Republican candidate Donald Trump and Democratic aspirant Bernie Sanders have both been labelled populists. So have the left-wing Occupy Wall Street movement and the right-wing Tea Party, along with Marine Le Pen, Geert Wilders and an array of other far-right European party leaders. So too was Venezuela’s left-wing president Hugo Chávez, as well as heads of government as different as Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the Philippines’s Rodrigo Duterte.

That list tells us two things: there’s a lot of it about, and it seems to cover an astonishingly wide variety of leaders and movements.

In political commentary, populist is often a derogatory term, excusing the writer from giving a person or a party any serious consideration. It is popular at the Australian, where it has been used to criticise Labor’s calls for a royal commission into banking and its opposition to tax cuts for big business. When the Gillard government called a royal commission into institutional sex abuse in 2012, the headline on Paul Kelly’s column called it a “depressing example of populist politics.”

While “populist” comes from the same root as “popular,” it elicits a very different value judgement: popular good; populist bad. But how are the two linked? Isn’t all democratic politics populist? Isn’t being responsive to public concerns and outlooks a democratic virtue? Passing judgement by calling something populist – even when it’s an accurate description, unlike Kelly’s headline – is no substitute for explaining it.

Part of the problem lies in the concept itself. Populism cuts across the usual ideological constructs of left and right, which rest on different views about the role of the market and government. Populism is anti-market, especially in its hostility to free trade, transnational corporations and “money power.” In American parlance, it is pro–Main Street and anti–Wall Street.

In the past, populist movements were often agrarian, attracting farmers whose struggles against the vagaries of the seasons were compounded by the fickleness of the market. They felt entitled to a fair price for the labour they had invested in the production process, and resented the seeming arbitrariness of broader economic forces. Reflecting these contending pressures, populism often seems to support government intervention, explicitly or implicitly, yet resents bureaucratic interference and red tape, and views welfare recipients with suspicion.

Populism may be a useful concept for explaining the activities of economically nationalist governments in the Third World, or the appeals that dictators use to extend their powers in countries with fragile democratic institutions. But it is not always helpful to think that everything labelled populist is sufficiently similar to come under one umbrella. Here, I’ll focus on contemporary right-wing populist movements in economically advanced and politically stable democracies.

In practice, analysts generally reserve the term “populist” for two types of conventional electoral politics. One involves politicians who try to pit a unified “people” against outsiders – migrants, minority groups, terrorists and so on – using essentially symbolic gestures that demean or threaten outsiders, like the Turnbull government’s toughening of the process for immigrants to become citizens.

The other brand of conventional populism is practised by politicians who pander to misconceptions among segments of the population or urge courses of action they know will be ineffective. Populists can be simultaneously in favour of increased government spending and lower taxes, for instance. A trivial example of this kind of populism was Kevin Rudd’s promise during the 2007 election campaign to launch a website called Grocery Watch, which was designed to dramatise the fact that Labor shared the public’s concern about cost-of-living pressures. The party no doubt knew that it would have little effect on prices, and in the event it was quietly dropped a year or so into government.

The sterility and cynicism of mainstream political debate in Australia is depressing in itself, and contributes to the growth of populism. But full-blown right-wing populism goes well beyond the frustrations of party politics by adopting four key elements.

The in-group versus the out-group: The central characteristic of all populism is the sharp division between us and them. As Jan-Werner Müller writes in his recent book, What Is Populism?, it sets a morally pure and fully unified people against all others, whether they are elites or foreigners or other enemies of the people. The view that the people speak with a single voice makes populism anti-pluralist. If “the people” have a common interest and outlook, then dissent can easily be portrayed as disloyalty or betrayal.

This leaves populist rhetoric with the problem of extracting “real people” from the total sum of the citizenry. Nigel Farage, leader of the UK Independence Party, called the Brexit referendum a “victory for real people,” as if the 48 per cent who voted to remain were not real. Right-wing Republican populist Sarah Palin used to refer to the “pro-America areas of this great nation.” The populist strand of the Republican Party called itself the Tea Party, after the Boston Tea Party of 1773, a pivotal moment in the build-up to the American war of independence, yet the modern Tea Party is pitted not against British colonialists but against its fellow Americans.

Upward, downward and outward resentment: The main animating force of populism is anger. Its proponents are determined to confront forces that threaten or betray “the people.” Betrayal by the “elites” – the perfidious and corrupt wielders of self-seeking power – is an ever-present motif.

Donald Trump encapsulated this theme in his inauguration speech. “Today we are not merely transferring power from one administration to another…” he said. “We are transferring power from Washington, DC and giving it back to you, the people. For too long, a small group in our nation’s capital has reaped the rewards of government while the people have borne the cost. Washington flourished but the people did not share in its wealth.” During the campaign he had argued that “the establishment, the media, the special interests, the lobbyists, the donors, they’re all against me. I’m self-funding my campaign. I don’t owe anybody anything. I only owe it to the American people to do a great job.”

While disgust with elites is a recurring motif in populism, at least as important is hostility to outsiders, especially immigrants. In 1996, Pauline Hanson was primarily aggrieved by Aborigines and by the Asian migrants who were allegedly swamping Australia; by 2016, her primary target had shifted to Muslims. What remained constant was her need for an alien enemy. Among the elderly Britons and others who voted for Brexit, studies found that the common thread was hostility to immigration and the fear of even greater immigration to come.

“The people have borne the cost”: a Trump supporter in Washington on inauguration day. Joe Flood/Flickr

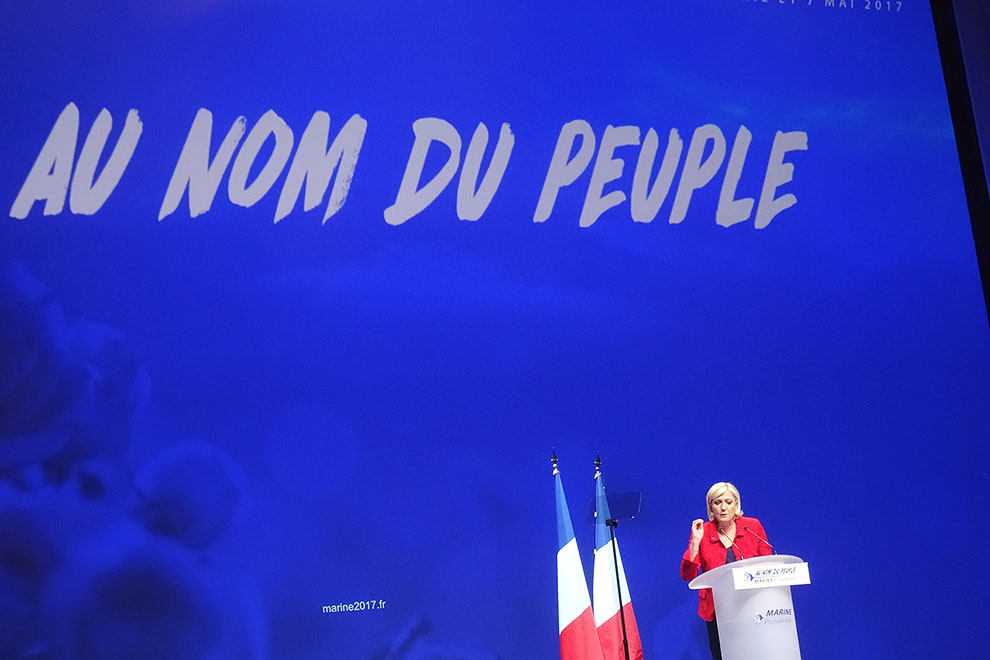

In France and several other West European nations, similarly, immigration has been the major target for the populists, gaining momentum from the association of a small number of Muslim immigrants with terrorism. Immigrants are seen as a security threat, and are blamed for crime and economic difficulties: in a simple equation, the French National Front declares, “Two million unemployed is two million immigrants too many.”

Less obvious than upward and outward resentment is downward resentment. Supporters of populism are not usually from the very poorest sectors of society, and while many populists support the welfare state, they are often also hostile to those they see as undeserving recipients, including unemployed people and refugees. Often, too, weaknesses in the welfare state are blamed on the usual targets: thus, Marine Le Pen asserted that “they are pulling out all the stops for the migrants, the illegals, but who is looking out for our retirees?”

Only in the United States is a more sweeping disapproval of the welfare state still apparent. “You are not entitled to what I have earned,” declared one bumper sticker. Journalist Mark Danner quotes one Trump supporter describing himself as a member of “the white working class in America. The ones paying for all the others. Finally we’re getting someone who’ll do something for us.”

Hostility to debate and democratic processes: Populism transforms the complexities and ambiguities of the contemporary world into a search for enemies and culprits. This allows its proponents to argue that simple solutions championed by strong leaders are the answer. Their policy prescriptions are liberated from the real world of trade-off and compromise, of limited resources and unintended consequences, to the realm of simple solutions obvious to anyone with common sense. All that is needed is strong leadership; further debate is unnecessary, and simply a means of avoiding action.

Populists often use simple, strong slogans – “Make America Great Again,” or the pro-Brexit “Take Back Control” – to avoiding discussing specifics or to discredit critics. British Conservative minister and Brexiteer Michael Gove used the most sweeping dismissal: “People in this country have had enough of experts.”

As Jan-Werner Müller argues, populism is inherently hostile to the mechanisms and values of constitutionalism. It is scornful of the need for checks and balances, of the protections and inhibitions that stem from due process. It often manifests an impatience with – and even a disdain and disgust for – proper procedures and conventions. The judges in Britain who ruled unanimously that Brexit could only proceed with parliamentary approval were labelled “Enemies of the People” by the Daily Mail.

Bad manners

In the most nuanced and comprehensive of the recent books on populism, The Global Rise of Populism, Benjamin Moffitt argues that we need to move from seeing populism as a particular set of policies, and view it more as a political style that thrives on crisis and confrontation. Populists have succeeded in shaping the public agenda and generating media attention, often by going outside or defying political conventions – by being provocative and aggressive, for example, and trying to generate a sense of crisis and scandal. Donald Trump was a “chaos candidate,” Jeb Bush complained, as the insurgent’s tactics unbalanced the other Republican contenders.

The political scientist Pippa Norris has observed that Trump and his allies introduced a new “brutalism and intolerance, altering what’s speakable in American politics.” Populists nearly always resort to coarse and culturally vulgar appeals, says Moffitt, swearing and directing offensive taunts at opponents. (Marine Le Pen has accused political rivals of being paedophiles.) Their followers often see this coarseness as plain-talking, which cuts through the suffocating inhibitions of political correctness to tell it like it really is. Offensiveness becomes proof of authenticity, says Moffitt; other politicians are seen as self-seeking and hypocritical. In Australia, as Moffitt reports, political scientist Sean Scalmer found people who saw Hanson as a “dinkum stirrer” bringing views shared by many Australians into the public realm.

It is often said that populism comes as a response to crisis. But populists have an interest in fomenting a sense of crisis, Moffitt argues. They need to show that politics-as-usual is failing – that the country is out of control and needs to change direction. This can be seen, for example, in Trump’s use of false data to exaggerate the crime problem in the United States. Populists also seek to create an aura of drama around themselves, as was on bizarre display when Pauline Hanson made a video that included the words “If you are seeing me now, it means I have been murdered… You must fight on.”

So populism isn’t just a case of more politics as usual. Nor is the answer to “bad” populism “good” populism. A left-wing Alan Jones isn’t the answer; it is a political discourse that doesn’t reward the Joneses. The key – much more easily stated than achieved – is for political debate to become more grounded in the real options facing societies, and for clashes between parties to be disciplined by empirical realities.

Is populism the way of the future? Especially since the victories of Brexit and Trump, the seemingly irresistible rise of right-wing populism has been a running story in the media. This narrative downplays several counter-examples. Justin Trudeau won a smashing victory in Canada in 2015 on an economically progressive and culturally tolerant platform. In May last year, Londoners made Sadiq Khan their mayor, the first Muslim and candidate from an ethnic minority to be so elected. Earlier this year, Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party was expected to win 15 per cent of the vote in the WA election, but support fell to just over 8 per cent in the electorates her party chose to contest. In Austria last year, many expected to see the election of the country’s first far-right president; in the event, the victor was a Green. And just last month, many Dutch voters were fearful that the party of the far-right Geert Wilders would sweep the country; on election day, it increased its vote slightly to win twenty of the 150 seats, fewer than it won in 2010 or that its forerunner won in 2002.

Yet both the Dutch and Austrian elections show a splintering of political support and significant disillusion with the established parties. In the Netherlands, the top three parties together won 85 per cent of the vote in 1986; by 2017, the figure was just 45 per cent. In Austria, the most interesting aspect of the presidential election was the collapse of the centre. In the first round of the election, the two parties that have dominated postwar Austria and provided every president, the Social Democratic Party and the Austrian People’s Party, each polled just 11 per cent of the vote, trailing not only the Freedom Party and the Greens, but also an independent. This splintering of loyalties brings a greater likelihood of legislative deadlock; mixed with increased polarisation, it is a recipe for continuing political frustration and more populism.

For these reasons, populism surges, but usually its support will soon collapse. Distaste for major parties, and for politics as usual, drives people to populist parties, rather than any intrinsic appeal of their own. Once these parties are under scrutiny, it becomes clear that they are usually unable to articulate or defend their policies. Much depends on the leader, the one who claims to embody the people’s will: it is often his or her newsworthiness that thrust the movement into the media limelight.

Not only are their feet commonly made of clay, but they also often run their parties in an authoritarian manner and become prone to defections and internal discontent. Since Pauline Hanson’s party returned to prominence last year, it has been plagued by disputes and disaffections. “I’ve been in this for twenty years and to have a new kid on the block telling me what to do is absolutely ridiculous,” Hanson said during her contretemps with the soon-to-be-disqualified One Nation senator Rod Culleton. In fact, far-right parties (like their mainly defunct left-wing counterparts) appear to have an inherent tendency to split. Crikey’s Bernard Keane has listed ten different and often-squabbling far-right groups active in Australian politics.

What this all demonstrates is that right-wing populism is a far-from-irresistible force. History shows that its surges are often followed by collapses. Given the dysfunctions in current politics and ongoing economic stresses, though, it is likely to keep disfiguring democratic politics for some time, and to have a disproportionate influence on policy and public debate. •