A Journey: My Political Life

By Tony Blair | Hutchinson | $35

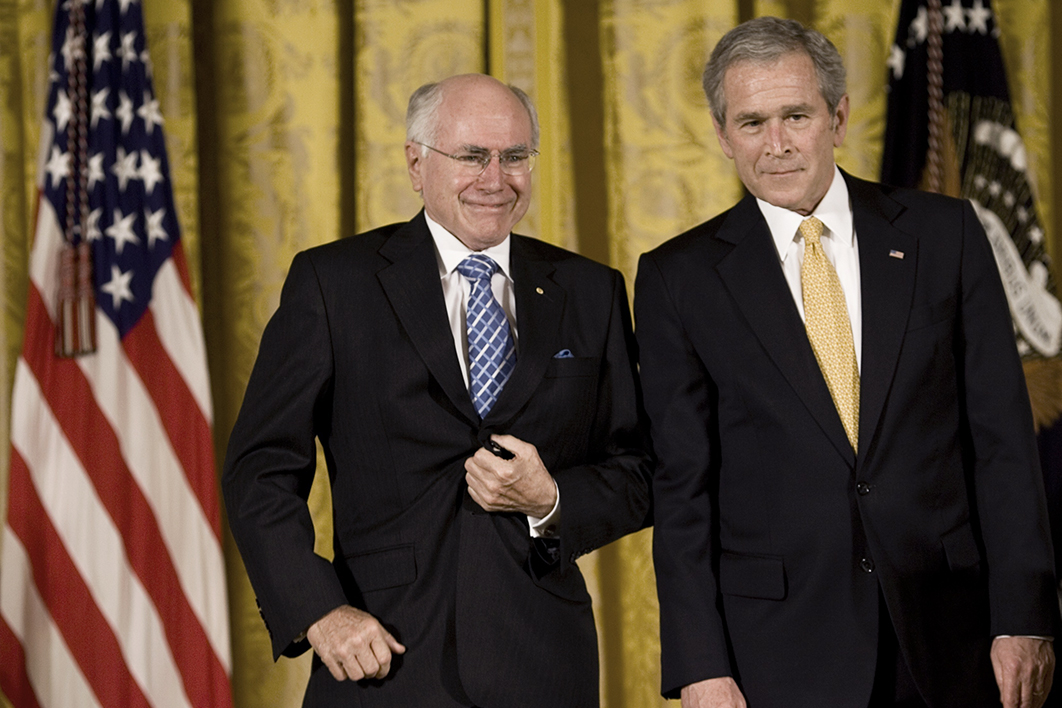

Lazarus Rising

By John Howard | Harper Collins | $59.99

Decision Points

By George W. Bush | Crown | $49

The recently published memoirs of George W. Bush, Tony Blair and John Howard are a reminder that in the lead-up to the 2003 Iraq war all three pointed to the threat of Iraqi weapons of mass destruction as the major reason for the invasion. We now know that there were no WMDs, but in an interview in December 2009 former Prime Minister Blair said he would have thought it right to remove Saddam Hussein even if he had known that this was the case. He would have had to “deploy different arguments,” he told the BBC.

Mr Blair’s comment prompts some questions. Were the leaders of the United States, Britain and Australia mainly and genuinely motivated by the weapons issue or was it chosen for “deployment” because it was thought easiest to sell to the public? Were they convinced that the existence of prohibited WMDs in Iraq would give them the right to go to war, if that was needed? Did they remain convinced that the weapons were there when, in March 2003, they launched the large and lethal armed intervention and became responsible for its impact? And, lastly, were their erroneous beliefs about the WMDs reasonable and excusable at the different points in time?

In September 2002, when the United States and Britain released their dossiers on Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction, Saddam Hussein’s failure to cooperate with UN weapons inspections during the 1990s was still fresh in people’s minds. Many people no doubt thought, not unreasonably, that Iraq had behaved in this way to avoid disclosing hidden weaponry. At least some governments thought so too. In Lazarus Rising, Mr Howard talks about a “reasonably entertained belief that Iraq possessed WMDs.” In Decision Points, Mr Bush writes that “virtually every major intelligence agency in the world had reached the same conclusion: Saddam had WMDs in his arsenal and the capacity to produce more…,” and these conclusions were presented in great detail in the dossiers. In his preface to the British dossier, Mr Blair assured readers that he “was satisfied as to its authority” and that the threat posed by Iraqi WMDs was “serious and current.”

But the evidence behind these conclusions was nowhere to be found. For the team of UN weapons inspectors that I headed, the findings were plausible, but we needed evidence.

Weapons inspectors working for UNSCOM, the first UN inspection authority for Iraq, had left the country late in 1998 after the Iraqi government withdrew its cooperation. Soon after, UNSCOM presented a report listing a large number of WMD items that might or might not have still existed, but weren’t accounted for. Since then, governments had received information from aerial surveillance and, we may assume, from intelligence sources. How much had they learnt from these sources by September 2002? A lot, according to the dossiers released to convince the world about the existence of substantial stocks of WMDs. Not much, judging by Mr Bush’s account in Decision Points. Once the inspectors had left in 1998, he writes, “the world was blind” to whether Saddam had restarted his programs. Yet by 2002 the question marks in the inspectors’ 1999 report had been replaced by the exclamation marks of the government-sponsored dossiers.

UNMOVIC, the new UN inspections authority, began work on 27 November 2002, and by Christmas we had carried out quite a number of inspections. At around this time, Mr Bush was briefed by the deputy head of the CIA, John McLaughlin – not on the results of UN inspections but on US intelligence that could be declassified to explain Iraq’s WMD program to the public. Mr Bush writes that he was not impressed and commented, “Surely we can do a better job of explaining the evidence against Saddam.” In Decision Points, to his credit, he comments that, “in retrospect, of course, we all should have pushed harder on the intelligence and revisited our assumption.” They should indeed.

Surely the governments demanding that Iraq accept renewed inspections would have eagerly absorbed and seriously considered all the information that started to flow when the inspectors returned to Iraq after four years of absence? I doubt they did, at least at the political level. While the inspectors carried out ever more professional searches, suspicious but not assuming that there were WMDs, the United States and its friends had already staked out their firm conclusion that Iraq retained the weapons. What they wanted was either that the inspections should discover WMDs or – more likely – that Iraq would obstruct or reject inspections, thereby providing a ground for military action, with or without the authorisation of the Security Council. In both respects they were disappointed.

The three leaders’ memoirs reflect various reactions to the results of the inspections. Not surprisingly, all of them cite inspectors’ comments that were critical of Iraq, especially some that I made in the report to the Security Council on 27 January 2003. Mr Bush notes that inspectors had discovered warheads, and that Iraq was defying the inspection process, blocking U2 flights. Like Mr Blair and Mr Howard, he quotes me – correctly – as saying that Iraq “appears not to have come to a genuine acceptance, even today, of the disarmament that was demanded of it.”

What the authors fail to say – and perhaps did not want to notice at the time – was that Iraq’s expected (and probably hoped for) obstruction had largely not materialised. Mr Howard compounds this oversight when he writes that “once again the old cat and mouse game was played by the Iraqis.” Rather, there seemed to be a prospect of an unimpeded inspection process – at least if the military pressure remained. I noted that Iraq “has on the whole cooperated rather well so far” on process and that “access has been provided to all sites we have wanted to inspect and with one exception it has been prompt.” The criticism I voiced was in relation to Iraq’s failure to be “proactive”: either it should surrender WMDs, if there were any, or help to dispel the many unresolved issues. My comments were deliberately sharp, because I wanted to push Iraq hard to cooperate actively, as Security Council resolutions demanded. On point after point I explained what Iraq could do.

Whether it was because of the visible military build-up or our warnings that if Iraq was not more helpful our reports would remain critical, or a combination of these factors, the Iraqis were becoming much more active during February. We reported this shift in attitude to the Security Council and to the US, British and Australian governments. On 11 February 2003, for example, directly after my return from a visit to Baghdad, I saw Mr Howard at his hotel in New York. In his memoirs he reports that I told him that the presentation of the American case to the UN Security Council by the secretary of state, Colin Powell, had been powerful but that some of his claims were “quite shaky” and US intelligence had not revealed a “smoking gun.” He comments that “the United States itself had not made that claim.” He cites me further as saying “that the United States and Britain were basing their political decisions on intelligence that, insofar as it had been shared with UNMOVIC, had not revealed much.”

Mr Howard might not have attached any importance to what I said. Like his American and British colleagues, he was apparently relying more on national intelligence agencies, ignoring the fact that UN inspectors reported on the basis of hundreds of inspections on the ground while much national intelligence came from defectors. Mr Howard writes: “The Australian intelligence authority consistently assessed that Iraq probably” – my italics – “retained a WMD capability… even if that capability had been degraded over time…” Rod Barton, a former Australian director of intelligence on WMDs, has been more specific. He reports that in December 2002 the Defence Intelligence Organisation advised the Howard government that “there has been no… known biological weapons production since 1991 and no known biological weapons testing or evaluation since 1991…” The DIO had assessed that although there might have been some old pre-1991 biological and chemical stocks, given the passage of time these weapons were of doubtful utility.

From my meeting with Mr Howard I went to see the US National Security Advisor, Condoleezza Rice. I told her that we had detected a more serious effort by Iraq to cooperate but could not exclude the possibility that it was part of a dilatory tactic. As I noted in my own book, Disarming Iraq, “I went on to say that I had not been ‘terribly impressed’ by the intelligence that had been provided by member states so far. By now UNMOVIC had been to a number of the sites indicated by intelligence tips and only one had proved of relevance to the commission’s mandate…”

In a telephone conversation with Mr Blair about a week later, on 20 February, I expressed even more scepticism about national intelligence. Summarising the conversation in my own book, I wrote that “while I appreciated the intelligence we received, I had to note that it had not been all that compelling. Only at three sites to which we had gone on the basis of intelligence had there been any result at all.” I told Mr Blair that “I tended to think that Iraq still had concealed weapons of mass destruction, but I needed evidence. Perhaps there were not many such weapons in Iraq after all… I added that it would prove paradoxical and absurd if 250,000 troops were to invade Iraq and find very little. Blair responded that the intelligence was clear that Saddam had reconstituted his weapons of mass destruction program. Blair clearly relied on the intelligence and was convinced, while my faith in intelligence had been shaken.”

Unlike Mr Howard, Mr Blair does not recount in his memoirs the doubts that had been conveyed from the inspectors. Rather, he writes that “there were those in the international intelligence community who disputed the extent of the programme, but no one seriously disputed that it existed…” And yet, at the very time when war preparations were accelerating and the three leaders would have dearly liked to hear that Iraq was obstructing inspections or that WMDs had been found, the inspectors were reporting cautiously but positively that inspection work – as I told the Security Council on 7 March – “is moving on and may yield results.” I can understand the discomfort this caused. But was it beyond Mr Blair – and some others – to understand that the better cooperation of the Iraqis, along with the results of inspections, were the reasons our tone shifted from a rather harsh and critical one in January to a more hopeful one toward the end of February and beginning of March? To be sure, the tone remained guarded. There was still a whole dossier of “unresolved disarmament issues” and there was the issue of a quantity of missing anthrax, the existence of which I had said, in January, was strongly indicated. (After the war it transpired that it had, in fact, been disposed of in the vicinity of one of Saddam’s palaces – a fact that no one dared to reveal while Saddam was still in control.)

Did the British, US and Australian governments not notice that significant parts of their evidence had collapsed? The International Atomic Energy Agency had shown that an alleged contract between Iraq and Niger to import uranium oxide was a forgery and had concluded that a number of aluminium tubes were not for centrifuges but for rockets. Did the governments not register that we had carried out over 700 inspections without finding any WMDs and that no such weapons were found at inspections of dozens of sites that their intelligence had pointed us to?

Did these three leaders believe that there were WMDs in Iraq when they invaded the country mid March 2003? I don’t see evidence of bad faith, but the points made above suggest that a minimum of critical thinking should have made them sceptical and led them to wait for firmer evidence before they embarked on the horror of war.

In Decision Points, Mr Bush says that after 9/11 he felt that he could not risk allowing Saddam to pass his WMDs to terrorists and that his “first choice was to use diplomacy.” A military build-up and a threat of action would show Saddam that his defiance was unacceptable and might convince him that the way to keep power was to give up his weapons. The maximum leverage would come “as the military option grew more visible.” This sounds logical and seems to confirm that Mr Bush believed the WMDs were there, but it is paradoxical that the leverage was discounted when it was reaching its maximum level and Iraq was showing more cooperation. It is true – as Mr Blair told the Chilcot Inquiry into the war on 29 January 2010 – that inspections would not have been able to prove there were no weapons, but they had become increasingly telling, not least in contradicting the faulty evidence on which the United States and Britain based their accusations.

I think the evidence shows that the war leaders must have gradually become aware – as the leaders of many other governments did – that the evidence of WMDs was shaky. Other motivations must have helped to drive the armed action forward.

The risk that Saddam Hussein might reconstitute a WMD program

The foremost of the motivations that emerged after it became clear there were no WMDs was the alleged need to prevent Saddam Hussein from reviving his weapons program.

In Lazarus Rising, Mr Howard notes that Australian intelligence assessed “that Iraq maintained both an intent and capability to recommence a wider WMD program should circumstances permit it to do so…” This meant that “leaving him be was too great a risk for the United States to take.” Mr Blair, referring to interviews conducted by Charles Duelfer’s Iraq Survey Group after the war, writes, “The danger, had we backed off in 2003, is very clear; the UN inspectors led by Blix were never going to get those interviews; they may have concluded (wrongly) that Saddam had given up his WMD ambitions; sanctions would have been dropped; and it would have been impossibly hard to reapply pressure…”

There are three comments that can be made about this post-conflict rationale. First, had the authors come to their parliaments early in March 2003 and said, “We aren’t certain about the existence of WMDs but we shouldn’t take the risk that Saddam could revive his program if sanctions are lifted in the future,” there would have been no authorisation of war. The decision presented to legislatures and to the public was based unequivocally on the existence of the weapons at the time.

Second, the three leaders are eagerly seizing straws kindly handed to them by the Iraq Survey Group, the mission sent after the invasion of Iraq to find the WMDs. On a closer look, the straws prove flimsy. Both David Kay, the first leader of the Iraq Survey Group, and Charles Duelfer, his successor, were competent inspectors but they were also strong proponents of the war and had been appointed by the head of the CIA. Although David Kay acquired fame by declaring that there were no WMDs, he reported that his team had “discovered dozens of WMD-related program activities and significant amounts of equipment that Iraq concealed…” Mr Howard cites this statement but doesn’t mention that it was brushed aside by Duelfer. In a passage not cited by the memoir authors, Duelfer describes how loose the basis was for asserting that Saddam was a future threat: “The former regime had no formal written strategy or plan for the revival of WMDs after sanctions. Neither was there an identifiable group of WMD policy makers or planners separate from Saddam. Instead, his lieutenants understood WMD revival was his goal from their long association with Saddam and his infrequent, but firm verbal comments and directions to them.”

Third, we must remember that if the invasion had not been launched then the sanctions and the “reinforced system of ongoing monitoring and inspections” would have continued under Security Council resolution 1248. That monitoring system would have remained in operation even had the Council at some stage been satisfied with Iraqi compliance and decided to suspend the sanctions – as it could for renewable periods of 120 days. Of course, we cannot know how the Council would have handled Iraq over a longer period. What we do know is that if the invasion had not been launched in March 2003 inspections and monitoring would have continued and a strong built-in alarm and sanction mechanism would have remained in place.

In March 2003 Iraq was exhausted after two wars and over a decade of sanctions. It cannot have been seen as a military threat. It is also hard to believe that concern about continued or revived WMD programs could have sufficed to convince the authors of the memoirs about the need to go to war. What other motivations can be discerned from the writings of the warlords?

Did the protection of a continued flow of oil play a role?

Although Mr Bush explicitly denied that oil was a motive, the American interest in ensuring uninterrupted oil deliveries from the Middle East may well have played a role. In a famous interview in Vanity Fair in June 2003, Bush’s deputy secretary of defense, Paul Wolfowitz, said that the potential to remove US troops from Saudi Arabia was an unnoticed but “huge” factor. Presumably the troops had been kept there to protect the country and its oil exports against a possible threat from Saddam – despite the provocation that the presence of US troops on holy soil was deemed to provide to al Qaeda. The prospect of Iraq freed from Saddam, Iraqi territory in hands friendly to the United States and the threat to Saudi Arabia and the Gulf removed must have been appealing. A potential military springboard would also be created from which the United States could, if need be, handle another possible threat to the oil flows, Iran.

Or solidarity among allies?

The United States expected the NATO countries to work together, and this was indeed a factor that motivated many – but not all – members of the alliance to support Washington’s plans for action in Iraq. Mr Bush records frustration and disappointment over the Turkish parliament’s vote against permission for US troops to enter Iraq from Turkish territory. “On one of the most important requests we had ever made, Turkey, our NATO ally, had let America down,” he writes.

Although it is not a NATO member, Australia, on the other hand, was a most loyal ally. Mr Howard writes that while the weight of Australian public opinion was against the decision to go into Iraq he and his colleagues carefully argued the case that Saddam had WMDs, adding: “Never far beneath the surface was, however, the alliance dimension of the decision.” In a speech he quotes in his book he explained: “There’s also another reason and that is our close security alliance with the United States. The Americans have helped us in the past and the United States is very important to Australia’s long term security…” In another passage, he talks about basing his decision to go to into Iraq, “partly, at least, on the strength of our decades-old and crucially important American alliance.” He pours indignation on Mexico’s president, Vicente Fox, who did not support the United States. “Fox was invited to address a joint sitting of congress, within months of taking office. Iraq was an example of such gestures not being reciprocated…” What lack of gratitude!

Doing away with an evil dictator

How important was the freedom agenda as a motivation for the war? Because Mr Howard makes no reference to it in his book, we might perhaps conclude that the nature of the Iraqi regime did not weigh heavily in his determination to join the intervention. With the US and British leaders it was different. Mr Bush writes that he and Tony Blair were “kindred spirits in our faith in the transformative power of liberty.” There is no reason to doubt the sincerity of this feeling and his belief that a democratic Iraq would be safer for the world than a tyrannical one. Mr Bush also reports that Elie Wiesel had advised him that he had a moral obligation to “act against evil.” Nevertheless, it is hard to know how heavily the tyrannical nature of Saddam’s regime weighed as reason for the United States to go to war. In his Vanity Fair interview Mr Wolfowitz said that the criminal nature of the regime could hardly be a reason to “put the lives of American kids at risk.”

Mr Blair describes how deeply engaged he was in the question of international intervention against tyranny and how it motivated him in the case of Iraq. In a speech in Chicago on 24 April 1999, during the Kosovo conflict, Mr Blair had set out a Doctrine of the International Community, which contained a very simple notion: “intervention to bring down a despotic dictatorial regime could be justified on grounds of the nature of that regime, not merely its immediate threat to our interests…”Although he writes that he was careful to hedge the doctrine with limitations, he poses the question: where these do not apply, where intervention is “practical” and where change will not come by evolution “should those who have the military power to intervene contemplate doing so?”

Mr Blair remained fascinated by that question – rightly so, in my view. It appealed to the crusading spirit in him. He notes with enthusiasm that in his State of the Union address in January 2002 Mr Bush had talked about the “axis of evil.” For Mr Blair, this indicated that the United States “was set on changing the world … if necessary by force…” He (Blair) had reached the same conclusion in relation to the Middle East, to which he believed “we would bring democracy and freedom…” He goes on: “In my first term, we had toppled Milosevic and changed the face of the Balkans. In Sierra Leone, we had saved and then secured democracy.” By April 2002 Mr Blair had resolved in his own mind that “removing Saddam would do the world, and most particularly the Iraqi people, a service,” and he writes that when he addressed the House of Commons on 18 March 2003 “the moral case for action – never absent from my psyche – provided the final part of my speech and its peroration, echoing perhaps subconsciously the Chicago speech of 1999.”

Mr Blair notes briefly, however, that while he was fascinated by the question of intervention against oppression “it did not cut much ice with the British public.” Nor, as we shall see, was it easy to apply within the confines of the rules set out in the UN Charter and the principles of British foreign policy.

IT IS striking that none of the three leaders of the Iraq war seems to have cared much about the UN Charter restrictions on the use of force. Rather, they saw them as obstacles to be ignored or circumvented.

In April 1999 Mr Blair might have thought that interventions against despotic dictatorial regimes could legitimately be taken without Security Council authorisation. If he did, he certainly received different advice later on. In testimony to the Chilcot Inquiry last year, Lord Goldsmith, the attorney-general in Mr Blair’s government, said that during the year before the invasion he did not see any evidence of an “imminent threat” to Britain that would justify war and that during a meeting with Mr Blair in July 2002 he had stressed that a new UN resolution would be necessary to authorise military action. He also said that he did not think that this advice was “welcome.” Jack Straw, the British foreign secretary during that period, told the Chilcot Inquiry that he had advised that the US policy of “regime change” could never be part of British policy. Mr Blair must have received all this unwelcome advice very reluctantly. He writes that “though I knew that regime change could not be our policy, I viewed a change with enthusiasm, not dismay.” He came to “a firm conclusion that we could only do it [remove Saddam] on the basis of non-compliance with UN resolutions.” As noted by Lord Goldsmith, Mr Blair went on to convince Mr Bush to try “for UN approval for action against Saddam.”

The US National Security Strategy that the Bush administration published in September 2002 completely ignored UN Charter restrictions and gave the green light to armed interventions against any threat deemed serious enough. Mr Bush writes that his vice-president, Dick Cheney, and defense secretary, Donald Rumsfeld, took the view that a UN resolution authorising an intervention was unnecessary from a legal standpoint and that he himself did “not have a lot of faith in the UN.” Nevertheless, he went along with the idea advanced by Mr Blair and many friendly governments to seek a Security Council resolution that demanded Iraq accept UN inspections and disarm. This was Resolution 1441, adopted on 8 November 2002, which called on Iraq to “cooperate immediately, unconditionally, and actively with UNMOVIC and the IAEA.” It did not contain any clause explicitly authorising armed action in case of non-compliance but stipulated for such cases that the Council should meet and “consider the situation and the need for full compliance… in order to secure international peace and security.”

In January 2003 Mr Bush and Mr Blair agreed that Iraq had violated the new resolution and that there were ample reasons to take enforcement action. Nevertheless, Mr Blair wanted a second resolution authorising armed action. Although Mr Bush did not want to “plunge back into the UN,” and his top team (including Powell) was opposed to it, he was aware that Mr Blair was facing intense internal pressure on the issue of Iraq and agreed on the tabling of a new resolution.

Against the background of Australia’s longstanding reputation as one of the pillars of the United Nations, Mr Howard comes out sounding remarkably disdainful of both the Charter and the organisation itself. While the Charter affirms the right of individual or collective self-defence if an armed attack occurs, in effect he accepts – like the Bush administration in its National Security Strategy of 2002 – the concept of preventive war. He writes that going into Iraq was right, among other reasons, as “a legitimate act of anticipatory self defence.” He thus endorses a concept that puts the label of self-defence on any armed action claimed by its author to be a response to a threat, present or future.

Mr Howard seems to have felt sheer disdain for British squeamishness about the United Nations. “Tony Blair led the British Labour government which included many with an almost childlike faith in the processes of the United Nations,” he writes. “To them the sine qua non of good foreign policy was always adhering to the dictates of multilateral organisations, especially the United Nations…” Although Mr Howard, along with Mr Blair and several other allies, wanted a second resolution authorising the armed action, they chose to declare it legally unnecessary when they saw that American action was inevitable and a resolution unattainable.

Indeed, by the time he wrote Lazarus Rising Mr Howard had abandoned his support for the resolution with a vengeance. He pours scorn on the Australian Labor Party for being ready to support Australian involvement in an armed action provided the resolution was adopted – the same resolution that he and Mr Blair had sought and that Mr Blair had desperately tried but failed to get. In Mr Howard’s view Labor was making its stand contingent on how Russia and France voted in the Security Council. Labor was happy, he writes, to “outsource Australia’s foreign policy on Iraq to the Russians and the French, both of whom agreed Iraq had WMDs but were determined to exploit their power of veto in the Security Council for political advantage.”

Leaving aside the fact that the French president, Jacques Chirac, didn’t think that Iraq had WMDs and that Russia had expressed doubts throughout 2002 and into 2003, several points need to be made here.

Would Mr Howard not recognise that there is an important difference between an Act appropriately passed by majority in a parliament and a proposal that failed – even narrowly – to attain a necessary majority? In the UN Security Council, as in parliaments, there is a difference between proposals that carry and those that – for want of majority support – don’t. Proposals require acceptance by all five permanent members and also by a majority of the fifteen members. In February and March 2003 it was not only French and Russian resistance – and their possible vetoes – that led the sponsors of a resolution implying permission to take military action against Iraq to refrain from pursuing such a proposal; there was no overall majority for such a proposal among Council members. And had a proposal of this kind come before the General Assembly it would have been defeated by a crushing majority. Was it so shocking that the Labor Party made its support for Australian participation in the war dependent on a valid resolution?

At the end of his chapter about Iraq Mr Howard comes back to the absence of a supporting Security Council resolution and writes: “To baulk at that decision [to stand beside the Americans], purely on the basis that the Security Council had not passed another resolution – especially when it had not been deemed necessary in 1998, when similar action was contemplated [the US/UK punitive bombing of Iraq] seemed to me to be cloaking unwillingness to confront the substance of the issue with a thin and legalistic veneer.” Are we to draw the conclusion that in 2003 – when the United States had become the only superpower in the world and the Russian veto power in the Security Council was no longer underpinned by a military power matching that of the United States – the rule of unanimity had, in Mr Howard’s view, become a “thin and legalistic veneer”?

Under the Bush administration’s National Security Strategy, all that was required to justify armed intervention was for the United States to identify a threat to its national security. “The greater the threat,” according to the doctrine, “the greater the risk of inaction – and the more compelling the case for taking anticipatory action to defend ourselves, even if uncertainty remains as to the time and place of the enemy’s attack.” This position was confirmed very publicly during the 2004 presidential campaign. When Senator Kerry suggested that the initiation of armed actions against other states would have to stand up against what he called a “global test” the responses from President Bush and others left no doubt that the administration felt that using any external yardstick to assess pre-emptive armed actions was ridiculous, as was any idea of asking the Security Council for a “permission slip.”

According to Mr Howard, the legal advice given to his government was that there was sufficient authority under earlier UN resolutions to justify the armed action. There is a contradiction here: if the action were a “legitimate act of anticipatory self-defence,” as he also claims, then he could have defended it without reference to UN resolutions. It is puzzling that while Mr Howard considered that the “principle at stake” was “the failure of Iraq to fully comply with the United Nations requirements regarding WMDs” he was furious about the Labor Party’s relying on a decision by the Security Council. It would have been more consistent if he had said that Iraq did not care about UN resolutions and he himself did not care about the Charter rules.

Alone among the three leaders, Mr Blair was obliged to wrestle with the restrictions on the use of armed force stipulated in the UN Charter. He had understood that use of force simply to bring about “regime change” could not be British policy and that the action could only be taken “on the basis of non-compliance with UN resolutions.” But while British government officials like Lord Goldsmith and Jack Straw – not to mention the civil service and the public – believed that the UN restrictions are an essential feature of modern international relations, for Mr Blair they seem to have looked rather like obstacles that had to be circumnavigated to get to action that he thought was morally right. He writes that he “understood the importance of a second resolution in terms of political survival and so forth,” but that he “always thought it a bit odd in terms of the moral acceptability of the course of action.” In other words, the moral acceptability mattered to him while the Security Council authorisation was of importance only indirectly because it mattered to a public opinion that could topple him. He did not ponder the possibility that in resisting authorising the use of armed force precipitously it was the majority of the Security Council that showed wisdom.

Mr Blair suggests that the judgement of history will be on the side of intervention against oppressive regimes. He feels encouraged by the fact that in 2005 a UN summit adopted the Responsibility to Protect: the principle that the international community has a duty to intervene if a government fails in its responsibility to protect its citizens against mass atrocities. But in proclaiming that doctrine the summit did not endorse any modifications in the UN Charter rules regarding the use of armed force. The major UN report, A More Secure World, prepared by the UN Secretary-General’s High-Level Panel on Threats, Challenges and Change, was also clearly opposed to any idea Mr Blair might have had that “those who have the military power to intervene” can do so without an authorisation by the Security Council.

In testimony before the Chilcot Inquiry in January this year, Lord Williams of Baglan, an adviser to the British foreign secretary between 2001 and 2005, concluded: “A cardinal lesson for the future must be that the UK should never again go to war except on the basis of self-defence, compelling humanitarian emergency or authorisation of the UN Security Council. The Iraq experience has shown that without this the prosecution of war in our age is deeply divisive domestically and internationally.” Lord Baglan probably wanted to give room for actions like the Kosovo bombing, but the UN Secretary-General’s High-Level Panel was more restrained. Discussing the threat of the acquisition of nuclear weapon–making capability by a state with allegedly hostile intent, the panel’s report states that if the threat is imminent, a well-established rule allows a threatened state to take armed action in self-defence. For cases where the threat is not imminent, the panel rejects any right of “anticipatory self-defence,” stating that there is “by definition” time to put the matter to the Security Council, where different strategies can be considered.

The Panel provides a succinct rationale for this restrictive line – a rationale that the successors of George Bush, Tony Blair and John Howard should bear in mind if they begin to consider military action of this kind: “[I]n a world full of perceived potential threats, the risk to the global order and the norm of non-intervention on which it continues to be based is simply too great for the legality of unilateral preventive action, as distinct from collectively endorsed action, to be accepted. Allowing one to act so is to allow all.” •