How many Australians have already returned their same-sex marriage survey to the Australian Bureau of Statistics? Might it be about 2.4 million? Or more than double that, 5.8 million? Or could it be as high as 10.4 million?

The people at Newspoll, whose results are published in the Australian, estimate the first figure. They posed the question in their fortnightly voting-intentions survey between last Thursday and Sunday and found that only 15 per cent had already “voted.” The electoral roll contains a touch over sixteen million people, and 15 per cent of that is 2.4 million.

Essential Vision’s latest survey, conducted from Friday to Monday and published in the Guardian, found 36 per cent. And “leaked” internal polling from Yes campaign headquarters (online panel, 1000 respondents, Thursday lunchtime to Friday lunchtime) throws up some startling numbers: 90 per cent have received their forms, 88 per cent of those have filled them in, and 73 per cent of the 90 per cent have already posted them back.

Now, leaked internal polling should always be handled with kid gloves. It is placed in the public arena for a reason. And this finding would mean that 65 per cent of voters have already returned their forms, which is flabbergasting.

But what could account for the difference between Newspoll and Essential? Newspoll had an introductory question, “Are you in favour or opposed to the postal plebiscite?” (Presumably this was preceded by something like, “You may have heard about the postal plebiscite run by the ABS to change the law to…”) Then they asked how the respondent voted or will vote, how likely they are to vote, or if they indeed already had.

Essential skipped the first question. Could that account for the difference? Newspoll’s question includes the words, “voting in the plebiscite is not compulsory.” That might explain the divergence, although both get about the same percentage of respondents saying they won’t vote. In six weeks’ time, when the results are in, we’ll know much more about this question.

Leaving that aside, what do these surveys tell us about what the Yes and No votes are likely to be?

Here, the two pollsters sing from the same sheet: 58 per cent Yes to 33 per cent No for Essential, and 57–34 for Newspoll. Assuming the undecideds don’t vote, that comes to about 63 or 64 per cent Yes. Assuming they do vote, and split 50–50 between Yes and No, those Yes numbers fall by only a little over a percentage point.

The two pollsters’ Yes or No questions are different, with Newspoll asking how people will respond to the survey and Essential replicating the ABS’s question, “Do you support changing the law to allow same-sex couples to marry?” This is a potentially important distinction because the No case is attempting, in a reprise of the 1999 republic referendum, to convince marriage-equality supporters to vote No because we haven’t seen the legislation and it’s better to be safe than sorry. Ideally, it would love to turn the survey into a vote against “cosmopolitan elites” and “bullies” — 1999 again.

I much prefer the Newspoll question, but it’s good to have both because we can watch for divergence between the two. Unless that “leaked” internal polling is right, of course, in which case it’s pretty much all over.

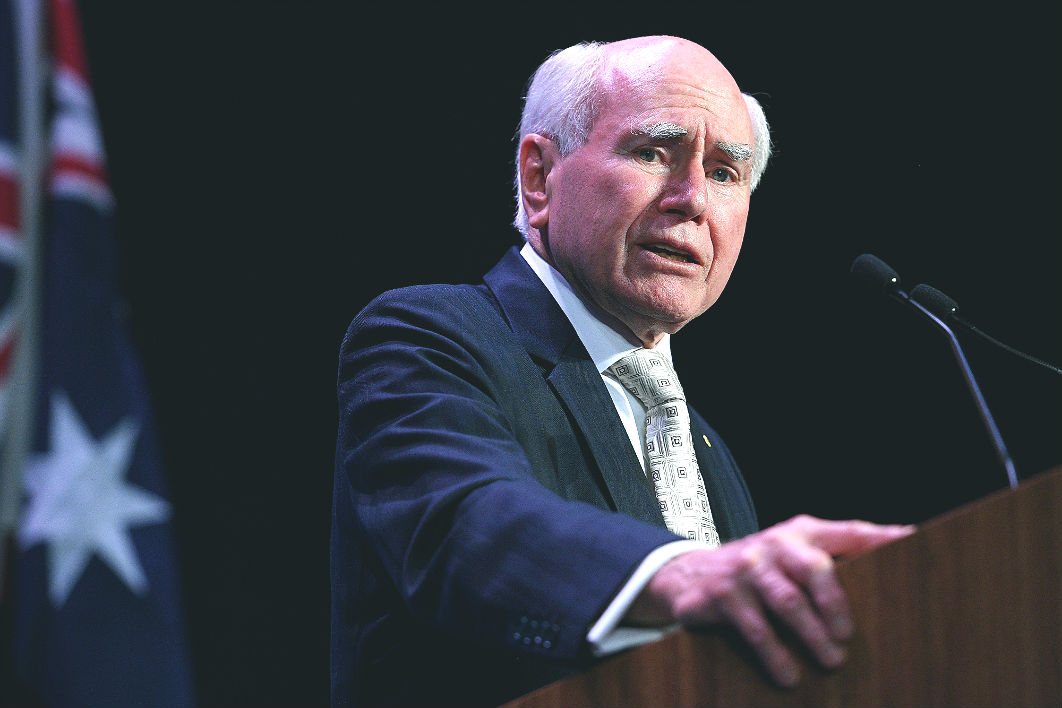

This campaign has also seen the reappearance of that old stager, John Howard, proselytising for the No side. Commentators have been cooing, equality supporters trembling, for the Master — he who held the electorate in the palm of his hand for over a decade — is back, weaving his magic.

Now, it’s true that most Australians retain positive feelings towards Howard and his government, representing as they do life before the bottom fell out of the economy. Wallets were open, spending was in fashion, government coffers overflowed, and it seemed the good times would last forever. Talk about stability: one prime minister for almost twelve years. Most believe Howard ran a good government and ran a good economy. He routinely tops the poll figures for “best” recent prime minister.

But that doesn’t make him a persuasive figure on social issues like this. Apart from anything else, Australians also believe he was a very clever politician, which is another way of saying he stretched the truth from time to time. This was, after all, the prime minister who in 2004 felt the need to reclaim the word “trust,” as in: forget about who you trust to tell the truth, who do you trust to run the country?

Politicians are never as wonderful or as terrible practitioners of the art as history depicts. They make their own luck, to a point, but are also hostage to timing and good fortune, and most importantly to economic and electoral cycles.

Some Yes supporters, in their panic, are recalling how eighteen years ago the evil genius manipulated the republic referendum to make it a vote on a particular model, rather than a Yes or a No. Oh no, he’s going to do it again!

But that 1999 hurdle was a constitutional reality. Any move to a republic will require majority support for a specific change (and a majority in four states), whether or not an “indicative plebiscite” is held first. That wasn’t John Howard’s doing.

So, yes, he’s been up to his old tricks, campaigning against change, which is what all politicians are most comfortable doing. But his rhetorical skills are not all they’re cracked up to be. And his special topic, religious freedom, is a niche issue.

Anyway, we haven’t heard much from that quarter over the past week. Maybe he’s been shown some internal polling. ●