In November last year a young German woman created headlines when she took to the stage during a rally against pandemic restrictions in Hannover. “Hello, I’m Jana from Kassel,” she began. “And I feel like Sophie Scholl because for months I have been active in the resistance, given speeches, attended demos, handed out flyers.” She said that she too was twenty-two years old, just “like Sophie Scholl when she fell victim to the National Socialists.”

The video depicting Jana’s short speech went viral, and her reference to Scholl was widely reported — and mostly condemned. The German foreign minister Heiko Maas was among those who weighed in, accusing the young protester of playing down the Holocaust and “mocking the courage” it took for Scholl to oppose the Nazi regime. Even the state parliament of Lower Saxony was prompted to debate Jana’s choice of words.

Sophie Scholl and her brother Hans were caught on 18 February 1943 at the University of Munich distributing leaflets calling on fellow students to rise up against the Nazis. The pamphlet was the sixth written by Hans Scholl and his friends, the members of group called the Weiße Rose (White Rose), who had been circulating their leaflets — mainly anonymously to randomly selected addresses — since June 1942. The Scholls and their friend Christoph Probst were tried for high treason on 21 February, convicted and beheaded the same day. Three other members of the group were sentenced to death two months later.

For postwar Germany, the Scholl siblings, perhaps more than anybody else, represent the “good Germans” who stood up against the Nazis. Around 600 streets and 200 schools have been named after them. Their lives are depicted in an opera and in numerous books, plays and feature films, including Michael Verhoeven’s hugely popular film The White Rose (1982), Percy Adlon’s Five Last Days (1982) and the Oscar-nominated Sophie Scholl: The Final Days (2005).

The looming anniversary of Sophie Scholl’s birth on 9 May 1921 has prompted the release of four new biographies. Already, the weeklies Spiegel and Zeit and many daily newspapers have published lengthy articles re-evaluating her life and afterlife. German Post is issuing an 80 cent stamp — the fourth German stamp to commemorate her, after releases in 1961 in East Germany, 1964 in West Germany and 1991. The hashtag @ichbinsophiescholl enables Instagram users to follow the last ten months of her life. And 9 May itself will feature commemorative ceremonies, a church service (broadcast live on radio) and online theatre performances and readings.

The further the present is removed from Scholl’s past, in fact, the more her fame has grown. In 2003, her bust was included in the Walhalla, a hall of fame created by order of the nineteenth-century Bavarian king Ludwig I. She has arguably become the most famous woman in German history.

Jana from Kassel was not the first to invoke Sophie Scholl during the protests against the pandemic restrictions; her attempt to liken herself to Scholl was merely the first to become front-page news. In September last year, the prominent Covid-19 denier Alexandra Motschmann restaged the scene that led to Sophie and Hans Scholl’s arrest in 1943, throwing leaflets from the top floor of the University of Munich’s main building. (Thanks to cinematic representations of the Scholls, the image is easily recognisable among Germans.) Elsewhere, people protesting against the government’s policies carried white roses or placards with photos of Sophie Scholl or quotes attributed to her. Three weeks before Jana’s speech went viral, Covid-19 protesters in Munich organised a commemorative ceremony at the cemetery where the Scholl siblings are buried.

The Covid-19 protests have attracted an odd mix of people: from esotericists and anti-vaxxers to followers of the populist right-wing Alternative for Germany (Alternative für Deutschland, or AfD) and others on the far right. The latter have been invoking Sophie Scholl for some time: marking her ninety-fifth birthday, for example, leading AfD politician Beatrix von Storch quoted her in a tweet: “Many are thinking what we said and wrote. But they don’t dare to articulate it.” In 2017, a few months before the national elections saw the AfD win more than 12 per cent of the vote and enter federal parliament for the first time, the party’s South Nuremberg branch posted an image of Sophie Scholl on its Facebook page with a quote taken from the first leaflet of the White Rose: “Nothing is as unbecoming for a civilised nation as to let itself be ‘governed’ willingly by a ruling clique that acts irresponsibly and is driven by dark instincts.” This was accompanied by the line “Sophie Scholl would have voted AfD.”

At the other end of the political spectrum, too, Scholl has her admirers. When asked recently to name her heroes, Greens leader Annalena Baerbock, potentially Angela Merkel’s successor after the national elections in September, listed Scholl first. Carola Rackete, the Seawatch captain who rose to fame in 2019 when she defied Italian interior minister Matteo Salvini’s order not to enter Italian territorial waters with rescued refugees, tweeted in February: “If #SophieScholl was alive today I am pretty sure she would be part of local #Antifa organising.”

Sophie Scholl is not the only prominent member of the German resistance whose legacy has been appropriated by right-wing populists. She is not even their favourite. The figure who most interests the AfD is Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg, born in 1907 into a noble family that traces its roots to the thirteenth century.

Stauffenberg had embarked on a career in the military as an eighteen-year-old. On 20 July 1944, by then a colonel in the German army, he tried to assassinate Hitler at Wolfsschanze, his military headquarters in East Prussia, by placing a bomb in a room where he was meeting with his generals. In the ensuing coup d’état coordinated by Stauffenberg, units of the German army would then have taken control of government facilities. Hitler survived, the coup failed and Stauffenberg and four other conspirators were executed on the same day. Others of the plotters were tried by Roland Freisler’s Volksgerichtshof (People’s Court), which had also convicted the Scholls; in all, about 200 of the conspirators were executed or committed suicide.

The anniversary of the attempted assassination is commemorated every year in Germany, and often the president or the chancellor gives a speech to mark the occasion. A memorial museum was established in 1968 at the site where Stauffenberg and his fellow conspirators were executed by firing squad. The “men of 20 July” have featured in history textbooks no less prominently than Sophie and Hans Scholl have done. Stauffenberg, in particular, has been the subject of numerous books, documentaries and feature films, including Bryan Singer’s 2008 Valkyrie, which starred Tom Cruise as Stauffenberg.

In February this year, the AfD tabled a motion in federal parliament proposing that a memorial museum be built at the former Rangsdorf airport (about twenty-five kilometres south of Berlin) to commemorate Stauffenberg, who departed from that airport on his assassination mission. The move is designed to highlight the party’s opposition to the country’s official memories; the motion condemns a “memorial politics” that is “increasingly determined by doctrinaire positions and interests and often pursues the cultivation of a feeling of guilt.” The AfD has long claimed that all past events are now viewed from the perspective of German guilt and demands that Germans ought to focus instead on positive achievements, on heroes rather than on villains. Stauffenberg would be one such hero.

One of Stauffenberg’s admirers is Alexander Gauland, the co-leader of the AfD’s parliamentary party in the Bundestag. A lawyer by training, he fancies himself as a historian and has written books about Germany’s recent and distant pasts, including a history of Germany since the early Middle Ages. For Gauland, Stauffenberg is a reminder of German might and glory: with his attempt to kill Hitler and end the war, “one last time, the magic of the [House of] Hohenstaufen [lit] up German history.” In Gauland’s reading of Germany’s past, the age of the Hohenstaufens — emperors including the twelfth-century Frederick Barbarossa and his grandson Frederick II — was the high point of German history, when the German empire’s reach was unrivalled.

Brave, principled, young and good-looking: Tom Cruise as Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg in Bryan Singer’s 2008 film, Valkyrie. Allstar Picture Library/Alamy

At the same time, Stauffenberg was a “true conservative,” according to Gauland, and could be linked to what was termed after the war the Conservative Revolution, a group of writers and thinkers who initially sympathised with the Nazis but later distanced themselves from them. Both Gauland and Björn Höcke, who for some time have been the two most influential figures within the AfD, have drawn on representatives of the Conservative Revolution when trying to define their intellectual home.

The commitment to commemorate Stauffenberg also allows the AfD to draw a line between themselves and the “old” far right and neo-Nazis who sing the praises of Adolf Hitler and his henchmen. This has become a litmus test to distinguish between acceptable and unacceptable radicalism within the AfD. Asked in a 2019 interview whether there were any red lines that an AfD member must not cross, Gauland responded: “There’s a limit to freedom of speech in the party. You can’t say that Stauffenberg was a criminal and traitor.” A former state leader of the AfD’s youth wing, who had indeed called Stauffenberg a traitor, was swiftly expelled from the party.

Finally, and here the AfD’s appropriation of Stauffenberg and the Covid-19 deniers’ instrumentalisation of Sophie Scholl converge, Stauffenberg is an attractive historical figure because he is defined by his resistance. Höcke and the more radical elements within the AfD believe that resistance (against a hegemonic “system”) is their right and duty. So do those attending the weekly Pegida demonstrations in Dresden who carry a flag once designed for a post-fascist Germany by Josef Wirmer, a lawyer involved in the 20 July plot and executed in September 1944.

The anniversary of Stauffenberg’s failed assassination attempt has been commemorated since 1946. But unlike Sophie Scholl, Stauffenberg is an often controversial figure who has not always been given full credit for his attempt to end the war. That scepticism was already evident in the Western Allies’ unenthusiastic response to the coup attempt. In early August 1944, Winston Churchill characterised the plot as a manifestation of an “internal disease.” He told the House of Commons, “The highest personalities in the German Reich are murdering one another, or trying to, while the avenging Armies of the Allies close upon the doomed and ever-narrowing circle of their power.”

In early postwar West Germany, Stauffenberg and his co-conspirators were often considered traitors. In communist East Germany, their resistance was overshadowed by that of members of the Communist Party. From the 1980s, the annual 20 July commemorations in West Germany have similarly stressed that it would be wrong to privilege the resistance within the German military, because there were many others who opposed the Nazis and paid with their lives for their acts of courage.

It probably took Tom Cruise in the role of Stauffenberg to win over non-German publics to the cause of the conspirators of 20 July 1944. By contrast, the Allies readily applauded the Scholls and their acts of resistance already during the war. A few weeks after their deaths, the New York Times reported their trial and execution on its front page. In June 1943, the Red Army distributed a leaflet behind the German lines that described Probst and the Scholls as “noble and courageous representatives of German youth.” The authors of the leaflet made no attempt to turn the Scholls into proletarian internationalists; in fact, Hans Scholl was quoted as having said, “I am not a communist. I am a German.”

In June 1943, Nobel Prize–winning German writer Thomas Mann honoured the Scholls in one of his monthly Deutsche Hörer! radio addresses, which the BBC broadcast via long-wave transmission to Germany: “Brave, marvellous people! You shall not have died in vain. In Germany, the Nazis have built monuments for dirty rascals and common killers. The true German revolution will tear them down and in their stead immortalise your names. When Germany and Europe were still covered in darkness, you knew and announced: ‘A new belief in freedom and honour is dawning.’” A month later, the Royal Air Force dropped a propaganda leaflet with the text of the sixth pamphlet, titled “Manifesto of the Munich students,” over Germany.

Thomas Mann’s prediction turned out to be accurate. The names of the Munich students were immortalised, although some names more than others. That process began immediately after the end of the war, when the German writer Ricarda Huch collected material about the students and publicised their story. Huch’s work was continued by Hans and Sophie’s elder sister Inge, who published a book about the White Rose in 1952. For decades, her interpretation of the lives of her siblings and their friends dominated the public reception of the White Rose, at least in West Germany. Her portrait of Hans and Sophie showed two people whose destiny it was to sacrifice their lives in the fight against Hitler. But their deeds were also celebrated in East Germany, as if continuing the approach taken by the authors of the Red Army leaflet dropped behind German lines in 1943.

Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg met some of the prerequisites for a hero. He was brave, principled, young and good-looking. The fact that he was unsuccessful counts for little: as is expected of heroes who fail in their quest, he sacrificed his life. But other attributes make him less suitable for the role. In communist East Germany, his being a member of the aristocracy and a high-ranking officer in the army, and holding conservative political views counted against him. In West Germany, many initially objected that Stauffenberg had not only violated his oath as a soldier but also played into the hands of Germany’s enemies at a time of war. As time went by, his status as a high-ranking professional soldier became a further liability after it became widely known that the German army had been implicated in the Holocaust.

Critical questions have been asked about the timing of the coup. Why did he and his fellow conspirators wait for so long before acting? Hadn’t they long known about Auschwitz, Treblinka, Sobibor and other death camps and the mass killings of Jews in places such as Babi Yar? Hadn’t they seen first-hand how the German army mistreated the civilian populations of Poland and the Soviet Union? Had it not dawned on them much earlier that something was fundamentally wrong with the Nazis’ racialist ideology? Had they perhaps been hoping for a German victory, and acted only once it had become clear that the war was lost?

At least since the 1980s, the “men of 20 July” have been viewed critically also because most of them did not envisage a democracy replacing the dictatorship. Some of them had only contempt for the Weimar Republic; some were hoping for a return of the monarchy. They fought the good fight mainly because of who their enemy was, and not because of what they were fighting for.

Some also held against Stauffenberg the fact that he was afraid to sacrifice his own life — that he left the room after placing the briefcase containing the bomb under a table and immediately returned to Berlin, rather than making sure that the dictator had been killed or, even better, killing him himself. Some even considered Stauffenberg incompetent and thought he had botched the opportunity to assassinate Hitler.

But although Stauffenberg was not without his flaws, the story of 20 July has centred more on him than on the others involved in the plot, who included Social Democrats and other civilians who wanted democracy to be restored. This focus makes sense because Stauffenberg’s role was crucial. Not only was he the one who planted the bomb; more than anybody else he was responsible for the network of allies and sympathisers within the military, without whom the coup would never have succeeded even if Hitler had been killed. It fell on him to coordinate the plot — which is why it would have made little sense for him not to return to Berlin once the bomb had been put in position. Nevertheless, the spotlight on Stauffenberg has meant that the contributions of others may have received less attention than they deserved.

While it’s obvious why the story of the attempted coup has paid particular attention to Stauffenberg, it is less evident why Sophie Scholl has come to personify the resistance of a group of Munich students. The first four leaflets of the White Rose were produced in June and July 1942. They were jointly written by Hans Scholl and his close friend Alexander Schmorell, the son of a Russian mother and a German father. Both had served at the Russian front and been deeply affected by that experience. When they began writing the leaflets, they were both studying medicine at the University of Munich.

In July, Schmorell and Scholl were once more sent to the Eastern front. They returned to Munich at the end of October, committed to continuing their resistance against the Nazi regime. It was only then that they began involving others: Christoph Probst and Willi Graf, two other medical students; the musicologist Kurt Huber, who taught at their university; and Hans’s sister Sophie. The fifth and sixth leaflets, produced in January and February 1943, were written by Hans Scholl, Schmorell and Huber.

Curiously, Schmorell’s and Huber’s contributions are barely remembered today, and Hans Scholl appears to have been dwarfed by his younger sister, who is now sometimes imagined to have been the group’s driving force. When German president Frank-Walter Steinmeier marked the seventy-fifth anniversary of the failed coup of 20 July 1944, which is now used to commemorate the German anti-Nazi resistance more generally, he referred to “the group around Sophie Scholl.”

The fact that Schmorell’s contribution has been neglected could probably be attributed to Inge Scholl’s role as authoritative interpreter of the White Rose. She simply, and understandably, privileged the contributions of her siblings. The reasons why Sophie outshines her brother are more complex. I believe there are two main factors, and they are related.

The first is that she was the youngest and the only woman in the group. In postwar Germany, there has been little enthusiasm for the traditional male hero, the slayer of dragons and saviour of damsels in distress. That’s partly because Nazi propaganda created an abundance of them, and partly because, in our post-heroic times, female heroes who don’t seem to care about their status are considered less problematic than their testosterone-driven male counterparts. Think of Greta Thunberg or Malala Yousafzai or Emma Gonzalez or Loujain al-Hathloul, for example — or, in Germany, Carola Rackete. Male heroism has largely been reserved for sportsmen: for Helmut Rahn, who kicked the winning goal in the 1954 World Cup final against Hungary, or Franz Beckenbauer, who in the Game of the Century against Italy during the 1970 World Cup kept playing with an injured shoulder.

Second, Sophie Scholl also fitted the role of an innocent victim much better than her brother. When remembering Nazi Germany, Germans have preferred to focus on the fates of victims, perhaps hoping that they too could be mistaken for victims rather than perpetrators or their descendants. Nobody’s fate has prompted a greater outpouring of emotion than that of Anne Frank, but she is remembered as a Jewish rather than as a German girl. (It is often forgotten that she was born in Frankfurt.) Sophie Scholl was both an Anne Frank–like victim and a good German whose sacrifice could provide some redemption for a nation with a bad conscience. She could be a hero, but one with the attributes of a saint.

Hans and Sophie Scholl were prepared to pay the ultimate price for their acts of resistance. They did so believing that their actions would have a major impact. They also thought that the fall of Stalingrad, which happened a couple of weeks before their arrest and informed the text of the sixth leaflet, meant that the war was almost over. In the long term they were proven right, but not in the short term. Their lack of judgement betrayed their naivety.

If Stauffenberg’s bomb had killed Hitler, the coup might have succeeded and the war ended nine months earlier. Millions of lives might have been saved. But even then, the intervention of the “men of 20 July” would have come too late for many, including Jews, Sinti and Roma, and all those others murdered in the countries occupied by Nazi Germany. Nevertheless, the assassination attempt of 20 July 1944 was arguably more significant than the distribution of a few hundred leaflets seventeen months earlier, if only because of what could have been, rather than because of what eventuated.

In terms of what could have been, however, the most significant act of German resistance took place well before Stauffenberg and the Scholls recognised the full horrors of the Nazi regime. On 8 November 1939, thirty-six-year-old Georg Elser tried to assassinate Hitler and his key lieutenants by detonating a bomb in the Bürgerbräukeller, a large beer hall in Munich that had been the site of the Hitler putsch sixteen years earlier, and the venue for annual commemorations attended by the Nazi party’s leadership.

Elser was a carpenter who sympathised with the Communist Party without following its orders, or anybody else’s, for that matter. He acted alone, although others may have suspected that he was up to something but kept quiet. Over a period of several weeks, he hid in the Bürgerbräukeller after closing time to install a bomb and a timer. The bomb went off exactly as planned, killing several people. But Hitler and other leading Nazis survived because fog had prompted the cancellation of Hitler’s return flight to Berlin. He spoke half an hour earlier than scheduled to be able to leave the event, together with his entourage, to catch a train back to the German capital. Most other attendees then also left.

Elser was twice unlucky: inclement weather saved Hitler, and then he himself was apprehended as he was trying to cross the border into Switzerland. When interrogated by the Gestapo, he confessed. He was never tried but kept imprisoned first in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp and then in Dachau, where the SS murdered him in April 1945.

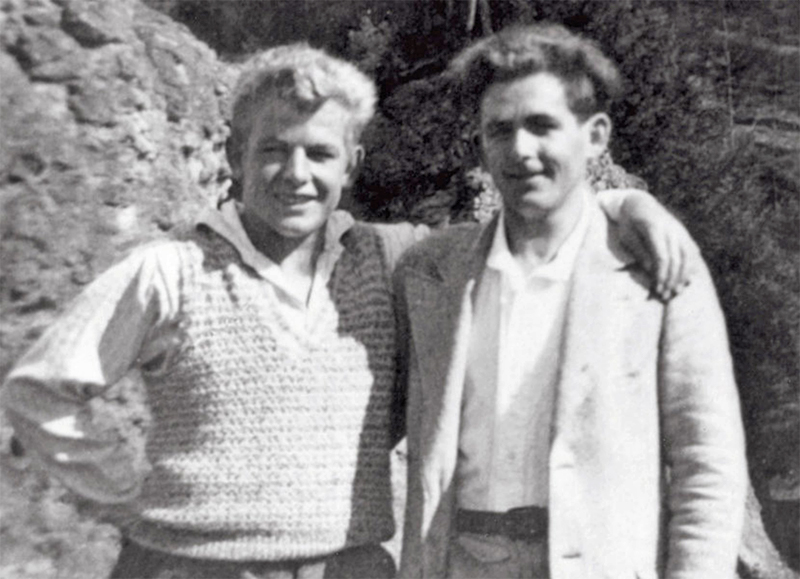

Neglected hero: Georg Elser (right) and his brother Leonhard around 1935. Private collection

Elser has not received the kind of attention enjoyed by the Scholls or Stauffenberg. The Allies suspected that he was used by the Nazis in the same way the Dutchman Marinus van der Lubbe was set up to be blamed for the German parliament building blaze in early 1933, which provided a pretext for the Nazis to get rid of their political opponents. The Nazis claimed that Elser had acted on behalf of British intelligence and Otto Strasser, a leading proponent of the Nazi party’s left faction who had quit the party in 1930 and by 1939 was living in exile in Switzerland.

After the war, German and British historians regurgitated the rumours about a Nazi conspiracy or a British secret service plot. In the absence of reliable historical sources they could do so unchallenged. Unlike Sophie Scholl, for example, Elser had not left any texts behind that could serve as evidence of his beliefs. It wasn’t until the transcripts of his interrogations by the Gestapo surfaced in 1964 that these rumours were proven baseless. The first biography of Elser appeared only in 1989.

Now Elser too is usually mentioned in the context of the German resistance against Hitler. He too has had streets named after him, at least one school carries his name, and in 2003 German Post issued a stamp to honour him. For some of his admirers, Elser, much more so than Sophie and Hans Scholl or Claus Graf Stauffenberg, is a true hero.

A few years ago, left-wing activist and historian Karl Heinz Roth concluded an essay about Elser by welcoming the fact that he had been rehabilitated and was now being recognised for his act of resistance. “Now we should take the next step and gently remove him from the pedestal where we put him,” Roth added. “For we should not let this kind of distance — the distance between us and the unreachable icon — become too wide.” Roth suggests that doing justice to Elser would involve situating him in the appropriate social, political and cultural contexts — which also means understanding his life against the background of the forces that shaped him.

Doing justice to Elser by taking his life history seriously is comparatively difficult because the most significant historical source was produced by the Gestapo agents who interrogated him. But the task is also comparatively easy because his life has not yet been completely overshadowed by the iconic figure on the pedestal.

That’s different in the case of Sophie Scholl. Apart from the transcripts of her interrogation, an abundance of written sources about her life — her letters, her diary and the testimonies of many of her contemporaries — allow the recently published biographies to highlight the complexity of her personality and her politics. They have shown that there was much more to her life than its last five days — and far more than what had been made public by her sister Inge. They have depicted her as a friend, daughter, sister and lover. They have shown her, for example, to have been an enthusiastic Hitler Youth leader, to have been deeply religious, to have a conflicted attitude towards her own sexuality, and to have been in love with another woman. They have demonstrated that her courage bordered on recklessness and that she was uncompromising in her beliefs. They also show that she was not a saintly victim.

Many of the magazine and newspaper articles marking her hundredth birthday promise to uncover the real Sophie Scholl, to show what is behind the image on the postage stamp. But the out-of-reach iconic image casts a shadow on her life that makes it difficult to see it for what it’s worth. To complicate matters further, there are two contradictory iconic images of Scholl. They are iconic not only in the metaphorical sense but also in the literal sense, because they are based on two sets of photographs.

In the first, she is depicted as a somewhat androgynous teenager — the hair cut short on one side, a quiff covering much of her face, wearing an expression suggesting an energetic, curious, stubborn, intense but also carefree person. In the second set of photos, which includes the famous shot taken by Jürgen Wittenstein in July 1942 that illustrates this essay, she has close to shoulder-length hair and appears as a committed young woman who wants to look proper and serious. While the latter’s dress, haircut and demeanour reveal her to be a historical figure, the former makes her look like a teenager of today: a Fridays for Future or Antifa activist, and queer feminist.

Over the years, the image of the young woman has been supplanted by that of the rebellious teenager, although the latter was not even contemplating any acts of resistance. Inge Scholl, who had first introduced the idea that her sister’s entire life foreshadowed its tragic ending, promoted the image of the earnest and morally rigorous young woman, which was also used for the stamps issued in the 1960s and 1990s, for her likeness at Madame Tussaud’s and for her bust in the Walhalla hall of fame.

Lena Scholze, who played Scholl in both Verhoeven’s The White Rose and Adlon’s Five Last Days, personified that historical figure. The 2021 stamp and the covers of all recent biographies depict her as a strong-willed and open-minded teenager who looks like she could be our contemporary, rather than the enthusiastic teenage member of the girls’ wing of the Hitler Youth.

Given the shadows cast by this heroic icon, attempts to convince women like Jana from Kassel that they have little in common with the “real” Sophie Scholl may be in vain. And AfD politicians who mine the leaflets distributed by her and her friends for tweetable phrases that purport to endorse right-wing populist politics are unlikely to be swayed by reading the latest Scholl biography.

But the issue is not that Jana and other confused pandemic protesters don’t know enough about Sophie Scholl. Rather, if they mistake the Merkel government for the murderous Nazi regime, they don’t seem to have a clue about the forces responsible for beheading Scholl — forces, incidentally, that were toppled by the armies of the Soviet Union and the Western Allies, and hardly troubled by a largely impotent German resistance. •