For those seeking a credible challenge to India’s Hindu-supremacist government of Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party, a meeting of opposition parties in Bengaluru on 18 July sparked a frisson of hope. For sceptical observers, however, “1977” and “1989” flashed on the big video screen of memory to subdue expectations.

In Bengaluru, the leaders of twenty-six opposition parties reached a joint agreement to fight next year’s national elections as allies. They even produced a name, an acronym and a slogan.

The name is tortuous — the India National Developmental Inclusive Alliance — but the creators love their acronym: INDIA. And lest anyone think their opponents will ridicule them for displaying such a “colonial mentality” by using the English word “India,” they chose a slogan of Jeetega Bharat — “Bharat will win.” Bharat is the term for the South Asian land mass used in Hindu religious texts and much preferred by the BJP and its spin-offs.

Getting twenty-six different sets of politicians into one place and ready to adopt a united statement required a lot of diplomacy. Desperation helped: there is a feeling that if Modi and the BJP win a third five-year term, BJP dominance, and doctrines of Hindu supremacy (Hindutva) will become irreversibly embedded in the apparatus of the state.

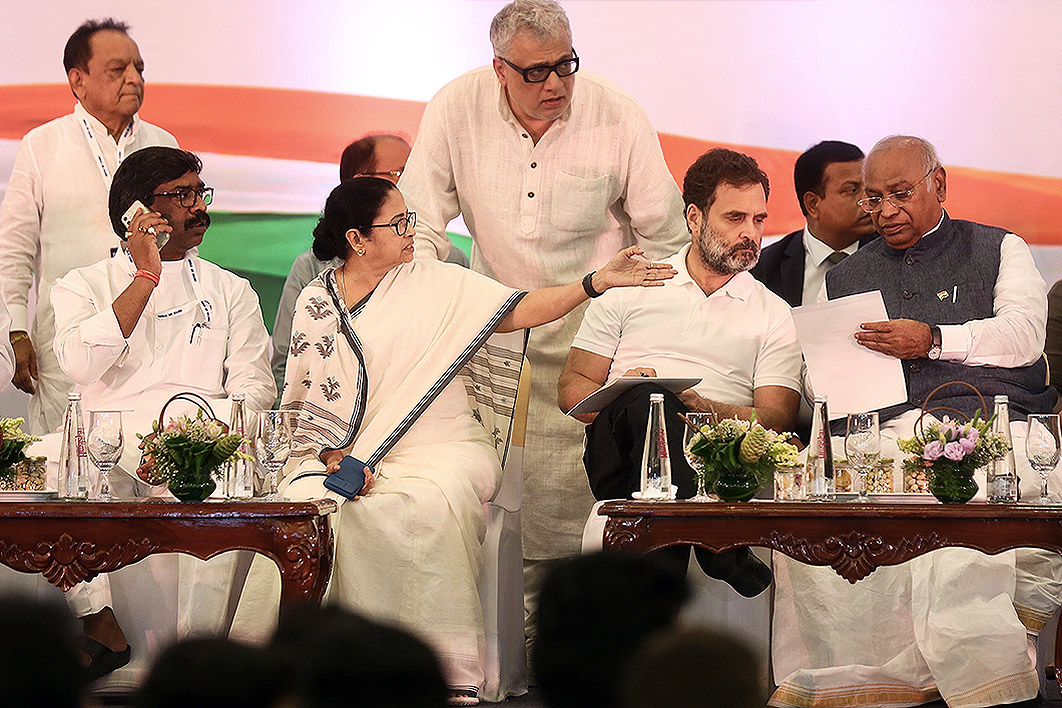

One man near the heart of the conclave was the Congress party’s eighty-one-year-old president, Mallikarjun Kharge. Kharge is a Dalit (formerly “untouchable”) from the southern state of Karnataka. Though he is a long-time devotee of Sonia Gandhi and her family, he is also an experienced warrior, “efficient at soothing ruffled feathers… Nobody can call him a lightweight,” according to an informed journalist.

The multi-party meeting was held in Bengaluru because the Congress party, with Kharge as a key organiser, defeated the BJP state government in Karnataka’s elections in May. Here was a success story that suggested the BJP, which controls only half of India’s twenty-eight state governments, could be beaten.

At the 2019 parliamentary elections, the BJP and its allies won 332 seats out of 543 with 47 per cent of the vote. The twenty-six parties gathered in Bengaluru won 144 seats and 39 per cent of the vote. By competing against each other as well as the BJP, in other words, the INDIA parties split the opposition vote.

This time, the leaders say, only one candidate will run under the INDIA banner in each seat. But this sort of agreement will be hard to achieve in many seats, since a number of the parties are fierce rivals in their states.

The INDIA initiative provoked a more nervous response from the BJP than might have been expected. It summoned a meeting of its own National Democratic Alliance to coincide with the INDIA meeting. This seemed surprisingly defensive, because the thirty-eight allied parties assembled in Delhi offer the BJP little more than a dozen additional seats.

The BJP president took the opportunity to remind audiences that participants in the INDIA alignment revealed “only one unity — that of taking care of their family interests.” He reeled off names of eight INDIA parties led by offspring of long-established politicians. Narendra Modi, on the other hand, has long portrayed himself as single, selfless and dedicated only to the nation.

What is the relevance of 1977 and 1989? In both years, opposition groups were desperate to prevent continued election victories of the Congress party of Indira Gandhi (1977) and Rajiv Gandhi (1989). They made alliances and even formed governments. Yet the 1977 effort crumbled in two years, and by 1980 Indira Gandhi was back as prime minister. The minority government that emerged from the 1989 coalition collapsed within a year, and by 1991 Congress was back in government.

Today, a handful of commentators see cracks in the BJP machine. They point to the problems of managing an organisation claiming 180 million members. As the party extends its grip to every Indian state, they reckon, it is getting caught up in the horse-trading, corruption and disillusion that eroded Congress.

Top-down direction will undermine belief in a party whose members once provided input and could rise from the ranks. Long-time true believers will be alienated by the arrival of drifters and grifters climbing on a bandwagon they hope is also a gravy train. It happened to the Congress party: once the idealism of the national movement was gone, little remained except a weak appeal to a disappointing “socialism.”

Today, there are two big differences. First, India has 900 million broadband subscribers and every party member of the BJP and its affiliates has a smartphone. A party structure based on participation and discipline can be maintained on a daily basis. At the level of the polling booth, BJP “booth captains” are capable of reporting, transmitting and acting. Party members can be held close.

Second, the Hindu-supremacist project of the BJP has a powerfully simple ideology that can constantly renew itself. There will always be another mosque built where a temple should be, an inter-faith marriage that cries out to be rectified, or a Christian plot to convert innocent tribal people to a foreign faith. If the economy goes bad, the reason probably lies with such “foreign” tumours.

The INDIA allies are scheduled to meet in Mumbai in August, ideally with key state leaders like Nitish Kumar, chief minister of Bihar (forty seats in the Lok Sabha, parliament’s lower house), and Mamata Banerjee, chief minister of West Bengal (forty-two seats), playing leading roles. But the Gandhi family will continue to be central, and Mallikarjun Kharge will need all his feather-smoothing skills if a credible electoral alliance is to take flight. •