Passing through Oatlands, in the Tasmanian midlands, my brother and I stopped at an antiques and collectibles shop in the main street. Oatlands is renowned for its Georgian sandstone buildings — eighty-seven apparently, the largest number in any village setting in Australia — but this place is not one of them. It was probably once a large general store or perhaps a haberdashery.

Undistinguished on the outside, the interior is a palace of dreams for collectors and retro lovers. Furniture, porcelain, ceramics, glassware, jewellery, ornaments, mechanical components, photographs, lamps, clocks, books, radios, tools, baubles, knickknacks and gimcracks beyond description.

My brother came away with a late-1950s Philips three-speaker valve radio in a cabinet of hand-crafted Italian walnut veneer. Worth a fortune when new, he told me, bought by the sort of people who kit themselves out with elaborate home theatre systems today.

I love to fossick but I rarely buy anything because it’s usually enough just to be surrounded by old stuff. But I stopped in front of a small wooden box full of postcards; anything with old handwriting always catches my eye. I glanced at a few. In September 1915 Auntie Daisy received birthday love from Bert and Dave. Bernard from Mangana wrote an undated card to his friend Gilbert in St Mary’s: “Have not heard from one another for a long time. How do you like your bicycle ride to school?” Fanny wrote to her Auntie Lily thanking her for the nice photo she’d sent of the twins, adding that Mother was too busy to write but would as soon as she had time.

Here was no cache of love letters or the correspondence of some august family, just snippets from the vanished lives of ordinary people.

How much for the lot? I hoped for a discount, but instead, while I browsed the jewellery and tried not to hover, the shopkeeper counted them out carefully into bundles of fifty. There were 180 altogether, and at $2 each that was $360, more than I could afford. I took fifty. I asked her to hand me any bundle but to include a couple of cards that had particularly caught my eye. Other than that, my selection was entirely random.

Most postcard collectors collect for the illustration on the front and for the age, rarity and physical condition of the cards. Messages written on the back are of minor interest unless they help date the card. Stamps and postmarks help.

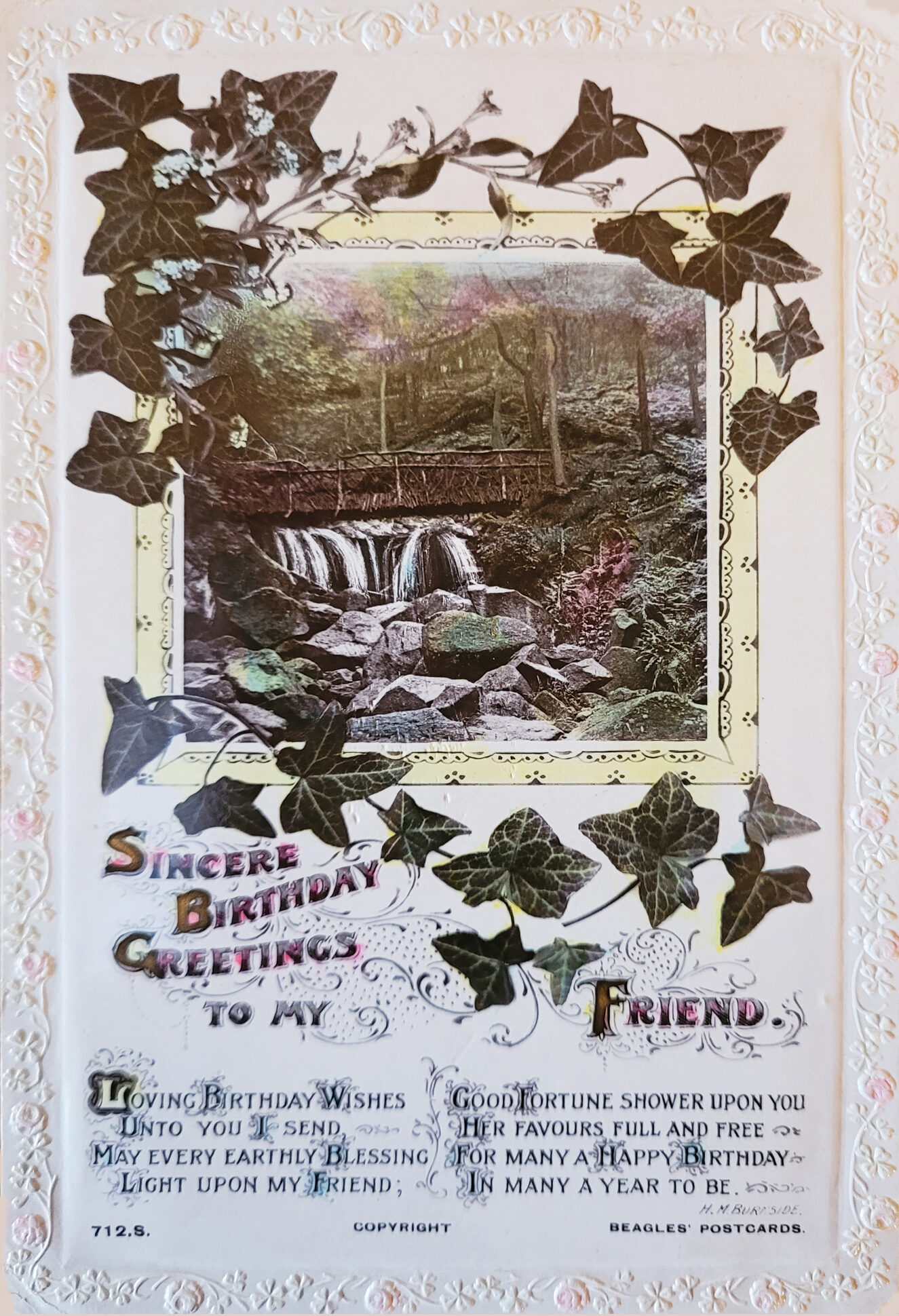

On that basis I should be feeling glum about the value of my little collection. A few are postcards sent from holiday destinations and might catch the eye of a collector, but most are greeting cards carrying illustrations of flowers, birds, cute puppies or idealised rural scenes. Most are undated but the designs suggest a decade or so either side of the first world war. Stamps have usually been torn off and some had different prices pencilled on them. Clearly, many in my set have already filtered in and out of other postcard collections.

Here were fifty uncherished leavings from lives long ended, of only minor interest to collectors and, as I have every reason to know in a thirty-year career as a historian and curator, even less to museums, libraries or archives. Context is everything. Without that, items like these carry little obvious research or evidentiary value.

So why bother? There are plenty more practical things upon which to drop $100. But fate had chucked these $2.00 memories my way and was challenging me to make something of them. For someone in my line of work, this feels deliciously transgressive. Can I coax any historical narratives out of material as meagre as this? I selected four for deeper investigation.

I started with the easiest, a postcard that had been sent to a Tasmanian solider fighting in the first world war. Unlike all the others in my set it came encapsulated in a mylar sleeve. Mylar is clear polyester film widely used by libraries and serious collectors because it is inert and will not chemically react with the material preserved in it. Obviously a collector had already noticed that an Anzac association enhances the item’s significance. (Isn’t that always the way with anything Anzacy?)

The card is dated July 1918, and reads: “Dear Fred, with hearty good wishes for a happy birthday, from your old friend, Joy.” Joy had followed the correct procedure for addressing mail to soldiers by including his service number, rank, and military unit: “No. 6373 Pte Fred Zantuck, 12th Battalion, Australian Imperial Force, Abroad.”

Old friends: Joy’s July 1918 postcard to Fred Zantuck.

This was enough information for the postcard to find its way to Private Zantuck and yet it never had a stamp, so it must have been included with a letter or parcel. This makes sense. The cost to post letters to soldiers was a shilling for every half-ounce (fifteen grams) or fraction thereof. Why spend a shilling to send a single postcard?

Thanks to Joy’s care with the address, it took me very little time to discover basic details of Zantuck’s service, and his life afterwards. Frederick Zantuck enlisted in 1916 and returned in 1919. His cousin Vernon Zantuck also served and returned. The Zantucks were a large family of German stock who had long Anglicised their name from Zantuch, and Fred’s and Vernon’s fathers had been farming in Tasmania near Colebrook for many years. There are Zantucks still living in the district.

Fred was wounded twice in 1918 by gunshot — the first time on the side of his head and the second in the chest — but on his return to Australia a medical board found he had no disability. In August 1919 he married Irene Kay of Launceston, and in 1920 they took up a soldier settlement block on land apparently surrendered by his father. He died in 1964, having farmed at Colebrook all his life save for those few years at the war. The couple appear to have had only one child, Vanda, born in 1920. Irene died in 1984.

All of these threads can be unravelled by following the clues on the postcard sent to Fred by his “old friend” Joy. But what of Joy herself? Fred cared enough to bring her card all the way home to Tasmania and keep it, but was she a school chum, a girlfriend, or a friend of one of Fred’s four sisters? Without a surname she is impossible to trace, and that is so often the way. Men who march off to war leave a far deeper imprint on the historical record than do the women they leave behind.

Next out of my three turned out not to be a postcard, but a photographic print. It is a black-and-white studio shot of a little blonde boy aged about three, seated, and dressed in shorts and knitted jumper. By his clothes I would say this was 1920s or 1930s, long past the Victorian era when small boys wore dresses.

This gorgeous little cherub is smiling slightly away from the camera but his open hands are extended towards it as if he is offering something to the viewer. His hands are also blurred: obviously the shutter fell while he was still moving. Perhaps this gesture was a convention in the photography of children at the time, but I have not seen it before.

Carefully preserved: Ernest A. Winter’s portrait of an unknown child.

On the back is no name or date, just a simple inscription in black ink: “To Dear Grand-Father, with love.” Grandfather appears to have cherished the boy’s offering because the print is in excellent condition, as if kept carefully for years in an album.

If there is no clue as to the boy’s identity, there is another path to follow. A photographer’s impression is visible in the bottom right corner of the print, and back home in Canberra with a magnifying glass and strong light, I could read it. “Ernest A. Winter, Tasma Studio.”

In no time I discovered that Ernest Albert Winter had operated a photography studio in Cattley Street in Burnie, on the state’s northwest coast. The business was advertised in the local press from 1911 until at least the mid 1950s, when it was being operated by Winter’s sons.

Winter owned the prominent building and lived upstairs. In addition to studio photography, he developed film for the public, carried Kodak supplies, and sold souvenir booklets of his own views of beauty spots around Burnie and the coast. He was secretary of the Burnie Tourist and Improvement Association and served on the local council.

I enjoyed getting to know Mr Winter, but none of it helps with the story of the little boy other than that he probably lived in the Burnie region and that his parents could afford a studio photograph of him. It was a small shock find it tossed in with a pile of postcards in a collectables shop in 2022. How could the memory of this adorable child have been discarded like that? And yet how easily it can happen. It might only take a generation or two for people to forget the names and faces of their forebears.

Finally, there is a pair of cards written from Nellie to Dora. From them we get a vivid glimpse of Nellie’s life, but blink and you miss it.

Nellie didn’t date her cards and they didn’t go through the post. One was a Christmas card published by G. Giovanardi, a postcard importer and publisher in Sydney before the first world war. Nellie wishes Dora a happy Christmas and New Year and hopes to hear from her soon. “We went to the South beach on Wednesday and had great fun. I had two swims.” Nellie is busy getting ready for Christmas and will be glad when it’s all over. “Now Dora,” she teases, “I hope you don’t eat too much pudding that day.” And she concludes, “I must now get to work again. Ta ta. Best love to all from Nellie. XXXX.”

Long journey: one of Nellie’s postcards to Dora.

Nellie covers the other card entirely with writing. Although she still enjoys making a satisfying curl on the capital letter D for Dora, she is not cheerful and excited now, she is agitated. She begins by apologising for not having answered Dora’s letter earlier but, she says, it was received with letters to Trissie while Trissie was staying with a friend, and Trissie — whoever she was — said nothing about it when she came home. Nellie had only discovered Dora’s letter that evening and it had been written the previous September. By then it was January, and Nellie had been wondering why Dora had not been writing.

“No Dora,” she continues, “Olive does not write to me now. She did not answer my letter of about 12 months ago.” Nor had Allen answered the card and letter she’d sent him the Christmas before last. “I thought you must all have been sick of me.” Still, Nellie rattles on. She is just back from short stay with Edith. Tom left that morning for Sydney, for good he says. Ella and Jean are returning to Kin after a month’s visit “down here.” She concludes by promising to write again and asks Dora to write soon too.

Fortunately, amidst all that chatter there is one contextual clue: Kin Kin is a small town in southern Queensland, northwest of Noosa. Obviously Nellie lives further south, close to the beach according to her other card. After a bit of online mucking about I established that in 1912, a couple named Charles and Ella Ferris married and settled in the Kin Kin area and that in 1934, Jean Ferris, presumably their daughter, was living with them. So, mother and daughter must have been the “Ella and Jean” who had come south to visit Nellie.

Such were the little comings and goings of Nellie’s life. Poor Nellie. Trissie carelessly (or deliberately?) failed to pass on Dora’s letter, and Dora didn’t bother to write again. Other friends have stopped writing. And just that day, Tom (a brother?) has left home, possibly for good. I’m embarrassed to have stumbled into this seemingly lonely woman’s life but fascinated as well. To try to restore lost connections, to weave scraps and fragments together into a narrative, to restore meaning: I can’t help myself, can’t not do it.

I wonder: was Nellie a spinster, one of those women we assume were washed up after the first world war with no one to marry? I recall reading somewhere that in demographic terms, the “man shortage” of the 1920s was a myth, but the loss of even a few men in a small community might have been enough to desolate the futures of the women who might have married them.

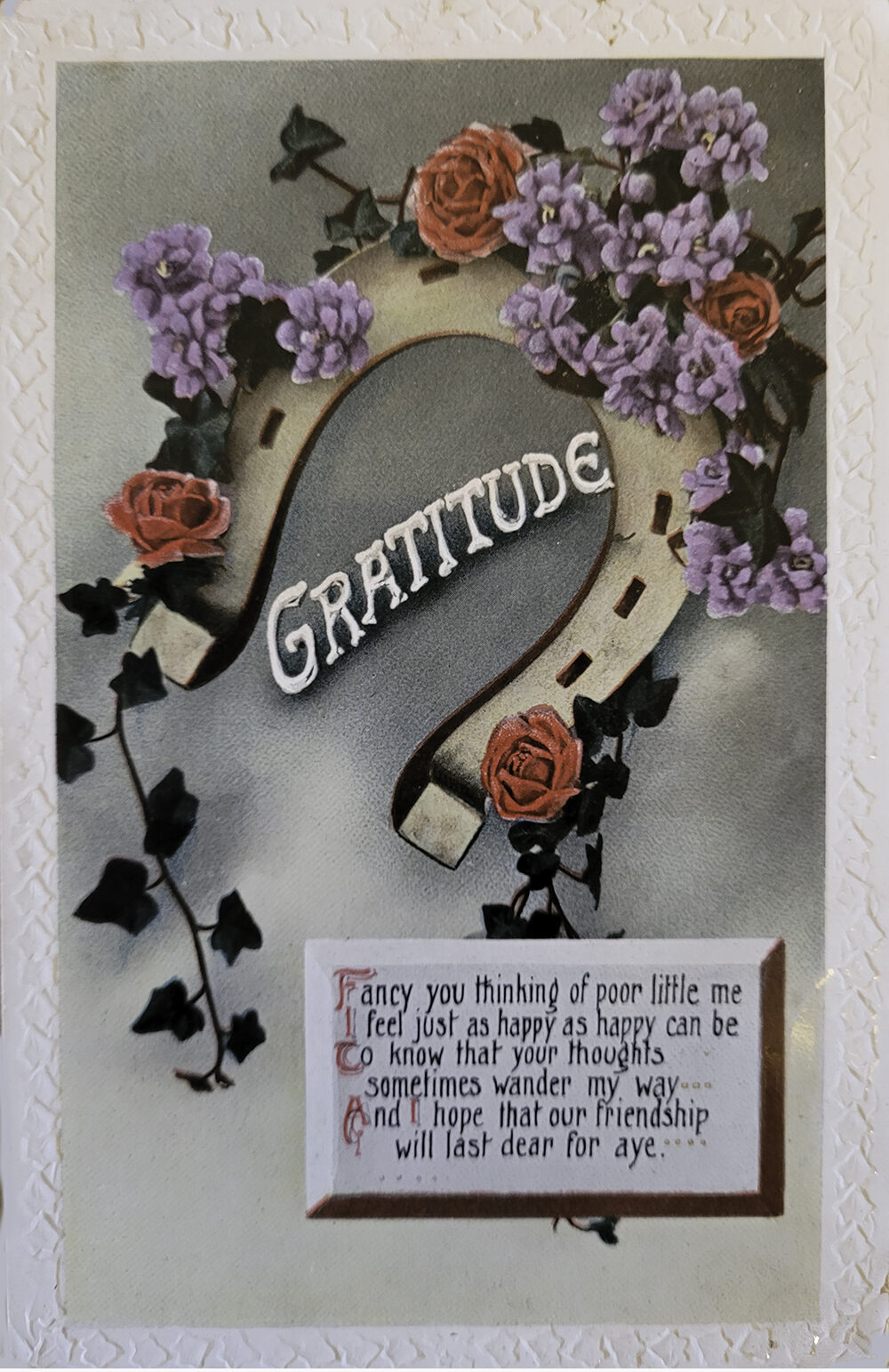

Was Nellie a frightful gossip, and would that explain why people avoided her? Perhaps. I do think she was one of life’s doormats. Look at the verse printed on one of the cards. Entitled “Gratitude,” it reads:

Fancy you thinking of poor little me

I feel just as happy as can be

To known your thoughts

Sometimes wander my way

And I hope that our friendship

Will last dear for aye.

Would Hallmark publish a card like that today? Of course not. We live in a different age, one that elevates personal growth and self-esteem because, as the L’Oréal ads tell us, “you’re worth it!” If self-pity is your issue, talk to your therapist.

Pleasingly, Dora, the recipient of Nellie’s cards and perhaps others (I chewed my lip at the thought that I’d left some behind in Oatlands) did keep them. Somehow the cards made the journey to Tasmania, brought by Dora or someone associated with her, and were preserved, or at least not thrown out, until years later when someone bundled up the cards with other unwanted stuff for a secondhand dealer to pick through. Finally, someone — me — bought them and read them and wondered what had happened to Nellie, Dora and their circle all those years ago.

I love these quiet mysteries, and history beyond the walls museums and libraries. When someone finds newspaper underneath their old kitchen linoleum, they keep it and marvel at how life was “back then.” Old bricks with makers’ marks are a great find, as is a shoe discovered in the walls of an old house, left by a builder as a lucky charm. Detectorists who find old war medals will take to the internet to find the descendants and return the medals because it feels like the respectful thing to do. Scraps of old letters used as templates in a patchwork quilt make us yearn to piece them together. Secondhand booksellers sometimes collect and share the forgotten notes and scraps they find left in books.

A Latin phrase expresses it perfectly. Ubi sunt qui ante nos fuerunt: “Where are those who were before us?” Ah, Nellie, what happened to you? •