Rememberings

By Sinéad O’Connor | Penguin | $45 | 304 pages

Rememberings is a wonderful title for a memoir, especially Sinéad O’Connor’s. Not only does it capture the selective nature of what is remembered, it also sounds lovely with an Irish lilt. “Rememberings” are personal and precious; they don’t abide by the rules of conventional memoir. The word conjures an offering — which her memoir certainly is — as well as the shards of memory left over from (in Sinéad’s case) the accumulated effects of childhood trauma, long-term marijuana use and a hysterectomy-induced breakdown. “Rememberings” can be prompted by music and even take the form of songs. In her prologue, Sinéad writes that she hopes the book makes sense, but “if not try singing it, and see if that helps.”

I am breaking reviewer protocol here by referring to the author by her first name because I have been a huge fan since I first saw her on television singing “Mandinka” back in the late 1980s, when I was still a girl and she was barely an adult. To millions around the world, fans or not, Sinéad O’Connor is Sinéad. As she recounts, Americans have mangled the pronunciation of her name, but she’s still Sinéad. She bears no ill will towards them (and as a teenager, she worshipped Americans), except maybe for Prince, who wrote her biggest hit single, “Nothing Compares 2 U,” and doesn’t come off well in the chapter dedicated to him. Their encounter is frightening and slapstick, and while Prince is no longer around to defend himself, I believe Sinéad. In sweet revenge, she nicknames him “Fluffy Cuffs.”

As the Prince vignette hints, Sinéad is a riveting narrator: warm, funny and candid, with a refreshing libidinous streak. Now in her mid-fifties, she focuses in Rememberings mainly on her troubled childhood, rise to fame and celebrity years, with more memoirs enticingly promised. In this case, her stated desire is to “let the child inside me speak because she needed to speak.” And as she does, we are reminded how very young and vulnerable she was when she became stratospherically famous, but also how defiant and self-possessed, especially when it came to her music.

Rememberings begins by offsetting affectionate tributes to her parents, siblings and extended family with harrowing accounts of her mother’s abuse and neglect, and a profound sense of loneliness. As a girl, Sinéad felt so starved of parental love that she knocked on neighbours’ doors in her Dublin neighbourhood asking if she could be their child. For a time, Elvis Presley is her father substitute — along with God — until he dies, making way for Bob Dylan.

Sinéad’s descriptions of the music and musicians who have moved her are exquisite. Dylan’s “voice is like a blanket” and she sees from the album cover “he’s as beautiful as if God drew breath from Lebanon and it became a man.” This intense love of music she shares with her mother, whose record collection was spread across their big dining table “like a deck of cards.”

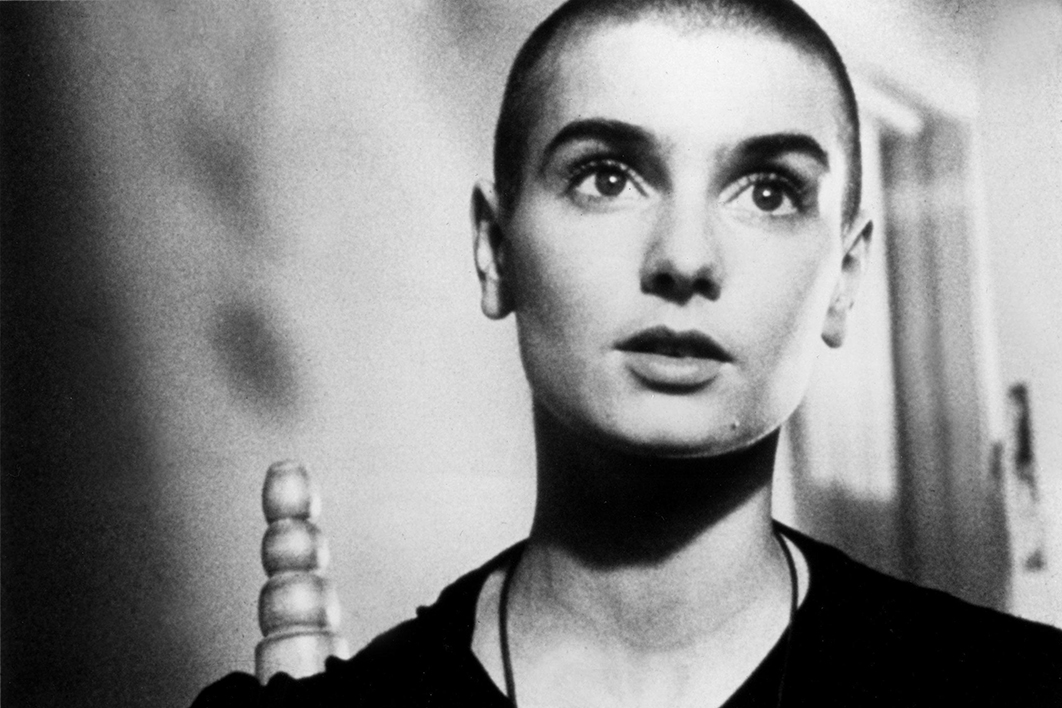

Although her mother dies just as she’s embarking on her music career, she hovers over it from the beginning. “Songs are ghosts,” Sinéad writes, and “Troy,” from her debut album The Lion and the Cobra (1987), is one of many she has written and sung for her mother. When she records the demo, she makes Chris from her record company sit outside. He comes back in “really shaken” and makes her “play it over and over.” It’s a delight to read of Sinéad’s pride in her music, in how the music affects people, and in the decisions she made along the way. These include shaving her head and getting pregnant with her first child Jake before her first album was even released. (Sinéad would go on to have three more children, each to a different father, and she devotes a loving chapter to them in which she confesses what the reader has probably already surmised: “it’s difficult to be a good mother when you’re a touring musician.”)

Sinéad’s second album, the now-classic I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got (1990), almost wasn’t released, with Nigel Grainge from Ensign, her record company, declaring it “too personal; it’s like reading someone’s diaries.” Later, the Edge from U2 tells her he could only listen to her 1994 album Universal Mother once, because “it was too personal.” Again, this makes her proud: “too personal” is her key register, though not the only one, as she details in an annotated discography in the last third of the memoir.

The backlash against Sinéad began when she refused to attend the 1991 Grammy Awards, but peaked when she tore up a photograph of Pope John Paul II on Saturday Night Live in 1992 in protest against child sexual abuse — at the height of her fame, and well in advance of wider revelations of systemic abuse in the Catholic Church. I’d forgotten a third controversy: the brouhaha that erupted when she chose not to have “Star-Spangled Banner” played before a show in New Jersey. Her critics ranged from MC Hammer, who sent her a first-class ticket back to Ireland, to Frank Sinatra. During this fevered period, Sinéad still managed to have lots of fun — sexy times on the road, going undercover at a protest against her — but some of the most telling chapters speak volumes because of what is left out or only briefly mentioned.

There’s a sense of both catharsis and reclamation in how Sinéad relays these events. In the conventional telling, she capsized her career; in hers, she liberated it and herself. As she writes, “I never signed anything that said I would be a good girl.” At heart and in spirit, she’s a punk and a rebel. At the peak of her fame, her kindred spirits were the Rastafarians she was hanging out with in New York’s Lower East Side and hip-hop artists like Public Enemy, whose symbol she shaved onto the side of her head for the 1989 Grammys in protest at the censorship of rap music. Her declared affinities, as an Irish woman, with Black and colonised peoples might raise more eyebrows these days, but this is her truth and she honours it.

As a narrative, Rememberings dissipates at the point Sinéad became what she calls a “pariah.” Midway through writing the book, she had a radical hysterectomy “followed by a total breakdown,” and by the time she recovered from it she was no longer able to remember much of what came before it. She has no regrets, but there have clearly been costs. Rememberings, like many of her songs, moves from whispers to screams to ecstasy and back again. And like Sinéad’s music, it eschews the notion that art can be “too personal.” She would know. •