In the desire not to cause offence, multicultural Australia ties itself in terminological knots. When we talk of an ethnically diverse community we mean an ethnically specific one, with the term community postulating a warm cohesion that transcends all other attachments. We celebrate the contribution made by groups of migrants, happy for them to create ways of maintaining a distinctive culture as they find their place here.

Accounts of the multicultural experience typically relate how each ethnic group made its distinctive contribution to the Australian mosaic. The story begins with dislocation and the shock of arriving in a distant, unfamiliar setting, and recounts how the new arrivals settled in with the help of compatriots and maintained old customs to complement the new. Australia’s migrant history thus becomes an accumulation of journeys, from the First Nations to the most recent arrivals, in an affirmation of inclusiveness.

This celebratory story has some obvious problems. It overlooks the parallel process of exclusion, whether through the White Australia policy, or the system of permits and landing fees for non-British subjects, or the current regimen of incarcerating refugees. It sets aside the barriers — from overt discrimination and prejudice to blank indifference — faced by new entrants. And it oversimplifies the affinity of successive generations of settlers who share nationality but very little else.

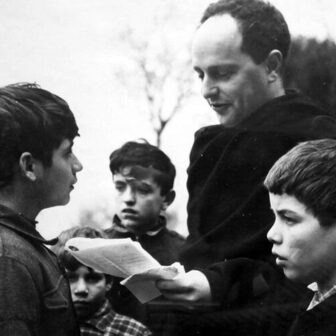

Take, for example, the young German men who came to Australia from the late 1940s to the early 1950s under a Special Projects scheme. It was similar to the much larger postwar program of resettling “displaced persons,” or DPs — for which these Germans were not eligible — and involved a two-year agreement to work as directed, which in practice meant manual labour in isolated settings. In South Australia the Lutheran Church made a special effort to minister to these Germans but found them disappointingly unresponsive. In contrast to the close-knit rural settlements of earlier German settlers, their experience was urban. Having spent their childhood in the Nazi youth movement and survived the trauma of war and defeat, they couldn’t share the piety of the pastors who ministered to them. There was a gulf that ethnicity could not bridge.

These reflections are stimulated by reading Sheila Fitzpatrick’s new book on the Russians who migrated to Australia after the second world war (reviewed for Inside Story by Phillip Deery). White Russians, Red Peril is subtitled A Cold War History of Migration to Australia and forms the capstone of a collaborative project she initiated some years after she returned to Australia from the United States. It involved her longstanding research partner, Mark Edele, and younger Sydney-based scholars. One of them, Jayne Persian, has already published Beautiful Balts, an accomplished history of the scheme that brought 170,000 DPs from camps in Europe to Australia from 1947 to 1952. Another, Ruth Balint, has researched the China Russians. Ebony Nilsson, one of Sheila’s postgraduate students, has examined a small subgroup, former Soviet citizens with left-wing views.

Strictly, Soviet citizens were not eligible for resettlement. Under an agreement struck in February 1945 as German resistance crumbled, the three principal Allies — Britain, the United States and the Soviet Union — agreed that all Soviet citizens liberated by American and British forces would be held in camps until they could be handed over to the Soviet authorities — just as British and American prisoners of war in areas liberated by the Red Army would be returned to their homelands. Millions of Soviet citizens were held in Germany, including some two million prisoners of war, five million forced labourers and a significant minority who had served in the Wehrmacht.

Not all of them were Russians, for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics incorporated other Slavic peoples, as well as Cossacks and Muslim ethnic groups. Along with these subjects of the old tsarist empire, the Soviet Union had acquired (or regained) others in the course of the war, notably in the Baltic states and Eastern Poland. For understandable reasons, many of these people had no desire to be repatriated; and the same was true of many Russians once Stalin made clear that even prisoners of war were traitors who would be punished.

In the immediate aftermath of victory the Allies forcibly sent these prisoners of war and forced labourers back to the Soviet Union, though the United States and Britain didn’t accept the Soviet claim for citizens of the Baltic states and, less consistently, West Ukrainians and West Belorussians. Then, as the cold war took hold, they resisted further Soviet claims, including for those who had served the German war effort and staffed the concentration camps. Russians frequently adopted another European nationality in the process. Furthermore, as the original United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration gave way to the US-controlled International Refugee Organization, the policy shifted from restoring these DPs to their European country of origin to resettlement outside Europe.

Australia was one of the principal participants in this DPs scheme. The arrangement allowed the government to select those who applied to come here, subject to an agreement that they would work as directed for two years. Jayne Persian provides the fullest and best-informed account of what this meant, but it needs to be emphasised that humanitarianism played little part in the decision to take such large numbers of continental Europeans. Put simply, Australia had a desperate shortage of labour and couldn’t wait for British migration to resume.

Perhaps Fitzpatrick’s most startling revelation is that Russians made up some 20,000 of the 170,000 DPs who chose Australia. They included so-called White Russians who had left Russia following the 1917 revolution and subsequent civil war. Strictly these were refugees rather than DPs, though the change of regimes in liberated Europe uprooted many of them, as the Chinese revolution of 1949 did Russians living in Harbin and Shanghai, 5000 of whom settled here in the 1950s.

Drawing on Russian as well as Australian archives, Fitzpatrick reveals the complex composition of these exiles in vivid detail. Among the 50,000 or so Russians living in Harbin in the 1920s and 1930s, for example, were White generals still working to restore the ancien régime, Russian Jews with bitter memories of how it had treated them, members of the Russian Orthodox Church, technicians working for the Manchurian continuation of the Trans-Siberian Railway, fascists who collaborated with the Japanese occupation and patriots who followed the fortunes of the Red Army.

Russians were largely invisible in Australia’s postwar migration story. That was partly because they concealed their nationality as a condition of entry and partly to avoid the attention of Australian and Soviet security agencies. Working from the Soviet embassy, security officers sought to persuade their compatriots to return, with minimal success. From the outset the Australian government sought to screen out potential Russian spies and play down the presence of war criminals. Yet even on the voyage to Australia, the newcomers accused each other of communist and Nazi allegiance.

Anti-communism was the dominant creed, though Fitzpatrick notes that Russians lost out in the cold war contest for attention to other national groups who had the additional advantage that they could claim to represent “captive nations.” Her book is also a reminder that ethnic identities never encompass all migrants with a common nationality. As the Russian example makes clear, such identities are embedded in history and subject to politics. •