“A rise in GST will never be popular, but we can either kick this problem down the road for future generations – by which time it will be even bigger – or deal with it now.” — NSW premier Mike Baird

Is it possible to make our tax system fairer? Yes, it is.

Is it possible to make our tax system more conducive to lifting growth and jobs, and less conducive to wasting money in speculation? Yes, it is.

Given that the federal government now spends $1.10 for every $1 it earns in revenue, is it possible to raise more revenue without harming the economy? Yes, it is.

Is it possible to carry out a tax reform that will make our system fairer and more conducive to lifting growth and jobs, while raising more revenue to reduce the deficit? Yes, it is.

But it is not going to be easy. There is no certainty that the tax reforms actually adopted will do any of these things. There is not even any certainty that there will be tax reforms: there’s no shortage of advice to the Turnbull government to drop the whole idea, from former treasurers Keating and Costello, from its own backbenchers and advisers, even from some commentators.

And you can see why. However strong the arguments for reform, no government wins votes by changing the tax system. Tax reform loses votes, as John Howard found when he scraped back in 1998 with just 49 per cent of the two-party vote. Whatever the reality, a lot of voters believe instinctively that any changes to the tax system will make them worse off. If you want to stay in government, the best tax is one that’s already there. Politically, the ideal tax policy was memorably summed up by Britain’s first and longest-serving prime minister, Sir Robert Walpole: let sleeping dogs lie. (Or, as Geoffrey Chaucer put it more poetically: “It is nought good a sleepyng hound to wake.”)

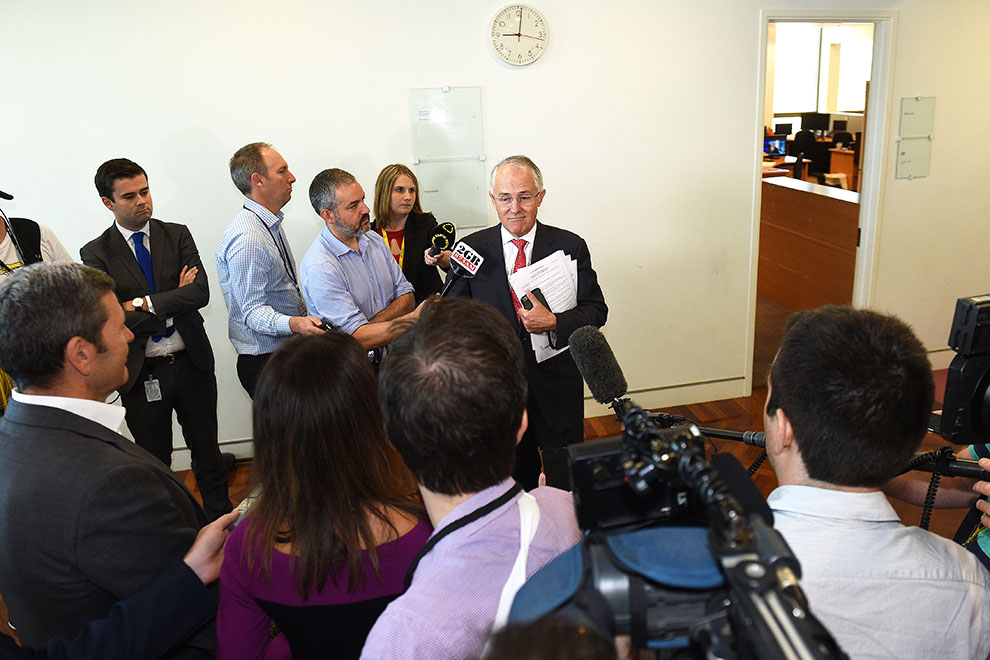

That was Keating’s attitude to tax reform after 1985; it was always Costello’s view; and on Friday morning prime minister Malcolm Turnbull highlighted the difficulties of implementing a GST rise so persuasively that journalists thought he had dropped the idea, too.

Not so, he replied immediately: “What I was trying to do was to set out what the issues are and, you know, what the criteria are by which we would judge any changes to the GST… I can assure you there are three things. We’re not going to raise more tax overall, number one. Two, any changes are going to be rigorously fair, absolutely fair. And three, you have got to drive jobs and growth.”

Importantly, Turnbull implied that the government’s tax reform blueprint would be unveiled in or with the budget in May. That was a welcome reassurance that decisions will be made and released in line with the normal processes of government, rather than held back to be sprung on us on the eve of an election. It’s good, because it gives time for debate. It also shows Turnbull’s confidence that the government will be able to win the argument.

We know from earlier reports that at this stage the government is open to either of two options: a big tax reform including a rise in the GST to 15 per cent, or a smaller one that would offer lesser income tax cuts, paid for by plugging tax loopholes such as the overly generous tax breaks for superannuation. Turnbull’s language in recent days has certainly fostered the view that he has become wary of taking on the big reform given the difficulty in selling it to a cynical electorate, and is more likely to go for a small package.

Yet a small package will deliver only small benefits, if any. A big tax reform could help us in a lot of ways: to provide more stimulus for business to invest and employ, to give young mothers more financial incentive to return to work, to realign investment incentives so that we direct more money into creating new assets rather than driving up house prices, to reduce tax rates and pay for it by plugging tax loopholes, and (with welfare reforms) to provide support where it is most needed.

Moreover, anyone who is serious about getting the budget back to surplus has to see tax reform as a central way of doing it. Frankly, people like Paul Keating and the Financial Review and the right-wing think tanks who say no, it should be done by reducing spending are just being politically correct and useless, unless they tell us what they think should be cut. The silence on that front is deafening.

The Abbott government, too, decided to close the deficit by spending cuts, and look what happened. It made huge, morally obnoxious cuts to foreign aid projects that save lives and help people out of poverty, then used the money instead to pay for its own new spending. With the support of federal Labor, it slashed $80 billion over a decade from future grants to state-run hospitals and schools, which just shifts a big chunk of its deficit to the states. And despite all that, the Coalition will still be running deficits until some time next decade.

If you are serious about repairing the budget, then you have to make tax reform part of the solution – or come up with a list of politically acceptable spending cuts that somehow have escaped the notice of all previous governments.

We don’t get many chances at tax reform. The last big reform in Australia happened more than fifteen years ago. The previous big reform happened fifteen years before that. Now, for once, enough stars in the political cosmos have aligned to make a good tax reform possible. Those who form what Ross Garnaut calls “the responsible centre” in Australian politics – whether centre-right or centre-left – should try to make the most of this chance.

It is possible now because, in Malcolm Turnbull, we have a prime minister who is highly intelligent, is well-informed on tax issues, and has a broad political base and a track record of taking bold decisions. In Mike Baird and Jay Weatherill, we have state premiers from both sides of politics who are not playing politics as usual, but have taken risks to lead the way to reforms that would deliver better policy outcomes. And, apart from federal Labor, we don’t have any wreckers trying to sabotage the process.

That makes it politically possible. What makes it politically necessary is not just the state of the federal budget – both parties seem united in denial about the seriousness of the challenges they face on that front – but the Abbott government’s decision to strip $80 billion (and vastly more than that over time) from future funding for state-run hospitals and schools.

Treasurer Joe Hockey announced those cuts with nudge-nudge, wink-wink hints that if the states asked the federal government to raise the GST to help them meet the bill, he would oblige them. Okay, in the end only two premiers were brave enough to put up their hands and ask, but the others have hardly been manning the barricades in opposition.

Unless you are innocent of political reality and think voters won’t mind if their schools and hospitals reduce services, then it is obvious that the states will need far more tax revenue in future to fill the gap, and to meet the increasing demands of ageing baby boomers on hospital and welfare services. Lifting the GST to 15 per cent is not the only option they have, but given all the debate that has taken place, it would be politically easier than opening up a whole new area of argument.

The other alternative is to raise state taxes. Land tax and payroll tax are the main options. Economists broadly agree that land tax is underused, given that land can’t be moved overseas, whereas factory and office jobs can. There’s a strong economic argument for raising more revenue from it, rather than via taxes that reduce our ability to attract (or keep) footloose investments.

But there is also a consensus that there should be a trade-off between raising land tax and reducing stamp duties on home purchase – which are seen, perhaps naively, as a major disincentive to older people downsizing into smaller homes, and to people moving interstate to find jobs. If you’re raising land tax to reduce stamp duties, you can’t also use it to pay the hospital bills.

Some economists suggest that the states could fill the gap by removing their costly payroll tax exemptions for small business. Prominent among them is Martin Parkinson, the former Treasury secretary who now heads the Prime Minister’s Department, a good man and a bright mind who keeps voicing a dangerous misconception: that payroll tax has the same economic effects as a GST.

As his former Treasury colleague Greg Smith points out, that is quite wrong. Payroll tax favours imports over domestic production; the GST treats both equally. Payroll tax favours outsourcing and non-labour inputs over employment of workers; the GST treats all factors of production equally. Smith, now chair of the Commonwealth Grants Commission, told a recent tax conference at the Australian National University, “Payroll tax is probably a lot more distorting (to efficient production) than most of our models suggest.” He suggested it be replaced by a tax on business cashflow.

There is no good alternative, which is why the states need a higher GST; the premiers who have remained on the sidelines have shown a distinct lack of courage. But while they need more revenue, the Turnbull government has locked itself into promising that tax reform will not be used to increase revenue.

Somehow Turnbull and treasurer Scott Morrison have to square that circle. Mike Baird’s option, which he envisages as a short-term fix, would see the Commonwealth raise the GST to 15 per cent but keep the additional revenue. Most of it would be used to compensate households through income tax cuts and higher welfare benefits, some to cut company tax, and some to give the states an extra $7 billion over three years to keep the hospitals afloat and implement the Gonski school reforms.

That deal would last only three years, leaving open the question of what a higher GST would be used for in the long term. Sensibly, Baird has concluded that there is no consensus possible on that question at this point, and it would be better to sideline it until a GST increase has been shepherded through.

Weatherill’s plan is bolder, including the extension of the GST to cover financial services. (The GST now applies to less than half of all consumer spending, greatly undermining its supposed virtue of applying neutrally to all spending, across the board.) He proposes that the GST be raised to 15 per cent, and that the Commonwealth takes a third of that (all the new money, that is) and gives the states a fixed 17.5 per cent of federal income tax in return. He would like to trade a share of the GST for a share of income tax, whose revenues have been rising faster than GST revenues because those areas exempted from the GST (health, education and so on) now account for most of the growth in consumer spending.

But the prevailing view now is that neither plan will be adopted. The Australian’s Newspoll this week found that 54 per cent oppose a rise in the GST to 15 per cent, even with compensation, and only 37 per cent support it (with 9 per cent uncommitted). In his heart, Malcolm Turnbull is one of the 37 per cent; but while he is brave, he is not foolhardy.

Yes, Mike Baird won the NSW election last March despite his unpopular promise to privatise the state’s electricity assets, but despite Labor’s efforts that was not the central issue of the campaign; Baird made himself the central issue, and won handsomely. A rise in the GST is much more of a kitchen-table issue, and hence more dangerous; Turnbull would rather have a campaign in which he and Bill Shorten were the central issue.

That doesn’t rule out all tax reform. The same Newspoll found overwhelming support for reining in superannuation tax breaks for high-income earners, as Labor has proposed; but that would not raise much, unless the Turnbull government undertakes a much more thorough overhaul of superannuation tax breaks. The government would need to look beyond that to raise the funds to cut income tax and company tax by appreciable rates.

Many would argue that the most destructive tax break is negative gearing – restored by Keating in 1987 on the specious grounds that its removal was causing rents to rise. As Saul Eslake has since pointed out many times, the rent rises were confined to Sydney and Perth, “and that was because in those two cities, rental vacancy rates were unusually low (in Sydney’s case, barely above 1 per cent) before negative gearing was abolished.”

This tax break has inexorably eroded Australia’s traditional pride in being a society in which ordinary people own their own homes, and is gradually replacing it with a landlord-and-tenant culture. We now have about 1.5 million investors – three times as many as we had twenty years ago, let alone thirty – who claim to be running their rental investments at a loss, and hence deduct the losses against their tax on other income. It is a colossal misdirection of household investment, which, as economist Stephen Anthony points out, should be employed to create new assets, not simply transfer ownership of existing ones.

No government can undo what Keating did, but Turnbull and Morrison do have two good options. First, they could shut the gate; all existing negatively geared investments could be grandfathered, but no new ones allowed. Over time, the damage would gradually subside, house prices would stabilise and become more affordable, and investment would be directed where it would do more for growth and jobs.

Second, they could limit the damage. The average tax loss claimed by rental investors is about $10,000 a year; only those with incomes over $100,000, and those who claim to have no net income, claim bigger losses than that. The government could limit the losses allowed on existing investments to $10,000, or $15,000 or even $20,000. That would impose a cap that protects the interests of the small investors the Coalition sees itself as representing, but stops the tax break being used for large-scale rorting.

Doing anything on tax has its risks. That’s why governments in the past have chosen, in Mike Baird’s words, to “kick this problem down the road for future generations,” with the problems getting bigger all the time. We now have a window of opportunity to fix at least some of the problems. One hopes Malcolm Turnbull and his team will mix some boldness with their prudence. •