Generations of psychiatrists, psychologists and brain scientists can remember being turned on to the fascinations of mind and brain by the Anglo-American neurologist Oliver Sacks. In a long succession of popular books that began appearing in the early 1970s he explored topics as varied as migraine, deafness, autism, Tourette’s and colour-blindness, often through the medium of case studies. Readers learned of chronically catatonic patients reanimated by a miracle drug, people with remarkable talents, men who mistook their wives for hats. A kind of David Attenborough of the brain, Sacks revealed the wonders inside our skulls without resorting to superficial gee-whizzardry.

Sacks’s appeal rested on his sensibility as much as his absorbing choice of topics. His books radiate empathic involvement in clinical cases, scepticism of received wisdom, a keenness to see strengths where others see pathologies, and a deep curiosity. They also link the particularities of each case to the big ideas of philosophers, novelists and poets. Sacks offered a way for people with literary and humanistic interests to feel that the maladies of the brain belonged to them as much as to doctors and scientists.

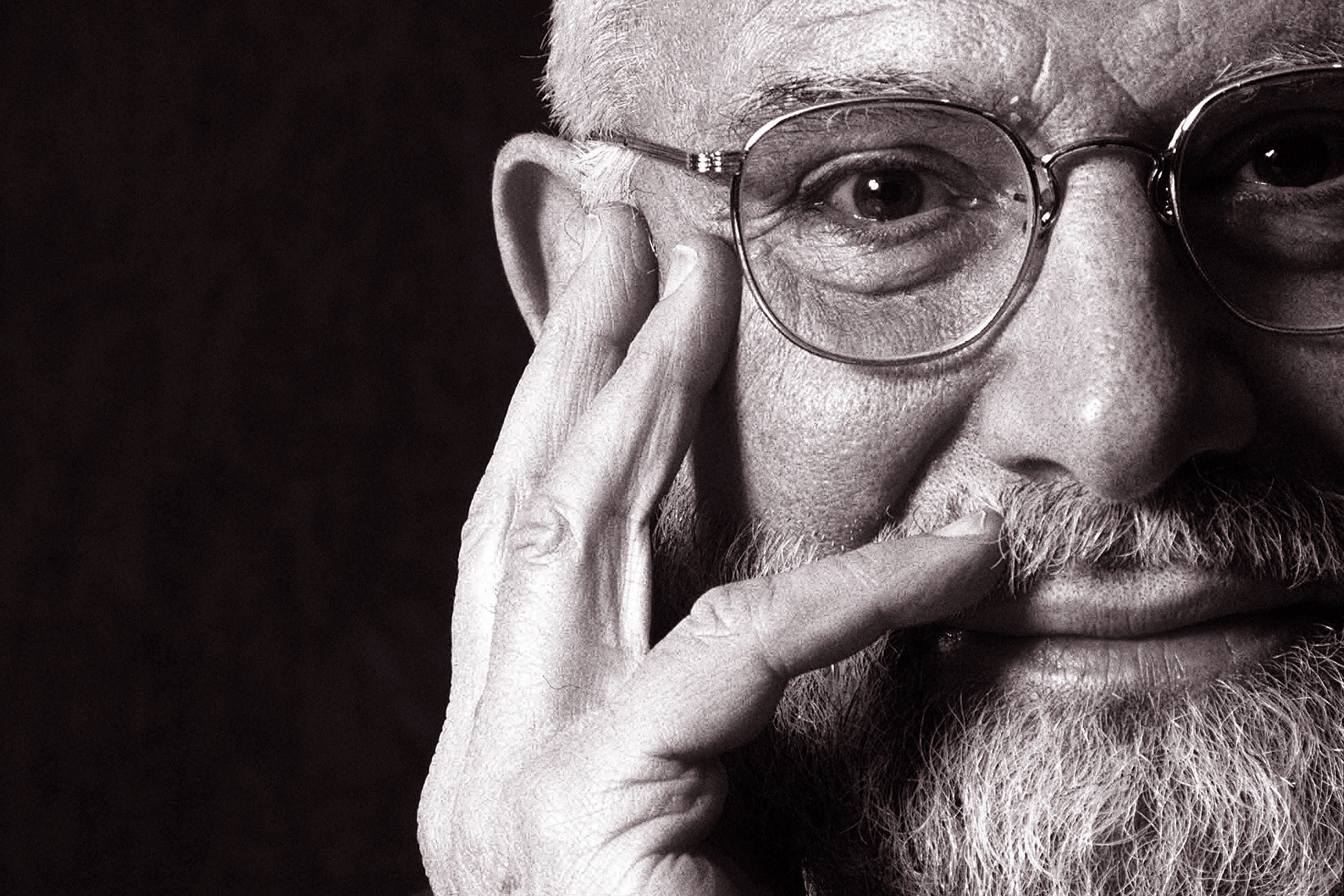

What the average reader made of Sacks the man is less obvious. In Awakenings (1990), Robin Williams played him as diffident and bookish but compassionate. On book jackets he appeared luxuriantly bearded and smiling. Sacks revealed more of himself in Uncle Tungsten, a memoir of his precocious scientific interests as a child, and in On the Move, an autobiography published in 2015, the year he died. But nothing exposes Sacks as much as his letters, now selected and edited by his long-term assistant, editor and friend, Kate Edgar.

The magnitude of Edgar’s curatorial task is staggering. Sacks didn’t so much write letters as extrude them. His output amounted to around 200,000 pages, on top of journals that sometimes, he claimed, accumulated a million words each year. In one missive he diagnoses himself with “incontinently volcanic logorrhea.”

Edgar has done a masterful job of extracting and organising several hundred of the letters, written between the ages of twenty-seven, soon after the young Dr Sacks moved from London to San Francisco, and eighty-two, and placing them in the context of his life. Striking in many ways, they address family members, friends and a host of noted writers in neuroscience and medicine as well as in the transatlantic literary world. Correspondents include W.H. Auden, Francis Crick, Daniel Dennett, Jane Goodall, Steven J. Gould, Harold Pinter, Peter Singer, Susan Sontag and Paul Theroux, as well as a diverse collection of admirers.

As pieces of writing, the letters are generally long and meandering. Sacks often apologises for rambling on but then proceeds to “babble” some more. There is nothing formulaic here, though: some expressions and ideas are inevitably repeated, but Sacks addresses each correspondent with directness and authenticity. He typically begins with enthusiastic greetings and compliments before settling into an extended exposition of his current thinking and reading. It is a rare letter that doesn’t name-check other writers and recommend their works.

Sacks’s correspondence contains a disarming combination of intimacy and self-display. He takes pleasure in connection, but also in having a platform for self-exploration — a tendency he recognises, observing that “I am not a good correspondent because I write at people rather than to them.”

The Sacks that shines through the pages of Letters is no effete intellectual or bandy-legged nerd. In his twenties he is a champion power-lifter and in later years he swims, climbs mountains (breaking the leg that is the focus of his book A Leg to Stand On) and visits remote South Pacific islands. He consumes a frightening range and quantity of drugs well into midlife, rides and falls off motorbikes, and engages in assorted picaresque adventures. His aliveness to sensation and bodily experience dovetails with his clinical interest in hallucinations, phantom limbs, hearing loss, face-blindness and other perceptual phenomena.

Despite living a rather monastic life, often short of money, Sacks is no egoless monk, despite dubbing himself “the Spinoza of 78th St” after moving to New York City. From his twenties through his forties, he is fixated on professional success and recognition, agonising as expats are wont to do about whether and when to return home (as prodigal son or “beaten dog”), feeling ambivalent about the United States (an “awful cross between a kindergarten and a concentration camp”) and hatching extravagant plans for books and papers that never eventuate. He repeatedly tangles with bosses: he is hauled over the coals by his residency director for stealing hospital supplies (milk from the ward refrigerator) and fired from two hospital positions.

Although his superiors may well have been envious and unethical, as Edgar suggests, it is also easy to imagine that Sacks could be an arrogant handful. (In one letter he declares himself to be “a sort of genius.”) Some letters suggest a lack of humility and a sense of being exempt from ordinary social norms, a tendency perhaps exacerbated by being a physically imposing foreigner. It is impossible to say how much his sharp edges represent a prolonged adolescence, as Edgar suggests, or an enduring personality style or even a mild form of manic depression. Sacks was prone to worry that in addition to his “lethal neurosis” he might also be vulnerable to the psychosis that afflicted his brother Michael.

Sacks makes no secrets of his emotional turmoil, especially as a younger man. He ascribes some of his fears of abandonment to having been sent away from his family in 1939, aged six, to escape German bombing raids and he sometimes appears not to have forgiven his parents for allowing that to happen.

The perceived slights of friends and colleagues bruise him and he procrastinates terribly with his books: there is always more material to add. He is devastated by a review of his Leg book, which accuses him, among other things, of “medical egomania” and “intellectual messianism,” charges that may be excessively harsh but point to the hauteur that some critics saw in Sacks’s work and style. His letters reveal a gradual decline in this brittleness and agitation with age, which he attributes in large measure to Leonard Shengold, the psychoanalyst he consulted for almost fifty years.

Remaining single for most of his adult life after a brief but stormy love affair in his early thirties, Sacks seems to have retreated into self-reliance. “I am all-or-none,” he writes in a blistering farewell letter to his lover, “an attenuated relationship is worse than no relationship.” He only finds a stable partner in his sunset years, his autobiography publicly outing him as gay when he only has weeks to live. But these letters point to many intense and lasting friendships, including initially hero-worshipping connections to older men such as Auden and the pioneering Russian neurologist Alexander Luria, and more ambivalent relationships with men of his own vintage. Friendships with women seem relatively scarce.

Sacks’s remarkable appetite for letter-writing and his enthusiasm for clinical work evidently satisfied most of his desires for human contact. His letters furnish many examples of his generosity in reaching out or responding to young people, fledgling authors, and people and their carers with personal experience of neurological conditions. He received a great deal of praise from the public but gave a great deal back.

The letters do a particularly fine job of explaining why Sacks is such a distinctive writer. He is revealed as a prodigious reader of literature, philosophy, history and a range of sciences, from palaeontology to botany, giving him unparalleled breadth. He is also a fierce advocate for a narrative approach to medicine, elaborating the classic case study method, with its dry recitation of symptom and course, into an extended exploration of human individuality. His writing seeks to imagine and convey the world of the patient not only as it is affected by neurological disturbance but also as an “altered life-situation.” The result, he tells his literary agent, is “a rather rare sort of Art-Science.”

Sacks’s aversion to scientism was almost visceral: he repeatedly attacks the use of standardised measures and sample statistics in clinical practice and research, mentioning Thomas Gradgrind of Dickens’s Hard Times — he of “Facts alone are wanted in life” — no fewer than five times. “I think there is something almost inhuman,” he writes, “about the mechanical intelligence which has taken over so much scientific and medical writing.” In similar fashion medical education is dismissed as “systematic idiocy” that “reduces everything to information and skills.”

Although his skilled story-telling gave his clinical tales a vividness and warmth that many lay readers find enchanting, it is not surprising that medical colleagues could find it immodest and showy. They may well have guessed his views on their own work, which he expressed pungently in a letter to his brother Marcus: “as for my fellow-neurologists, they can go to blazes (neurology has been dead, imaginatively, and fundamentally, for half a century anyhow).”

Sacks saw himself primarily as a describer of clinical phenomena, a gifted observer or “astronomer of the inward” rather than an explainer. His insistence on the uniqueness of the individual and his reliance on rich description resonate with our contemporary valuing of “lived experience” over scientific knowledge. In another way, though, his elevation of individuality is out of fashion. He expresses scepticism about diagnosis- or disability-based identities and claims to see gender as a meaningless category. In this respect, his compelling stories of unusual experience seem to omit important dimensions of social and political reality.

Oliver Sacks is no longer with us, but bright new Olivers and Olivias are sure to be emerging at the turbulent interface of science and art. How will future generations understand their lives of exploration, angst and accomplishment without hoards of letters? Half a century from now, will biographers assemble hundreds of emails and social media posts to create pointillist portraits of their subjects? There may still be memoirs and biographies in fifty years, but they will lack the unfolding, unguarded multiplicity of a Sacksian trove of letters, each one a time capsule of thoughts conjured up at a particular time and addressed to a particular person.

The technological obsolescence of the letter, and with it the gradual generational disappearance of letter-writers, is a profound loss for our capacity to understand the texture of people’s lives. As letter-writers gradually become extinct, we should be very grateful to Oliver Sacks for his compulsion to write and to Kate Edgar for her labour of love in assembling this wonderful collection. •

Letters

By Oliver Sacks | Edited by Kate Edgar | Picador | $39.99 | 736 pages