Ranged along Australia’s eastern shores is an archipelago of sites associated with the four-month visit of Captain James Cook and the Endeavour in 1770. Cook first fell in with the coast on 19 April after his second-in-command, Zachary Hicks, sighted the lands of the Krauatungalang people of the Gunai nation. After staying on Dharawal and Guugu Yimithirr lands, he ended his Australian visit on 22 August with a ceremony of possession on an island inhabited by the Kaurareg, Gudang Yadhaykenu, Ankamuthi and others.

We remember these sites not only because they’ve been recounted and chronicled in books. Each is also an active site of memorialisation, studded with monuments and enlivened across the years by performances and other memory acts. Cook’s declaration in August 1770 was only an indeterminate moment of possession, as Bain Attwood has recently reminded us. It was the settlers and colonisers who came after who enacted that claim, and went on to cement themselves in this stolen land by building monuments to Cook throughout the country and purchasing his relics to fill their public libraries and archives.

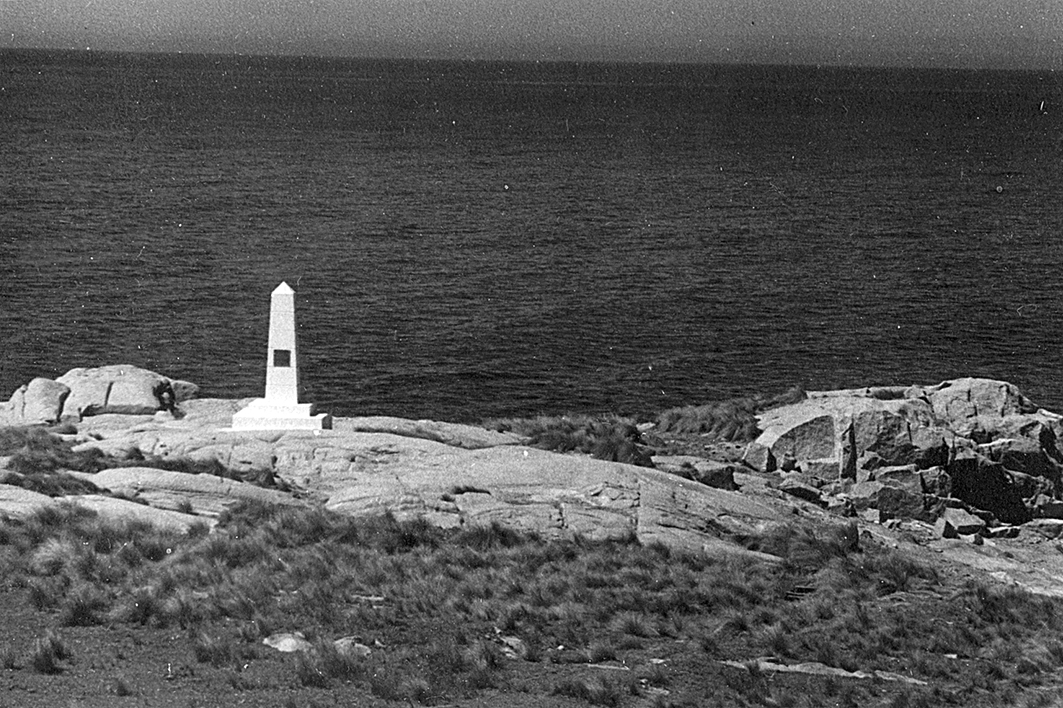

One of those monuments is an obelisk erected at Point Hicks on the southeast coast of Victoria in 1925. When we look at this small, rocky cape we see a landscape of Cook memorialisation, part of a global chain of monuments dotting Australia’s and other nation’s coasts. About one hundred metres due south of the lighthouse built at Point Hicks in 1890 (when it was still known as Cape Everard), the obelisk asserts that this land was the first seen by Cook in Australia. With its classical form, it seems so intentional. Yet a churn of bureaucratic correspondence, indecision and delegation — partly reflecting the focus on Possession Island in the north — lies behind the monument as it stands today.

The story of the obelisk, and of a copy made and sent to Britain in 1934, highlights the ambiguities, evasions and ambivalences that have been part of Australia’s long remembering and venerating of Captain Cook. The obelisk and the rocky land at Point Hicks testify to the great lengths to which white settler Australians have gone, including moving the very earth, in justifying their presence on stolen land.

The early decades of the twentieth century were a rich time of memory work in Australia. Historical societies formed in many of the states, and civic-minded people banded together in their communities to erect memorials and monuments that spoke of the growing maturity of their nation. It was in this context that the council of the Sydney-based Royal Australian Historical Society called on the prime minister in May 1923 “to ensure the reservation for all time of Possession Island (near Cape York) where Captain James Cook performed the ceremony of taking possession of the eastern portion of New Holland” and “cause measures to be taken to erect a memorial to Captain Cook upon that Island commemorating that fact.”

Two men pushed this proposal. The first was the president of the society, noted NSW agricultural administrator W.S. Campbell, retired from bureaucratic toil and enjoying life as an amateur historian and Cook buff. The other was the society’s honorary secretary, Karl Cramp, an “exacting” schools inspector, “feared by teachers,” whose “textbooks indoctrinated generations of schoolchildren in hero-worship, the Whig interpretation of English history and a jingoistic view of Australia bonded to Britain.”

Public memorialisation of Cook in Australia only began in earnest in the late nineteenth century. His first public statue was erected in the Sydney suburb of Randwick in 1874, and the statue that still dominates Sydney’s Hyde Park, with its proclamation that Cook “discovered this territory,” was unveiled before a crowd of 60,000 in February 1879.

With “explorers” a favoured subject of public memorialisation in the colonies, and later in the newly federated states, cairns and other blocky and rocky monuments came to stud the landscape. In 1911, for example, the Victorian education department, urged on by the Australian Natives’ Association, declared that 19 April each year would be Discovery Day, when students would think about the explorers. In the following decade, Victoria was even home to an explicit “memorial movement” dedicated to encouraging the building of structures that might cause locals to reflect on history and nation. This memorialisation came at the same time as a consequential and pervasive forgetting. The colonists and citizens of the new nation were noting the demise of the Aboriginal people but burying the truth of their violent dispossession.

The Royal Australian Historical Society’s hope that Cook would be memorialised at Possession Island was part of this larger cultural push. Yet, when it did ask the prime minister for funds to support its proposal, the bureaucracy of the young Commonwealth — still based in Melbourne — was not entirely enthusiastic. An officer of the home and territories department thought the prime minister had no power over what was plainly a Queensland government concern. Perhaps fearing a great outlay of money, the department was inclined to rebuff the proposal.

With gentle mockery, the Sydney Sun depicted a scene of bureaucratic confusion:

There were searchings of heart and of maps lately in the Department of Home and Territories, Melbourne. A letter drifted into the department from the Royal Australian Historical Society of New South Wales, suggesting that a monument of some kind should be placed on Possession Island. The question was where and what was Possession Island? There seemed to be no official record of such a place.

The playful report said that “an outside expert was consulted, and he pointed out that it was the little island just off Cape York… The department breathed again.”

That outside expert was Kenneth Binns, senior librarian for Australian collections in the Parliamentary Library, the precursor of the current National Library. With the library about to receive Cook’s Endeavour log, for which the Commonwealth government had recently paid £5000 at a Sotheby’s auction in London, Binns was in a thoroughly Cook mood.

By early July, he had marshalled his thoughts and prepared a memorandum on Possession Island. He reminded the department’s secretary that the Commonwealth had only recently purchased Cook’s journal. And he conveyed information from Captain John King Davis, famed Antarctic navigator and the Commonwealth’s director of navigation, that Possession Island “is now uninhabited, and very seldom visited.” Binns also argued that it was worthwhile to commemorate not just the last place Cook visited in Australia, but also the first place sighted: what Cook had named Point Hicks but was officially known as Cape Everard. “Speaking personally,” he went on, “I may say I am thoroughly in sympathy with the suggestions of the Historical Society; but would like to see coupled with them a similar suggestion for the commemoration of Point Hicks.”

Sensing that the Commonwealth government would not entertain a grand gesture given the large financial outlay already made for Cook’s journal, Binns thought “a simple brass-plate” would suffice to commemorate “the Historic occasion.” Given that the sites were “seldom visited, a brass-plate suitably inscribed and affixed to a suitably situated rock, would meet all requirements.” He thought that a committee of the University of Sydney’s G.A. Wood, the University of Melbourne’s Ernest Scott and Cramp could easily compose the inscriptions.

Federal cabinet approved this modest suggestion at the end of August 1923. But what followed was almost a year and a half of slowly paced developments relying on a glacial exchange of correspondence across the country. Despite being one of the forces behind the idea, Cramp, along with Wood and Scott, only finally agreed to the inscriptions in May 1924.

There was also the nagging question of whether Cook had actually seen Point Hicks on that April dawn in 1770. In 1907, Melbourne land surveyor Thomas Fowler had argued forcefully to the Geographical Society that the voyage records and charts could not substantiate the claim. Unfortunately, Fowler was up against the prominent historian Ernest Scott, who vigorously defended Cook’s navigational competence. Kenneth Binns was conscious of these disagreements and thought the plaque should be “couched in fairly general terms, lest some hyper-critic should arise and question its correctness.”

In November 1924, eighteen months after the proposal was agreed on, the memorial plate was finally complete. But where exactly on Point Hicks should it be mounted?

Binns had asserted a year earlier that the plaque could simply be given to the navigation department and they could affix it in some suitable way. Now, for the first time, an obelisk was proposed, probably by the director of lighthouses, and duly commissioned. It was constructed of concrete in a Melbourne dockyard in early 1925 and sent by the Lady Loch to Cape Everard in May. (That it was made of concrete rather than a more noble material made it a structural sibling to the lighthouse itself, which had been the first constructed of concrete in Victoria when bluestone and locally sourced granite proved too expensive.)

More correspondence ensued. “In what Direction is the Brass plate to be?” the lightkeeper asked in June 1925. “Facing the sea or facing towards the station?” Towards the station, came the answer, with the additional injunction that “the greatest care should be taken to set the shaft true; the slightest deviation from the perpendicular will spoil the whole effect.”

By the end of August the lightkeeper reported that the obelisk had been “completed to the best of my ability, your instructions having been strictly carried out.” The instruction to paint it “mill white” was sent in late October and the lick of paint applied in early December. It was a well-meaning if slightly disorganised affair all round. Two and a half years had passed between the proposal and the finished product.

But who would even see this obelisk? Was there a vain hope that passing vessels would see the white pillar? One government engineer thought that the obelisk might be seen from a ship up to a mile away. In his recent book Seashaken Houses, author and building conservationist Tom Nancollas reminds us that lighthouses are “designed expressly to repel, to emphatically not be seen at close quarters.” What then of the obelisk that might stand proudly though diminutively beneath that repellent building? Cape Everard was not the accessible and well-tramped site in a national park that it is today.

The concrete obelisk joined with the concrete lighthouse to demarcate the nation’s edge, to attest to the division between land and ocean, to be a sentinel of history. Its erection also meant that three signal sites of Cook’s Australian encounter — Point Hicks, Botany Bay and Possession Island — were graced by this classical form.

And so the mill-white concrete obelisk stood there, little thought of, until another stone monument was made to move across the globe. In 1933, in the Yorkshire town of Great Ayton, a stone cottage was put up for sale. It had been owned by James Cook’s father, and local lore had it that young James had grown up there. The auctioneer was only too happy to play up that legend.

News of the sale reached Victoria, where the state centenary was due in 1934. The government had gathered a committee of local worthies to plan for the occasion, among them Russell Grimwade, steward of a pharmaceutical fortune, pillar of Melbourne society, philanthropist and dedicated Australian antiquarian. Having learned of the sale and proposed purchase of the cottage to the Victorian premier, Grimwade had the Victorian agent-general in London inspect the building and ask whether the family would sell to a buyer who wanted to uproot the building and send it to one of the dominions. Grimwade’s offer of £800 for the cottage easily outbid the highest local offer of £300, and he stumped up a total of £2000 for its purchase, dismantling, transport and re-erection in Melbourne.

Russell Grimwade in his Flinders Lane office, Melbourne, in 1931. University of Melbourne Archives, 2002.0003.00503

Not all were happy with this philanthropic gesture. Apart from some public friction in Melbourne about where exactly the cottage would be put, the good burghers of Great Ayton were none too pleased that a local landmark would be shipped away. How to placate them? The Victorian premier suggested a plaque: a trifle to forge and despatch to Yorkshire. Grimwade agreed, adding only that “the record we send should take the form of a stone [or] boulder from that part of the coast of Victoria which was first sighted by Cook.” Clearly aware of the disagreements surrounding the location of Point Hicks, he also told the premier that he was “having it confirmed at the moment by a competent authority as to which point this was and will advise you later, and I am preparing suggested working for engraving on the stone.”

Once again John King Davis, the gangly and storied Commonwealth director of navigation, played a vital part. Like Cook, Davis was a ship’s captain who had ascended to higher latitudes, passing the Antarctic circle and meeting with the ice. Davis and Grimwade — both members of the Melbourne Club — were friends, and Davis, as a fine mariner and navigator himself, was the “competent authority” Grimwade had mentioned to the premier.

Davis wrote to Kenneth Binns, by then the national librarian, to ask “what evidence was before the Government when it was decided to place the obelisk at Cape Everard as being the first land sighted from the ‘Endeavour’?” Davis had done only a little research on the matter, and what he read didn’t stack up. “From a perusal of Cook’s own Log,” he wrote, “it appears the first land sighted from the ‘Endeavour’ was not on the seaboard at all and if you have any papers which will assist in clearing up this point I should be very grateful for the opportunity of seeing them.”

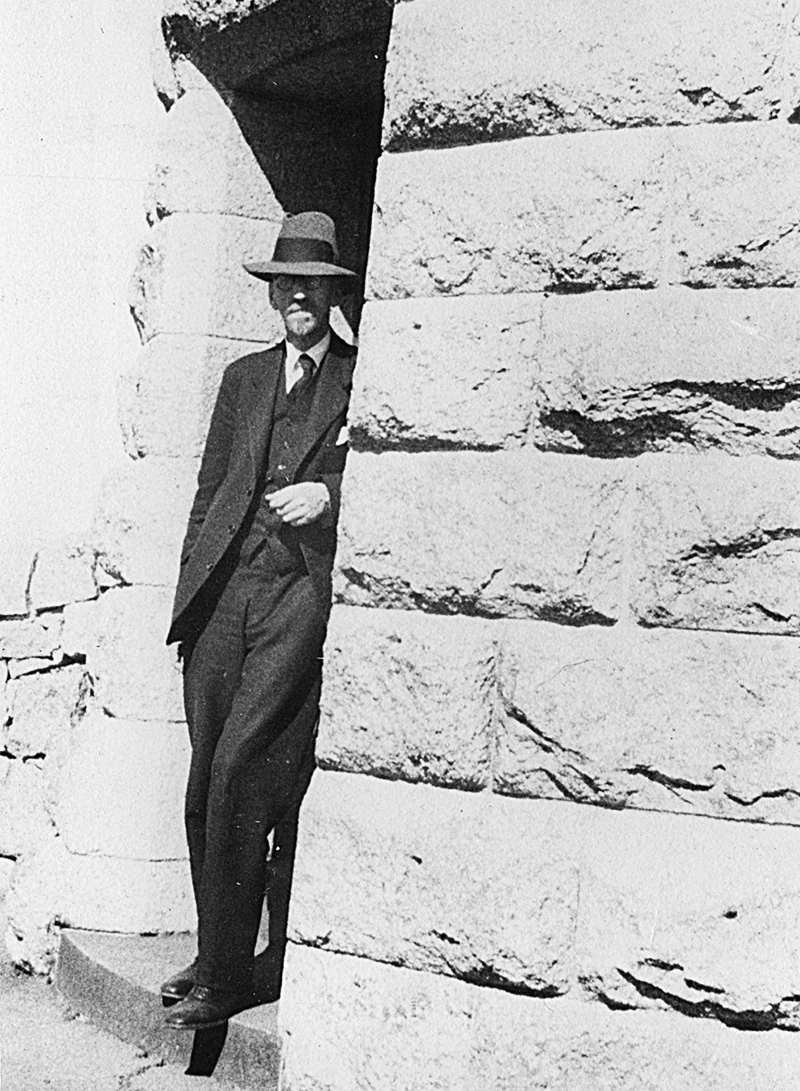

J.K. Davis at Cliffy Island, 1933, photographed by Russell Grimwade. University of Melbourne Archives, 2002.0003.00057

Had Davis forgotten the events of 1923 and 1924, when he had played a minor role in the erection of the obelisk? Perhaps he was too efficient an administrator, and had redirected Binns’s request to the director of lighthouses, his subordinate, without a second’s thought. Binns was clearly sympathetic to the claim that Point Hicks was, in fact, the land seen by Hicks and Cook.

In late 1933, in pursuit of navigational exactitude and not entirely believing earlier investigations, Davis had one of his officers “transfer Cook’s original chart which is reproduced in the Historical Records of New South Wales to the modern Admiralty Chart.” This Davis sent to Binns for the National Library.

A year later, still not satisfied, Davis appealed to that greatest of maritime authorities, the hydrographer of the Royal Navy, for “an examination of the original records.” But those simply confirmed the problem: that Cook and Hicks, with some eighty fathoms of water beneath the Endeavour, probably did not see land at 6am that morning.

The validity of Point Hicks wasn’t the only matter in question. Grimwade’s attempt at civic munificence was undermined when many queried whether Cook had anything to do with the cottage. Had the future seafarer grown up in it? No, was the short answer. Had he ever visited his parents there? Yes, but only once… probably.

Grimwade battled doubters from the date of the purchase up to the inauguration of the cottage in the Fitzroy Gardens on 15 October 1934. His definitive and emphatic statement was that “it has been proved beyond all doubt and has become a recognised historical fact that he lived in the cottage for three weeks after he returned to England following his discovery of Australia.” He was also sure, though without evidence, that Cook “lived there for a good deal longer than that.”

Grimwade’s was not simply an antiquarian urge. In valorising Cook and appropriating him for the task of sanctifying the state of Victoria, he was celebrating a specific form of the Australian nation — a nation of white Britons who had made purportedly useless land into a productive home. Given his devotion to the explorers who had “opened up” the continent, his erasure of Aboriginal people from Australia’s past and future was near complete.

Grimwade made some of his sentiments explicit in a Sunday evening radio broadcast in September 1933. “Providence,” he began, “has granted to the people of Victoria one hundred years of peace in our land in which to transform it from uncultivated bush to a settled productive area of happy homes and bountiful harvests.” The Indigenous owners of this land, he opined, “had not reached that stage of development that had taught them to cultivate a tree bearing food nor an annual crop.”

He went on to utter the national lie of a settler colony founded on death and dispossession: “The timid and ineffective Aboriginal has been quietly dispossessed with the minimum of effort and inhumanity… Australia is the only important area of the Empire in which the blood of battle has not been spilt.” How was “the poor primitive blackfellow” to face the nation that had sailed the “uncharted seas” and “provided ample proof of their fitness to survive”?

The granite of Point Hicks, photographed by Russell Grimwade in 1933. University of Melbourne Archives, 2002.0003.00480

Grimwade wasn’t much impressed by the Gippsland coastal landscape either. For him, Cape Everard was “a lonely spot,” an inaccessible landscape of “sand, wind and tea-tree.” This sandy, scrubby land defied not only the individual wanting to pass through it but the entire imperial project of cultivation and improvement. It “offers no reward for tilling and no hope for harvest. It is entirely uninhabited save for the population of native animals it bore in Cook’s day — reduced in numbers of larger marsupials, but still prolific of wallabies, lizards and many snakes.” The rhetorical ease with which Grimwade ignored the dispossession of the original owners and minimised the ecological ravages of colonisation is stark. This is what the obelisk was for.

Grimwade also painted himself as a dynamic and public-minded businessman. Despite the fact that he would have clubbed and dined with such people in town, and despite his reliance on Davis and a whole cast of public servants to convey him and the stonemasons he employed to Cape Everard, he proclaimed that it was “easy for a patriotic Administrator in the comfort of a Melbourne office to say it shall be done, but mark what follows this simple order.”

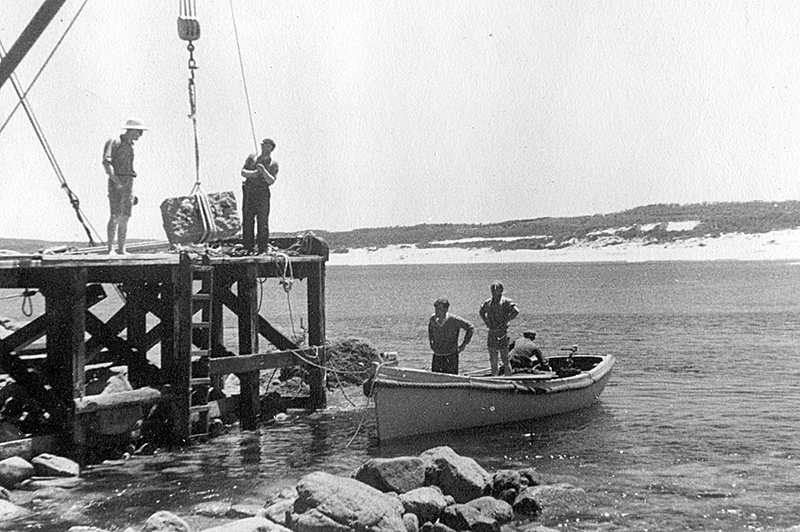

Grimwade didn’t simply order that some stone from Cape Everard should be sent to Yorkshire as a modest token of thanks. He went to the small headland himself to inspect the site and meet the stonemasons sent to quarry the granite. He joined the Commonwealth lighthouse ship Cape York at Williamstown on 30 October 1933 for one of its quarterly resupply visits to Victoria’s eastern lighthouses. They stopped at Wilsons Promontory and Cliffy Island before reaching Cape Everard, and would visit Gabo Island on the return journey to Melbourne.

The Melbourne Age reports on the expedition on 26 October 1933. Trove

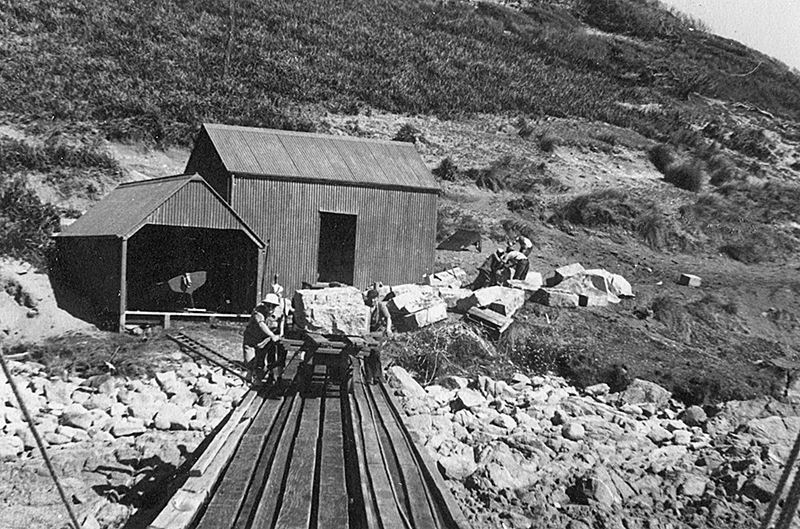

A keen amateur photographer, Grimwade travelled with camera in hand to document the journey. On 1 November, he tramped around Cape Everard, taking in its many views, while the stonemasons (who had travelled over the difficult country with their tools) loaded up the ship with the granite. In a short newspaper travelogue, Grimwade reported that the masons “chose a spot less than 40 feet from the obelisk” from which to extract the rock.

Moving the granite blocks at Point Hicks, photographed by Russell Grimwade. University of Melbourne Archives, 2002.0003.00066

The town clerk of Middlesbrough — the borough in which Great Ayton sits — had expressed gratitude for the offer of the obelisk to replace the cottage, but wondered if the new memorial did, in fact, have to be an obelisk. Unfortunately, he informed the Victorian agent-general, the cottage was already in sight of the Cook monument on Easby Moor, which was itself an obelisk. Even the agent-general was unsure: were the memorial stones at Cape Everard in the form of a cairn or an obelisk?

Grousing at the style, cost and nature of memorialisation was part of the process. Kenneth Binns, reminiscing about his own part in the memorialisation of Cook, wrote to Grimwade to recollect that the Queensland Geographical Society had itself complained in 1924 that the obelisk erected on Possession Island was at the landing place rather than at the top of the island. Binns thought that the extra cost of having it up high wasn’t warranted, given so few people would actually visit.

Loading the granite blocks, photographed by Russell Grimwade. University of Melbourne Archives, 2002.0003.00396

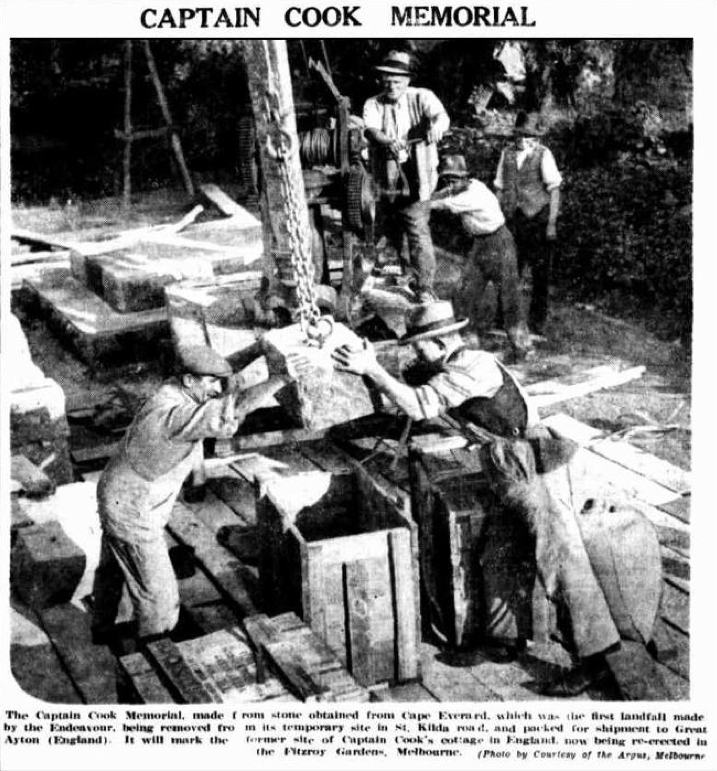

The stones disembarked with Grimwade and Davis at Williamstown, there to be prepared for shipping and construction. In late June 1934, to whet Melburnians’ appetite for the cottage slowly being reassembled in the Fitzroy Gardens, the new obelisk was temporarily erected on St Kilda Road, just near the Princes Bridge. So out of reach at Cape Everard, the obelisk was now accessible in ersatz form — or, rather, in a finer granitic form than its original concrete body — close to the city. The City of Melbourne even saw fit to have it floodlit in the evenings. Then, in early July, it was again on the move, bound for Yorkshire aboard the steamer Hobson’s Bay.

The Hurstbridge Advertiser reports progress on 6 July 1934. Trove

On 15 October 1934, having made it to Yorkshire safely, the granite monument was unveiled in Great Ayton on the same day that Cook’s cottage was inaugurated in the Fitzroy Gardens. The exchange of geology and memory was marked, naturally, with speeches. At the unveiling of the obelisk, the Victorian agent-general declared that “posterity will judge the nations by the heroes they crown… Cook’s character made the British Empire as we know it today.”

In his 1968 Boyer Lectures, After the Dreaming, the anthropologist W.E.H. Stanner observed that 1934 might be seen by some as a turning point in Australian Aboriginal history, that people were realising something had to change between White and Black Australia. For him, though, it seemed “to have been just another year on the old plateau of complacence.” Russell Grimwade’s words and his physical interventions into that “lonely spot” on the Gippsland coast testify to this. Stanner also referred to “lonely places” in the second of his lectures, “The Great Australian Silence.” For Stanner, however, the term reflected the increasing realisation among Australians that “intolerable things were happening in the lonely places.”

We can counteract the glib and unstoried obelisks that venerate Cook by remembering the words and efforts of those who put them there in the first place. When we do uncover and remember those histories of memorialisation, we must surely question our current relationship to them, and to the larger realm of myth animating them. Turning away from the land, Grimwade and those around him were vainly cementing their connection with a navigator who had neither landed in what is now Victoria nor even seen what is now called Point Hicks. •