Anthony Albanese wants to make industrial relations the key issue at the next federal election, which could take place later this year. While he hopes to take the focus away from Australia’s relative success in managing the pandemic, Covid-19 has itself been a “great revealer” of economic inequality.

Workers in insecure employment were often the first to lose their jobs. Low-paid, precarious work has helped spread Covid-19, with poorly paid hotel security guards forced to work second jobs and other struggling workers finding it difficult to take time off even if they may have been exposed to the virus or have minor possible symptoms. All of this has served to highlight the prevalence of low-paid and precarious work in the Australian economy

Meanwhile, despite the government’s earlier promises of setting aside ideology and working cooperatively with unions, the ACTU argues that the Coalition’s proposed industrial relations legislation will actually increase insecure work and facilitate wage cuts.

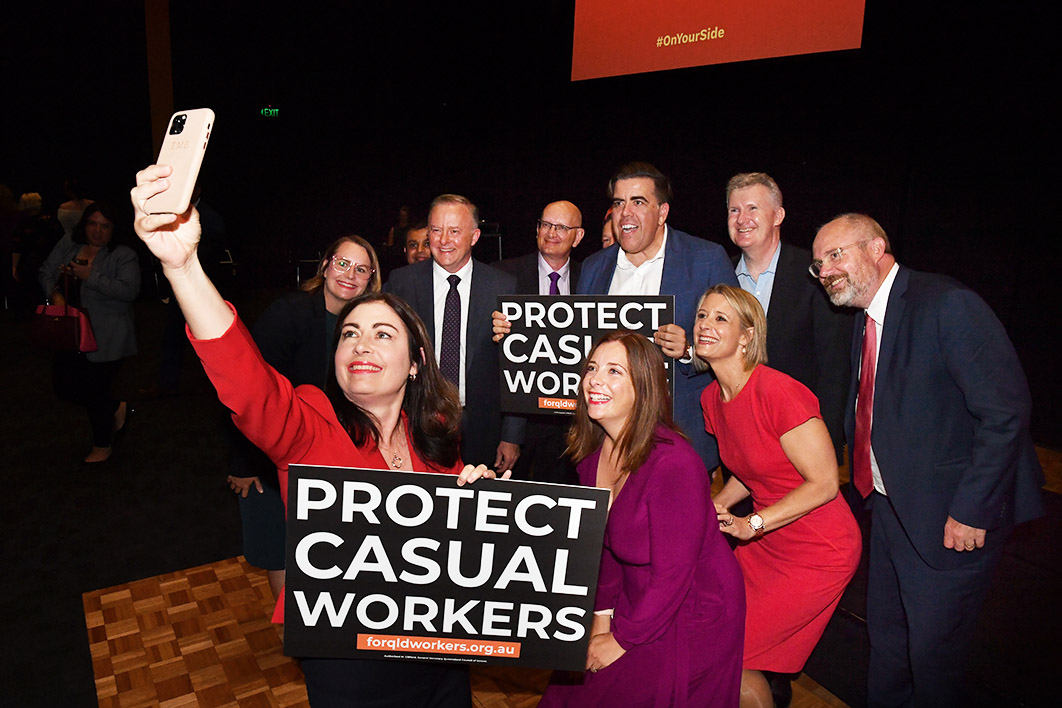

It all seems fertile ground for a party that last defeated a sitting Coalition government at least partly by campaigning against John Howard’s WorkChoices legislation. Albanese no doubt hopes that a focus on industrial relations will also shore up his leadership and reduce dissension among Labor party members and MPs who claim Labor has been neglecting its working-class base. His focus will be on creating more better-paid, secure jobs while expanding access to employee entitlements and ensuring those entitlements are portable in insecure industries.

To this end, the Labor leader proposes a Hawke and Keating–style compact between business and labour, arguing that “the best governments in our history have understood the need for a compact between capital and labour to advance their mutual interests.” The argument aligns with Albanese’s view that Labor’s populist rhetoric against the “big end of town” was one of the reasons it lost the 2019 election. “The language used was terrible,” he argued at the time. “Unions and employers have a common interest. Successful businesses are a precondition for employing more workers.” As I argued before the election, widespread business opposition will hurt Labor if voters become concerned that private sector investment, and consequently jobs, will be at risk.

But Albanese faces a number of obstacles. To begin with, the Hawke-era consensus between business and unions rested on an Accord process that traded wage restraint, and increasingly real wage cuts, for a compensatory “social wage” in the form of increased government services and benefits. In other words, it was based on businesses paying lower wages than they otherwise would. The introduction of enterprise bargaining also saw reductions in workers’ conditions. No wonder many businesses were favourably disposed.

By contrast, Albanese will be attempting to develop a compact between business and labour based on higher wages and better conditions. Some far-sighted businesspeople, especially in highly profitable industries, may see the advantage that higher wages and more secure employment will have in increasing consumption. After all, the Reserve Bank has long argued that the fall in consumption due to wage stagnation is a significant problem for the Australian economy. But other sections of industry might not wish to increase the wages and conditions of their own workers in difficult economic times.

Despite Albanese’s criticisms, Bill Shorten also argued that wage increases would be a “win-win” for business, workers and the economy in general. But he still faced significant resistance from business. Predictably, Albanese’s IR plans have already elicited major business opposition. For its part, the government claims that Labor’s policy would cost business $20 billion, extinguishing many firms and jobs in the process.

Labor has a history of critiquing some sections of capital while supporting others. Prime minister Ben Chifley demonised the banks and prime minister Gough Whitlam the multinationals, but both supported Australian manufacturing. Albanese seems to be focusing on critiquing the gig economy while hoping to win over other businesses by supporting industries that offer better pay and more secure conditions and offering them preference in government contracts.

Even this could backfire. Rideshare drivers and food deliverers currently suffer the most obvious effects of “Uberisation,” but many other industries could introduce precarious app-based employment. Numerous tasks could also be competitively outsourced via platforms such as Airtasker, including to workers in lower-wage countries. And a range of industries already use the labour-hire measures that Labor is also targeting.

Albanese therefore faces two major challenges in turning Labor’s IR policies into a successful electoral strategy. First, he needs to convince business that this is another occasion on which social democracy needs to save capitalism from itself, as Kevin Rudd argued was the case during the global financial crisis. In this instance, neoliberal attacks on unions and workers, along with cuts to government benefits, have resulted in a crisis of consumption by reducing incomes and deepening inequality.

Second, Labor needs to convince workers that industrial relations reform is the best way to increase living standards. Labor attempted to do this during the 2019 election campaign, but many voters, unconvinced that Labor in government would be able to ensure higher incomes and jobs growth, opted for Morrison’s promises of lower taxes instead.

The ACTU’s Change the Rules campaign, which should have helped Labor win the election, also faced a dilemma. Some of the industrial relations rules in need of changing had been introduced not by the Coalition but by previous Labor governments. In other words, past Labor government policies have contributed to a lack of confidence in the ability of governments to improve wages and conditions. That — rather than climate change or so-called “identity politics” — was one of the major difficulties Labor faced at the 2019 election.

Whether Anthony Albanese can overcome these problems, or even save his own leadership, remains to be seen. In the meantime he hopes to make the next election “a battle for the things which matter most to Labor” and “a contest between two very different visions for the future of Australia.” In one sense he is undoubtedly correct. As a social democratic party, Labor has no choice but to try to tackle Australia’s rising inequality and the growth of precarious work. The issue is whether Labor will be able to turn that into a successful electoral strategy. •