“If you want to know about America, study Detroit,” they say. That’s true enough. The glowing CBD, the pleasant suburbs, the fine old institutions and the new industries fired by new technology — America the good. The crime, corruption, poverty and addiction, the race and class divide, the derelict suburbs — America the bad. A fallen city. Yet the furious belief that the city will revive, will be born again, that God will be in the whirlwind — America the eternally hopeful.

In the first half of the twentieth century, white folk from the economically depressed regions of the United States, especially Appalachia and the South; Black folk from the South and east-coast cities where wages were low and jobs hard for Blacks to get; Poles, Greeks, Irish, Italians, Germans, and people from the Middle East and the countries of Central America — all were drawn to Detroit by the unstoppable car industry and the promise of five dollars a day. Now a little over half a million people live in a city which in 1960 was home to 1.8 million, the fourth-biggest city in the United States. And 82 per cent of the population is now Black.

Detroit gave America millions of T-Model and A-Model Fords. It gave the world the methods of mass industrial production known as Fordism by which the cars were made. Fordism owed something to the scientific management theories of Frederick Winslow Taylor, something to the disassembling of cattle on the meat-processing chains of Chicago slaughterhouses, and something to the ruthless genius of Henry Ford. The assembly line did more than produce goods efficiently: it changed common human experience, the relationship between human beings and machines; between the mind and the body, Jean-Paul Sartre said, and Charlie Chaplin demonstrated it on film.

Fordism was more than the assembly line. Inspectors from Ford’s “Sociological Department” routinely visited employees’ home to make sure they were meeting company standards of cleanliness and sobriety and living the “American lifestyle,” which was to say the essentially petit-bourgeois ideal of “normal” nuclear families and regular churchgoing. Henry Ford believed in a melting pot of cultures from which standardised Americans would emerge like his standardised cars.

In pursuit of this ideal in the thirties he offered something like a corporate alternative to Roosevelt’s New Deal — which he hated. He provided low-cost food, low-interest loans for houses and home improvements, and he built schools. The Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci wrote that the dependence created by these measures fostered in turn the discipline and compliance workers needed to withstand the pressures of sped-up production lines. The process by which the capitalist ruling class gained the “consent” of labour, and society more broadly, he called hegemony. Forty years later the “invisible power” that ruled minds and bodies became a central concept among New Left theorists, and in fragments, a trope of spaced-out hippies.

“Historical fact: people stopped being human in 1913,” Jeffrey Eugenides said in his novel set in Detroit, Middlesex. Fordism was taken up in all the advanced capitalist countries, and by Joseph Stalin. Stalin admired the “indomitable efficiency” of the American industrial system. He had no Marxist or any other kind of misgivings about subjecting workers to stupefying repetition, reducing them to cogs in a machine or alienating them from the product of their labour — albeit, in the US at least, with the prospect of buying it on hire purchase.

Ford built a plant for Stalin in Gorki (Nizhny Novgorod). Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany also studied and adopted Fordism, and Hitler took further inspiration from Henry Ford’s antisemitic propaganda. Detroit was also home to the country’s other leading antisemite, the Catholic priest Charles Edward Coughlin, “Father Coughlin,” whose anti-capitalist, anti-communist, anti-Black, pro-fascist radio programs reached upwards of thirty million Americans, a quarter of the population. Naturally, the fascist governments of Italy and Japan, which, like the Nazis, sent emissaries to Detroit to learn from Ford’s methods, were not put off by the company’s violent repression of unionists, the system of spies and thugs it employed, and its nasty puritan snooping on the private lives of employees.

Ford’s assembly line was famously memorialised by Diego Rivera’s colossal murals in the Detroit Institute of Arts. That Henry Ford’s only child, Edsel, should have commissioned a Mexican communist is surprising enough. The strange twist is that he did it in 1932, the year Ford’s 3000-strong machine-gun toting security department shot dead five striking workers and injured a couple of hundred others at the River Rouge plant.

But nothing that happens in the United States is ever truly surprising. In the incessant swell of cliché-riddled patriotism and dutiful observance of social rituals, its peasant-like provincialism and maudlin religiosity, it is easy to forget that America’s sharpest critics have generally been American, and that the visionary, the iconoclast and the rebel are prized constituents of the culture.

And sons turn against fathers sometimes. Edsel Ford was a bit of an aesthete. He changed the shape of his father’s cars. And he liked art. In the 1930s, he was president of both the Ford Motor Company and the Detroit Arts Commission. He commissioned Rivera and took him to Ford’s famous Albert Kahn–designed Rouge plant — a complete production system operating in ninety-three buildings on 2000 acres. The artist saw the forges and steel mills, the coke ovens, the glass factories, and the railways and the ships that crossed the lake with the raw materials to feed them; the foundries where, in smoke and steam, men — mainly Black men — converted the iron into engine blocks and cylinder heads, and thousands of other men on the assembly line performed their allotted tasks in the few seconds apportioned them: tasks so simple, Henry Ford declared, a worker needed to be “no smarter than an ox.”

The cars rolled off the line and out into the world, where Americans drove them into the sunlit American future. At least the advertising agencies portrayed it that way. This was modernity. This was the United States.

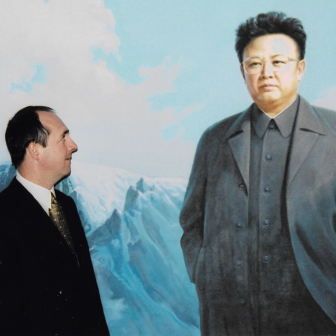

On four walls of a great hall at the Institute of Arts Rivera painted murals honouring the technology and the multiracial workers, and even the besuited boater-wearing managers and time-and-motion men, the technocrats. He captured the immense scale and complexity of the operation, all of it, and much more. He painted the car plant as the seething heart of industrial capitalism, a sort of supervised bedlam with its roots in history, and with branches reaching into lives in the furthest corners of the globe.

The plant was the epitome of modern capitalism, the car — stately, gleaming freedom machine and most desired thing — was not only the engine of the economy, the shaper of worlds and mighty creator of wealth, but the indispensable component of consumerism, capitalism’s core ideology. Good Marxist that he was, Rivera saw the contradictions and tempered admiration with foreboding, reverence with satire.

Pre-war, Detroit was in the vanguard of America’s burgeoning global pre-eminence. During the war, when the US became the self-styled “arsenal of democracy,” the car companies of Detroit flew the flag with gusto, manufacturing prodigious amounts of military equipment, from tanks and planes to artillery and ammunition. One Ford plant turned out a B-24 bomber every hour. Once the war was over, the combination of new models and smart advertising made Detroit not just an industrial engine room but a smart, desirable, essential American city.

When Henry Ford II (grandson of the original and known as “The Deuce”) took over the company in 1945, he set out to repair relations with Jewish Americans. He began in Hollywood, where the damage was illustrated by Harry Warner, who had forbidden any employee of Warner Brothers, including Gary Cooper, to drive a Ford on the company grounds. The Deuce also gave up his grandfather’s other, more visible means of gaining the “consent” of his workforce, the anti-union thuggery of the 1930s. In 1937 four leaders of the United Auto Workers handing out leaflets headed “Unionism not Fordism” were brutally beaten outside the River Rouge plant. In 1949, Ford and one of the victims of that attack, Walter Reuther, agreed to terms that became a model of collective bargaining, and a sign that capitalism could serve everyone’s interests. In return for the company providing full pension benefits, medical and hospital insurance and wages linked to inflation, the union contracted to provide five years of industrial peace.

Soon after, Chrysler and General Motors also gave up their union-busting and put their names to the agreement. It became known as the Treaty of Detroit. Fortune magazine wrote that the treaty “made the worker to an amazing degree a middle-class member of a middle-class society.”

Impressed by Roosevelt’s New Deal in the 1930s, Walter Reuther became an anti-communist social reformer — an American social democrat — and an irresistible (and incorruptible) force in both the union movement and the Democratic Party. In 1948 a shotgun blast through the window of his home put him in hospital for three months. He used the time to work out a better union medical benefits scheme.

As he took worker entitlements beyond wages and conditions into pension benefits, health insurance, early retirement and even profit-sharing, Reuther led unions into social reform, civil rights and national politics. He was pushing for the Peace Corps years before Kennedy made it a signature policy. In the early 1960s he urged the big three car companies to join forces and make a smaller, more economical American car. He was close to both Kennedy and Johnson and campaigned for civil rights, both in Detroit and across the country. Brimming with American optimism and bright ideas, Reuther, said one journalist, was the only man he knew who could reminisce about the future. In a parliamentary democracy he might have been elected prime minister.

Jeffrey Eugenides wrote that “most of the major elements in American history are exemplified in Detroit.” Race, immigration, the suburban dream, corporate power, class, capital and labour, dream and disillusion, corruption, crime. (The mafia was a persistent presence, but in what big city was it not?) No doubt the same could be said about a few other cities, but for a couple of twentieth-century decades no city came closer to embodying the American ideal.

A city of a million and a half people, a mighty manufactory with a spectacular waterfront business district, a powerful and progressive union movement; a young and popular Democratic mayor, Jerome Cavanagh, and a socially progressive Republican governor, George Romney; a city of art and culture from the Institute of Arts’ fabulous holdings to Motown, a cultural phenomenon founded by Berry Gordy, who modelled his music business on the Lincoln–Mercury assembly line where he’d worked. Motown was built on the talents of Black songwriters and performers like Smokey Robinson, Diana Ross and the Supremes, Marvin Gaye, Gladys Knight, Stevie Wonder and the Jackson 5. Yet for all their talents, under Gordy’s Quality Control, the artists were “a means to an end,” the end being the Motown sound. And roughly equivalent to Ford’s Sociological Department, Motown hired an “etiquette coach” to make the Black artists more acceptable to white audiences. It worked. Motown moved the world.

It also moved Americans, even southern Americans: when Motown artists performed in the South in the early days, the audiences were segregated, but a “common love for the music” changed things when they went back. “People wanted to dance,” Mary Wilson of the Supremes recalled. “But when they started dancing, they forgot where they were sitting. And that segregated audience became integrated.”

In 1963 the city that gave the world the Ford Mustang and Stevie Wonder united in a bid for the Olympic Games. President Kennedy came and enjoyed a tumultuous reception. Half a million, 40 per cent of the population, were Black. Martin Luther King led thousands on a Walk for Freedom down Woodward Avenue, flanked by Reuther, Cavanagh, Rosa Parks, civic leaders, union leaders and church leaders. George Romney would have joined them, but it was a Sunday and he was a devout Mormon. He sent a representative in his place, and a few days later attended a small civil rights march in the exclusively white suburb of Grosse Point.

Of course they don’t make Republicans like George Romney anymore, and if they did they would be political outcasts like his son Mitt. King’s speech turned out to be a rehearsal for the immortal version he gave at the Lincoln Memorial. He called Detroit “a herald of hope.”

In the same year, two sociologists at Wayne State University published a seventeen-page study called “The Population Revolution in Detroit.” Hardly anybody noticed, but their research discovered that, on “present trends,” the city would lose a quarter of its population over the next decade. Amid all the buoyancy and optimism, Detroit was already on the way down.

For years a steady stream of white people had been leaving the city for new satellite suburbs linked to downtown by new highways. After the riots the stream became a torrent. Stores closed. White workers, white businesses and white families deserted. They took their dollars with them, leaving the city with a rapidly shrinking tax base. The Black middle class followed.

Cars, which had made Detroit a great city, played their part in its fall. Cars being the future, nothing was invested in public transport. Who wanted railways when highways were the thing? Well before the riots, and well before manufacturers began moving their plants to China and Mexico, they had begun to move them to non-union towns. Then Toyota came, with its “lean,” “just-in-time” Toyota Production System. Soon the Camry would be the top-selling car in the country, American cars that had epitomised modernity became symbols of decline, and Fordism a relic of an earlier stage of capitalism.

Capitalism churned and governance churned with it. Corruption seeped into city hall, the administration and the (rapidly dwindling) unions. Detroit became a shrinking city of the poor, the poorly educated, the unemployed and the unskilled. A city of crime: corrupt in its high places, its streets plagued with violence, theft, arson, prostitution, drug dealing and addiction.

Today downtown Detroit belies all the above. The towers positively gleam. The art deco interiors are stunning. The streets are clean, the monuments well maintained. There are cafes and bars. A tram runs down Woodward, making it cheap and easy to get to the Institute of Arts, the Library and Wayne State. In a city notorious for crime, it feels remarkably… nice, if a bit like a museum. The people are not the unnerving part; it’s the absence of them.

A bar I found one evening was packed, and it had that feeling of fellowship which all good bars have. It was not a particularly big bar, but it seemed like the entire downtown population was there, and when I walked out onto the empty streets the sense grew stronger. Detroit seemed plain empty, and all the emptier for the acres of carparks where once there must have been buildings.

Had all the city workers swept home along the freeways? Or do they work from home anyway? Out the window of the hotel that night the buildings standing in their paddocks of concrete were lit in red, white and blue, but it felt like I was the only person looking at the show.

Drive beyond downtown and the story of Detroit unfolds in images of ruin. Streets lined with long empty, collapsing, weed-infested houses. Places that were once suburban blocks and home to countless families grown over with full-blown woodlands. Ghosts of streets where kids played, and their parents parked their Fords and Chryslers and lived their version of the dream.

Freeways being an American speciality, Detroit’s are impressive. They are brutal. Their builders made no compromise with people or with nature and now they evoke the same melancholy as the abandoned factories they barrel past. Some of the old industrial plants are getting a new life as apartments. Artists are moving in. Websites recommend tours of abandoned streets and factories — dress “post-apocalyptic chic.” Gentrification is coming to Detroit, but, at first glance at least, it’s not convincing.

“Detroit these days depends on the kindness of strangers,” says Steve Babson, a labour historian at Wayne State. He admires Joe Biden for his pro-labour, pro-union commitments, and for the social investment of “Bidenomics.” Gretchen Whitmer, the Democratic governor of Michigan and probable presidential aspirant, he thinks “okay,” but she is, he says, another corporate liberal, a term he prefers to neoliberal because there is nothing “neo” about the idea of governments doing the bidding of capital.

It is not just the prospects for corruption of individuals, parties, cities and democracy itself. Even if the relationships were between parties of impregnable integrity; even if we accept that converting wealth into power is inevitable in a progressive capitalist democracy and needs to be managed rather than discouraged; and even if corporate endowments and investments were sufficient to rebuild cities and communities, how can it be done without replicating the imbalances of wealth, power, education and amenity that destroyed them? By calling his program “Build Back Better,” Biden at least seems to have grasped the nature of the problem.

Detroit was the definitive American city, the pinnacle of American innovation and industry. For a city like Detroit to fail was more than a disaster, it was a humiliation for the country. American capitalism and American society broke down simultaneously, making the city that symbolised greatness a symbol of failure, an engine of hope, an engine of despair. If you want to know America, know Detroit. If you want to fix America, fix Detroit. •

This is an edited extract from High Noon: Trump, Harris and America on the Brink, Don Watson’s latest Quarterly Essay, published by Black Inc.