Last week’s Victorian audit office report on Melbourne’s controversial East West Link project leaves few involved in the project unburned. In a searing appraisal, the state Coalition, the Labor Party, the public service and even the private consortium contracted to build the link are found to have been negligent and imprudent, and to have taken unacceptable risks with taxpayer dollars or told less than the whole truth. “From its inception to its termination,” auditor-general Peter Frost writes, “the EWL project was not managed effectively.” In fact, the whole process was so flawed that “it will become an important marker in the history of public administration in this state.”

Have we learned anything from this? Listening to the state treasurer, Tim Pallas, and his opposite number, Michael O’Brien, trading blows last week, it was hard to believe we have. Both deny responsibility and point the finger at the other, cherrypicking findings and vying to appear the most outraged. More surprising, however, is the battle over the role of the public service in this billion-dollar fiasco. Behind all the bluster is a serious debate, not just about the quality of officials’ advice about the project but also about their role in our system of government.

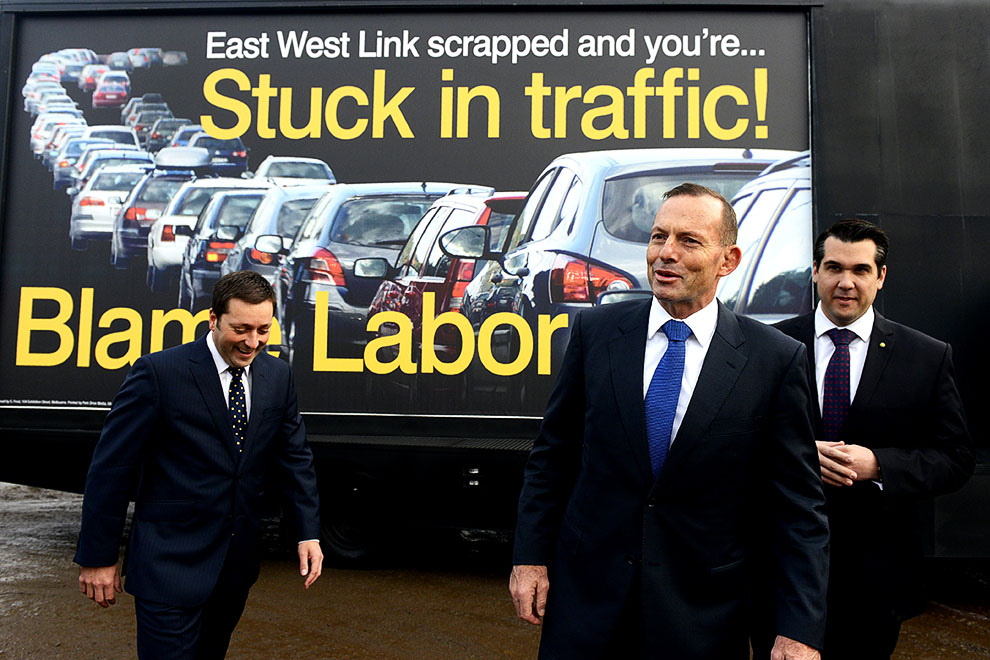

Touted as the missing link in Melbourne’s freeway network, East West Link would tunnel under the city’s latte-sipping inner north to connect the Eastern Freeway with CityLink, then continue to the Western Ring Road. The Baillieu government adopted the link as its signature project in 2011 and just two months before the 2014 state election Baillieu’s successor, Denis Napthine, signed contracts with the East West Connect consortium to build the link – despite a pending court challenge and Labor’s commitment to can the project. On winning the election, Daniel Andrews’s Labor government did just that, paying out $643 million (and counting) in compensation. Add to that all the money spent by the Coalition on the project – give or take how many acquired properties can be resold – and that’s a fiasco well worth an independent audit.

While the auditor-general finds the Coalition and Labor governments guilty of ignoring advice, rushing processes and taking huge risks with state funds – findings echoed this week in a review of the Abbott government’s funding of the project – the real focus is on the state bureaucracy and its role in all this. “Over the life of this costly and complex project, advice to government did not always meet the expected standard of being frank and fearless,” he writes.

At every stage, the bureaucracy gave “too much emphasis to the benefits of approaches that were in line with the government’s preferred outcome and little emphasis to alternative options that could be argued were more aligned with the state’s best interests.” Some officials admitted they thought giving advice that went against what the government wanted to hear could jeopardise their careers and influence. More than that, it would be plainly naive.

The auditor-general fears this attitude poses a serious threat to the integrity of the service:

It is not sufficient for public servants to avoid providing advice or recommendations simply because they believe the government of the day does not want to hear them. Doing so is at odds with the Public Administration Act 2004 and the Code of Conduct for Victorian Public Sector Employees, which require the public service to act impartially and achieve the best use of resources.

The state bureaucracy vigorously denies this interpretation of the debacle and has rejected the audit entirely. In fact, Chris Eccles, secretary of the Department of Premier and Cabinet, argues the audit mistakes the role of the bureaucracy:

Since the earliest articulation of a professional, apolitical public service in the 1850s, the role of the public service has been to serve, and act as an instrument of, the government of the day… For a public servant to hinder progress to implement a lawful decision, constantly recontest that decision, or refrain from actions that follow from a lawful decision of a minister, would be to fundamentally undermine the Victorian Public Service as a trusted and apolitical institution, undermine the integrity of our democracy, and erode longstanding conventions that are at the heart of the Westminster system of government.

In other words, the public service has to do what it is told. We can’t have Sir Humphreys white-anting ministers and their policies. If the government’s preferences are understood and explicit, bureaucrats have an obligation to go with them. They can’t repeatedly “recommend courses of action that are contrary to the government’s settled policy” – that would subvert democracy.

The auditor-general is unimpressed by this line of argument. He argues that the public service can’t cater its advice to suit the preferences and biases of the government of the day. When advising on a decision, it has to make recommendations based on what the evidence shows is in the best interests of the state. “At critical points in this project,” the auditor-general writes, “this did not occur.” That is to say there weren’t enough public servants saying things like, “Minister, with respect, I would advise against that” during the whole fiasco. Instead they were taking hints and working to them, at least according to this report.

So is the public service’s role first and foremost to turn the government’s every wish into reality? Or do we want a more independent, feisty service, one that says, “No, Minister”? Would that jeopardise democracy, or is that a necessary check on the whims and petty interests of governments?

These are big questions. How they’re handled is not a merely abstract issue. In the case of East West Link, the public service’s advice could have been a key reason Victorians lost a billion dollars down the drain. Indeed, it could cost us a whole lot more yet. We may have a new infrastructure authority vetting projects, but the board includes the same officials who worked on East West Link. The same people, the same departments, the same overall system are handling the $11 billion Melbourne Metro and the $5.5 billion Western Distributor. What reason is there to expect these won’t fall victim to the same pitfalls as plagued East West Link? None of the auditor-general’s recommendations have been accepted by anyone; if the report is right, that means none of the lessons have been learned.

As the blame game whirs on, the question remains: how did Victoria get itself into this mess? Was this a one-off fumble? Or are there deeper cultural and structural problems in our government, problems that threaten to derail future projects? What really went wrong with East West Link? That’s still the billion-dollar question. •