When Spike Lee does history, what we see is pretty crisp. He likes a clean, clear image, often with bright colours. From the Sesame Street–like exteriors of Do the Right Thing back in 1989 through to the startling, candy-coloured zoot suits in the early scenes of Malcolm X, there is something almost wistful in his imagery. Who knew the past was so clear-cut and straight-out stylish? But then, Lee keeps his film-making afloat with regular gigs making commercials for the kind of sneakers teenagers like. Spike Lee has style. It’s one of his hallmarks.

When Spike Lee does history, he is also resolute. And angry. His furious persistence in reminding Americans of their racist past is a rare, honourable mission in popular American cinema. To quote William Faulkner, a writer who knew a thing or two about movies and about the American South, “The past is not dead. It’s not even past.”

And so to BlacKkKlansman, a film that begins with a clip from Gone with the Wind and news footage of a racist politician denouncing school integration, and concludes with a stunning, powerful montage of the rally in Charlottesville, Virginia a year ago this month, the rally at which a white supremacist rammed his car into a crowd of counter-protesters, killing one woman and injuring others. Along the way, he shows us Ku Klux Klan followers chortling with delight as they watch D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation. This, then, is a Spike Lee film about representation. I’ll come back to that.

First, the story. BlacKkKlansman is adapted from a 2014 autobiography by Ron Stallworth, a black police officer in Colorado Springs who managed to infiltrate the KKK. It began as a producer-driven project, with Lee signing on to direct in 2015. He is one of four people credited with the screenplay, and as the film developed he adapted it as a vehicle for commentary on the present.

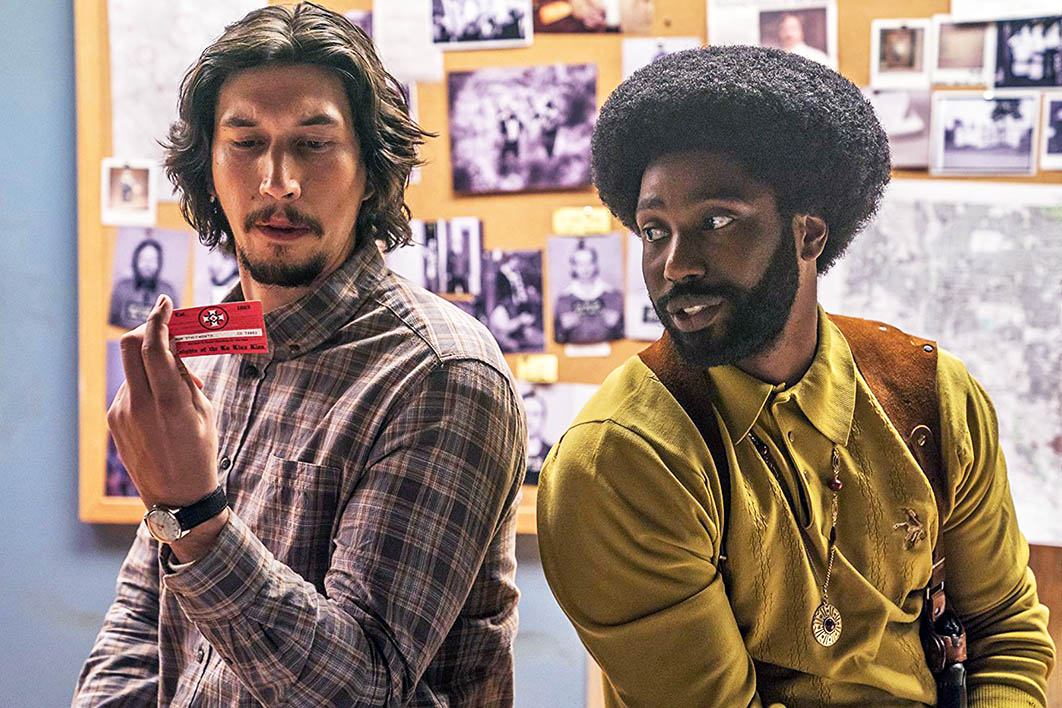

John David Washington plays Stallworth, and a laid-back Adam Driver plays Flip Zimmerman, the white detective enlisted by Stallworth to go to Klan meetings in his place. The film diverges a little from Stallworth’s memoir: there are more heroics than in reality, and the film acknowledges, but then passes rapidly over, the fact that black student organisations were the major target of police intelligence and the FBI in those years, as the Black Power movement spread across campuses.

One of the most moving scenes in the film comes early on, when Stallworth attends a student rally addressed by the former Stokely Carmichael (Corey Hawkins), who by this stage had changed his name to Kwame Ture. It is a speech about beauty, and African-American self-hate, a speech in which Carmichael/Ture calls on the students to reject white definitions of beauty.

“It’s time for you to stop running away from being black,” he says.

“You must define beauty for black people. That’s Black Power.

“Beautiful is usually defined as someone with a narrow nose, thin lips. Pink skin.

As he speaks, Lee’s camera pans and pauses to study rapt faces. Black, beautiful faces.

“Hell no. Our lips are thick, our nose is broad, our hair is nappy. We are black, and we are beautiful.”

This is Spike Lee the stylist at his very best. The rhythm itself, of image, sound, speaker, audience, is beautiful. The rhythm itself is power.

Another searing moment comes when Jerome Turner (Harry Belafonte, fine-featured and dignified at ninety-one) sits quietly in a chair recounting to a roomful of students the atrocious lynching of a young black man, Jesse Washington. It happened in Waco, Texas in 1916, and is one of the best-documented of some 3446 lynching of black Americans between 1882 and 1968. (The Tuskegee Institute, founded by Booker T. Washington, recorded 1297 lynchings of whites in this same period.) Children were let out of school to see the boy’s burnt, mutilated corpse dragged through the town. A local photographer took pictures and sold them as postcards. This is Spike Lee the historian at his best.

Within this scene, Lee intercuts clip after clip of that footage of Klan members in the 1970s giggling at black “piccaninnies” in scenes from The Birth of a Nation. The story Turner tells is so horrific — the script is said to draw on eyewitness accounts (collected by a white feminist journalist) published by W.E.B. Du Bois — I was, at first, infuriated by the cross-cutting. I wanted the Belafonte sequence to be given its own space.

I was also troubled by how Lee represents those Colorado Springs Klansmen. Some are vicious and paranoid, one or two are shrewd, but a couple are very stupid: the giggling fat fools beloved of popular cinema tropes. They are united by hatred and a weird idolising of KKK leader David Duke, who sought then, and since, to bring the KKK into the political mainstream.

This scene has a backstory. When Lee was at film school, he was infuriated by the way The Birth of a Nation — which did, for a while, boost declining Klan membership — was used to demonstrate D.W. Griffith’s innovations in editing without acknowledging its social context. There’s no doubt Griffith pioneered huge leaps in the storytelling of cinema. Eisenstein is among those who learned from him, and acknowledged it.

Is Lee justified in using the technique against the white supremacists, then and now? It’s a profoundly disturbing sequence, and a masterly act of cinematic revenge.

BlacKkKlansman is rich in cinematic references. There are tributes to the stars of the so-called “blaxploitation” films of the seventies, films such as Shaft and Foxy Brown that put black characters onscreen as heroes for the first time. And the way he does it — in a lighthearted wrangle between Washington’s Stallworth and black student leader Patrice Dumas (Laura Harrier) — tells us something: these films matter.

They didn’t have the same widespread releases in Australia but I can tell you, watching Gordon Parks’s Shaft in a cinema full of cheering Papuans in Port Moresby in 1976 brought home to me how important it is for all of us to see ourselves onscreen. Movies matter. What we see onscreen shapes the way we understand the world, and our own place in it.

In a sense, then, beneath what could have been just a quirky comedy about an odd historical moment is a film about representation. How can a black American cop possibly represent himself as a white supremacist? Answer: with help. Stallworth runs the sting, and the phone contacts: Flip Zimmerman is the cop who impersonates the “real” Ron Stallworth when he meets with Klan members. Confronted with real hatred of Jews, he begins to ask himself questions about his own identity. It’s just one of many moments of reflection in a film that propels itself forward compellingly, a testament to Lee’s mastery of rapidly shifting moods.

“Identity politics” has some very dangerous cul-de-sacs, and we’re seeing some of them acted out right now, in Washington and Canberra, in Warsaw and Myanmar. Lee’s film affirms something very important. We need good cops. We need each other.

We need music too. The closing track, a hitherto unreleased recording by Prince of “Oh, Mary Don’t You Weep,” provides the perfect space for contemplation as the credits roll.

Back in March, some were puzzled when I lauded Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Phantom Thread as the Oscar-nominated film most likely to endure. American Academy voters didn’t get it. Now film critics around the world — some 437 of them — have awarded it the Grand Prix of FIPRESCI, the International Federation of Film Critics. If you’ll permit me this brief comment: ha! •