If you like elections, feel free to feast. We’ve had the appetisers, with the Eden-Monaro by-election in July and the Northern Territory vote in August. On 17 October, New Zealand will go to the polls, and so does the Australian Capital Territory.

Two weeks later, it will be Queensland’s turn — then, on Melbourne Cup day, some country on the other side of the world is having some sort of election that could be interesting.

So far Labor has won two out of two — and there is a chance that the left will win all six. Jacinda Ardern’s Labour government is well ahead in the polls across the Tasman. Former vice-president Joe Biden seems to have almost wrapped up the race for the White House. Queensland is looking more problematic for the Palaszczuk government, although arguably no more so than three months from the 2017 election, which it won.

The ACT is a category of its own. First, chief minister Andrew Barr runs the only Labor–Greens coalition government in Australia. Unlike Tasmania’s Labor–Greens coalitions, it has been harmonious, so far lasting twelve years without any serious public blow-up. If Labor and the Greens are ever to form a coalition at the federal level — and the voters may give them no choice — this is the model they would have to follow.

Second, the ACT has the only government on the mainland elected by proportional representation. Since self-government was imposed on the territory by the Hawke government in 1989, only once in nine elections has one party won a majority. Minority government is normal here, and after a chaotic start, it’s settled into a very stable system.

Third, ACT politics is so stable that this government — first as Labor, then as Labor–Greens — has ruled uninterrupted since 2001. If it wins on 17 October, it will be the first government in Australia since Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s to rule for more than twenty years. The Liberals dominated territory politics in the first twelve years, but since 2001 they have lost every election.

Fourth, there is little interest in this one. Until this week, there was only one published poll, taken six weeks ago by uComms for the Australian Institute; its numbers suggested the government is heading for re-election, with the Greens gaining ground. A lobby group at odds with the government, Clubs ACT, has just come up with its own online survey, which depicts a closer race, although not the landslide the Liberals would need to win.

For comparison: the bookies’ odds put the outcome in Queensland as roughly 50–50 between Labor and the Liberal National Party; they give Joe Biden a 58 per cent chance of winning the US election, Jacinda Ardern a 92 per cent chance of being re-elected in New Zealand — and Labor and the Greens a 75 per cent chance of winning a sixth term in the ACT.

Yet all the pre-election commentary in the local media assumes that the Liberals have a real chance of winning this one. After all, they won eleven of the twenty-five seats last time; so they need to gain just two seats to form government. In one electorate they’ve had a very helpful redistribution. They must have a chance.

Yes, they do — but not on their own. There is only one seat they could realistically hope to gain. They would need a right-leaning independent to take another seat off Labor or the Greens to make a change of government possible. But the bookies are right: it is only an outside chance. Let’s find out why.

John Howard used to complain that Canberra “looks like Killara and votes like Cessnock.” With the arguable exception of Darwin, it is the richest city in Australia, and by some way. The 2016 census reported the median weekly household income as $2043, well ahead of Sydney ($1750) and Melbourne ($1542). It’s also Australia’s best-educated city, and two-income families have long been the norm. Yet it’s safe Labor — or, these days, Labor–Greens.

Stephen Barber of the Federal Parliamentary Library estimates that in two-party terms, Labor has outpolled the Liberals in the ACT at twenty of the last twenty-one federal elections; the exception was 1975, and then only just. The public service now accounts for only a third of the ACT’s employment, but Canberra has an ethos oriented to increasing public welfare whereas the Liberals’ ethos is oriented to increasing private opportunity.

But that hasn’t always blocked them in local politics. Canberra was Liberal territory for most of the 1990s, under Kate Carnell, now the federal government’s small business ombudsman. She was the kind of modern, stylish, centrist Liberal that Canberra voters liked, and she won two elections to prove it. But her leadership crumbled after a terrible tragedy — the death of a girl from the implosion of the old Royal Canberra Hospital, staged as a public event — and massive cost overruns in redeveloping Bruce Stadium for the 2000 Olympics.

The 2001 election brought Labor to power with Greens support, and they have been there ever since. As in Victoria, the ACT Liberal Party has moved to the right in opposition; its dominant figure is Senator Zed Seselja, federal assistant finance minister and conservative flagbearer, and leading moderates have been driven out of the party. Its message to the voters focuses on tax cuts and, at this election, showbags of unfunded spending.

As Liberal leader at the 2012 election, Seselja came closest to getting the party back into government, winning eight of what were then seventeen seats in the Assembly. But it came nowhere near winning the ninth. Seselja fought that election on a shabbily dishonest campaign against Labor’s reforms — now supported by many federal and interstate Liberals — to phase out stamp duty on house purchases and replace it with higher rates and land tax.

For the 2016 election, the ACT Assembly was expanded to twenty-five members, with five electorates choosing five members each. The main issue was Labor’s expensive new tramline from the city centre to outer-northern Gungahlin. In a city designed for cars, the tram was visionary rather than viable; it will end up costing ACT residents an average of $5000 per household to build and operate, though relatively few will use it. But the public sided with the visionaries: Labor won twelve seats and the Greens two, against the Liberals’ eleven.

This time there is no big issue. Labor and the Greens are planning a second tramline to the south; that’s Liberal turf, so this time the opposition is doing its best to ignore it. While former Labor chief minister Jon Stanhope is hammering Barr’s government, alleging lax fiscal management and poor spending priorities (at the cost of health and welfare needs), those issues haven’t reverberated. Indeed, the Liberals’ policies revealed so far would only make the fiscal problems worse.

Coronavirus is not an issue here, except as a plus for the government. There has been no new case of the virus for almost three months. There has been just one unsolved case of community transmission, back in April. The restrictions and social distancing have been managed relatively pragmatically. In itself, the ACT’s handling of the virus suggests a sensible, competent government rather than one that needs changing.

Nor is the economy an electoral liability. The ACT was the only place in Australia where demand grew in the first half of 2020 — thanks to the dominant role government plays in its economy, true, but private spending also held up better than anywhere else. The August jobs figures showed hours worked jumped 5.3 per cent year-on-year in the ACT, while falling by the same percentage in the rest of Australia.

But not all issues have been handled so well: planning, transport priorities, health spending, and the slow deterioration of community infrastructure are all liabilities for Labor. It’s been in office a long time, and it shows.

Forty-seven-year-old Andrew Barr has led Labor since Katy Gallagher abandoned ship in 2014 to enter federal politics. The first openly gay leader of any Australian government, he is otherwise a fairly conventional member of the Labor right who has spent almost his entire adult life in ACT politics. At his best, he exudes a gentle competence that makes him seem a safe pair of hands. But he has been criticised on fronts ranging from favouring certain developers to failing to do enough to tackle poverty or fund hospitals — or to protect the ACT’s budget.

His opponent, thirty-six-year-old Alistair Coe, didn’t even wait for adult life to get into politics. He joined the Liberal Party while still a schoolboy at Radford College. At twenty-one he was on the Liberal Party’s federal executive, and at twenty-four he had already jumped from staffer to being an MLA. He is a Seselja conservative: if Barr is best-known nationally for being an openly gay leader, Coe is known for being the one Liberal leader in the nation to vote “no” in the referendum on gay marriage.

Canberrans also know him for the grin seemingly fixed permanently on his face, no matter how serious the subject; at times it does create an impression of insincerity. His repeated refusal to explain how the Liberals would simultaneously cut taxes and finance dozens of spending promises, some quite hefty, has echoes of Tony Abbott in 2013. The Liberals in office would not be able to meet all the promises they are making.

The ACT’s five-member electorates appeal to the major parties because they are sure to win at least two seats each; the real contest is for the fifth seat. At least it’s always been that way in Canberra. It only takes 33.3 per cent of the vote to win two of the five, not a high bar for a big party to hurdle.

Canberra is divided into six distinct districts, and every district has its own electorate (with the inner north and inner south sharing one). Last time, Labor won the fifth seat in outer-northern Yerrabi (the new district of Gungahlin) and middle-northern Ginninderra (Belconnen). The Greens won it in inner-suburban Kurrajong and the middle-southern Murrumbidgee (Woden/Weston Creek). And the Liberals won the final seat in outer-southern Brindabella (Tuggeranong).

In Yerrabi and Kurrajong, those results were clear-cut. The other three were close: the Liberals won the final seat in Brindabella by 1.2 per cent over Labor, which in turn won the final seat in Ginninderra by 1.5 per cent over the Greens, who in turn won the final seat in Murrumbidgee by 1.6 per cent over the Liberals. Each of the three parties won one close contest and lost another.

Since then a redistribution has moved the affluent inner-southern suburbs of Deakin and Yarralumla from Kurrajong into Murrumbidgee — from which Greens MLA Caroline Le Couteur is also retiring. Two Labor booths have been shifted from Murrumbidgee into Brindabella. All of that makes the last seat in Murrumbidgee very borderline; it’s the one the Liberals have a good chance of picking up. But they’re not the only contender with a chance — some old hands say community leader Fiona Carrick, running as an independent, could win the seat instead.

While some previews suggested the Liberals could win a third seat in Yerrabi, in the real world that requires a landslide swing of 5.5 per cent: no way, José. They are even less likely to win a third seat in Ginninderra — their best chance there is that their veteran one-time leader Bill Stefaniak might win it from Labor for his Belco (Belconnen) party, then give them his support.

The Liberals could also struggle to hold their ground in Kurrajong and Brindabella. Let’s go back to that uComms poll — and remember, a similar poll the same pollster took six weeks before the Northern Territory election proved to be uncannily accurate.

For the ACT, uComms reported that Labor’s vote was down 0.8 per cent, the Liberals up 1.5 per cent, the Greens up 4.3 per cent, and “others” down 5 per cent. Net out the impact of losing others’ preferences and, in three-party terms, Labor was down about 2 per cent, the Liberals flat, fewer “others” votes ran out of preferences — and the Greens’ vote rose 3.4 per cent.

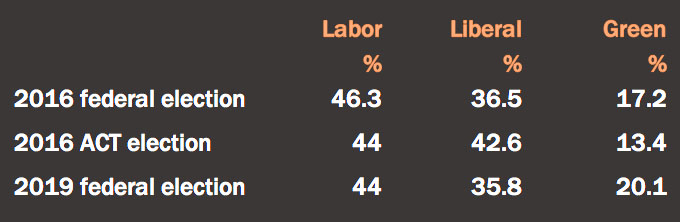

Now take a look at what the ACT voters did last time they voted — at last year’s federal election. Sure, federal and state/territory elections are different, and the ACT Liberals usually poll better in the local elections than federal ones. But after the smaller parties were counted out, the difference in the three-party votes is stunning:

Sources: Federal election results from the Australian Electoral Commission; 2016 ACT election figures are the author’s estimates

The shift between the two federal elections mirrors the shift reported by uComms. And on these figures, there is scope for a big rise in the Greens vote on 17 October — and little scope for a big rise in the Liberal vote.

The Greens can always be their own worst enemy. One reason their vote was so low in 2016 was that every one of their five lead candidates lived in the inner north: that cost them badly in Tuggeranong and Gungahlin. Their big policy for this election is to propose banning gas connections to new Canberra homes: another policy designed to inspire their eco-warriors and turn off voters. Barr promptly ruled it out.

If the Greens could repeat their 2019 vote, however, that would transform the Assembly. On my estimates, a repeat would see them take the final seats in Yerrabi and Ginninderra from Labor, take the final seat in Brindabella from the Liberals, hold their seat in Murrumbidgee, and outpoll the Liberals in Kurrajong, leaving the Liberals with only one seat there. If all that happened — and it was the way ACT residents voted last year — the new Assembly would have ten Labor, nine Liberals and six Greens.

That’s not likely to happen. But last year’s vote and the uComms poll suggest that’s the direction in which the ACT electorate is moving. There’s a certain weariness with this government, but none of the groundswell you usually sense when governments are about to change. The last time the Liberals won here was in 1998, and they were a different party then. •