The 1987 election doesn’t immediately suggest itself as a moment that changed Australia. It didn’t bring a new government to office. It didn’t involve a large swing to either of the parties. It didn’t see many seats change hands. Yet it was arguably the most significant election of the 1980s and one of the most consequential in the last quarter of the twentieth century.

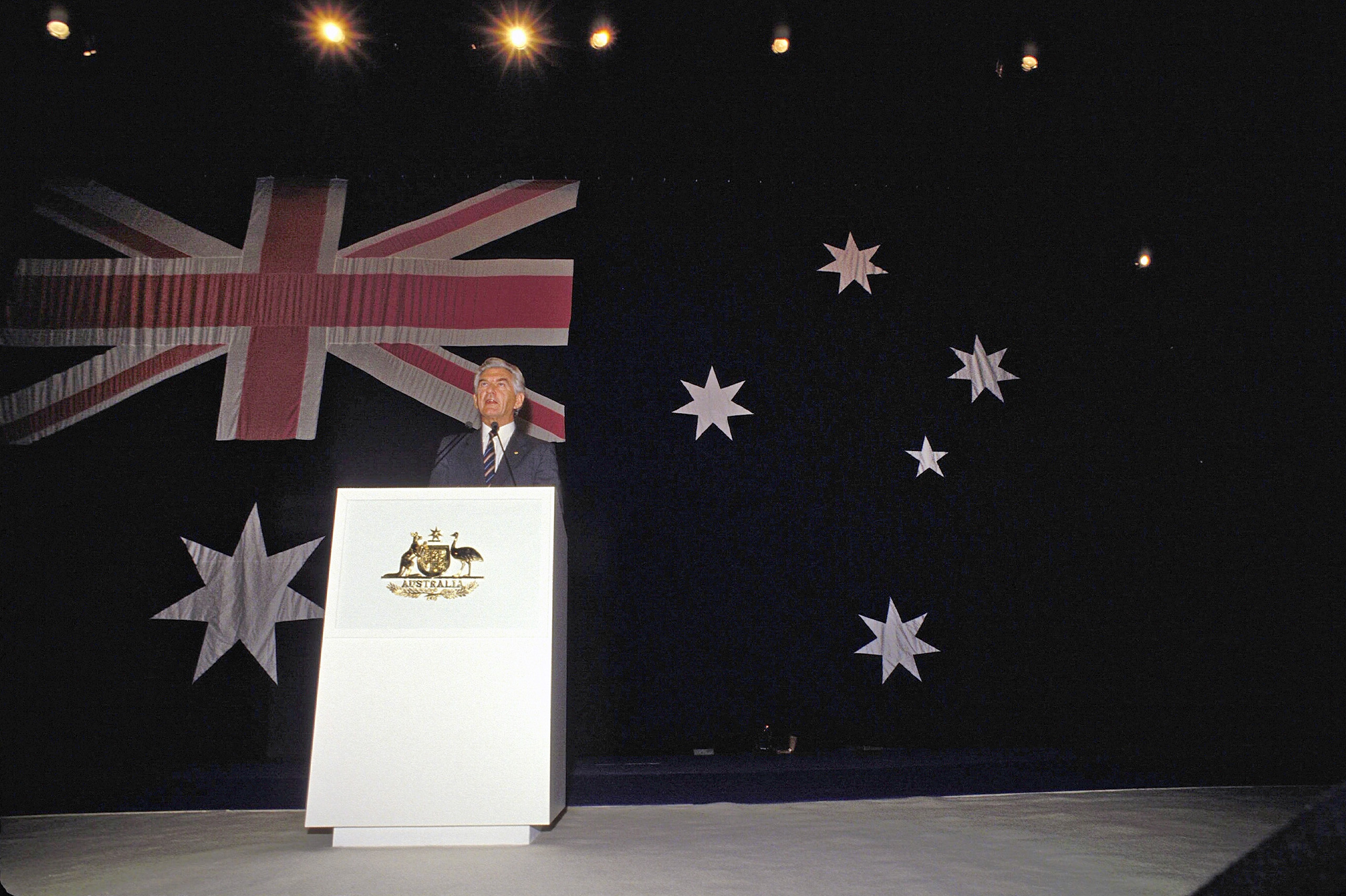

This was the election that announced, once and for all, that the Australian Labor Party under prime minister Bob Hawke was ruled by a hard pragmatism and a determination to do “whatever it takes” to win. Labor had never before won three federal elections in a row. The election was hardly less significant for the Coalition parties: it was the “New Right” election, the contest most affected by the radical conservative revolt of that decade.

The election is most commonly associated with the push by Joh Bjelke-Petersen, Queensland’s National Party premier, to transfer to federal politics and seize the prime ministership. But those ambitions were not only a product of Bjelke-Petersen’s own instability and the eccentricities of Queensland politics; they also reflected how the national New Right had outflanked the federal leader of the Liberal Party, John Howard, and mainstream conservative politics more generally, during 1985–87.

The most significant effect of the New Right’s campaign was to help extend Labor Party rule for almost another decade. It was not until the defeat of Liberal leader John Hewson’s Fightback! campaign in 1993 that the genie was returned to its bottle.

During 1985 Bjelke-Petersen had won a stunning if brutal victory over striking electricity workers in his state, one of several victories across the nation for the industrial relations hardliners associated with the New Right. After his unexpected outright victory at the Queensland state election held in November 1986 — the Nationals having discarded their Liberal partners in 1983 — the National Party was able to govern alone. John Howard, watching Bjelke-Petersen claim victory on television, turned to his wife Janette and declared with unerring accuracy, “We’ll have trouble with this lunatic now.”

He had been rumoured for some time to be pondering a switch to Canberra, a move being encouraged by a group of Gold Coast entrepreneurs known as the white-shoe brigade. These men, of whom the most prominent was the flamboyant former car dealer and property developer, Mike Gore, had a number of preoccupations. They still loathed John Howard for having introduced, as treasurer in the Fraser government, retrospective legislation designed to shut down “bottom of the harbour” tax-avoidance schemes. They also probably nursed an ambition to install the corrupt Gold Coast politician Russ Hinze as Queensland premier.

One other factor might have entered their calculations: they had little to fear from a pro-business Labor government in Canberra, some of whose leading members were openly identified as friends and supporters of such thrusting entrepreneurs.

By Christmas 1986 it was clear that Bjelke-Petersen would soon make a move. At a rally in Wagga the following month, he warned that those who did not support him and his policies would find their seats contested at the next election. The Queensland National Party powerbroker Robert Sparkes, who was quite unable to contain Bjelke-Petersen’s increasingly unhinged behaviour and inflated ambitions, felt he had little choice but to throw the weight of the state branch behind the premier.

In February 1987 a meeting of the Queensland Nationals at Hervey Bay agreed to back the Joh-for-PM campaign. They called on federal National Party leader Ian Sinclair to withdraw from the Coalition and, if he refused, for the Queensland Nationals to go their own way. At a National Party federal council meeting in Canberra in March, Bjelke-Petersen memorably thrust his arms into the air and announced the “good news” that the Coalition was finished.

By this time, he was attracting the support, or at least the praise, of prominent Australians. Geoffrey Blainey, prolific historian and media pundit, considered him “one of the quiet giants in our political history,” a man “like the legendary tortoise racing the hare.” “I think he will be a more serious challenger than most media people are suggesting,” Blainey suggested, a prediction that turned out to be accurate only in the unlikely event that he was referring to the Queensland premier’s capacity to derail his own side of politics.

In announcing the formal break-up of the federal Coalition, in March, Howard again accurately predicted that Bjelke-Petersen “will clearly go down in history as the Coalition wrecker and he has no chance of ever becoming prime minister.”

The Bjelke-Petersen thrust has sometimes been presented simply as the product of the idiosyncrasies of an ageing and corrupt megalomaniac, or of the peculiarities of Queensland politics. But even leaving aside the various agendas being pursued by his supporters, the Joh-for-PM push was rather more complicated. In fact, it was very much a product of the fluid character of Australian economics and politics in the mid 1980s.

The style of consensus politics pursued by Bob Hawke after he assumed leadership of the federal Labor Party in early 1983 had stimulated political entrepreneurship of various kinds on the right. Blainey’s campaign against the pace of Asian immigration in 1984, and the mining executive Hugh Morgan’s against Aboriginal land rights in the same year, were followed by New Right agitation in favour of anti-union and anti-arbitration industrial relations reform, lower taxes, government spending cuts, and even lower wage growth than the government had achieved via its Prices and Incomes Accord with the union movement.

At a time of rapidly declining farm incomes, a rural revolt led by the National Farmers’ Federation, with wealthy South Australian grazier and business figure Ian McLachlan at the helm, added potency to the chatter of city-based dining clubs, employer organisations and barristers’ chambers. The views of the New Right appeared frequently in the op-ed columns of the country’s newspapers, especially the Australian, and the confidence of these new militants found expression in a series of high-profile industrial disputes, culminating in a lockout of workers at Robe River on the Pilbara iron ore field in Western Australia in 1986.

While former Liberal leader Andrew Peacock had performed creditably at the 1984 federal election, with the Coalition reducing Labor’s majority in an enlarged House of Representatives, his leadership didn’t survive the rivalry with John Howard, who replaced him the following year. Howard had every reason to hope that the intellectual influence being exercised by the New Right outside the parliament would help him to reshape the political agenda. Having rather unfairly borne much of the opprobrium for the perceived failures of the Fraser era, he wished to forge a legacy of his own that would draw to some extent on the kinds of free-market policies being pursued in Britain by Margaret Thatcher and in the United States by Ronald Reagan.

The Liberal Party divided into a “dry” faction, which supported this direction and was influenced by the ideas of the New Right, and a “wet” faction that identified more strongly with a statist tradition that some traced to the early prime minister Alfred Deakin. The latter looked more to Peacock than Howard as favoured leader.

Peacock’s name, however, was also mentioned in connection with the Joh-for-PM push, underlining the role of personal rivalries and animosities beyond whatever ideological differences existed on the conservative side of politics. Howard’s problem was that his leadership was being destabilised from within as well as from without, where he was being outflanked by an increasingly adventurous New Right.

Labor had been behind in the polls in late 1986 and early 1987, and party insiders, who revealed after the election that Labor had been trailing by eight percentage points just ten months before, clearly expected defeat. The government had experienced a most difficult year in 1986, when the bottom had fallen out of the dollar and Keating had warned that unless Australia was able to turn itself around it faced a future as “a banana republic.”

A document drafted for the party’s campaign committee in October 1986, based on commissioned market research, reported “seething anger and resentment” in middle Australia about the government’s economic management. Labor’s traditional supporters seemed to think the government was deriving “a sadistic pleasure out of their hurt,” as if they were receiving “deserved punishment.”

But by May 1987, with the economy showing many signs of improvement and Howard’s leadership being destabilised by the Bjelke-Petersen push and continuing “wet” disaffection, Labor was beginning to overtake the opposition in the polls. An economic statement announcing a $4 billion cut in the budget deficit, delivered by treasurer Paul Keating on 13 May, gained a favourable reception in the media and polls. Just two weeks later, Hawke secured a double dissolution election for 11 July.

Keating has claimed much of the credit for the decision to go to an early election, an indication of the significance he attaches to the subsequent victory as the moment when the government’s place in Australian political history would be decided. Hawke, understandably, presents the decision as his own doing, the timing of elections ultimately falling within the prime minister’s prerogative.

Bjelke-Petersen was in the United States when the election was called. This famously shrewd political operator badly underestimated the temptation to an early election that his own erratic behaviour had posed. After returning to Australia and failing in an effort to secure the support of the National Farmers’ Federation, he made himself look even more foolish by announcing that he would not be going to Canberra after all. Howard flew to Brisbane and managed to secure a joint statement with Bjelke-Petersen that they would agree to work together to defeat the government; but Bjelke-Petersen candidates ran in several seats where there were already official opposition candidates, confusing voters and contributing to a sense of chaos on the conservative side of politics.

As the campaign got under way, the new ruthlessness and professionalism of the Labor Party was nowhere better illustrated than in its decision to replace its previous advertising agency, Forbes MacFie Hansen, with John Singleton Advertising. Singleton, not widely regarded as a friend of the Labor Party, was known for his role in undermining the Whitlam government with an unpleasant campaign in 1974. But the choice, for which Hawke took full credit in his memoirs, was an inspired one, giving rise to a campaign slogan that seemed to capture the feelings of many voters towards the government.

“Let’s stick together” might have been the title of a Bryan Ferry song, but in this case it was followed by an exhortation “Let’s see it through.” Just what “it” was, the jingle didn’t really specify, but the balance of payments crisis and plunge of the dollar during the previous year seemed a fair assumption. Electors received the advice that “nobody ever got anywhere changing horses in midstream” — although Labor had clearly thought otherwise when it hired Singleton.

The other piece of advertising genius that emerged from this campaign was “Whingeing Wendy,” as she became known, or Wendy Wood. She was the wife of one of Singleton’s friends and sometimes featured on Singleton’s radio program as a character named Beryl Timms, a rough but honest working-class everywoman. Wood was a committed Labor supporter and when she looked into the camera and asked in her broad Australian working-class accent where John Howard was going to find the money to pay for his tax cuts, she looked and sounded as though she really meant it.

The Labor campaign didn’t go off without a hitch, but Hawke’s only major error — the promise that “by 1990, no Australian child will be living in poverty” — was not one for which he would pay heavily in the short term. The line appeared in the speech by mistake; Hawke was apparently supposed to say that because of the government’s new family allowance supplement, there “would be no financial need for any child to live in poverty.”

Perhaps Hawke was overreacting to the accusation, increasingly heard by 1987, that this was not a real Labor government but one for the wealthy and powerful. The family allowance supplement was the product of collaboration between Hawke, Keating and left-aligned social security minister Brian Howe, and it was shaped by policy advice from the social policy academic Bettina Cass.

As a conspicuous effort to assist low-income earners, it was especially timely. Despite the sacrifices the government was demanding of ordinary voters, the very wealthy seemed to be doing better than ever. That year’s Business Review Weekly Rich List announced Australia’s first two billionaires, Kerry Packer and Robert Holmes à Court, and the stock market was booming. Hawke’s praise during the campaign for business figures such as Packer and Alan Bond, and their apparent endorsement of him, would contribute to a growing chorus of criticism about “rich Labor mates” in the years ahead, criticism that bit especially once the stock market collapsed in October 1987 and many of yesterday’s heroes became today’s shysters.

But for the time being, Labor’s families package and Hawke’s extravagant promise about ending child poverty might have helped convince some wavering voters that the government still had a Labor heart. Laurie Oakes judged that the $300 million family payment “should really be called Labor’s social conscience package,” a measure aimed at getting “rid of the idea that Labor is no different from the Liberal Party in its values.” There had been a flirtation with the idea of providing a payment for all parents with children under six. But in the straitened economic times, the government did not pursue this option, a brave decision in view of the need to keep middle-income voters onside.

The Liberals’ campaign errors, by contrast, were costly. Their campaign was disorganised, with the state branches exercising considerable autonomy tempered by minimal central direction until near the end. They went to the election advocating drastic cuts to income tax, notably a top rate reduced to 38 per cent, in contrast with Labor’s recent decision to cut the rate to 49 per cent. They also promised to reduce company tax rates, abolish the capital gains tax introduced by the Hawke government, make employees rather than their bosses responsible for paying the fringe benefits tax, and make business entertainment tax deductible.

Bjelke-Petersen, advised by John Stone, a former treasury secretary now sitting as a Queensland National Party senator, advocated a flat income tax of 25 per cent, which might have made the cuts being offered by Howard look moderate if anyone truly believed that Bjelke-Petersen was likely to cut rates so drastically. But Howard was vague about which expenditure he was going to cut to pay for his tax policy, and in any case the plan was to phase in such cuts over several years, thereby raising questions about their feasibility. Financial journalists smelt political opportunism, while voters — encouraged by Labor advertising — had reason to wonder where the money was coming from.

But the Liberals soon faced additional problems. Keating accused them of a major arithmetical error amounting to $1.5 billion, a piece of double counting that meant that funding cuts to the states were likely to be even more severe than those being proposed. Howard and his shadow treasurer, Jim Carlton, admitted the mistake. There were other gaffes in the campaign but this one — perhaps the kind of error likely to be made by a party distracted by the Joh-for-PM crusade — was the most damaging of them all.

By contrast, commentators from both left and right were increasingly in awe of Labor’s political professionalism. NSW planning minister Bob Carr, admittedly a Labor partisan, thought the campaign Labor’s “best-ever peacetime effort.” He went on: “With the panache of a Menzies, Bob Hawke persuaded the swinging voters that the issue in this election was not the record of the government but the performance of the opposition.” Pro-Liberal commentator Gerard Henderson agreed: Hawke won the election “because the ALP is Australia’s only truly professional party.”

The media was also largely on side; where once Labor could count on opposition from the press, at least in editorials, it now benefited in most cases from either support or neutrality. It was the Liberal and National parties that were now more likely to complain of media bias, but journalists could respond that they were not inventing the stories of division and confusion within the ranks; these were plain for all to see.

Issues that had once posed dangers to Labor, such as the perception that it was insufficiently committed to the alliance with the United States, had dissipated. During the 1987 campaign, US ambassador Bill Lane announced “the past year” as “one of the best bilateral relationships in the thirty-six-year history of ANZUS.” As a result of scheduled arrangements, Hawke’s close friend, secretary of state George Shultz, visited Australia with defense secretary Caspar Weinberger during the campaign, providing welcome photo opportunities for Hawke, foreign minister Bill Hayden and defence minister Kim Beazley.

But it was not just that Hawke himself was engaged, focused and indefatigable, performing far better than in 1984 and seemingly gaining new energy from the daily campaign round. It was also the skill of the party machine itself: Bob McMullan, as party secretary in Canberra head office, pollster Rod Cameron, and the advertiser John Singleton were influential members of a formidable campaign team. McMullan and Cameron were also central to the formulation and implementation of what former Hawke staffer Stephen Mills has called an incumbency strategy. It was no longer just a matter of such figures becoming active at campaign time. They were also involved in government between elections, helping to develop a plan for winning the next election and remaining in office.

In particular, Labor successfully targeted marginal seats — those it held by a slender margin, such as several in Victoria, and those it hoped to win elsewhere, such as in Queensland — and with considerable success. As journalist Paul Kelly put it, Labor “focused during the campaign on the swinging voter and it got the swing where it mattered.”

McMullan gave a young party organiser, Gary Gray, the responsibility for marginal seats. Gray then proceeded to spend a quarter of a million dollars on computers capable of storing the details of voters in each target electorate, and laser printers that would, at the mighty rate of four pages per minute, produce letters for direct mail-outs. These went into eleven of the most marginal seats. The party also installed another newfangled device, the fax machine, in the offices of marginal seat candidates to ensure rapid communication, especially when the prime minister’s travelling circus was visiting the electorate. The research, planning and technological support that underpinned Labor’s 1987 campaign victory was, by Australian standards, unprecedented and prodigious.

Superficially, the outcome might have seemed undramatic, but the numbers told only a small part of the story, especially in the context of modern Australian political history. Labor had shaken off a sense that it was “the party of occasional government.” While leading commentators resisted the idea that the party had become the natural party of government, there was a feeling that a “historical pattern” had “been broken”; that in the not-too-distant past, in such an economic situation, Labor would have faced electoral annihilation. Hawke’s “return defied all established nostrums of Australian politics,” according to David O’Reilly in the Bulletin. “He ran on his record, in winter, and promised the electorate almost nothing.”

The Coalition achieved a small swing in the two-party-preferred vote of 1 per cent. But even if that had been uniform, it would have been insufficient to get the opposition parties over the line, since Labor’s buffer was 2.3 per cent. As it happened, the Liberals and Nationals failed to achieve a swing in marginal seats that they needed to win, with the result that Labor picked up four extra seats, increasing its tally from eighty-two to eighty-six.

In New South Wales, the Liberal and National parties gained swings of between 5 per cent and 7 per cent in seven safe Labor and two safe National Party divisions — votes that were of no use whatsoever so far as winning seats was concerned. In these places, where there were seats to be won or lost, Labor’s complicated message — that the country was in economic difficulty and that it was the best party to deal with the problems — appears to have gained sufficient traction to get the government over the line. The chaos unleashed by Bjelke-Petersen in Queensland also appears to have benefited Labor, which picked up four seats in that state, more than making up for losses of a seat each in Victoria and New South Wales.

There was widespread agreement that division within the Coalition ranks had cost them dearly. Michelle Grattan of the Melbourne Age saw Hawke’s victory as a “tribute to the electorate’s common sense, and a vindication of the political adage that division is death.” Some post-election commentators rightly praised John Howard for his courage and grace under pressure, but they were uncomplimentary about his team. The shadow treasurer, Jim Carlton, was widely blamed for the accounting error, but in reality the Coalition had failed to devote sufficient time to getting its policies right. As the Australian Financial Review put it, there was too much that smacked of “half-baked policy proposals, ill-digested responses and just plain garbage.”

The Liberals went to the election with a messy policy of undoing Medicare’s universalism and pushing all but the poorest and the most vulnerable into private health insurance. The proposal to charge families for the first $250 of their medical bills each year contributed to an impression that they could not be trusted on health. The elections of 1990 and 1993 further entrenched this idea, to the enormous electoral cost of the conservative parties.

It has been suggested that perhaps a fifth of voters changed party from 1984, but there was very likely a cancelling out of most votes as defectors from each side switched allegiance. This perhaps reflects the degree of confusion that had come to surround party voting by the mid 1980s as well as the fierceness of competition between the parties. Yet, although it could not be fully realised at the time and would become clearer in 1990, there was a gentle hint here of a future in which the major political parties would become more dependent on fragile, shifting and shrinking coalitions of voters assembled for the purposes of winning each election. And where Hawke’s performance had been widely criticised in 1984, this time there was more agreement that he was an asset to the Labor Party, accounting for 1.4 per cent of the vote that would have gone elsewhere, according to one estimate. His approval rating was twenty points ahead of Howard’s.

If 1987 might be seen as representing a symbolic break of the Labor Party with the past as it steered its course through increasingly adventurous market reforms, the same was even more true of the Liberal Party. For the Liberals, the 1987 election was, in generational terms, arguably the last election of the Fraser era. The divisions of the period greatly weakened Ian Sinclair, one of three key Fraser allies in the National–Country Party (the others being Doug Anthony and Peter Nixon), and he would lose the leadership at the same time as John Howard was overthrown in 1989.

There would also be a move after the 1987 election against several Liberal progressives — or “wets” — such as Ian Macphee, who lost preselection, while figures who would figure in the Howard government, including Peter Costello and Kevin Andrews, would enter the parliament at the beginning of the 1990s. Alexander Downer, later to become Australia’s longest-serving foreign minister after a brief and inglorious time as party leader, was the Liberals’ young shadow environment minister in 1987, seeking to sell a policy that wanted to shift responsibility for most matters in his portfolio to the states — and then condemning the very same policy soon after the election.

A major figure from the Fraser era, Andrew Peacock, would be marginalised in the 1987 election, and was widely rumoured to be flirting with the Joh-for-PM campaign; he would live on to fight another day as leader when he pushed Howard out in 1989, but would fail in 1990 as Howard had done in 1987. Joh Bjelke-Petersen would soon lose the premiership of Queensland and, at the hands of the Fitzgerald royal commission, what remained of his reputation as well.

But for the time being, in the immediate aftermath of the election, there were some true believers. Des Keegan, a New Right commentator in the Australian and conspicuous Joh-for-PM supporter, would not let go, declaring that “the Coalition was invited, cordially invited, to join the anti-socialist drive with Sir Joh. Jealous of potent promise, it spurned a winning offer.”

In retrospect, it seems marvellous that apparently sensible people offered their warm commendation and support to the Queensland premier’s blatant charlatanism, but it is easy to underestimate the strains of utopianism in the New Right during this era, the extent to which the Hawke government had created confusion among such people, and the enormous capacity of some of them for self-delusion and wishful thinking. After the election, however, most commentators thought Bjelke-Petersen’s often unhinged and always self-centred behaviour had deeply damaged the conservative cause. John Howard, for one, devoted the remainder of his long and fruitful career to ensuring that he would never again suffer anything resembling the debacle of 1987.

The issue that had triggered the double dissolution election, the Australia Card, barely figured in the campaign. This was a foolish omission on the part of the opposition parties, because public opinion was turning against it. One post-election commentator remarked that the failure of the Liberal Party to make anything of the issue suggested “the same lack of interest, if not contempt, for civil liberties as the Labor Party.” A more likely explanation is that the Coalition simply failed to register the potential potency of the issue in a climate in which economic matters seemed the most pressing. As it happened, the government abandoned its plans for the Australia Card before the end of the year.

The disarray in conservative politics that the 1987 election both reflected and compounded had powerful implications for Australian political history. This was an election that mattered. Labor’s victory meant that it could press on with policies that, for its critics on the broader left, often amounted to the slaughter of sacred cows. Reform of the university system, including the reintroduction of fees, tariff cuts, privatisation and a move towards more decentralised industrial relations all followed the election.

While the Coalition would have travelled down much the same path — possibly faster and further — if it had won the election, Labor’s victory meant that market-friendly reforms would be tempered by social and welfare spending of a kind to which the Coalition parties remained unreconciled throughout the 1980s. For instance, when the Labor government moved to reform the university sector, it pursued a middle way by introducing a system of income-contingent deferred fees payable through the taxation system, rather than attempting a more vigorous shift towards full fee-paying or even a privatised system — something that the conservative parties may well have attempted if their 1987 policies are any guide.

Labor’s electoral longevity also helped ensure that when the shift away from centralised wage determination occurred in the late 1980s, the unions were able to retain a central place in the system as agents in a collective, or enterprise, bargaining process. Through the Prices and Incomes Accord, they would play a major role in shaping compulsory superannuation. Labor’s success in 1987 — and its further victories in 1990 and 1993 — also preserved another policy that had been part of the Labor Party’s agreement with the unions when it came to office in 1983, the system of health insurance called Medicare.

The final years of the Hawke government, between 1987 and 1991, saw a decisive move towards stronger environmental protection. While Labor had a good record in this area, stretching back to its success in preventing the damming of the Franklin River in Tasmania in 1983, the style of pragmatism that Labor had displayed at the 1987 election was critical in shaping its future actions. Labor courted conservation groups in the lead-up to the election, with right-wing powerbroker Graham Richardson, who would become environment minister after the election, instrumental in this effort. The Coalition’s policy, by contrast, was to return environmental issues largely to state government control.

Commentators puzzled after the 1987 election about whether Labor’s success represented a decisive break with the patterns of twentieth-century electoral competition, which had seen the non-Labor parties dominate. Thirty years on, it is still not entirely clear whether this was the case, since the Coalition has dominated federal politics since the end of the Hawke–Keating era. Increasing party competition, manifest especially in the growing number of marginal seats, ensured that Labor’s ascendancy rested on much shakier foundations than the hegemony of the Menzies government. Labor’s share of the primary vote dropped from 49.5 per cent in 1983 to 47.5 per cent in 1984 and 45.8 per cent in 1987, and it then dipped below 40 per cent in 1990. As a result, the government became increasingly dependent on the preferences of minor parties.

How would modern Australian politics have been different if the Coalition had won the 1987 election? Inevitably, counterfactual history is a dangerous business, but the following scenario seems plausible. John Howard would probably have governed for two terms at least — the normal minimum since the demise of the Scullin Labor government in 1931 — but a Coalition government would then have faced the challenge of guiding Australia out of a recession in the early 1990s.

In the meantime, Howard is likely to have drastically cut expenditure in the effort to pay for his tax promises at the 1987 election and then balance the books in the context of declining economic activity from around 1990, as Australia entered a recession. With an empowered New Right outside parliament — and, no doubt, increasingly well represented in it — supporting even lower taxes and lower spending, the pressures for dry economic policy and aggressive anti-union measures would have been powerful.

The Liberal Party had decided not to take a consumption tax to the 1987 election, but perhaps it might have found it necessary to do so in 1990 or 1993, in the face of declining tax receipts from other sources. Having already abolished Medicare as a universal health scheme, a Coalition government is likely to have sought to reduce health expenditure even further after 1987, and to have pursued a more aggressive policy of inserting market forces into higher education, as well as faster and more far-reaching privatisation of government assets.

All the same, the Coalition would still have faced the barrier of the Australian Democrats in the Senate, a moderating influence, as well as resistance from a union movement that in 1990 represented about 40 per cent of the paid workforce. The Coalition might have lost government either in 1993 or in 1996. Perhaps a more experienced John Hewson, fresh from his ordeals as treasurer in a Howard government, might have emerged as opposition leader against a Labor government led by Kim Beazley. It is hard to imagine Paul Keating having endured many years in opposition after his time as treasurer.

These are mere speculations; and, in truth, given the extent of agreement between the major parties in economic and foreign policy by the 1990s, the differences might not have been great in the end. Perhaps Australia would have had a WorkChoices-style industrial relations policy in the 1990s, but this would have been unlikely without conservative control of the Senate. Possibly a later-1990s Labor government might have been able to advance the cause of an Australian republic, but the same divisions as actually occurred in 1999 over the most appropriate model would not have evaporated with the career of John Howard.

Nonetheless, even amid the uncertainties of counterfactual history, it is clear enough that there would have been greater pressures on a 1980s Australian social model that sought to balance freer markets and higher profits with a reasonably generous welfare state, environmental protection, and a continuing role for unions in industrial affairs. To that extent, 1987 was an election that mattered, one which ensured that even during a period of rapid global transformation, Australia tended to cleave to a middle way. •

This is an extract from Elections Matter: Ten Federal Elections that Shaped Australia, edited by Benjamin T. Jones, Frank Bongiorno and John Uhr, published by Monash University Publishing.