The temptation is ever present for a historian to try to see parallels between the present and the past. Having spent the best part of two years looking at all twenty-seven former prime ministers – and, more specifically, at how they left office – my perhaps inevitable response to the entanglement of woes that is the Abbott prime ministership is to ask which earlier blighted footsteps are the nearest match.

Certainly, the man the prime minister professes to admire most, John Howard, shared an equally horrible first term – marked by resignations, rorts and policy confusion – that very nearly cost him his job at the first election he faced, in 1998. But the Howard that emerged was a very different animal; lessons had been learned. Will we see a chastised Abbott arise after near defeat in 2016? That, of course, assumes he will survive as leader until then – which was never a question mark over Howard.

Do we look back further into the past and settle on a prime minister who never seemed big enough for the job – and the harder he tried the smaller he looked? There are, to be sure, superficial comparisons between Billy McMahon and Tony Abbott: both hailed from Sydney, both were abnormally ambitious as well as ruthless, both had inflated opinions of themselves shared by few others, and neither was capable of recognising what were, to most observers, obvious limitations.

But perhaps the closest parallel to Abbott lies in the much more distant past, the past of exactly a century ago. And here we come to arguably the least distinguished of all former prime ministers, far and away the most inept and incompetent of them all.

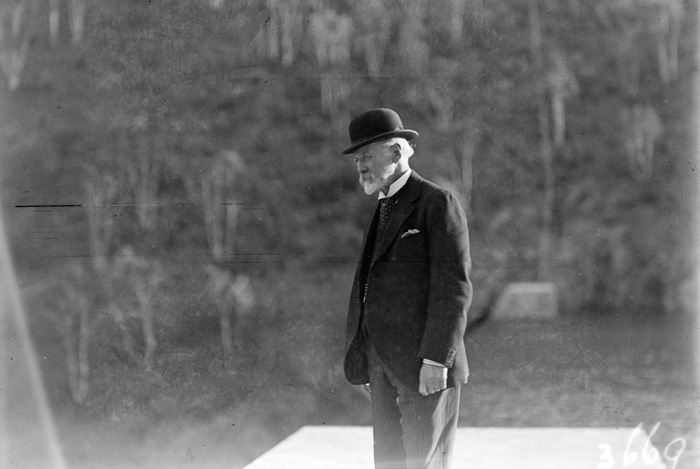

Joseph Cook, a former coal miner and union activist, got his political start with the Labor Party when he was elected to the NSW parliament in 1891. But he soon parted company with the party over the pledge, which bound all members to the majority decision of caucus. Cook, a lay preacher in the Primitive Methodist Church, found his conscience in conflict with that most basic of the party’s parliamentary rules. In an interesting early parallel with Abbott, he had also begun, but had abandoned, studies for the religious vocation.

Just as Abbott had a champion in Howard, so too did Cook in the large person of George Reid, the voluble Free Trade leader in New South Wales. As premier, Reid took Cook into his ministry, and years later, after leading the federal party, he stepped down in his protégé’s favour. Part of the reason Reid resigned was to remove any impediment presented by his leadership to the fusion of his Free Traders with Alfred Deakin’s Liberal Protectionists, designed to create a single conservative party, under Deakin, and take on the burgeoning Labor Party.

The story of how Cook succeeded Deakin on the latter’s retirement in 1913 again offers an eerie parallel with Tony Abbott’s slender victory in the Liberal leadership ballot of 2009. Two serious contenders vied for the job: Cook, who had the support of most of the twenty-one members who favoured retaining the existing tariff, and the redoubtable Western Australian John Forrest, who could count on most of the twenty-four who favoured its increase. Six members, for various reasons, did not attend the party meeting, and when the ballots were cast, Cook and Forrest tied; a Victorian hopeful, the former premier William Irvine, received two votes (his own, and that of his cousin) and a fourth candidate voted for himself. The Irvines switched their votes to Cook. Irvine had reasoned that he could expect high office under Cook but not under Forrest, and he was rewarded with the attorney-generalship. The waters were further muddied by four high tariffists voting for Cook.

Fast forward to 2009. The Liberal party room carried a spill motion against Malcolm Turnbull, and Turnbull lined up against Abbott and Joe Hockey for the ensuing vote. Hockey was eliminated on the first ballot, and then a handful of Liberals who had voted for the spill shifted to Turnbull once they saw that the alternative was Abbott. It is history now that Abbott won by a single vote and that a Turnbull supporter was absent.

Cook won the 1913 election with a majority of one. Just as Abbott would try and fail to persuade two conservative independents to support him in a hung parliament in 2010, Cook failed to persuade the Labor speaker and chair of committees to stay on. What this meant was that in every division in the House of Representatives, Cook had to rely on the casting vote of the speaker. Things were even worse in the Senate, where the opposition held twenty-nine of the thirty-six seats.

Cook’s tenure was always going to be difficult, but his temperament and inflexibility of mind didn’t work to alleviate his difficulties; if anything, they added significantly to a challenge that would test the best of men. He had a number of options from the outset: to try to govern by negotiation – and Labor had shown its willingness by passing Supply – or to close up shop and seek to force a double dissolution. A third option was to seek another House of Representatives election in which to gain a renewed mandate, which he could use as a powerful weapon against Senate obstruction, thereby saving a year of parliamentary inaction and manufactured confrontation. But Cook lacked the imagination to do this, and there is no record of his ever having considered it.

His biographer, John Murdoch, notes that whatever qualities Cook did possess, leadership was not among them. “He could never inspire devotion in his followers, nor the feeling in the country that he was the essential man… He was not fitted for constructive or essential leadership.”

In another similarity with Abbott, Cook was fond of sheeting home to Labor the blame for all ills, even though Labor had so far enjoyed but a single term of office in its own right (1910–13) and its legislative program had owed more to the Barton–Deakin program of the first two parliaments than to Labor ideology. Again, like Abbott’s obsession with the carbon and mining taxes, Cook’s priority lay more in dismantling all vestiges of Labor policy than in initiating those of his own.

Cook devoted his tenure to manufacturing a constitutional justification for a double dissolution – Australia’s first – and even that was based on a contrivance: the two bills designed to be rejected had little real policy significance, relating to a restoration of postal voting and removing preference for unionists in public employment.

Cook persuaded the governor-general to grant him the dissolution but lost the ensuing election in 1914 comprehensively, in what was probably the worst call yet by a prime minister. For almost four decades, until Robert Menzies in 1951, no prime minister entertained the idea of a double dissolution.

Is there, perhaps, a lesson to be learnt here, or might history somehow repeat itself? •