Paul Cinquevalli has two show stoppers. The first is to catch between his supple neck and powerful shoulder a spinning cannon ball, released from a net high above him. He got the idea while practising a trick with a stick and a big wooden sphere, which fell on his neck without hurting him. When he changed to a metal ball, the unruly object “got tired of the job,” and when he persisted “it got nasty and finished up by knocking me out.” He recalls lying unconscious for an hour. But the accident only increased his will — iron on iron — to make the feat work.

Perfected over a year, it soon becomes an audience favourite. In Sydney, during his 1909 tour of Australia with Harry Rickards’s Tivoli circuit, he is given a friendly warning: “Well, it seems to me that the game is not worth the candle. If you miscalculate the ball by half an inch it will probably kill you.” “Dare say,” quips Cinquevalli, with his mild central European inflection, “but you see, I never miscalculate.” In fact, an onstage slip in London had left him concussed. But he is dauntless.

That reservoir of assurance equally girds Cinq’s second, more intricate, crowd-pleaser. He balances one billiard ball, then another, on the thick end of a cue; with his free hand, he lays the rim of a wine glass on his upturned forehead. He raises a third ball onto the base of the glass, then lifts the balls-and-cue onto the ball-and-glass-and-man combo, so the whole spire rests on his brow. Now, with the merest flex, he topples it. Result: cue in right hand, glass in left — and a ball in each of his three shirt pockets.

This breathtaking trick takes Cinq eight years to “lay hold of,” as he has it. Hard enough to imagine as a one-off, it yet allows for many variations. In the most elaborate, earning him the tag “human billiard table,” he wears a tunic made of green billiard cloth with six cord-and-wire pockets. “[In] a moment billiard-balls run over his back like mice, billiard-cues assume the blind obedience of sheep,” writes a critic of the art. “You leave the theatre conscious that the English language does not contain adjectives big enough for Cinquevalli; and later you try to explain what he is to your friends and fail miserably. He must be seen to be understood.”

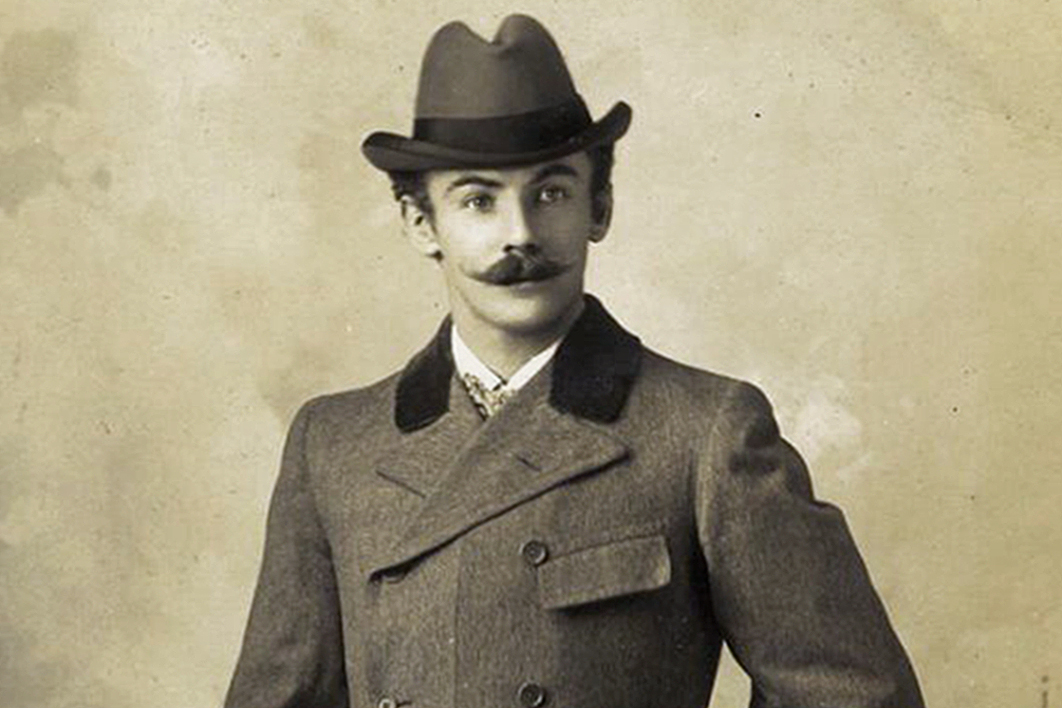

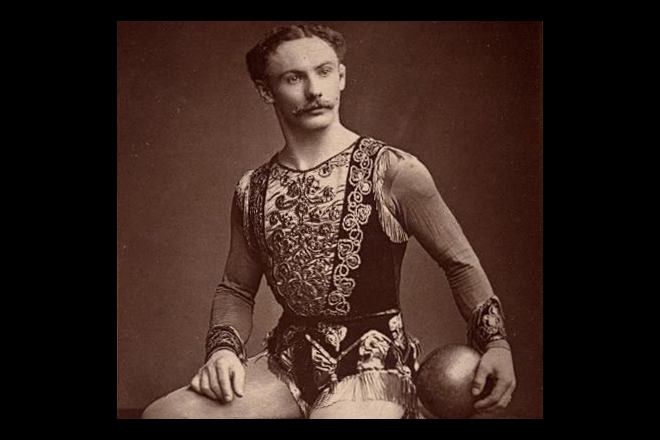

The art of apparent simplicity: Cinquevalli in costume, from a London Stereoscopic and Photographic Co. postcard.

There are other spectacular turns in Cinq’s fluid repertoire. Dressed in waiter’s garb, he launches into flight a tray, a teapot, a cup, a saucer and a sugar cube, landing them from their dizzying dance in nanosecond synchrony to pour and serve. Now flaneur, he makes the tip of a whirling lemonade bottle lock onto the rod of a circling umbrella, in that instant opening the canopy and spraying liquid over it. He stands underneath, nonchalantly holding the handle, the bottle zipping into his coat pocket.

All entertainers require pinpoint accuracy in some form, though few risk real danger with a misstep. For Cinquevalli these hazards are at the heart of a performance repeated, but each time with electric immediacy, night after night. Behind his supreme artistry on the theatre and music hall boards is invisible daily discipline, a healthy regimen, mental alertness, muscular power, a hunger to improve and intense competitiveness. “A machine wants oiling, and practice is my oil,” he tells Adelaide’s Advertiser on that same tour. By then, he has been on the road for thirty-six years, and would stay another five.

In a world driven by imperial and industrial might, connected by steamship, train and telegraph, his career encompasses Odessa and St Petersburg, New York and Cape Town, Paris and Delhi, Mexico City and Singapore, London and Melbourne. Ballarat and Broken Hill too, for he goes where the people are. Paul Cinquevalli is the pioneer world-crossing showman of the modern age.

“I have hardly a trick that has not its own story”

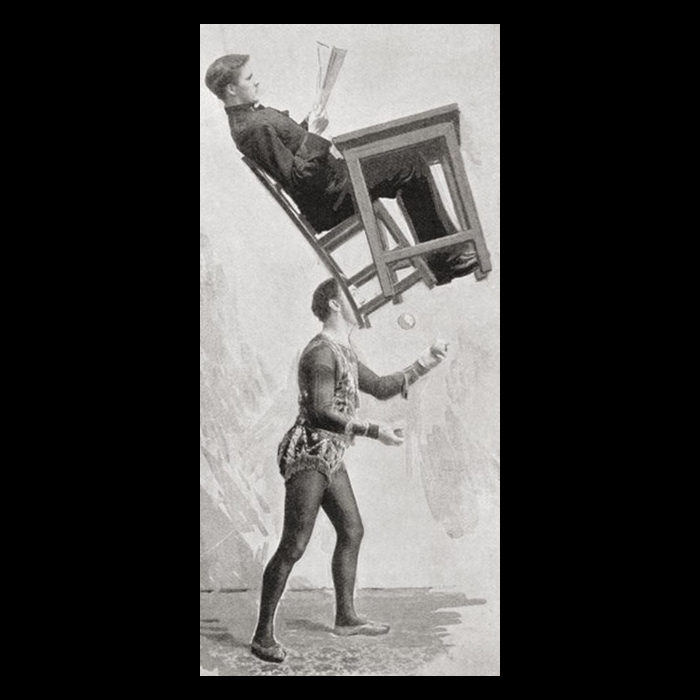

During four decades he caresses, tosses and balances myriad objects in countless combinations: pencil and slate in childhood, and egg and plate, graduating to knife, fork, potato, torch, chair, bathtub and telephone. (The chair can include a newspaper-reading assistant, at a desk, the whole lifted by Cinquevalli’s teeth — as he juggles three balls.) His ideas turn materials into planets, careering around a galaxy of his own creation. It is apt that his professional self-description is, at different times, entertainer and dramatic artist, for a mixture of this kind goes to the heart of his appeal. “When I find that I have an imitator I just invent something else,” he says. Even when answering the variety-goers’ call, Cinq — like Bob Dylan it might be said — is always pushing at the boundaries of his own inspiration.

He knows his effect, studies it, cultivates it. Adaptation to evolving tastes is one source of his longevity. A feigned threat to the orchestra leader from an airborne billiard cue opens a vein of comedy, enriched by the arrival of his talented onstage foil Walter Burford (“whose face bespeaks humour in itself,” observes another critic). Pantomime roles in Aladdin and Puss in Boots alongside the virtuoso of melancholy Dan Leno puts his “incomparable conjuring” in the service of knockabout humour. On any stage, says a witness, “he had the art of apparent simplicity — the art that conceals art, and conceals, also, a world of careful and painstaking preparation.”

“When I find that I have an imitator I just invent something else”: one of Cinquevalli’s most remarkable feats shown in a sketch from an 1897 edition of the Strand Magazine.

The most interesting person in the world is the one who speaks with keen insight about his or her own craft. Cinquevalli is right up there, his focus on the eye not the object a lesson in aerodynamics. “The whole secret lies in receiving the impact of the ball in a slanting direction,” he says. “The idea is to break the fall of the object, and then to bring it to a stationary position immediately. It is well done in the fraction of a second, quicker than the eye can really follow, and a practically invisible twist at the finish effects the climax. The slightest miscalculation though…”

His wry precision infused with Mitteleuropa flavour is a bonus. (“I have hardly a trick that has not its own story.”) The knack extends to gripping yarns of touring across Russia’s western empire with the circus troupe he has run away to join, several times brushing with death. In one story, having volunteered to fix a canopy high up on a narrow ledge with no protection, the young aerialist survives a vertiginous fall. In another, its setting Kherson in Russia-ruled Ukraine, he recounts the players’ ambush by bandits intent at best on extortion of their proceeds: “The robbers found themselves attacked in turn by a pack of huge wolf hounds. Our people also kept up a brisk fire from shelter upon the attackers, being careful of the lives of our canine comrades… In the end we secured eight prisoners, more or less peppered by our gunfire, and torn by the dogs. Our casualties were two dogs killed and one wounded.”

Cinq’s stories, light on heroics, exude sparkle and cordiality. There is no cynicism in him. The details tend to fit, even when recalled many years apart. True, the oil of practice may be at work, along with a degree of self-promotion when the audience is a journalist. Equally, a lifetime’s need of exactness may come into play. Cinq is not an illusionist or conjuror, impressing by clever deception. (“Everything I appear to do I do. There is no pretence.”) His physical qualities — balance, dexterity, coordination, strength, delicacy — are mesmerising enough. That they are dinkum, the work of immense dedication, is central to his being and to the public’s esteem. In “Cinquevalli,” an endlessly beguiling poem, Edwin Morgan writes: “There is no deception in him. He is true.” On stage, in the realm of art, few doubt this. Off, in life, it is nowhere near as certain as it could once have seemed.

“The best kind of Englishman”

“He is vague about his antecedents and birthplace, but it matters less where he has been than where he is going, and that would seem to be straight up.” Cinquevalli’s reception as a travelling performer in London in 1885 has a forehint of a twenty-year-old Bob Dylan playing in a New York folk venue, as spotlit by Robert Shelton’s landmark review. Though only twenty-five, Cinq arrives with an apprenticeship of twelve years in Europe’s imperial metropolises and provinces. From an unusual background, he emerges as a cosmopolitan with national allegiance to a Poland erased from the map in the 1770–90s.

His early life, as far as an account based on the more reliable sources can reach, holds political flight, a melange of social orders and languages, a cause unwon, an acrobatic education, a dice or four with mortality, and the discovery of a new métier. Such experiences might have produced a gifted writer, educator, entrepreneur, diplomat or politician. If the young Emile Otto Paul Braun becomes instead an entertainer, it is of a type that somehow always contains more than a trace of possible other lives.

A son of Poles, born in 1859 in the east Prussian town of Polnisch Lissa, his direction was shaped by conflict. His father, a miller of black bread turned cloth merchant, is of German origin yet a patriot for Poland, a nation divided between Russian, German and Austrian empires and already a veteran of doomed revolt. The blowback from a major new uprising in 1863, having cost Braun’s father his livelihood, sees the family in Russian territory and fearing Cossacks at the door.

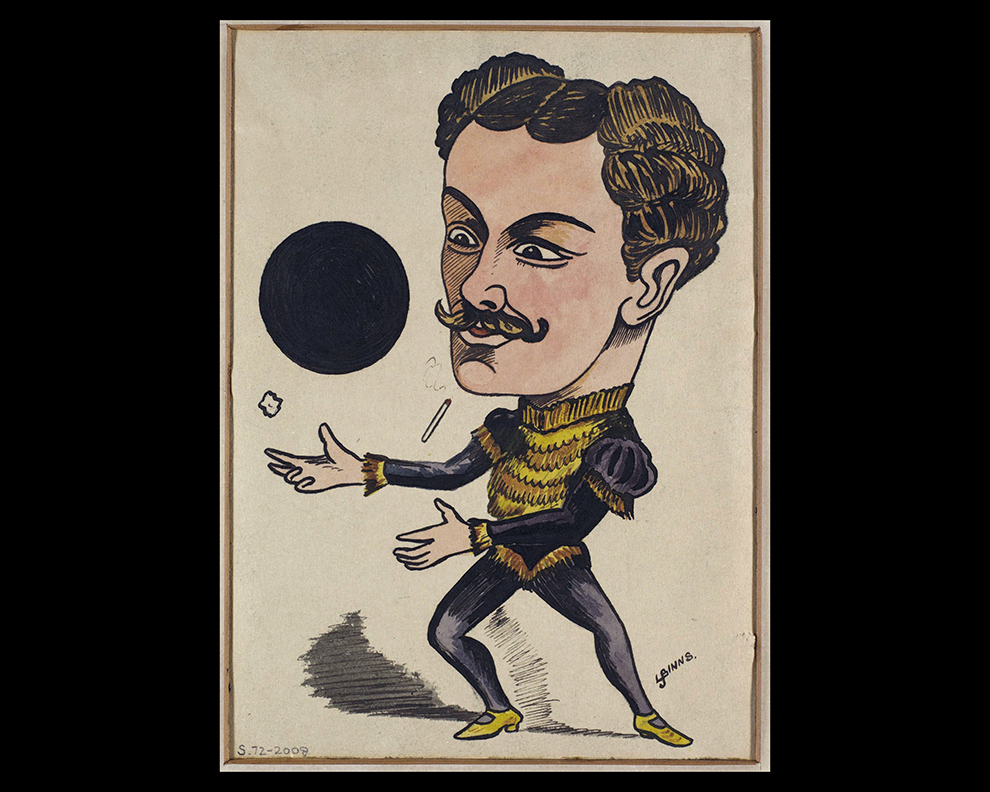

“A revolution in juggling tricks”: cartoon by L.J. Binns showing Paul Cinquevalli juggling a large black cannon ball, a lump of sugar and a lit cigarette, around 1905. Victoria and Albert Museum

“My people had mixed themselves up in politics. It was foolish of them,” he recalls in Sydney half a century later. “But in those days every Pole had visions of a united country, free from the shackles of tyranny. They rose in arms and cursed the government at every opportunity. My father and my uncle were marked men. It was particularly necessary for them to get out of Russian Poland as fast as they could.” An escape via Warsaw and Łódź to Görlitz, just across the Prussian border, brings safety.

As a prize-winning local gymnast at school in Berlin, Paul is talent-spotted by the Rome-born circus leader Giuseppe Chiesi, then nearing sixty, whose troupe is composed of three “families” styled Chiesi, Bellon and Cinquevalli. Enthralled by the dashing Italian’s acrobatic display, and offered a performing role, he chooses the freedom of the road in face of parental opposition. “[At] last I determined to run away with my tempter. Our first journey took us five days, from Berlin to Odessa, and I went through as the son of M. Cinquevalli.” He is thirteen years old.

The budding “aerial gymnast” is performing in the Black Sea port when a weight of snow collapses the tent and sends him into a freefall checked by a woman in the audience. She dies; he lives. An eventful debut tour around Russia’s empire climaxes with acclaim at the theatre of St Petersburg’s zoological gardens, where canny marketing promotes him as the “little flying devil.” One night, he slips on a rung left undried after rain. The plunge to the ground — 70 feet or more, says Cinq — means more broken bones and eight months in hospital, where a war for life and against boredom marshals his whole life force into, and dozens of objects through, his sinuous free hand.

His left wrist permanently damaged, there is no way back to the trapeze. But Cinquevalli, now taking his itinerant patron’s adopted name as his own, always looks ahead. “The fluke of my life,” he calls the St Petersburg accident, for it jolts him towards using “the ordinary things of life” as material for “a revolution in juggling tricks.” His comeback in the same arena proves memorably confusing and moving, when instead of applause he is greeted by an immense silence. “Understand, I had been treated as a public favourite up to the time of my fall.” Then, as an orchestra completes a national hymn of thanksgiving, the vast crowd kneels and makes the sign of the cross. “I was completely overcome, and broke into tears.”

The Dylanesque twists of fate continue. Roaming Europe with Chiesi’s circus, the novelty of Cinq’s “portmanteau” approach to juggling strikes a chord. In Berlin the performers impress Wilhelm I, the Prussian king and future German emperor, the attendant publicity facilitating reconciliation with his parents back in Lissa. Playing in his home town ends in humiliation via an unbidden exchange in Polish: while he is disguised as a baboon and tasked with jumping through a hoop studded with knives, his mother cries from the audience: “Don’t do it, Paul! You will be killed!” His instinctive response: “It’s all right, Mama!” The derision is total and the retreat from Lissa swift.

Chiesi’s caravans reach Paris, Vienna, Copenhagen, Stockholm, Rome itself. In each capital, the veteran’s glamour and younger bloods’ exotic appeal ensure a royal imprimatur. London, having the self-assurance to patronise foreign novelty without caring about its provenance, offers the troupe a benign entrée. Cinquevalli’s second appearance there, in late December 1885, is by command of the Prince of Wales, future King Edward VII, who is dazzled by his miraculous feat with a wooden block, razors and rolled newspaper. “Good fortune seemed to fall on me in volumes,” Cinq says of the period, and a Janus-faced stroke adds one more.

A sojourn of eight weeks in London is scheduled to end with a return to a leading circus in St Petersburg, obliging him to refuse “flattering offers,” until news comes of a major fire at the venue. He remains at the London Pavilion for over a year; his mentor Chiesi returns to Russia’s capital, where he dies in 1887. Cinq adds the English language — “the greatest conundrum on God’s earth” — to his collection, improves his mandolin and piano playing, explores photography, mesmerism, mnemonics, motor transport and everything new. (“If there is something I do not understand, I lie awake at night puzzling over it.”)

Cinquevalli becomes naturalised as British in 1893, and often says that he is “the best kind of Englishman,” given “it is a deliberate choice after considering the claims of other nations.” In 1904 he reflects on that early time: “I began to get an idea of what English home life is. After five years in England I went back to Russia, and to my surprise I felt an utter stranger. When I landed again in London on a fearfully foggy morning I felt somehow that I had come home.”

“Who could not like a country like this?”

Cinquevalli’s own effect upon England in the mid 1880s is seen in two near-instant expressions of public regard: plaudit and metaphor. Theatre posters and journal advertisements soon declare him to be “the greatest juggler in the world” and “the wonder of the world,” borrowing Paris’s accolade “L’incomparable.” Through the rollicking era of music hall, 1890–1914, when the topical merits of gutsy variety stars are tested amid a heady social commingling, he continues to justify the extravagant billing.

Turning forty at the century’s end, he allows no let up. In demand from the Americas, Ireland, continental Europe and South Africa, he makes his first visit to Australia and New Zealand in 1899, playing to appreciative houses. A witty Melbourne Argus review of his last night at the Bijou Theatre concludes: “Mr. Cinquevalli’s neatness, quickness, and extraordinary cleverness, both with heavy weights and with trifles light as air, evoked enthusiasm, and he was rewarded with thunders of applause.” The tour forges real bonds. “I like Australia,” he says on the 1909 tour, the third of four. “Who could not like a country like this? Not only the place and the climate, but look at the audiences and how they treat me.”

In the wake of those first two London performances, Cinquevalli-as-emblem flowers in step with encomium. A political journalist quips that “in the old election days [Cinquevalli] might have gained a fortune by teaching parliamentary candidates how to catch rotten eggs on the hustings without breaking them.” In doing so the sketch writer hoists a balloon into an amusing if capricious flight, which peaks in Cinq’s heyday and stays aloft long after his death in July 1918.

As a byword for virtuosity, Cinquevalli’s name is attached to French aviators, Scots soccer players, cricketers W.G. Grace and Ranjitsinhji, the pianist Paderewski, hospital pathologists, aeroplane engineers, a Covent Garden basket-carrier in a Pathé news clip of 1925, college girls exercising good posture in another of 1930, and dozens more. The latest instance so far recorded is from 1978, although by then it is the ghost of someone else’s memory. A curiosity of the inexorable ebbing is another poem, also called “Cinquevalli,” published in 1957, several years before Morgan’s, by a new Bristol writer, Millicent Falk, aged seventy-five. Contrasting herself to the juggler’s wilful play of objects, she writes: “But I / Did not begin any game, seldom can choose / Anything, yet must take what comes / To handle each like him with speed and deftness.”

The stock allusion is politics, in particular money-juggling chancellors, whose Cinq-echoing exploits are also a cartoonists’ resource. But his third of six mentions in Australia’s parliament, in 1945, comes in a tangle on wool promotion between two children of the 1890s. The Country Party’s Joe Abbott, describing Cinquevalli as “the greatest conjuror, juggler and master of deception” in the country’s history, who “with a twist of the wrist, could turn cannon balls into canaries,” branded the austere minister for postwar reconstruction, John Dedman, his “lineal descendant.” Cinq’s rebuttal is decades old: “I am sometimes referred to as a conjuror, but I am not. A conjuror deceives, but a juggler does everything he claims to do.”

Leaving aside that Cinq is in fact an expert conjuror, if only in private for his friends’ delight, the story of such references is an inevitable descent into cliché and then anachronism. But like other peerless exponents of a craft or sport, Cinq kindles that rare thing, genuine awe. In 1906, the prolific author E.V. Lucas, admittedly a devoted admirer, calls him “the very Shakespeare of equilibrists,” able to “[neutralise] the life-work of Sir Isaac Newton with exquisite grace and lightheartedness.” He confesses: “In talking about Cinquevalli to an artist — and a very level-headed artist, too — after the performance, he said, before I had mentioned this peculiarity of mine, ‘I must go and see him again. But the odd thing about Cinquevalli is that he always makes me cry.’” The bestselling novelist Arnold Bennett also reaches for the summit: “I have in turn been convinced that Chartres Cathedral, certain Greek sculpture, Mozart’s Don Juan, and the juggling of Paul Cinquevalli, was the finest thing in the world.”

With equal inevitability the panegyrics, as responses to an uplifting live presence, would lose their force, and survive only as archival angel dust. A bleaching of memories is accelerated by the immense social and psychic changes of the Great War, which begins as Cinq is in Australia on a final tour before his planned retirement. That leaves only sparse, scattered documents to hint at his genius, and his capacity to elevate as well as divert. Most perceptive is the Glasgow poet, born in 1920, who sees in a sepia postcard image a “bundle of enigmas”:

Half faun, half military man; almond eyes, curly hair, conventional moustache; tights, and a tunic loaded with embroideries, tassels, chains, fringes; hand on hip

with a large signet-ring winking at the camera

but a bull neck and shoulders and a cannon-ball

at his elbow as he stands by the posing pedestal;

half reluctant, half truculent,

half handsome, half absurd,

but let me see you forget him: not to be done.

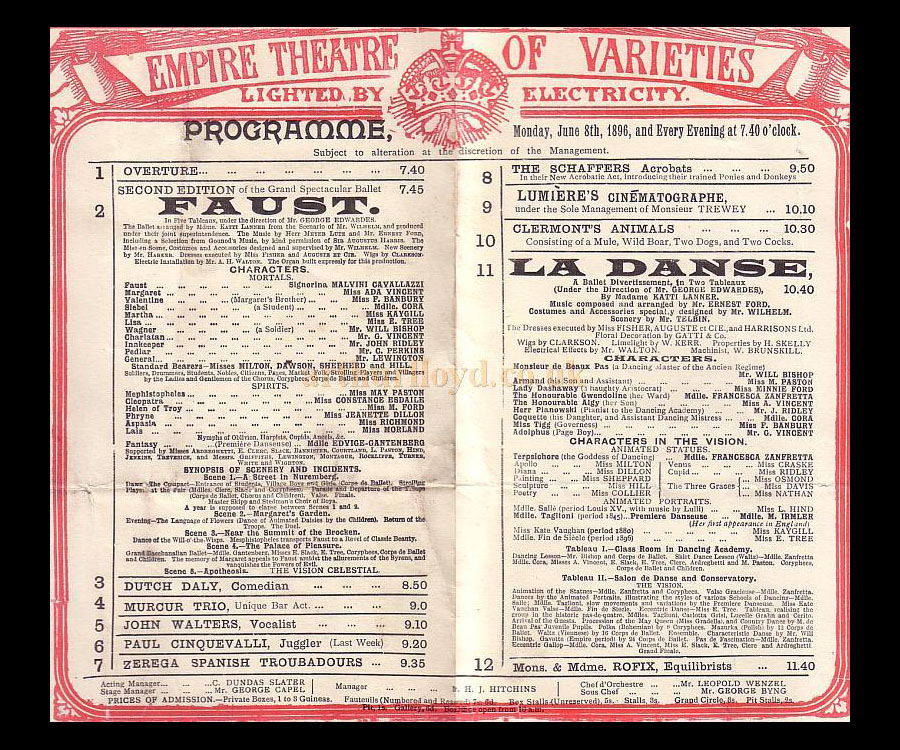

Other vagaries bear on Cinquevalli’s amnesiac afterlife. Early cinema jostles with theatre and music hall, and frequently makes them its subject matter. But Cinq is uncaptured by the emerging form, though he promotes the Kinetoscope and then Vitascope (a device overtaken by the Lumière brothers) and even performs on the variety bill at one of Britain’s earliest commercial film screenings, in Leicester Square in 1896.

Jostling forms: Paul Cinquevalli, listed near bottom left, on the bill for one of Britain’s first commercial film screenings

Charles Chaplin gazes at Cinq’s heights from his own start-up, the Lancashire Lads; half a century on, he conceives his late film Limelight, with its hollowed-out star Calvero, as a homage. At its preview, Chaplin tells guests of a lesson passed on direct from his boyhood idol. At first, Cinq makes his billiard balls trick look too easy, and receives no applause. “Learn first to make it look impossible,” he is told. “Learn to fail a few times. Then they’ll appreciate you.”

For all such overlaps, to posterity the real Cinquevalli is at most an indistinct shadow of the brimming late Victorian and Edwardian stage: far behind Marie Lloyd, Vesta Tilley, or Dan Leno — let alone Chaplin himself — in the memory stakes of a long faded and sentimentalised world.

Cinq’s modest forecast, shared with an author friend in England at the time of his retirement, turns out to be prescient: “I shall not be missed, only a name. Paul Cinquevalli, juggler — would that I could have made it more worthy of being remembered when I am gone. Nobody is any the better for having seen me; others will take my place, and the crowds who today cheer me in the halls will pass me by in the street, without recognition.”

“I am leaving my two best friends”

The filtering starts early and reaches far. A ubiquitous, unexamined notion about Cinq’s late years, for example, is that revelations of his German ancestry sweep into the surge of anti-German prejudice after the war’s outbreak in 1914, leading to attacks on his home, professional banishment, enforced retirement, withdrawal from society and a forlorn death. No shred of contemporary evidence is ever adduced in support of these claims, which feed endlessly on themselves even unto the Dictionary of National Biography, museum collections, and many works on music hall. As a whole, this ever-recycled and inflated story amounts to a convenient, self-reinforcing myth that fastens Cinquevalli’s desiccation.

An influential outline appears in 1920, when the journalist H.G. Hibbert publishes A Playgoer’s Memories. “His death was one of the little tragedies of the war. In spite of his Italian name, he was a Teuton, German or Austrian, born Kestner, although world wandering in infancy had robbed him of all homing instinct… His one loyalty was to his calling, and when the vulgar instinct of the people to whom his charity had been his religion made a pose of ostracising him, it broke his heart.”

Once set, the template allows for many overlays. The doughty Yorkshire-Jewish writer Naomi Jacob writes in her 1933 memoir, Me, A Chronicle About Other People, that when the war begins, “no one worked harder to get money for charity than Paul Cinquevalli.” But “some of the charming people who were jealous of Cinquevalli spread the rumour that he was not a Pole, but a German; that he was a spy, and a dozen other ridiculous and abominable things.” The “very fine and gallant heart” of this “gentleman” — “Yes, I know it’s a misused word, but not when you apply it to Paul Cinquevalli” — was crushed.

A surfeit of allusions, Edwin Morgan’s too (“‘Keep Kestner out of the British music-hall!’ / He frowns; it is cold; his fingers seem stiff and old”) might suggest a flicker behind the smoke rather than mere self-confirmation. Extensive, if by no means exhaustive, study is yet to find it. Perhaps worthy of note is that the most thorough histories of anti-Germanism in Britain during the period make zero reference to the celebrated entertainer, Paul Cinquevalli.

The earlier versions on which the edifice is built invite a conjecture. In wartime, the entertainment world’s icons — Marie and Vesta and Harry Lauder, shrewd retailer of cosy Scottishness — lead philanthropic efforts for the boys at the front. Cinq’s own enduring generosity to variety causes and colleagues is well attested. In 1912, witnessed by King George V and Queen Mary, he tops the bill in the first Royal Variety Show, combining royal patronage of music hall with charity fundraising. That amid chauvinist excesses, a few industry begrudgers seize a chance to burnish their jingoistic credentials by exposing Paul “Kestner” is feasible. Even malicious gossip, little known beyond a coterie of insiders, might do the job. When the ugly moment passes, a shamed silence descends and no trace survives.

But some figments of the processed tale already wither on even basic inspection. Cinq gives his last British performance in New Brighton, near Liverpool, on 20 June. The Tivoli manager announces this at the curtain call, before Cinq himself speaks. (“All things must come to an end.”) It is national news: “Cinquevalli retires,” says a headline in the Birmingham Daily Mail, which reports his “anxiety” at the prospect. He then sails to Australia for a sixteen-week tour, this time under the aegis of Rickards’s flamboyant partner-successor Hugh D. McIntosh, playing his final show in Melbourne on 15 December, almost five months into the war. Again he bids farewell from the stage: “I am beginning to realise now that I am leaving my two best friends — my work and my audience. But it is better that I should leave them, than that they should leave me.”

Such details, complemented by the press’s routinely positive references to Cinquevalli during the war (though there are of course many fewer), counter the formulaic version of his last years. Alone against a stifling orthodoxy, an article in the excellent Australian Variety Theatre Archive, published in 2014, expresses scepticism about what “appears to be a matter of mass replication from an unidentified secondary source (or sources) that erroneously assumed his retirement was a result of the war.”

The cataclysm thwarts a likely permanent move to Australia and definite plans to explore Japan, a land that has fascinated him at least since 1886, when he appeared with the juggler Katsnoshin Awata and decorated his flat in Soho’s Gerrard Street à la Japonaise. Beneath the “huge Japanese sunshade of many colours, which swings to and fro with the slightest breath of air,” an enthralled guest had hailed the twenty-six-year-old as “a universal genius.” The world described was young, full of accomplishment and the promise of new morning. Now, back in his south London home, four decades of world-crossings are over. Cinq’s adjustment of his mode of living is inevitable.

“I had always curiosity with patience”

Paul Cinquevalli is newly retired, and fifty-five. He muses on the fact that men in his family rarely live much beyond sixty. And he does not disappear. A Times reporter encounters him in the St James’s Club in 1916, lunching with his American comrade, the pantomimist Paul Martinetti. In gregarious mood, Cinq is rueful about his increasing weight. In 1917, he plays (and loses) a charity snooker match at The Ring on Blackfriars Road, a characterful boxing arena — yet another passion. He sees daughter Margot win a prize for a photograph featured in Amateur Photography magazine. In the midst of convivial life, on a summer Sunday evening on 14 July 1918, during a party with friends around the piano at the family home in Brixton, south London, he has a seizure and dies.

The obituaries are admiring and regretful, without undertone. The theatre industry weekly, the Stage, evinces a genuine sense of bereavement. It refers to “deep regret throughout the variety profession” at the loss of a figure “greatly esteemed and respected by his brother and sister artists,” who moreover “was in his usual health and spirits right up to the last moment” — a point evidenced by a staff representative who had met Cinq at the Vaudeville Club days earlier. Paul Cinquevalli’s “proud position was attained and held not only by his supreme qualities as a performer, but also by his sterling qualities as a man.”

The disregard of such contemporary sources means that a life whose later stage happens to be conterminous with the war is still also forfeit to it. An unfortunate result is that many aspects of Cinq’s career, including episodes that channel his social instincts, get scarce attention. During the turbulent Edwardian era, 1901–11, he is sympathetic to lower-paid colleagues of the kind who participate in the music hall strike of 1907, and sardonically rebuts the claims of theatre proprietors in court when charged in 1910 with breach of contract.

Defending his non-appearance at a venue when his droll assistant Walter Burford falls ill, he swats the notion that Burford’s role is inessential. “But the public want to see you, and not the assistant?” “No, many come to see the assistant.” “Your modesty does you credit.” “There is no modesty about it. Some people like a laugh.” Cinq wins the judgement, with costs. Sadly, Burford’s death from epilepsy in 1909 had ended their partnership.

Cinq also supports the right of the black American world boxing champion Jack Johnson to play in Britain in 1913, following Johnson’s conviction for transporting a white woman across state lines (a verdict annulled in May 2018). The issue splits Britain’s theatre world. “I sympathise with Johnson,” Cinq replies to a Daily Mail round-up of views. “He is one of the sweetest natured and largest hearted men I know, and I think he has been treated very badly on account of his colour.”

Cinq’s intriguing associations beyond the variety world include the Birmingham professor Joseph Mee Hubbard, innovator of gymnastic education in England, and participant in the city’s pre-1914 debates between militarist and holistic uses of drill. In the war’s early days, he reflects on “magnetic” London: “Many people who live in the West End have never seen the Mile End Road and the slums. Of course there are slums and dire poverty, as there are in every large city. There is also an enormous amount of charity. But it seems as if the charity needs to be differently directed, for such huge sums as are given should work some good result.” This is a man always looking outwards, and with his own eyes.

His foresight about Poland is an example, albeit that the country would endure other travails in the “short twentieth century.” His first remarks when coming ashore in Australia and reading the cables from Europe are of confidence about his homeland’s recovery of independence. Cinq does not live to see that become reality in November 1918, nor to see his home town renamed Leszno; thus his whole life is spent loyal to a nation without a state. But his memoir of the 1863 revolt, composed in September 1914, qualifies patriotic romance with mature realism. Today’s Poles are “an artistic, industrious race… In the terrible days they have passed through, they have learned a great deal. They will emerge a diplomatic nation, and will fill that gap on the Continent which is so much needed.”

These are but a few of Cinquevalli’s multitudes. He seems to keep them all in balance. He is constant and animated. Always in transit, always practising alone in a room. A life at extremes, an observed rule of moderation in all things. Driven and competitive, urbane and collegiate. A refined artist who likes the common people. A man of modest bourgeois tastes and egalitarian instincts. A commercial head, generous with money. A restless innovator of fixed routines. A risk-taker in work, protective at home. Confident and illuminatingly self-aware (“I had always curiosity with patience”). When you stray far enough into his orbit, there is no way back.

“Are you not sorry for me?”

It’s some relief, then, to encounter discordant notes. Those lovely curls are a wig, for Cinq is bald. Journalists avoid the topic, which recalls the assertion in a 1984 book that Cinq — like other top stars it seems — might give press favourites a jewel as part of an unspoken contract. A gossipy memoir of a Liverpool vaudeville agent published in 1932 recounts a conversation about the billiard balls feat. “There is a heap of virtue in a tiny rubber ring,” an enigmatic Cinq is quoted as saying. Diarists cite his sharpness in patenting the multi-pocket tunic. Vanity, bribes, conning, self-seeking? Looking closely and in context, none adds up to much, but the hunt goes on.

In the republic of jugglers there is broad if not universal consensus over his pre-eminence. Though good timing has a role in making him an innovator, most see his combination of skills as unsurpassed. That the dynamic Russia-born Enrico Rastelli, hero of the 1920s, has more influence on later practitioners is itself a sign that Cinq stands apart. In juggling forums, however, citizens do still puzzle over how Cinq does the billiard balls trick. E.V. Lucas’s answer may never be bettered: “This feat I am convinced is as much of a miracle as many of the things in which none of us believe. It is perfectly ridiculous, after seeing it performed by Cinquevalli, to come away with petty little doubts as to the unseen world. Everything has become possible.”

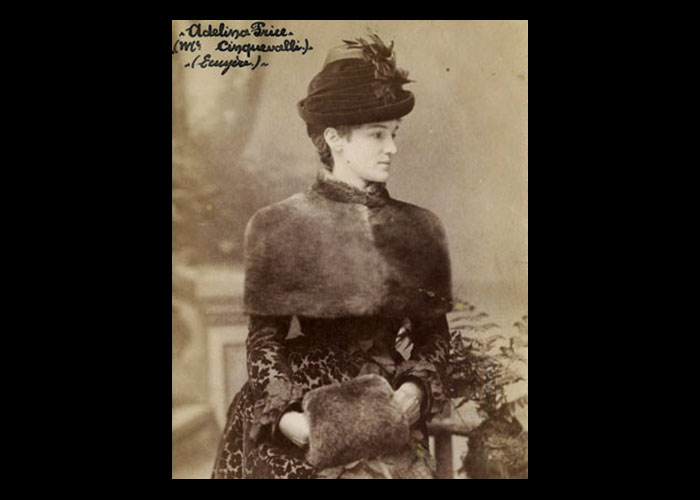

Of another order is Cinquevalli’s part in a dire episode, hitherto unrevealed, that raises unimagined qualms. Outwardly his family life is as proper, if also as beset by misfortune, as his career. In 1888 he marries Agrippina Alexandrine Adelina Price, a Moscow-born friend from their St Petersburg days, two years his senior. Adelina is a graceful equestrienne who performs with the most renowned companies in the golden era of the “horse spectacle”: Franconi’s Cirque Olympique , Cirque d’Eté, Circus Renz.

Golden-era performer: Adelina Price, who married Cinquevalli in 1888. Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée

They settle in St John’s Wood, north London, then tour in the United States on a working honeymoon, with Adelina performing at Barnum’s circus. A disabling shoulder injury for Cinq sparks a two-year move to Berlin, where he works as director of the Reichshalle theatre. An unfulfilled spell turns fortuitous amid the complicated birth of their son, Adolph Paul Frank, in 1890, when a renowned doctor saves mother and child, then enables Cinq’s recovery with crucial advice. This arrives by way of Professor Sondberg’s chance visit to Cinq’s office. “He saw a picture of me in my professional dress, and the secret was out that I had been a performer.”

In March 1893 the family is installed at a new home in Brixton, suburb of London’s theatreland. A visiting correspondent finds happy domesticity. “A small boy of three years old, in a quaint mixture of English, French, and German, begs to be allowed to show monsieur what he can do. He turns a neat somersault or two, and then lies on the hearthrug while, with a single sweep, Cinquevalli, senior, swings him into the air, the little fellow alighting on his father’s outstretched hand. ‘And do you propose to make an acrobat of him?’ asks the visitor, moderately hopeful as to his own security in the arm-chair. ‘If he wishes, yes,’ says M. Cinquevalli. But I would not force him.’”

In a sunlit front room hung with fine tapestries, a relaxed pyjama-wearing Cinq is the very paterfamilias. “For myself, one big trunk would suffice [to live],” he says, “for I love to be free to travel, but there is my wife and this chap. They must have a home, and so I settled in London.” All is set fair in a harmonious household, it seems. But the walls at Mostyn Road are also lately witness to a racking scene.

In mid 1892, as “Frankie” turns two, his twenty-two-year-old nursemaid Blanche Hines, who joined the family at St John’s Wood in April 1891, becomes pregnant. She later says that Cinquevalli seduced her two months after her start, on an evening when Mrs Braun had gone to the theatre, and that the relationship continued in Paris when the family moved there for one of his engagements. Blanche leaves his employ in July, and returns briefly in August before quitting for good. In December she exchanges telegrams with him about her condition. Adelina then calls on her residence at Chelsea’s Cheyne Walk and gives her a gold coin. When Blanche and Cinquevalli meet in January, she tells him that without his help she must go to the workhouse. There follow payments from him for her upkeep, the cash given each Monday evening at the West End venue where he is performing.

When the child, named Fernand Paul, is born in March 1893, Blanche’s sister Lena — a tailoring worker from Cambridge — visits Mostyn Road to press her sibling’s case, meeting Paul and Adelina together. “I wish to help Blanche,” Lena quotes Cinquevalli, “and I will give her a character [reference] to get a situation, but if I give her money that will be an acknowledgement.” In Lena’s account, he then leaves the room, returns with a purse, takes out a £5 note, passes it to Mrs Braun, who hands it to her, saying: “Are you not sorry for me?”

A court orders Cinquevalli to pay five shillings a week for the child, near the wage of a domestic servant, from birth to the age of sixteen. There is bare reportage, with no follow-up or public scandal. Blanche raises Fernand, who prefers to be known as Paul, in London and then the eastern county of Suffolk. They each find secure employment, the latter in public administration, marry on the same day in 1916, and live to a grand age. The fate of the noble Lena is so far uncharted.

The routines of life and work go on. But in 1895, a weekend family trip to the countryside during Cinquevalli’s residency at Paris’s Folies Bergère brings tragedy. After lunch, Frankie’s body sprouts dark blotches: enduring hours of acute pain, and given castor oil by a local doctor, he dies. Food poisoning, impure medicine, an undiagnosed malady? “Le mystère du Epinay,” as L’Écho de Paris ’s bleakly meticulous report calls the event, has no definitive solution. The loss coincides with Adelina’s thirty-eighth birthday. A year later almost to the day, the couple’s daughter Marguerite Pauline (Margot) is born in London.

A common feature of both painful chapters — with much unknown — is that neither evidently disturbs Cinquevalli’s engagements and tours, his quality of work or its reception. If his behaviour is indelibly flawed, his resilience and professional appetite are remarkable. They would be required again when Adelina succumbs to cancer in 1908, leaving the eleven-year-old Margot motherless. A year later Cinq marries Dora Nowell, a thirty-one-year-old London-born sculptor, in Woollahra. She and Margot survive him, as does the loyal Czech-Austrian retainer Marie Horacek, integral to the household for two decades, a modest beneficiary of his will, and — after years living with Dora — buried in the family grave.

There is, after all, deception in him, though what it consists of and means, exactly, to those embroiled, how it plays out in their own lives, and how far it goes: these are high in the air. A full biography is needed, perhaps a good novel too, to bring them into fuller sight.

You too, Cinq?

In the context of everything I thought I understood about Paul Cinquevalli, this discovery — a “You too, Cinq?” moment — brings visceral awareness of the impenetrable mystery that is any human heart. More prosaically, it poses new questions about him, and equally about the women in his life. If this interim effort to de-mummify Cinq may unwittingly add a few sealants of its own, the results of further historical inquiry can only be enlightening. In any event, a cloudburst of proper recognition is long overdue.

A Britain soaked in sentimentalist anniversaries might be expected to notice the centenary of the death of the world’s first entertainment superstar, but beyond the Friends of West Norwood Cemetery’s upkeep of the family monument, and murmurs of an English Heritage blue plaque at Mostyn Road, there is nothing. In one way that is obliquely welcome: as if even now Cinq’s complexity resists the blandifying compulsions of heritage, and holds out for serious treatment. In another it might reflect his protean nature: as if the “universal genius,” like the neighbourhood cat, is claimed by no one in particular. (A small example is the fact that Polish libraries tend to classify him as Niemiecki, or German.) More intimately, it serves to confirm his quicksilver aliveness: as if the man who contains everything remains himself uncontainable.

The notion echoes Morgan’s closing lines:

Cinquevalli’s coffin sways through Brixton only a few months before the Armistice.

Like some trick they cannot get off the ground

it seems to burden the shuffling bearers, all their arms cross-juggle that displaced person, that man

of balance, of strength, of delights and marvels, in his unsteady box at last into the earth.

Weather records for the day note unseasonal “hailstones the size of pigeon-eggs” over the area. Paul Cinquevalli goes out with a last show stopper, and a celestial salute. A century on, this wondrous figure is still out of reach. ●