Whether or not Australians of migrant background can bring their parents to Australia for an extended stay is never going to attract as much voter attention as health, education, taxes or jobs. Yet for the second federal election campaign in a row, a skirmish over parent visas has briefly made headlines.

The burst of interest is revealing. It highlights the growing electoral influence of migrant voters but also shows how issues that greatly concern them can often go largely unnoticed in the mainstream media (with SBS Radio a notable exception). It also highlights the complexities and inconsistencies of Australian migration policy. The government is creating a new visa that will enable tens of thousands more migrants to come to Australia for stays of up to ten years at the same time as it is cutting permanent migration to appease voter concern about urban congestion. Perhaps most importantly, the debate over parent visas highlights the perils of policy on the run.

The promise of a new visa emerged from the 2016 election campaign, following a very effective campaign by frustrated migrant communities. The source of their frustration was the difficulty migrant families experienced in trying to bring parents to join them in Australia. The permanent visa categories for parent migration were either prohibitively expensive or involved a decades-long wait. The only alternative was to bring parents out on a twelve-month visitor visa, after which they would have to leave again for at least six months before applying to make a return visit.

Exasperated Adelaide resident Arvind Duggal launched an online petition to home affairs minister Peter Dutton that quickly attracted almost 30,000 signatures, and migrant voters lobbied Labor and the Coalition, including in marginal electorates. Partway through the 2016 campaign Labor promised to create a new visa that would allow parents to remain in Australia for three years; a few days later the Coalition gazumped it with a plan for a five-year parent visa.

That five-year visa is now a reality, and the first applications can be lodged on 1 July. But the slow transition from an open and apparently generous campaign promise to concrete bureaucratic arrangements has left the new visa hedged about with conditions and fees. To qualify as a sponsor, a migrant family’s annual taxable income must exceed $83,000. A family can only sponsor one set of parents. A visit of up to three years will cost a pricey $5000, and a five-year stay will set the sponsors back $10,000. The visa can be renewed once for another stay of up to five years, but the parents need to leave Australia before applying. And visa places are capped at 15,000 per year.

Arvind Duggal, the original petition organiser, told SBS that the arrangements are unfair. He pointed out that the fee for parents coming on a year-long visitor visa is just $140, yet the annual cost of the new visa will be more than ten times that amount. “They are trying to make money from the grandparents visiting their kids, which is un-Australian and unethical,” he said.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the costs and conditions attached to the new visa may have rendered the annual cap on numbers unnecessary. Many migrant families would not meet the income threshold for sponsorship or be able to afford the fees. Sponsoring families will also have to stump up the cost of private health insurance and out-of-pocket expenses for their parents, and act as guarantors for any debt to taxpayers that might arise from a medical emergency.

Recognising an electoral opportunity in the dissatisfaction with the new visa, Labor has used the current campaign to promise major changes if it wins office. Not surprisingly, it made the announcement in the marginal Sydney seat of Reid, held by retiring Turnbull loyalist Craig Laundy, where about 76 per cent of residents have at least one overseas-born parent.

Labor pledged to scrap the limit of one set of parents, a restriction it labelled “heartless, callous and cruel” for forcing families to choose between sets of parents. It would also slash the cost of a three-year visa from $5000 to $1250 and the cost of a five-year visa from $10,000 to $2500. The visa would be renewable in Australia, meaning that parents would be able to stay for a total of ten years without leaving the country. Importantly, Labor also promised to abolish the annual cap on numbers.

The Coalition and its boosters in the media have responding by charging that Labor is opening the floodgates to an unsustainable wave of grey migrants. Immigration minister David Coleman said Labor’s policy “showed a complete lack of regard for sensible immigration and population planning.” On Sky News, Tony Abbott’s former chief of staff Peta Credlin described it as “a shameless bid for votes” and an attempt to “mop up” the damage done to Labor’s reputation among migrants when remarks by NSW opposition leader Michael Daley were released during the NSW state election.

Labor can claim it is simply sticking to its guns — it criticised some of the visa’s conditions when the legislation came before parliament, and the bill eventually passed late last year without its support — but its policy does appear hasty and ill-considered. When asked how many applications might be expected, shadow finance minister Shayne Neumann’s response was decidedly imprecise: “We think it will be very popular.”

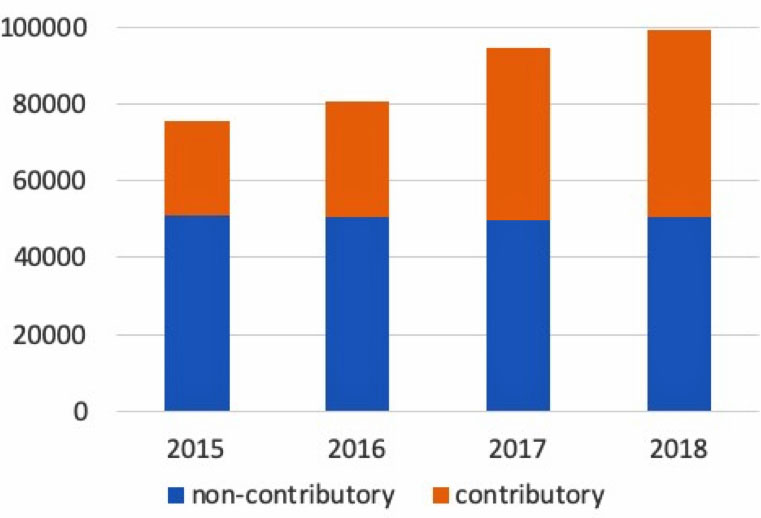

While it’s hard to predict exactly how popular, the most recent Migration Program Report gives a clue. Close to 100,000 applications for permanent parent visa were on hand on 30 June last year, divided roughly equally between the “contributory” and “non-contributory” categories.

A contributory visa costs $47,455, an amount meant to offset some of the costs these migrants might impose on the community as they age. In 2017–18, 6015 contributory places were on offer; while Home Affairs no longer publishes processing times on its website, SBS reports that the average wait is almost four years.

At $6100, a non-contributory visa is comparatively cheap. Last year, though, there were only 1356 places in the program; with waiting times stretching out more than thirty years, few migrants’ parents are likely to live long enough to make it to the front of the queue.

In other words, the pent-up demand for parent migration is huge, and the costs and caps of the permanent parent visa categories are what make the option of a ten-year stay on a temporary sponsored visa so attractive to migrant families. So it seems safe to assume that Labor’s much cheaper, uncapped proposal would see almost all of this backlog shift to the new temporary category.

What’s more, as this chart shows, the backlog for permanent parent visas has been growing by about 6000 applications per year over the past four years, with all the growth in the contributory visa category. Since there will be many migrant families for whom the contributory fee of almost $50,000 is unaffordable, it is again fair to assume that this represents only a portion of the potential annual increase in demand.

Permanent parent visa applications on hand at 30 June 2018

Source: Home Affairs annual reports on the migration program

Another factor will also make the temporary parent visa an attractive option for migrant families. Applicants for the two permanent parent visas must satisfy the balance-of-family test: that is, at least half the parents’ children must be settled in Australia, or they must have more children living here than in any other country. Since the balance-of-family test does not apply to the new temporary visa, parental migration will become a viable option for thousands of migrant families who would otherwise never have been eligible to act as sponsors.

When I wrote about the 2016 election promises on parent visas for Inside Story two and a half years ago, the immigration department was unable to provide basic information that might have helped judge the potential demand for a temporary visa. When I asked, for example, how many people currently use workarounds like the twelve-month subclass 600 visitor visa, I was told that the information was not “readily available.”

In theory, high demand won’t be a problem, because parents on temporary visas will have to be entirely self-financing. They will have no right to any kind of pension, welfare or government-funded aged care, and they will have to pay all their own medical expenses. They will not be allowed to work.

But attempts to draw neat lines between the categories of “temporary” and “permanent” migrants are fraught with problems, especially when those “temporary” migrants have a right to reside in Australia for up to a decade. It’s not hard to foresee difficult scenarios, like these two, developing down the track:

• A son-in-law sponsors his wife’s widowed mother to Australia, but a few years later the marriage ends. The estranged husband withdraws his sponsorship, but the wife can’t step in as a sponsor because she doesn’t meet the income threshold. The mother’s visa will be withdrawn at exactly the point when the distressed wife is in a vulnerable psychological condition, possibly even suicidal, and she and her children need the support of her mother more than ever.

• After living in Australia for more than ten years on a temporary visa, an elderly parent develops Alzheimer’s. He claims he is being subject to elder abuse by his sponsor child. The relationship deteriorates to the point where the child withdraws sponsorship so the parent must leave Australia. But there is no one in the homeland to care for him. Does the father get sent back anyway? If not, who intervenes and who pays for the parent’s high-needs care?

These are not far-fetched possibilities. Human lives are messy and complicated and tend to explode administrative systems and rules, no matter how detailed and thoughtful the design. Cases like these will end up in the media and lead to lengthy, resource-intensive and tortuous appeals to immigration ministers to use their discretionary powers. The more people who use the visa category, the more unforeseen circumstances and unintended consequences are likely to emerge. Such problems may be many years away, and will land in the laps of future governments, but that’s no reason not to take them seriously today.

Parent migration is undoubtedly a difficult issue. All of us can understand a strong desire to keep fathers and mothers close by as they age, to have grandparents pass on cultural and familial knowledge to Australian-born kids, and to express our love for our parents in tangible, practical, intimate ways. There are also much more pragmatic considerations: grandparents can provide unpaid, in-home childcare and other types of household support.

Despite the strong political demand from migrant voters, though, there is no public policy appetite for expanding the number of permanent parent visas. The government has already cut Australia’s migration program by 30,000 places from its peak of 190,000 a few years ago. What is more, both Coalition and Labor governments have for decades skewed the migration program heavily towards young, skilful, healthy applicants with English-language proficiency, on the basis that they are the new arrivals most likely to be economically productive and pay lots of income tax while placing limited demands on the healthcare system and welfare services.

Ageing parents have none of these desirable characteristics. Indeed, in a landmark report on Australia’s migrant intake, the Productivity Commission estimated the “cumulative lifetime fiscal costs” of a migrant parent on a permanent visa in 2015 to be “between around $335,000 and $410,000 per person.”

The temporary parent visa might seem to offer a way out of this dilemma. Migrant families can have their parents join them in Australia at no cost to the public purse and without needing paid work. But it risks creating a new cohort of people who are not quite Australian — who live here for an extended period but have restricted rights, no say in political decision-making, no political representation and no access to public support in times of crisis. •