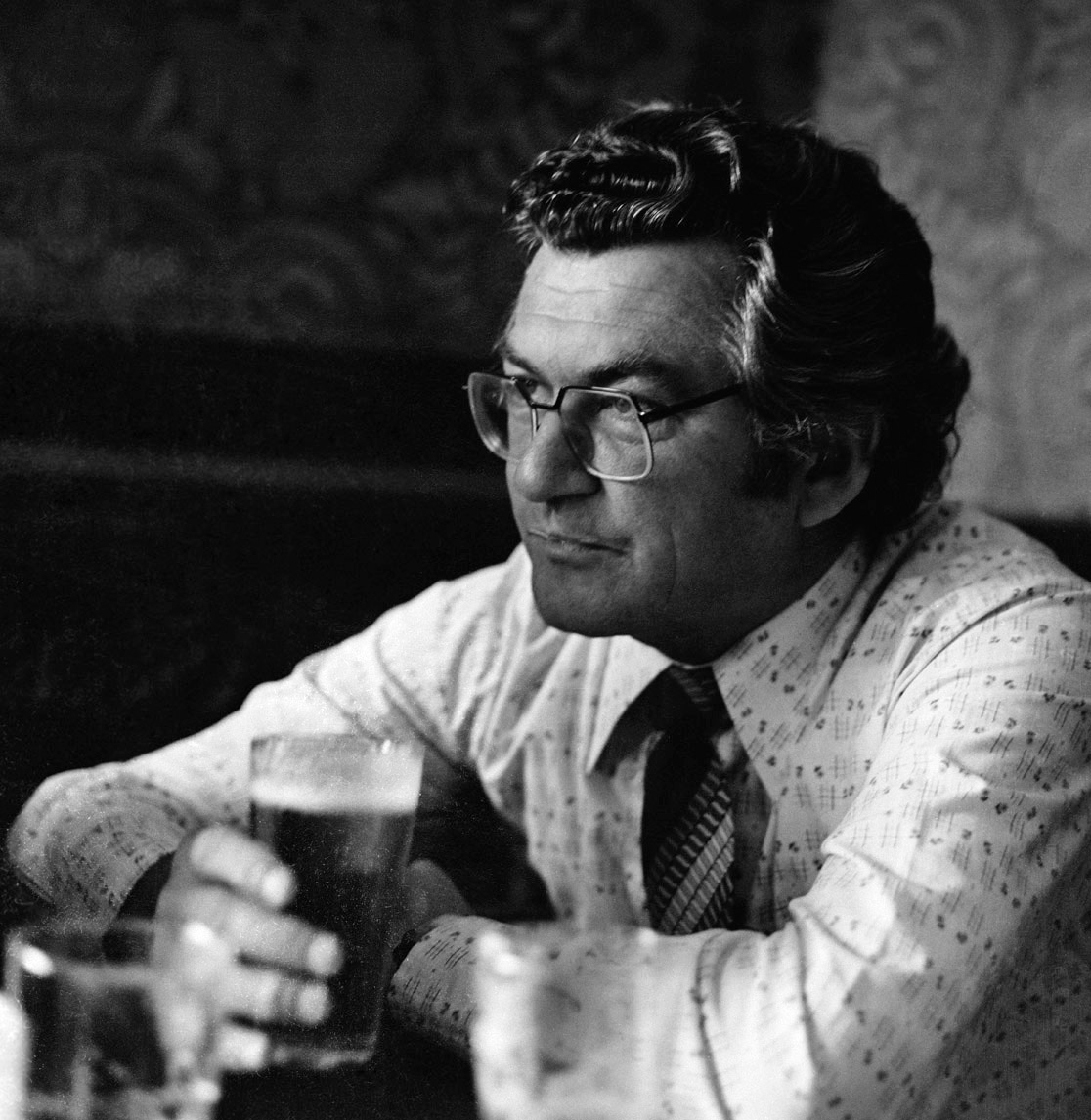

The origin story of Hawke’s larrikinism is, of course, the one about his famous beer drinking record. Contrary to popular belief, however, Hawke did not down a yard-glass in record time at an Oxford pub when he was a Rhodes Scholar. As Day explains, Hawke was made to drink two and a half pints of lager in the dining hall of University College to avoid being punished for not wearing his gown to dinner. He consumed the lager in eleven seconds.

Australian virility — one; English snootiness — zero. Like Warnie, Hawke had vanquished the traditional enemy on its own turf. A legend was born.

And then carefully nurtured. The real significance of the story lies in what Hawke did next. According to Day, Young Hawke made sure news of his record-making scull was published in the Guinness Book of Records. In terms of his later political career, it might have been more important than his Oxford B.Litt. As Hawke himself noted: the “feat was to endear me to some of my fellow Australians more than anything else I ever achieved.”

Like any good historian, Day is adept at debunking myths and making tough judgements. As Day’s clear-eyed examination of Hawke’s life makes plain, his so-called larrikinism camouflaged a multitude of less admirable traits that would have ended the political careers of just about anyone else. Somehow he managed to survive and became one of our best prime ministers. Therein lies the mystery of Robert James Lee Hawke.

The clippings-file contours of Hawke’s life are well known. It looks like an inexorable and heroic rise to the top job. A strong religious upbringing gave him a social conscience. His ambitious mother Ellie imbued him with a sense of destiny. The beer-drinking record set him up as the people’s champion.

Then, via his work at the ACTU, where he advocated for higher wages and settled seemingly intractable industrial disputes, he became the battler’s friend. Finally, as an unstoppable vote-winning machine, he elbowed aside the capable but uncharismatic Bill Hayden and took Labor back into power in 1983, just a few years after the indignities of the Dismissal.

Day chips away at this conventional narrative of Hawke’s life to create a vivid, warts-and-all portrait of the man who became Australia’s twenty-third prime minister.

Long before he became a politician, Hawke was the second child in a family with its own unique dynamic. The most important day in Hawke’s life was probably 27 February 1939 when his older, more talented brother Neil Hawke died of amoebic meningitis.

Neil was the apple of Ellie’s eye and when he died her love for Young Bob became conditional on his fulfilling the destiny she envisaged for Neil. “I had these two problems in childhood,” Hawke would later say. “My mother wanted me to be a girl, and then her son died, and I had, somehow, to replace him.”

The biggest obstacle to Hawke’s success was often himself; the psychology of destiny breeds some hard-to-meet needs and desires. Famous for his self-belief, even he doubted himself sometimes.

The booze nearly destroyed his career. At Oxford he was arrested for drink driving and would have been sent home in disgrace if he hadn’t successfully fought the charges in court. Loutish behaviour during a famous incident at the ANU — including a drunken swim in the ornamental pool at University House — could have seen his reputation shredded for good.

The story of Hawke’s marriage to his first wife Hazel makes for some difficult reading. In her youth Hazel was a bright, talented musician, but Hawke didn’t want her to further her education or work outside the home. What started as a love affair became, at times, a mutual hell. What was behind this unhappiness? Throughout their relationship, Day writes, “Hazel would have to compete with a succession of other women.”

To live in Hawke’s orbit during these years sounds exhausting. I can only imagine what it was like for the man himself. Long hours, stressful work in the glare of the public spotlight, political feuds and enmities, a dysfunctional marriage, extramarital affairs, regular hangovers, periods of depression and ill health, occasionally suicidal thoughts. “Wherever he went,” Day writes, “he couldn’t escape from himself.”

As a young man the future American president Richard Nixon courted his future wife Pat with an assiduity that looks in retrospect just a little bit weird. To win her affection, the young Nixon would chauffer Pat and her other potential suitors along to their dates and then hang around, waiting to drive them home again.

When a character in David Hare’s film Wetherby tells this story, she finishes with the obvious question: “Well, I ask you, what does that tell you about Nixon?” To which her companion replies: “I ask you, what does it tell you about Pat?”

What does Bob Hawke’s long love affair with the Australian people tell us about us?

Hawke was clearly one of Australia’s most successful and effective prime ministers. Blessed with a very talented cabinet, which he ran with aplomb, he won four elections on the trot and made many major — and lasting — reforms, including floating the dollar, creating Medicare and introducing universal superannuation.

Equally, he could be, as women of my mother’s generation would say, “a nasty piece of work,” often towards women, particularly when drunk. What does the story of Hawke’s feted career tell us about Australia’s attitudes towards gender inequality, about the biases of our media, about the myths Australians like to hear about themselves?

Hawke died five years ago. It’s probably time for a more complex view of this complex man to come to the fore. You never get the impression that Day likes his subject very much, but he does have some sympathy for him. At one point he describes Hawke as a “troubled Labor hero.” This is not the usual Hawkian adjective: ambitious; preening; self-centred: yes. But troubled?

After reading Day, “troubled” rings true. The messianic sense of destiny imposed on him from a young age must have been both a blessing and a curse. It gave him the energy and self-belief to achieve his ambitions, but it was clearly a burden; one he often felt compelled to escape from. Courtesy of his mother, destiny with a capital “D” was always hanging over his head. If he failed in the quest set out for him as a small boy, the result may have been existential.

Maybe this is what gave him that skerrick of vulnerability that attracted love. Hawke’s second marriage to his biographer Blanch D’Alpuget was a successful union. Colleagues like his former economics adviser Craig Emerson, who spoke emotionally at his funeral service, remained committed friends to the end.

Day is at work on a sequel volume to be published next year. Perhaps it’ll be called Hawke PM: The Making of an Australian Paradox. •

Young Hawke: The Making of an Australian Larrikin

By David Day | HarperCollins | $49.99 | 432 pages