Nettie Palmer’s break came with an article, “How the War Affects Christmas in London,” one of her first pieces for the mainstream press. It was feted across Australia in 1915, her words resonating with the public’s war-weariness. By July 1916 she had a weekly column, “Readers and Writers,” in the Melbourne Argus. Her spirited and provocative essays grounded contemporary tragedies of war and revolution not in sentiment but in compassion. “Too high and mighty,” her uncle Henry Bournes Higgins, the High Court judge, counselled. The column lasted for only nineteen articles before her second daughter was born in September 1917.

Palmer’s key strength, and the reason she was so loved by her readers, was an ability to listen for the future in her fine critical writing. She relied on the early modernist impulse to strip to the essence and find hope, inviting her readers to think about how to take responsibility for the issues under discussion.

She wrote about the profound and the seemingly trivial, the newsworthy and the ancient, from Indigenous languages to comics, from Thomas Hardy to C.J. Dennis, and from Rebecca West to Katharine Susannah Prichard. Palmer’s significance in Australian letters has been framed by academics who emphasise her importance as a shaper of Australian literature and its canon, but she was a writer who also worked as a freelance journalist with an extremely broad range.

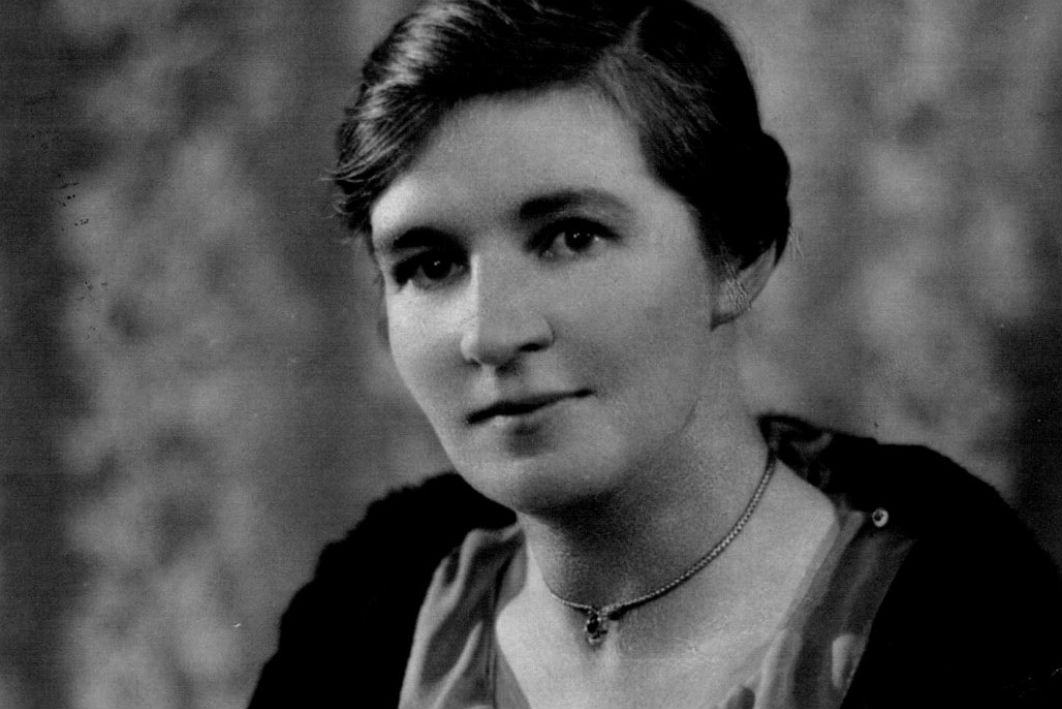

Janet Gertrude Higgins, born in 1885 and educated at the advanced Presbyterian Ladies’ College, was of the second generation of women in her family to attend the University of Melbourne — even before white women, let alone Indigenous women, had the vote. She was reared with high expectations of economic independence, steeped in Victoria’s colonial liberalism and feminism.

She wrote her first book as a child: The Story of My Life, Mingled with Others. While completing a Master of Arts in classics, she was influenced by the poet Bernard O’Dowd’s vision of an Australia transforming the sins of the old world. In 1910 she completed an International Diploma of Phonetics in Berlin, London and Paris, and then taught modern languages at her former school and wrote for the socialist press. In 1914 she married Vance Palmer, fellow writer and journalist, in London. With militarism stalking journalism and the labour press nearing collapse, they were forced to return to Victoria in 1915.

For nearly a decade living in the Dandenongs, east of Melbourne, Palmer edited the poetry magazine Birth, then wrote for the Herald, Stead’s Review, Spinner and the Bulletin. When the Palmers moved to Queensland, and with her daughters at school, Palmer got into her stride. From 1925 to 1935 she wrote three to four 1500-word articles each week — including a weekly column for the Illustrated Tasmanian News, often weekly pieces for the Courier and the Telegraph and unsigned Saturday leaders. She wrote regularly for the Bulletin’s Red Page, the Daily Mail and the Sunday Mail, and occasionally for the Argus, the Sydney Morning Herald, the Age, the London Times and the West Australian. She also wrote for many of the new commercial periodicals, including contributing a column to All About Books, and for the women’s press, most frequently for the Australian Woman’s Mirror.

The Bulletin editor thought hers was the best critical work he published. Firmin McKinnon, the editor of the Courier, asserted that he printed anything she wrote without looking at it. And she made use of her considerable freedom. Postcolonial in the broadest sense, and long before A.A. Phillips framed our “cultural cringe,” she challenged her “colonial provincial” readers about Australian philistinism and allegiance to anything British. She and her family had returned to Melbourne in late 1929.

A 1934 Argus series on the Dandenongs was published in book form. Regional writings on Green Island, the Sunshine Coast and parts of Victoria were a powerful strand of her work. Most of Palmer’s books originated in her journalism; Talking It Over was a selection of essays that were first published in various newspapers. Palmer also took on commissioned work. Her political biography of Henry Bournes Higgins was reviewed across the globe. Her editing of The Centenary Gift Book for Victoria’s centenary included a wonderfully inclusive, rigorous selection of Victorian women’s voices from across the political and class spectrum.

In 1936, caught up in the Spanish conflagration, Palmer published first-hand accounts for the Argus, then returned to Melbourne and wrote for and edited three booklets on the Spanish civil war, warning of the coming dangers. She was the Melbourne editor for Woman Today, had a column for the New Zealand journal Tomorrow, and she was involved increasingly in speaking out against fascism. During this period she also taught English to European refugees.

The later years of her life saw the consolidation of her journalism on Henry Handel Richardson into the first book-length study, and a co-authored biography of Bernard O’Dowd. In 1948 she wrote Fourteen Years: Extracts from a Private Journal 1925–1939, a story of a life among many of the foremost contemporary writers, artists and journalists, both national and international.

Through her ABC radio broadcasting, lecturing for the Commonwealth Literary Fund, and support for Australian writers and for literary journals such as Meanjin, she was a self-professed “public relations office” who saw her task as needing to “watch and listen effectively,” especially at the intersection of foreign languages and literature.

Palmer’s early analysis of housework was an important precursor to the women’s liberation movement, and many of the progressive values she espoused on the environment, multiculturalism and aesthetics sowed seeds for the future. “You are a wise — a very wise woman,” Henry Handel Richardson had told her. “Few have your critical ability.” For four decades, she and her husband were forerunners, preparing the ground for the cultural and social awakening of the 1970s and the halcyon days of publishing in Australia. ●

Nettie Palmer was this week inducted into the Melbourne Press Club’s Australian Media Hall of Fame. This is the text of Deborah Jordan’s profile accompanying the citation.