Reading Behrouz Boochani’s No Friend but the Mountains: Writings from Manus Prison brought to mind another piece of prison literature written nearly eighty years ago. Reviewers of Boochani’s book have compared it to other examples of prison literature, but none have mentioned the work that resonated with me: The Prison Diary of Ho Chi Minh, written in 1942–43.

No Friend but the Mountains was smuggled out of Manus Island in the form of tweets, text messages, emails and phone videos, and translated into English by Sydney University’s Omid Tofighian. Boochani writes in Farsi, a language with poetic resonance, and his translator finds his prose “rich with cultural, historical and political frames of reference and allusions.” The English text is interspersed with lyrical fragments of poetry that heighten the narrative and distil elements into dreamlike visions and compelling cries from the heart.

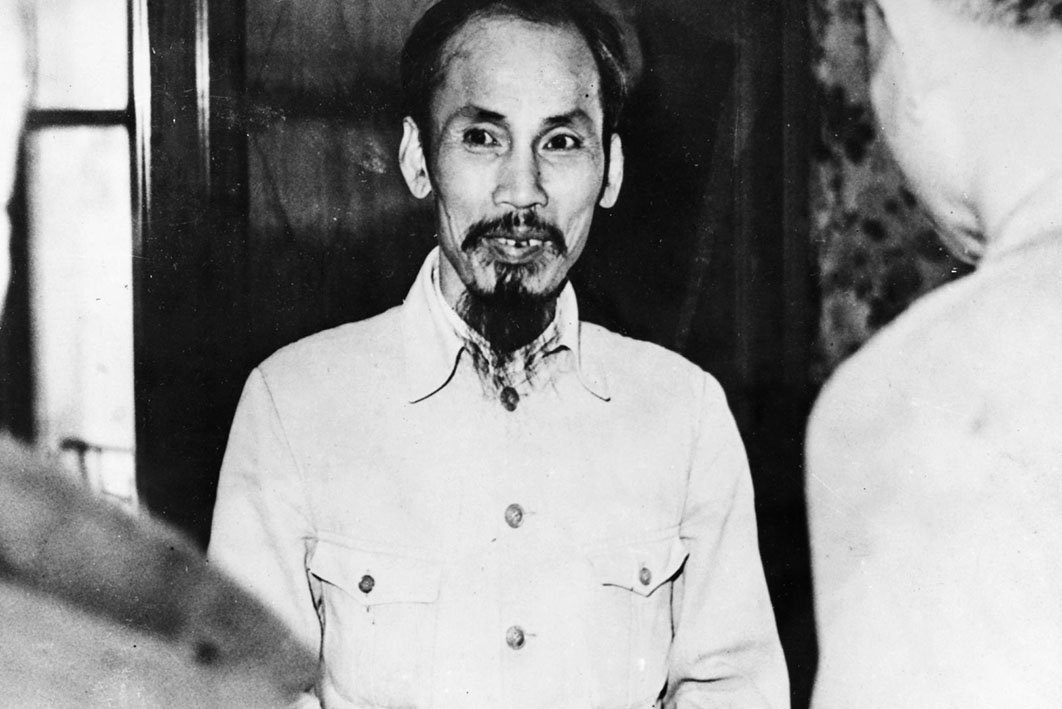

Australian poet and political activist Aileen Palmer’s translation of Ho Chi Minh’s prison diary — 115 poems written during those two wartime years — was commissioned by the Foreign Languages Publishing House in Hanoi and published in 1962. It was republished in the United States in the early 1970s and reprinted many times over the next two decades. Uncle Ho, as he is known to Vietnamese people, was committed to an independent Vietnam free of its French colonisers. He wrote the poems when he was a prisoner of Chiang Kai-shek’s police after having been picked up on suspicion of espionage, though he was actually on his way from Indochina to confer with Chiang about forming a common front against the Japanese. The verses trace his journey as he is marched from jail to jail in South China, often in leg irons, over more than a year.

Behrouz Boochani overcame what seem like insurmountable difficulties to get his writing out of the prison on Manus, using a smuggled mobile phone while always under threat of surveillance. Ho Chi Minh could be more open: he wrote his prison diary in a notebook using Chinese calligraphy so as not to raise suspicion among his Chinese guards by writing in Vietnamese or French, languages they did not understand.

Palmer’s publishers provided her with a literal, word-for-word translation of the Chinese into English and asked her to provide a poetic rendering of the quatrains and Tang poems. An accomplished linguist, she had published translations of poems from French, German, Spanish and Russian, but was uncomfortable about being presented as the work’s “translator” since, she said, she was not familiar with the “music” of the original language.

Ho’s concise nuggets of verse depict the daily struggles of prison life. But poetry for him, as for Boochani, also offered a form of transcendence. In “Moonlight,” he finds comfort in glimpses of the natural world:

For prisoners, there is no alcohol nor flowers,

But the night is so lovely, how can we celebrate it?

I go to the air-hole and stare up at the moon,

And through the air-hole the moon smiles at the poet.

Boochani writes of the Manusian full moon as “practising colour-blending… like a watercolour painting”:

An assembly of sorcerous colours /

Yellow, orange and red /

Talismans… /

Offerings… /

Gifts from each night.

Thematically, Boochani’s and Ho’s poems are in many ways similar despite their different settings and styles. They cover not only the daily privations of prison life but also the despair at not knowing when it will end, the wasting of time that cannot be recovered and, above all, the injustice of their imprisonment. Ho asks:

What crime have I committed, I keep on asking?

The crime of being devoted to my people.

Boochani’s title refers to the vast mountains of his native Kurdistan, and he thrusts back into his past to counter the horror of the nights on Manus: “Where have I come from? From the land of rivers, the land of waterfalls, the land of ancient chants, the land of mountains… Do the Kurds have any friends other than the mountains?”

Earlier, in a delirious sleep on the deck of the pitching boat from Indonesia, he escaped to those mountains of his homeland:

Grand mountain peaks covered with snow, full of ice, abounding in cold /

I am there /

I am an eagle /

I am flying over the mountainous terrain /

Over mountains covering mountains /

There is no ocean in sight /

In “Autumn Night,” Ho also travels to his homeland in his imagination:

In front of the gate, the guard stands with his rifle.

Above, untidy clouds are carrying away the moon.

The bed-bugs are swarming around like army tanks on manoeuvres,

While the mosquitoes form squadrons, attacking like fighter-planes.

My heart travels a thousand li toward my native land.

My dream intertwines with sadness like a skein of a thousand threads.

Innocent, I have now endured a whole year in prison.

Using my tears for ink, I turn my thoughts into verses.

Aileen Palmer’s mother, Nettie Palmer, had published two small volumes of published verse before turning to journalism during the first world war. She made the shift partly to help support her family but also out of a feeling that the world was too awful a place for writing poetry. Aileen, on the other hand, always saw herself as a “poet of conscience,” and her belief in the power of language and poetry to bring about change helped her reconcile her work as a political activist with her desire to write. As she wrote in an unpublished poem:

Words are small worlds, balloons to travel in outer-space, or just between

your ignorance and mine; to unravel this latent strength we hold, unseen…

She published poems about García Lorca and other Spanish civil war poets, and about nuclear testing on Maralinga; she translated the political poems of Louis Aragon and Nicolas Guillen. She also wrote of the educated political prisoners in the French prisons in Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) who taught illiterate peasants to read and write. Her powerful poem “Lines Painted on the Wall of a Death-Cell,” published in her 1964 collection World Without Strangers?, finishes with:

Unlettered are my people, bound

Like buffaloes to an empire’s yoke,

But, though men lay me deep in ground,

Perhaps you’ll know at last I spoke.

In another country in another time, Behrouz Boochani discovered lines of Persian poetry, written by previous detainees, on the walls of the tiny room he was to share with three other refugees on Manus Island.

Ho Chi Minh was around fifty when he was imprisoned in 1942. Behrouz Boochani turned thirty on Christmas Island in July 2013, the month the Rudd government announced it would reinforce Australia’s borders by turning back asylum seekers arriving by boat. Those who were already detained were transferred to detention centres on Nauru and Manus Island, and a thousand of them are still detained indefinitely. Boochani has received literary awards for No Friend but the Mountains, has published articles in newspapers and journals, and has co-directed a film and collaborated on a play during nearly six years of incarceration.

Boochani’s narrative ends on a note of despair with the killing of his friend Reza Barati, “the Gentle Giant,” in 2014. But in a statement at the end of the essay that completes the book, he writes, “We need to continue resisting, we need respect to become stronger and fiercer. This will take time, but I’ll continue challenging the system and I will win in the end.”

Ho Chi Minh became president of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in 1945 and died in 1969, a revered figure in the country he liberated from colonial rule. In “Word-Play II,” one of the poems in Prison Diaries, he writes:

People who come out of prison can build up the country.

Misfortune is a test of people’s fidelity.

Those who protest at injustice are people of true merit.

When the prison-doors are opened, the real dragon will fly out. •