Among the insights provided by the Palace Letters, released yesterday by the National Archives, is Sir John Kerr’s description of himself as “an extrovert and activist.” The comment comes in a letter on 24 November 1975 — thirteen days after his dismissal of the Whitlam government — to “My dear Private Secretary,” Sir Martin Charteris, the Queen’s right-hand man.

It’s clear from the letter that the governor-general is hurt by the attacks on him but is taking the advice of “my few close friends and advisers” not to defend his position publicly, although “this is difficult for an extrovert and activist.” He suggests he could still be tempted, though, if “the calumnies and criticisms become unbearable.” The message that comes back from Charteris is unambiguous — please don’t — and that advice is accepted.

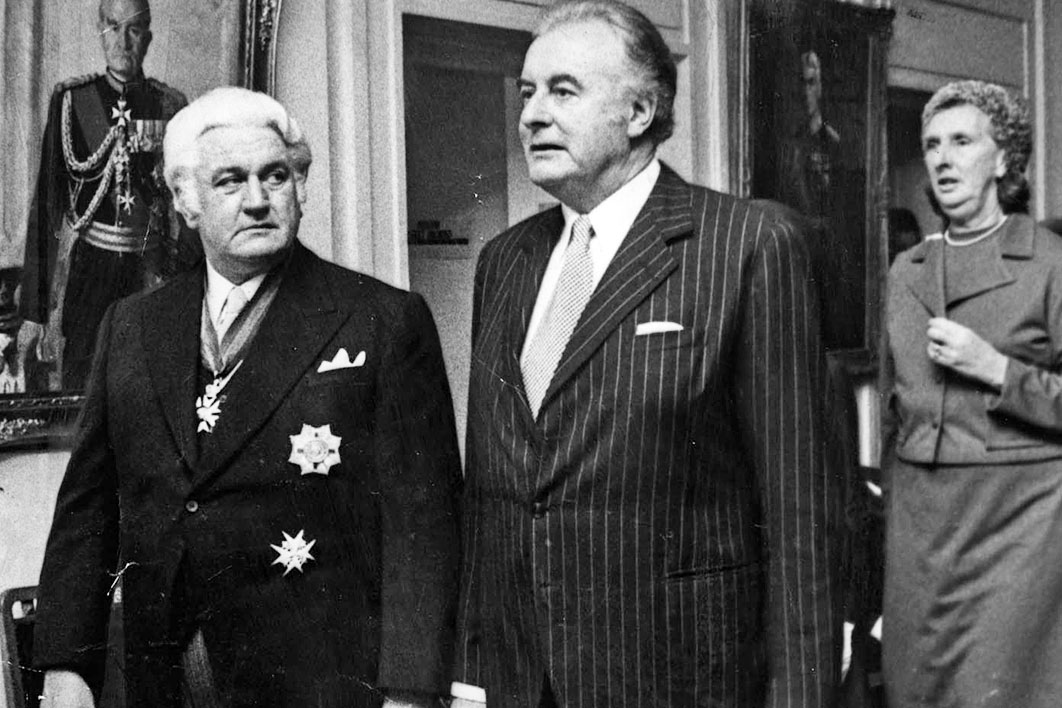

With due allowance for hindsight, Gough Whitlam made a bad choice in appointing Kerr to a position where he revelled in the trappings of office and refused to see himself as a “cipher” — the description once used by Whitlam — who was duty-bound to follow the advice of the democratically elected prime minister. It points to one of Whitlam’s weaknesses: he was a poor judge of character.

The letters confirm what Kerr has previously claimed: he did not tell the Queen beforehand of his action on 11 November. In his letter to Charteris on the day of the dismissal, he writes: “I should say that I decided to take the step I took without informing the Palace in advance because under the Constitution the responsibility is mine and I was of the opinion that it was better for Her Majesty not to know in advance, though it is, of course, my duty to tell her immediately.”

This is an impeccable exposition of the principle that the Queen should be kept away from political controversy. But the letters reveal much more: the months of voluminous correspondence between Kerr and the Palace that not just kept the Queen informed of the unfolding political and constitutional crisis but also canvassed all the options available to him, including dismissal. Most strikingly, the response from Charteris, who was passing much of the correspondence on to the Queen, was to support Kerr in his view that he could use his reserve powers and to commend him once he had done so.

On 4 November, a week before the dismissal, Charteris writes to Kerr in the following terms:

When the reserve powers, or the prerogative, of the Crown, to dissolve Parliament (or to refuse to give a dissolution) have not been used for many years, it is often argued that such powers no longer exist. I do not believe this to be true. I think those powers do exist, and the fact that they do, even if they are not used, affects the situation and the way people think and act. This is the value of them. But to use them is a heavy responsibility and it is only at the very end when there is demonstrably no other course that they should be used.

Here Charteris was taking a partisan position, even if the legal position was accurate. It was Whitlam who argued that the reserve powers did not exist or, if they did, that they were a dead letter. It is the difference between law and convention. The governor-general is the constitutional head of the armed forces, but no one suggests he or she should be the one calling out the troops. Whitlam’s argument was that in a democracy the power to dissolve parliament and call an election could be exercised only on the advice of the prime minister. Others disagree, but that is not the point: Charteris was siding with Kerr and the Liberals against Whitlam.

More than that, he was actively supporting Kerr: “I think you are playing the ‘Vice-Regal’ hand with skill and wisdom.” While Charteris counselled that the reserve powers should be used only as a last resort, he never suggested they should be avoided altogether.

After the speaker of the House of Representatives, Labor’s Gordon Scholes, writes to the Queen on 11 November asking her to restore Whitlam to office as prime minister on the grounds that he continued to command a majority in the lower house, Charteris replies that only the governor-general could do this. “The Queen has no part in the decisions which the Governor-General must take in accordance with the Constitution.” (My emphasis.)

This too was siding with the Liberals, who argued that the governor-general had no alternative but to act, and against Labor, which argued he must not.

Charteris not only supports Kerr: he is effusive in his praise of him. When Kerr tells him after the dismissal that he received a complimentary letter from Sir Robert Menzies, Charteris says he is “delighted… It must have been reassuring to find that he thinks history will credit you with having acted rightly.”

History has not been so kind. Though it is generally accepted that the reserve power of dismissal does exist, there remains fierce argument over whether it should have been used.

Kerr was faced with a deadlock created by two implacable political enemies unwilling to give ground. But there is substantial evidence that the situation could have been resolved politically. By 11 November a number of Liberal backbenchers were prepared to concede defeat and pass the budget. Kerr made a series of political judgements: that the opposition senators would not break ranks; that Whitlam’s proposal to temporarily fund government services through the banks would not work; and that an election had to be held before the end of the year.

At the same time that Kerr was canvassing his options and ultimate intentions with Charteris, he was keeping Whitlam in the dark. More than that, he was actively deceiving him by suggesting he was playing a passive role, and giving no hint of his intentions for fear that Whitlam would ask the Queen to sack him first. At the same time he was leaving Malcolm Fraser confident enough to stick to his guns in blocking the budget at a time when he was coming under enormous pressure, including from members of his own party, to buckle.

Kerr’s justification for deceiving Whitlam was to avoid exposing the Queen to an impossible situation. As far back as September, before the opposition had blocked the budget in the Senate, Kerr is expressing concerns that Whitlam would ask the Queen to sack him before he had a chance to sack Whitlam. Charteris is sympathetic but ultimately offers Kerr no comfort, writing on 2 October:

If such an approach was made you may be sure that The Queen would take most unkindly to it. There would be considerable comings and goings, but I think it is right that I should make the point that at the end of the road The Queen, as a Constitutional Sovereign, would have no option but to follow the advice of her Prime Minister.

Nine days after the dismissal, Kerr raises with Charteris whether he should have given Whitlam prior warning of his intentions to give him the option of calling an election rather than be sacked:

History will doubtless provide an answer to this question but I was in a position where, in my opinion, I simply could not risk the outcome for the sake of the Monarchy. If in the period of say twenty-four hours, during which he was considering his position, he advised The Queen in the strongest of terms that I should be immediately dismissed, the position would then have been that either I would in fact be trying to dismiss him whilst he was trying to dismiss me, an impossible position for The Queen, or someone totally inexperienced in the developments of the crisis up to that point, be it a new Governor-General or an Administrator…

Maybe, but this didn’t justify the ambush of Whitlam. It was one thing for Whitlam to threaten to go to the Queen as a means of putting pressure on Kerr; it is uncertain whether he would have acted on that threat. Kerr was more focused on protecting the monarchy than on safeguarding Australian democracy.

The correspondence captures the bizarre nature of our system of constitutional monarchy: the Queen, sitting on the other side of the world, has a role in our system of government that, though largely symbolic, can on rare occasions involve real decisions. Kerr’s fear of dismissal points to a flaw in the system that has yet to be addressed, along with the Senate’s power to block supply — the trigger for the 1975 constitutional crisis. The Queen has less independent power in Britain than she does in Australia.

The National Archives released the Palace letters on Bastille Day, a celebration of the French revolution. The Palace letters deserve to revive the debate on an Australian republic. •