The headline advice I received twenty-five years ago was “Don’t do it!” I had just graduated from Macquarie University with an honours degree in modern history along with — as one thesis examiner joshed — “endless enthusiasm.” My passion for history was increasingly focused on the media.

I had been introduced to primary sources in a second-year Australian history course by Frank Clarke, who had encouraged me to read “old newspapers.” This was the analogue era, well before Trove and digitised newspapers, and so I went in search of political cartoons using the microfilms in the bowels of the old Macquarie University Library. I spent a good deal more time there in my 1992 honours year, as well as in the newspaper section of the State Library of New South Wales, researching how the press had portrayed former Labor leader Dr H.V. Evatt.

During my honours year I had encountered Company of Heralds, Gavin Souter’s superb 1981 history of the Fairfax media corporation, which he followed up a decade later with Company of Heralds: The House of Fairfax 1841–1992. I was struck by the fact that there was no equivalent history of the other big Sydney publisher, Australian Consolidated Press, and the only biography of its founder, Frank Packer (1906–74), was a hagiography written while he was still alive.

And so my honours and PhD supervisor, Duncan Waterson, suggested that I talk to a retired colleague, then the finest historian of the New South Wales press, about my interest in writing a biography of Sir Frank or a history of ACP. The telephone conversation was dispiriting — with the best of intentions, the historian expressed concern that there was no ACP archive (as there was for Fairfax) and no known Packer family papers. The fearsome reputation of the intensely private Kerry Packer (Sir Frank’s son and heir, and the richest person in Australia at the time) may also have been mentioned.

By early 1993, following a polite “no” from Kerry Packer’s office, I was increasingly concerned about how I would research aspects of his father’s private life. But Sir Frank’s public career, and his business, still seemed to have potential. At the very least, I could probe ACP’s own magazines and newspapers — led by the Australian Women’s Weekly, the Daily and Sunday Telegraphs, and the Bulletin.

As I began wading through oceans of microfilm, I convinced myself that a company history would be possible, with additional material available in the form of journalists’ and editors’ manuscript collections (some of them in the State Library of New South Wales); the records of journalist and printers’ unions (principally in the Noel Butlin Archives Centre in Canberra); regulatory material, ranging from the Department of Information to the Australian Broadcasting Control Board (in the National Archives of Australia); and oral history interviews.

By mid 1993, having mined Gavin Souter’s first volume and talked to him about my project, it was clear to me that relevant material was held in the Fairfax archive. It was hard to know how much, given I was in the early stages of working on the history of a rival company. But for me (and, I dare say, Gavin), the stories of the knights of the Sydney press — the Fairfaxes and the Packers — have always been imbricated and inseparable.

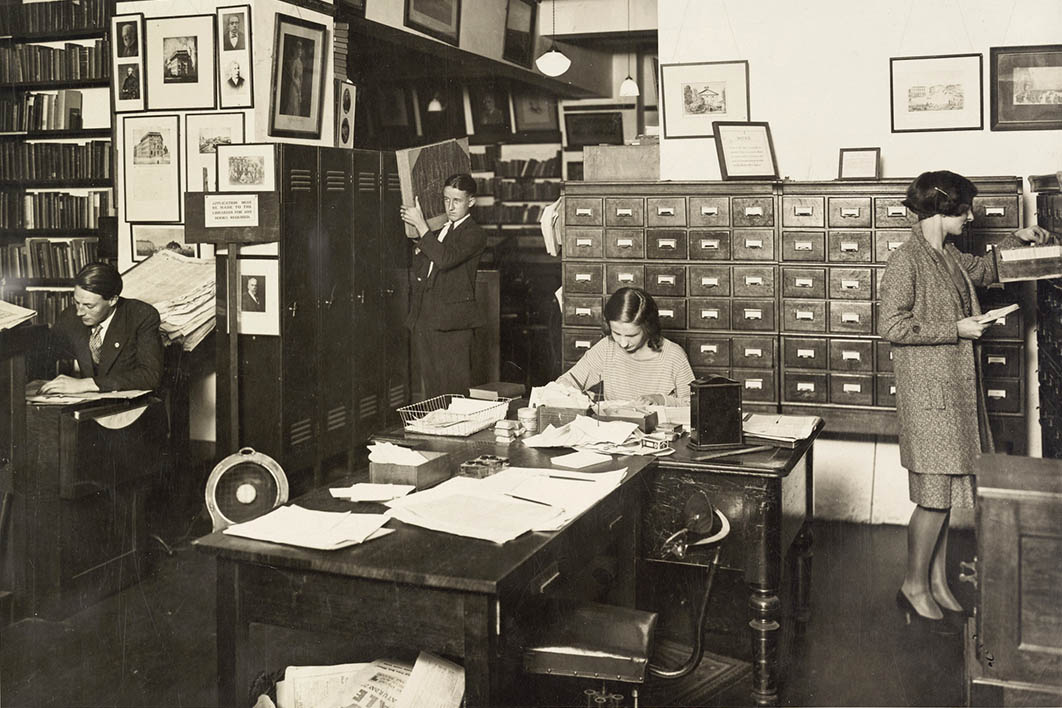

In July 1993 I wrote my first letter to Fairfax’s chief legal counsel and company secretary, Gail Hambly, requesting access to the collection. Within weeks, I was walking from Central Station to Mountain Street, Ultimo, where the archive was housed, not far from Fairfax headquarters in Jones Street. The company’s first archivist, Eileen Dwyer, had recently retired, leaving her successor, Louise Preston, to continue attempting to compile detailed listings of the collection’s 1400 boxes. I occupied one of the two desks in the archive, making notes in pencil, while Louise occupied the other.

It became increasingly clear that the archive would be pivotal to my PhD thesis. Last weekend I retrieved from my own archive the folders of pencilled notes I took as I researched first a company history and then a biography of Sir Frank. In the book based on my thesis, The House of Packer: The Making of a Media Empire (1999), I acknowledged the debt I owed to the Fairfax archive. Some of the material I found there also helped to flesh out the biography of Sir Frank. The NSW working party of the Australian Dictionary of Biography had decided to take a punt on a young historian by inviting me to write the major Packer entry, and this undertaking, leading as it did to research on ancestry, schooling, sport, marriages and children, helped to convince me that a full-scale biography, encompassing the personal as well as the public, was viable. Both were published in 2000.

Dipping into my folders, I thought I might pull out some examples of the sorts of Fairfax material that helped to inform my Packer books. It’s important to note that the archive contains the records of many companies and outlets acquired by Fairfax.

Of particular value to me were the records of Associated Newspapers Ltd, which Peter Arfanis from the State Library of New South Wales wrote about in a blog about the Fairfax archive late last year. This corporate octopus was created by Sir Hugh Denison in 1929, when he merged the Sun, the Sunday Sun, the Daily Telegraph Pictorial, the Sunday Pictorial, the Newcastle Sun, World’s News and Wireless Weekly with the holdings of S. Bennett Ltd — the Evening News, the Sunday News, Woman’s Budget and Sporting and Dramatic News.

The Sydney Morning Herald building on the corner of Pitt and Hunter streets, c 1920s. Fairfax Media Business Archive, State Library of New South Wales

Through the chairman’s correspondence, the board’s minute books, and legal agreements — all held in the archive — we can trace the machinations behind the chain’s purchase of the Daily and Sunday Guardians in 1930; the slide in the share price as the company published titles that competed with each other during the Great Depression; and the closure and mergers of several titles.

I found concrete evidence of Robert Clyde Packer’s attempt to protect his shareholding by moving from Smith’s Newspapers to become managing editor of Associated Newspapers’ remaining papers, and his fight against NSW premier Jack Lang’s legislation designed to bankrupt Packer and his son, Frank. The archive contains rich details of Packer senior’s authorising of Associated Newspapers to pay Packer junior and E.G. Theodore £86,500 not to publish an afternoon newspaper for three years. This extraordinary 1932 deal seeded the creation of the Australian Women’s Weekly, and the formation of the Packer media empire.

Minutes of staff conferences from mid 1933 onwards show John Fairfax and Sons, as well as Associated Newspapers, monitoring the circulation and interstate launches of the Women’s Weekly, a new and virile competitor for Woman’s Budget. The Telegraph’s editor, Thomas Dunbabin, also observed that the Women’s Weekly’s effect “on the Women’s Sections of our Dailies should be closely watched, and… a careful note made of what it demonstrated in respect of what women want.” The success of the Weekly, he went on, “shows a tremendous demand for certain things on the part of women.”

The Fairfax archive documents the negotiations that led to Frank Packer’s company, Sydney Newspapers Ltd, joining with Associated Newspapers in 1935 to form a new company, Consolidated Press Ltd, and relaunch the morning Telegraph as the Daily Telegraph the following year. The intricacies of calculating the value of their respective titles are recorded, including notes of phone calls to Packer, and discussions about what should (and shouldn’t) be revealed to shareholders. The files include agreements to contain competition in order to protect the jewels in the respective companies’ crowns: the Women’s Weekly on one side, and the afternoon Sun and the Sunday Sun on the other.

Thanks to the State Library team headed by Peter Arfanis, I now know that the Fairfax archive also contains files on competitors throughout the decades, including ACP and the Daily Telegraph in Sydney; the Herald and Weekly Times, headed by Sir Keith Murdoch; and News Limited, headed by Murdoch’s son Rupert. I’m intrigued to look at a file entitled “Daily Telegraph — Misdemeanours, 1957–1962,” which apparently contains “memos and newspaper clippings of lifting of stories etc.” Back in the 1990s, I found in the records of successive Fairfax general managers particularly valuable accounts of the competition, and intermittent collaborations, between Fairfax, ACP and their mastheads.

The big publishing companies in Australia realised that it was indeed sometimes beneficial to work with each other. In 1932 Warwick Fairfax (later Sir Warwick) and Keith Murdoch formed a company in Tasmania with the aim of producing Australian newsprint. The result, six years later, was a new business, Australian Newsprint Mills, owned by eight publishing companies. Well over a dozen boxes in the Fairfax archive document the operations of this endeavour, in which the two Herald groups were the dominant, if not always harmonious, partners, as they battled to deal with restrictions on their lifeblood during the war and postwar periods.

Meanwhile, Australian Associated Press was created in 1935 out of an amalgamation of the Australian Press Association, run by Fairfax and the Melbourne Argus, and the Sun Herald Cable Service. Numerous boxes in the Fairfax archive show the operations of the Australian Press Association and AAP, as well as negotiations with Reuters in London.

From the mid 1920s the Australian Newspapers Conference also considered matters of mutual interest, such as cover prices, advertising rates and industrial negotiations. Following a dispute involving the 1941 launch of a new afternoon paper, the Daily Mirror, during acute newsprint rationing, the ANC was disbanded and replaced by the Australian Newspaper Proprietors Association. The Fairfax archive contains substantial records of the ANPA, especially concerning the operation of its newsprint pool during the second world war, with periodical eruptions from the volatile Packer, and delegations to Canberra. Likewise, the archive documents the operations of the reconstituted Australian Newspapers Conference that was formed in 1955. I look forward to ordering up the files containing annual reports of the ANC’s “Joint Committee on Disparaging Copy,” which seemed to run until the 1980s.

Through the archive we can trace the April 1944 dispute that saw the Curtin Labor government censor, before publication, the articles of several Sydney newspapers; Packer’s subsequent decision to print the Sunday Telegraph with blank spaces; and a High Court challenge.

I went back to the Fairfax archive to research my third book, Party Games: Australian Politicians and the Media from War to Dismissal (2003), as well as my Australian Dictionary of Biography entry on Sir Warwick Fairfax. By now the archive had moved to Alexandria, where the City to Surf organisers were headquartered.

One particularly rich file I identified with the help of Fairfax library staff was called “Herald & Weekly Times Ltd from Jan. ’33 onwards.” Running until the death of Keith Murdoch (“Lord Southcliffe,” as he was sometimes called) in 1952, it provided insights into his health battles; the newspaper companies’ hostility to the prospect of an independent news service being run by the ABC; the regulation of commercial radio broadcasting; and discussions with politicians and party officials. Here is Murdoch in 1935 corresponding with Sir John Butters, chairman of Associated Newspapers, about the ABC:

Thank you for your confidential letter… I am so glad that you are moving in this matter. It is high time that we took serious notice of it. The A.B.C. is regarding even its legal agreements with us as trifling. It is spreading itself into many areas of news…

I think our movement should be a quiet one. We should put our views confidentially to the Prime Minister, and also to one or two other Ministers, particularly McLachlan, Parkhill, and Menzies.

Shades of the current inquiry into the competitive neutrality of the ABC and SBS…

Likewise, a 1954–67 file about Sir Warwick Fairfax yielded a rich seam of gold, with observations such as this from 1957: “I heard [Harold] Holt speak in the Foreign Affairs debate and he was dull, pompous, boring and irrelevant to the last degree. I completely fail to see him as a possible Prime Minister.”

The fourth chapter of Party Games, entitled “The Labor Ward: The Fairfax Dynasty and the 1961 Election,” dealt with the company turning against the Robert Menzies’s Coalition government over its deflationary measures, and working closely with the Labor leader, Arthur Calwell, on his campaign. Few Australian historians could fail to be intrigued by some of the titles of files in the archive Gavin and later I worked on, including “Liberal Party 1944–1969” and “Labor Party 1950–1969.” These contained details of private discussions, donations, internal company debates, election coverage and political broadcasts. Thanks to the work of Peter and his team, I now have a better sense of just how much material there is in the archive concerning federal and state politics and elections, including this file covering 1940 to 1984: “Correspondence Prime Ministers and Departments.”

Since my research in the Fairfax archive in the 1990s, I have been intrigued by the evolution and fate of Associated Newspapers, a company and a name that few may remember. I chose to write the entry on the company for my edited collection, A Companion to the Australian Media, drawing on the research that Gavin and I had undertaken for our company histories. We had each traced the offers of Fairfax and Consolidated Press to buy the ordinary shares in Associated Newspapers in 1953, motivated by the desire to be in a position to use idle printing capacity by publishing an afternoon newspaper (the Sun) as well as their existing morning paper (the Sydney Morning Herald or the Daily Telegraph). In other words, to borrow the words of Greg Hywood and Hugh Marks, they wanted “scale.” The board of Associated Newspapers, remembering how two generations of the Packer family had exploited their fears about competition in the 1930s, accepted the Fairfax offer.

Tiles from the Sun Newspapers Ltd building, Sydney, c 1929, depicting Phoebus Apollo driving a seven-horse chariot out of the rising sun. Fairfax Media Business Archive, State Library of New South Wales

Frank Packer spent three years unsuccessfully challenging the validity of the merger. Amid the documentation in the archive is humour, such as in an exchange of several sly telegrams between Rupert Henderson and Packer in the Spring of 1953. The last one from Packer, addressed to Henderson at “ASSASSINATED NEWSPAPERS LTD,” read, “CONGRATULATIONS ROUND ONE STOP BY THE WAY DID YOU PLAY WITH THE JUDGE OVER THE WEEKEND.”

As I recently wrote in the Conversation, competition may seem an obvious — perhaps the obvious — feature of the Australian media landscape, but it has gone hand in hand with pragmatic cooperation. Even if the Fairfaxes, and Keith Murdoch in Melbourne, failed to regard the pugnacious Frank Packer as a gentleman, there was a kind of gentlemanly code of honour, and understanding, between the knights of the Australian media. If the early relationships between the three groups focused on daily and Sunday newspapers, and magazines, their ancillary, and expanding, media interests led to cooperative agreements. In Souter’s work on Fairfax, and my work on Packer, we were able to draw on the Fairfax archive to help trace how the media groups obtained television licences from 1956 onwards.

Before the Australian Broadcasting Control Board’s 1958 hearings for applications for licences in Brisbane and Adelaide, the main Sydney and Melbourne television proprietors — Packer, “Rags” Henderson from Fairfax, and Sir John Williams from the Herald and Weekly Times — met at Fairfax headquarters to “carve up the empire.” The archive helps to demonstrate how they reached an agreement to combine their interests to ensure an equitable program-sharing arrangement if there should only be one licence awarded in each city.

In 1960 Murdoch’s only son, Rupert, entered Sydney through the back door by buying the suburban newspaper chain Cumberland Newspapers Pty Ltd for £1 million. Vowing not to let this invasion go unchallenged, Fairfax and Packer contributed equal capital to form a new joint company, Suburban Publications Pty Ltd, whose records are held in the Fairfax archive. The vigorous, at times farcical, competition between the two suburban chains did not last; as Souter deftly noted, “war was being waged in the suburbs, but it was limited war.” In 1961 Cumberland Newspapers and Suburban Publications concluded a “Brisbane Line” non-compete agreement that would not have been permitted under the Trade Practices Act that became law in 1974.

The Fairfax archive also documents aspects of the history of Australian radio and television. It holds the paper records of the powerful Macquarie Broadcasting Network and ATN-7, which was one of Sydney’s two original television stations. (Frank Packer’s TCN-9 was the other.)

So I was back in the archive to research my fourth book, Changing Stations: The Story of Australian Commercial Radio, which was published in 2009. Having progressed to a laptop, I made 283 pages of single-spaced notes ranging across the Herald’s supply of news to the Macquarie News Service; the appointment of commercial radio’s first cadet journalist, Brian White; arrangements for sports, finance and election coverage; the pre-election blackout; hours of transmission; the spread of midnight-to-dawn programs; the emergence of Top 40, talkback and FM radio; advertising; and ratings.

Station strategies and overhauls are documented in candid (at times amusing) detail. In mid 1981 Mike Carlton and Nigel Milan, 2GB’s young and ambitious general manager, outlined the problems they perceived. The “We Know What You Want” slogan smacked of arrogance, inviting the retort “Oh no you don’t,” they wrote. The station’s programming policy and image were “fuddy-duddy” and a “mish-mash.” Ancient, unreliable equipment caused technical problems, including the dreaded “dead air.” Accurate clocks were scarce. Morale was low. A typical employee arrived at 9.15am to find that the lift wasn’t working.

The archive also shows the role of big personalities in Sydney’s commercial radio, as evidenced by the “saga” of million-dollar contract negotiations with one John Laws. Even if personnel records may be restricted, the volume and range of other material in the archive help to illuminate the careers of Laws and fellow inductees into the newly national Australian Media Hall of Fame, including John Fairfax, Eric Baume, J.D. Pringle, Rags Henderson, Brian White, Margaret Jones, Max Suich and Vic Carroll.

I have done rather less work on television records in the Fairfax archive, which the State Library’s work shows cover the 1953 royal commission that examined the introduction of TV; the allocation of metropolitan and regional licences; the purchase of equipment; profits and losses; market research; overseas study tours; program-buying deals; the emergence of the Seven Network; and relationships with, and inquiries by, successive regulators. A box covers Bruce Gyngell’s term as managing director of the Seven network after he quit Frank Packer’s Nine network in 1969. In what was dubbed the “Seven Revolution,” Gyngell went on a buying spree and masterminded an aggressive publicity campaign that catapulted Seven to ratings supremacy.

This major Australian business and media archive will enrich so many studies of the media and beyond. There are files on Sydney Morning Herald literary competitions to delight the literary historian; in-house publications, and files on the Herald chapel, cadet training, award negotiations and strikes, for historians of labour and even of women; files on typefaces, and the move from hot metal to cold type and from typewriters to VDUs, for historians of technology; files on libel and defamation for legal historians; files on overseas offices and foreign correspondents, for international and war historians; and files on the Pitt Street Congregational Church for religious historians.

The archive will also enable new work on seriously neglected aspects of the history of the Australian media, including David Syme & Co., newsagents, suburban newspapers, popular magazines, local government reporting, printing, and news and journalism. It has unparalleled riches for the Australian press historian, with Fairfax publishing, at various times, the Sydney Mail, Pix, Woman’s Day, the Australian Financial Review, the Canberra Times, the National Times, Business Review Weekly, the Illawarra Mercury, the Newcastle Herald — and of course, by increments between the 1960s and the 1980s, the Age. Individual nuggets leap out in the catalogue, including memos about the resignation of David Marr as the editor of the National Times in 1982, and File 11 in Box 1284, entitled “Goanna (Mr Kerry Packer) and The National Times Apology, 1983–1984.”

Of course, other substantial collections complement the holdings of the Fairfax archive. These include the papers (around 160 boxes) of Caroline Simpson, Sir Warwick Fairfax’s eldest child, held at the State Library of New South Wales. The National Film and Sound Archive holds the 127-box collection of Frederick W. Daniell, an executive with Associated Newspapers and Macquarie Broadcasting. The National Library of Australia is home to the papers of Gavin Souter, as well as of Angus McLachlan, a long-time general manager and managing director of Fairfax, and in 2012 obtained an archive of around 18,000 glass plate negatives of Fairfax photos. The ACP magazines archive, which came to the State Library of New South Wales in 2008, is substantially made up of photonegatives and prints from Pix which, following its establishment in 1938, moved from the control of Associated Newspapers to Fairfax and finally to ACP.

How has Fairfax’s history been memorialised by the company itself? In 1991, the archive records, the staff of John Fairfax and Sons signed and presented James Reading Fairfax with a leather-bound illuminated address to mark his proposed departure from the colony for “a visit to the old world.” In 1912, the staffs of the Sydney Morning Herald and the Sydney Mail presented a diamond jubilee illuminated address to Fairfax — now Sir James — to mark his sixty years of service to the company. The address, which included photographs of Sir James and his family, as well as photos of staff members arranged by department, recorded:

The gift is intended not only for an expression of our esteem for you as Senior Proprietor of the Journals… It serves also to mark our personal regard for you as an employer whose kindly consideration has always been at the disposal of those engaged in your service, and… a sense of the value to Australia of your long and eminent service to the community.

Five years later, the staff presented Sir James with another illuminated address, this time marking his sixty years of marriage to his wife Lucy.

In 1929 the company published The Sydney Morning Herald and the Sydney Mail: The Two Greatest Papers in Australia, compiled by Percy S. Allen, who had been placed in charge of the office library two years earlier. For the next two years the influential librarian worked with S. Elliott Napier, a Herald leader writer, to compile A Century of Journalism: The Sydney Morning Herald and its Record of Australian Life 1831–1931, published by the company under the editorship of Warwick Fairfax.

In 1936 a dinner was held, and a booklet was produced, to mark the ninetieth anniversary of the Herald chapel, which had been formed in 1836 for the printers, type-setters, composers and other staff who worked in production. The centenary of the Fairfax proprietary of the Herald in 1941 was marked by the publication of The Story of John Fairfax, written by his great-grandson, John Fitzgerald Fairfax, as well as the establishment of a staff superannuation fund.

A special edition of the Sydney Morning Herald marking its 140th anniversary appeared in April 1971. In 1977 a long-service retirement fund was established to commemorate the centenary of the death of the original John Fairfax and was open to all members who had completed fifteen years’ service. The archive also documents the company’s involvement in 1978 the 150th anniversary of the Leamington Spa Courier, founded by John Fairfax in Warwickshire in 1828, a decade before he arrived in Sydney.

Fairfax’s biggest celebrations were reserved for the sesquicentenary of the Sydney Morning Herald in 1981, with Souter rightly noting that sesquicentenaries were rare for a settlement that was not yet 200 years old. Around three years before the anniversary, a special committee was formed under the direction of Ross Campbell Jones, the company’s marketing manager. Several archive boxes contain correspondence between management and executives, and with various companies and personalities who would be involved in the celebrations, and also document the various functions to be held and donations that would be made by the company to mark the occasion.

Among the ideas considered were a time capsule and a limited edition commemorative plate and placemats; a vinyl gramophone recording, Australian Musical Heritage, beginning with Lieutenant G.D. Callen’s “The Sydney Morning Herald Polka” from 1863; a church service, an Australian production of the opera Otello starring Joan Sutherland, a Rugby Union team, and a rodeo at the SCG; commissioning a painting by Lloyd Rees, and a television documentary by John Pilger; arranging a greeting from the Prince of Wales; and a trans-Australian hot air balloon flight. Ideas for employees’ celebrations included a function at Taronga Zoo or a staff picnic, and the purchase of holiday units for the use of retired employees. A bumper supplement appeared on 18 April 1981, and a dinner was held at the Hilton Hotel, with speeches by the governor-general, Sir Zelman Cowen, and James Fairfax captured on cassette tape in the archive.

Sculptor Stephen Walker was also commissioned “to create an association of water and bronze” in a landscaped area to be known as Herald Square, on the corner of George and Alfred Streets near Circular Quay, in 1981. Walker connected the fountain to the Tank Stream, the European settlement’s first water supply, highlighting a union between the Herald and Sydney’s European history. Correspondence, sketches and photographs document how the fountain came to feature a series of figurative and non-figurative forms made in bronze and connected by separate, linked pools. From the central cascading fountain, four columns in bronze rise out of the pool. An array of Australian flora and fauna, including frogs, snakes, goannas, echidnas, crabs, birds and tortoises appear to be playing in the pools.

The company also donated more than $100,000 towards the construction of a clifftop Fairfax walkway and lookout on Sydney’s North Head. Fairfax also, of course, commissioned Souter to write Company of Heralds, a wonderfully enduring legacy that also led to the creation of the Fairfax archive. And the Herald’s assistant editor, Lou Kepert, edited History as it Happened, based on 150 years of reporting in the paper.

Other milestones have been celebrated, such as 175 years of news in the Herald (2006), a century of Herald photography (2008), the 20th anniversary of the Herald and Age websites (2015), and the Herald’s 185th anniversary (2016), as well as anniversaries of other Fairfax titles.

In a message from the editor in the weekend Herald on 4–5 September, Lisa Davies remarked:

Many have bemoaned the looming loss of the Fairfax name from Australian publishing as the regrettable end of an era, but such nostalgia should not be exaggerated …

Readers don’t identify with a Fairfax story — it’s the mastheads like the Herald that simultaneously give consumers the story and the history, strength and power of those publishing it.

I beg to differ. It is the “Fairfax” archive that has been given to the State Library. The anniversary commemorations I’ve outlined in the last few minutes show the close relationship between the Fairfax family and their staff, and the way in which both publishing and family milestones have been marked for more than a century. Since at least the 1930s the company was connecting its own story with the story of Australia, and it’s a story that we must not forget. While the rupture caused by young Warwick Fairfax’s disastrous privatisation attempt has been much commentated on and lamented, and the death of Fairfax has been foretold in books with titles including Killing Fairfax and Stop the Presses!, it is up to us to keep the story and the history alive. A sequel, or a prequel, to the Power Games: The Packer-Murdoch Story mini-series, perhaps? ●