Leaping into Waterfalls: The Enigmatic Gillian Mears

By Bernadette Brennan | Allen & Unwin | $34.99 | 360 pages

From the age of ten, “nothing” mattered more to Gillian Mears than horseriding. The family had arrived in the northern NSW town of Grafton at the end of 1973, and Gillian soon had her own pony, Flicker, a bolter. She’d follow Yvonne — the eldest of the four Mears girls — galloping down “the old Arthur Street stock route,” jumping “over enormous ditches, picnic tables, gravestones and racetrack railings.” Adventure, risk and terror, an exhilaration felt throughout her body. She’d also ride with her friend Sandra Watkins, more galloping, then taking their ponies into the river and immersing themselves in the fast-flowing water. The freedom of it, and the risk.

The Clarence River ran behind the ferryman’s house where the Mears family lived, and as a child Gillian had wanted it to flood like the photos in the museum, with kangaroos sitting on the roof of the pub. Extremity, wildness, she wanted it all. And also a sanctuary from which to watch. She was a shy girl, watchful, taking everything in — and vulnerable as the dark pressed in on her.

Which it did. Nothing was easy with Yvonne, with love and submission, admiration and rivalry entangled from the start. And her mother was disappointed that she chose to ride when she had other talents — the flute for instance, couldn’t she give her time to that? The sisters’ “messiness and horsiness” saddened her, Gillian would later say, and the sanctuary of the mother evaporated, or seemed to, as Sheila Mears “retreated” from her daughters.

Hanging over everything Gillian went on to write would be the shadow of sibling jealousy and of the disappointed, troubled mother who would die of cancer, at fifty-five, in 1991. Gillian Mears was twenty-seven by then, and had already published two collections of short stories and a novel. Ride a Cock Horse (1988) had won the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for best first book (Southeast Asia and South Pacific Region). Sheila Mears lived to see her horsy daughter’s success as a writer, but not to see her stricken — as her own father had been — by the multiple sclerosis that made its dark appearance during Gillian’s thirties.

Death, the perils and fragility of life, its fleeting quality, had been with Gillian from an early age. Her childhood had ended a decade earlier, she would say, when her river-riding friend Sandra Watkins and her brother were shot in 1980 by their mother. A murder-suicide, another haunting that Gillian would write about obsessively in her diary and in her early stories. The dread that existed alongside exhilaration. How was she to live without succumbing to one and losing the other?

In her final year of school she determined on a path that would be subversive, embracing life in all its aspects, refusing society’s norms and rules. She would be herself, “ME myself… completely.” She then began an affair with her much older high school English teacher, and four years later would marry him. For a young woman determined against “lamb-chopdom,” the short-term sanctuary of marriage proved a long-term stifling as she found herself up against the conundrum of what that ME might be. That wild, mercurial self; those many selves wrapped up in the person of Gillian Mears. “One of the most important Australian female writers of the last forty years,” Bernadette Brennan calls her.

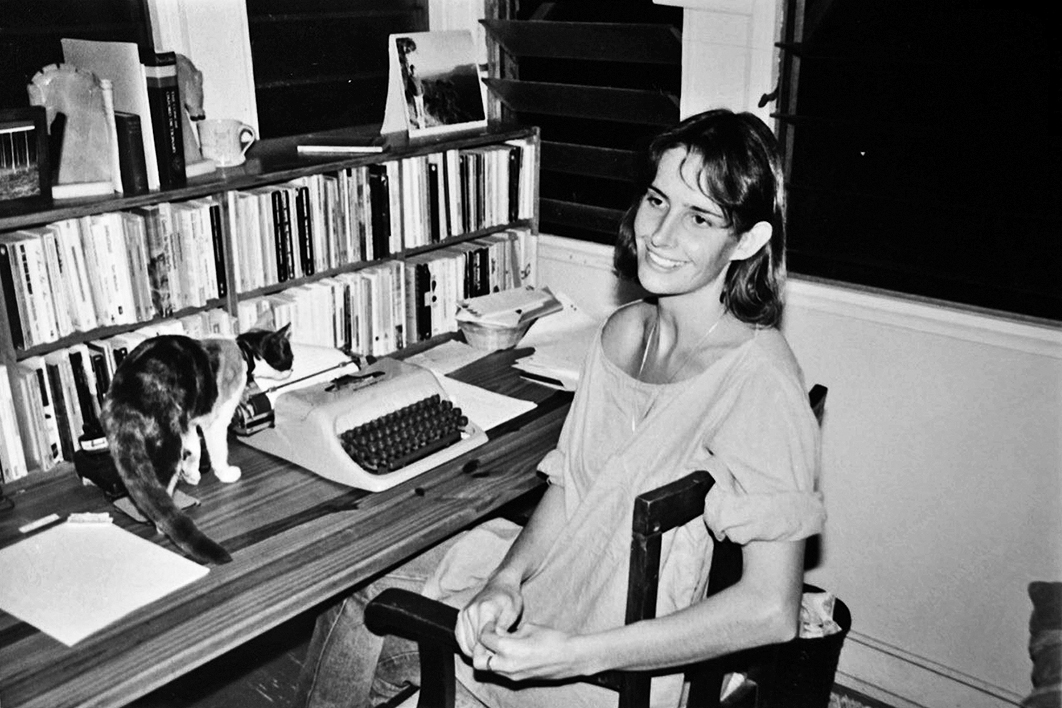

And there she is on the cover of Brennan’s excellent new biography, Leaping into Waterfalls: The Enigmatic Gillian Mears. That wide smile that drew so many people to her, the open face, the loose hair, the eyes partly closed against the light.

The metaphor of the title’s waterfall comes from Gillian Mears, of course. She loved the rush of water, the temptation to leap, and it was a terrible day when the MS made even a dip impossible. When she dreamed of waterfalls, the allure of the water, she’d be woken by the terror of going over into the “maelstrom of change,” knowing that the longing to leap, leaving “the safety of the little upper river shallows” could ultimately mean “courting death.”

I first encountered Gillian Mears when she arrived as a student at the University of Technology Sydney in 1983. I was on the creative writing staff, and that year saw a remarkable intake of talent that none of us will easily forget. (Nor will we forget the sense of alarm as we tried to figure out how to engage them and keep their interest, how to stretch ourselves to keep abreast, and possibly also teach them something.)

Even among that talent, she stood out. She rarely spoke in class, and yet hers was a dominant presence. How many nineteen-year-olds (when pressed) tell you the writers they intend to equal are Randolph Stow and Carson McCullers? And afterwards, after she had graduated and I had left, I worked as an editor on her novel The Grass Sister; we became friends and would spend time together when in the same city. I was in Paris briefly when she was at the Australia Council’s Keesing Studio, and according to Brennan’s biography, she remembered me showing her “how to see Cézanne.” My memory is of seeing some early Kandinsky semi-abstract Impressions with her, those blue leaping horses, and understanding (at last) the exhilaration of the rider as a metaphor for the artist: that surge of energy, its rhythm and its timing.

All this by way of declaring an interest. I get a few mentions in the book, which might have eliminated me from writing this essay, but I am glad it did not. If anything, it has made the task harder. I thought I knew Gillian Mears well, if intermittently, but reading Leaping into Waterfalls I realise how little I really knew. How little she let herself be known. Enigmatic, yes, and also shapeshifting. She was selective in the selves she allowed to be known, and she was convincing in their fullness. I knew one or two of those selves, or maybe three or four, and such was her power that I took them to be more. The little I knew her, and all that I did not know — or knew only in a tidied-up version (that wasn’t that tidy) — has made me all the more aware of the challenge Bernadette Brennan faced — and her achievement.

Leaping into Waterfalls is Brennan’s second biography of a writer. A Writing Life: Helen Garner and Her Work was published in 2017. While Garner, like Mears, is a writer whose personal and fictional worlds meld, Brennan’s book about her — as is clear from the title — stays largely within the bounds of “literary biography,” with the emphasis on a critical reading of the work. It was deservedly well received. While her “primary intention” with this next biography is to celebrate Mears’s work, and her critical eye is beautifully evident, Leaping into Waterfalls is a leap into the rocky waters of biography — into the life narrative of a brilliant, complicated writer within, through and beyond the work.

Gillian Mears left a large archive of diaries and letters, which went in batches to the State Library of New South Wales when she needed money (which was often). After the diagnosis of MS, she annotated the archive — a “careful archaeology” — with notes addressed to her biographer. She didn’t know who it would be — she only met Bernadette Brennan once — but she knew there’d be one. She put a lot of effort, Brennan writes, into “steering curious eyes, emphasising some pathways, and obscuring others.” Pages have been removed from the diaries that had accompanied her since the death of her friend Sandra Watkins. Her “need to understand herself was one of the central forces of her imaginative life,” Brennan writes, and she knew her diaries would be a prime source. Could the diaries be trusted, she asks rhetorically. Yes, she writes, as diaries. As one lens among many through which to view the enigmatic Gillian Mears.

Mears was also a prodigious letter writer; “a form of flirtation” she called it. Very few could resist her, and it was a joy to see her handwriting on an envelope in the mailbox back in the days when such pleasures existed. (She took to email, of course, but it was never the same, and she kept up the letters until very near the end.) She initiated many of these correspondences with “paper friends” who came to include Gerald Murnane, Helen Garner, Kate Grenville and David Malouf, as well as Bruce Pascoe (who published her first short stories) and Ivor Indyk (who published her brilliant late essay-story, “Alive in Ant and Bee”). Elizabeth Jolley was one of the few established writers who resisted her overtures, but even she eventually succumbed. We were, I think, a small corner of those upper river shallows where she could go for safety (or at least endorsement as a writer).

And then there were the letters, so many of them, that she wrote to her lovers, her family and the friends of her generation. Letters of love, letters of jealousy, letters written in conflict and crisis when a sister or friend felt betrayed by something in her fiction, or as a love affair crashed into the water. After the short-lived marriage to her English teacher, Gillian’s passions became as wild and wayward as the rest of her life. Her “sensuality and sexuality,” Brennan writes, “were at the core of her identity and her exploration of each informs all her writing. She could strip herself bare, both metaphorically and in a later essay accompanied by a Vincent Long photo, literally.” (The photo of her painfully thin, lying naked with her walking stick, is among the many included in the book.)

Writing was, for Gillian, an arena of both risk and sanctuary. It was a reckoning, a necessary process of understanding — and transformation. But in stripping herself, she could also strip others, and when she did, to those who knew, she could appear — and be — indifferent, harsh, even cruel.

Pity the lovers and siblings of writers. Nabokov’s “great deceivers,” Janet Malcolm’s “burglars,” writers are by nature, Gillian would say, spies and eavesdroppers. Those who knew and loved her, or had loved her, had reason to feel the sting of exposure. And from their perspective it didn’t help that she spoke of her fiction as her own “peculiar” form of autobiography. Brennan amends this to “heavily autobiographical while simultaneously standing apart from her life story.” It was the standing apart, that mysterious process of fictional transformation, that made Mears the writer she was. The challenge for her biographer — as with the biographers of all (or most) writers — is how to weave a narrative through those complex entanglements to comprehend the life in all its messy contingencies — and its transformation in that “apartness” of the fiction.

It was a task made harder because, while Gillian died in 2016 at the age of fifty-one, most of those whose stories intersect with hers are well alive. When Bernadette Brennan approached her once-lovers, there’d be admissions of “heightened anxiety, even sleeplessness,” before meeting her. More stories, more versions, more justifications, more obfuscations. She takes her task as biographer to be one of listening; not judging or pleading but understanding the case of Gillian Mears.

And as biographer, Brennan makes few, if any, overt comments — even about some of the most dreadful moments. When the MS has Gillian (often literally) on her knees, she falls in with an ex-junkie, macrobiotic “healer” — a lover who is certain the “malady” is one of unresolved spiritual conflict. At his isolated farm, she deteriorates, dragging herself across the floor and through the mud, and still the healer-lover misses the heart inflammation that would have killed her if he hadn’t got her to hospital literally at the last moment. She was flown to Sydney, and I was one of those who visited her in the Prince of Wales hospital after the open-heart surgery.

It wasn’t the only degradation Gillian put herself through rather than succumb to the diagnosis and treatments offered by medical orthodoxy. Another “miracle cure” was conducted at the top of a mountain (in Venezuela) that she had to crawl up. And still Brennan resists interjecting, letting the narrative do its work, gathering rhythm and pace, holding steady the varied lenses, to bring us to a place of powerful (and sometimes painful) understanding.

In a deft move, Leaping into Waterfalls repositions Gillian Mears’s distrust of medical authority as part of the radical uncertainties she gave voice to in her fiction — as a migrant, a bisexual, an erotic adventurer and — in yet another paradox — a cosmopolitan who preferred to dwell close to the soil. Tents, caravans and huts from which she could see the sun rise meant more to her than even a Paris studio. And as with so much else in her life, her hope, her belief in other ways of being, linked her own bodily ailment to the psychic and spiritual disorder of the society, the culture, the polity in which she lived.

When she finally accepted the “fate,” the reality of MS, she turned to herself, to the repository of courage that had always been there, and to solitude as another form of sanctuary. While it was still, just, possible, she took off alone in an old, converted ambulance — Ant and Bee — set up so that she could live out in the bush for two weeks at a time, writing, feeling the earth beneath her feet, letting herself down into that realm of imagination that could “thrash around in the mud” (as she put it) and remake itself in fiction. Life in Ant and Bee was a last adventure into the (semi) wild before she would be confined to a wheelchair and bed. The waterfall exchanged, in Brennan’s luminous telling, for “the River god of imagination,” the horse for the pen.

Gillian Mears took her last step during the editing of Foal’s Bread (2011), in which she tells the story of a horseracing family whose daughter “leaps into history” when she wins a major jumping competition, only to realise she has alienated her jealous and disappointed mother, unleashing sorrows she was born from. Set before Mears was born, and paying homage to a “now-fading Australian vernacular,” it might seem her least autobiographical novel. And yet, Brennan writes, “the narrative gathers together many of her most precious and abiding concerns” — of a family both riven and bound together, the repetitions of histories, small and large, that can cut across the boldest of individual choices. It is a novel, written long after Gillian had last been helped onto the back of a (pliant and retired) horse, about the power of riding, that connection to the horse and to “something bigger” at that moment when the horse makes the leap, “climbing up and up,” a jump unlike any other.

Writing of this last novel in words that match Mears’s own, Bernadette Brennan draws together the paradoxical threads of Mears’s power as a writer, and the brutal loss of bodily capacity. The metaphor of the rider as the artist, that Kandinsky-like surge of energy, is rendered most powerful at a time when that dramatic moment of leap can no longer be lived.

Foal’s Bread won the 2012 Prime Minister’s Literary Award, and among the photos included in the biography is a gorgeous one of Gillian in her wheelchair receiving the award from Julia Gillard. There’s also one of her at the age of thirteen, leaning forward as her horse leaps over a fence of old tyres.

The harsh reality of MS meant that “Mears’s long obsession with death was coupled with her consciousness of what her life might mean,” Brennan writes. Not for her the denial that allows most of us to live as if the inevitable can be endlessly postponed. Death came to Mears step by relentless step as the paralysis that first took her legs continued its march through her body. By 2016 she could barely hold a pen, or swallow. She was facing the full paralysis of quadriplegia with all its tubes and catheters. As an advocate for voluntary euthanasia, and in possession of a vial of Nembutal, she had long decided to take control of her dying. Yet it’s one thing to have the vial, another to find the courage to drink it.

In those last years in her wheelchair, while the top half of her body was still mobile, she learned to dance, most beautifully, as she did at her fiftieth birthday in 2014, a large gathering at Grafton’s Barn, with everyone dancing in celebration of her life. “I want to touch life like the green twig touches the river,” she wrote near the end. While she had “given up on the idea of miracles,” Brennan writes, “she was not quite finished with blessings.”

It wasn’t, of course, quite that easy. But it’s not untrue to say that she did go dancing into that dark night “surrounded by love,” and at a time of her own choosing. In the early hours of the morning of 16 May 2016, she wrote her final goodbyes and then drank the Nembutal, mixed with Bailey’s Irish Cream to temper its ugly taste.

In a final project Gillian asked friends and family and fellow writers to send her fabrics that had meaning, or to sew panels of embroidery, which she made into a quilt that was there on the wall of the Barn at her fiftieth birthday. Her last metaphor, maybe, for the life she’d lived and danced and written. Quilts, waterfalls and safe shallows, horses and their riders. Bernadette Brennan’s gift to Gillian Mears — and to us her readers — is to bring us to that last, inevitable act in life, her death, with luminous clarity. And through it all, the revealed and the concealed, the courage and the abjection, the joyous and the appalling, we end up, with Brennan, liking and respecting — as well as understanding — the enigmatic Gillian Mears.

With Leaping into Waterfalls, Bernadette Brennan is confirmed as one of our finest biographers, to be celebrated not only for this vivid portrayal of a writing life, but for her facility with the art of biography in this complex, contemporary present. •

The publication of this article was supported by a grant from the Judith Neilson Institute for Journalism and Ideas.