Imagine a country in which a government of the centre-right decided to make it a top priority to tackle inherited disadvantage. Where much of its limited new spending is devoted to “social investment” to reduce deprivation and increase workforce participation. And where it’s chalking up impressive results.

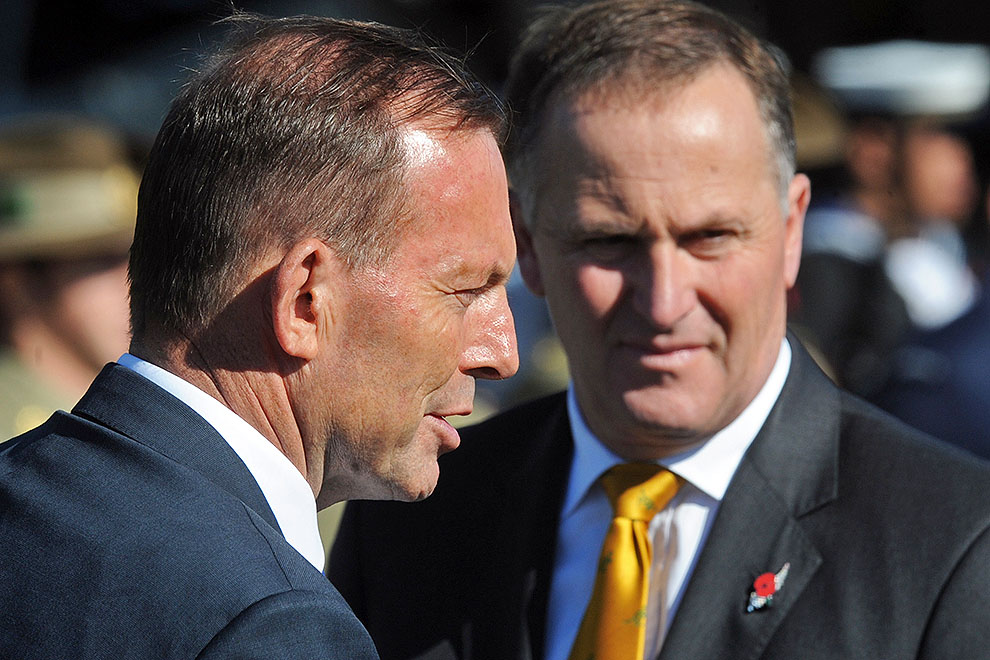

You don’t have to go far to find it – just across the Tasman. Taking on disadvantage is rarely a priority for conservative governments, but it has become an increasingly important theme of the second and third terms of the National Party government under prime minister John Key.

Last week finance minister Bill English took it further, bringing down a budget in which generally tight control of government spending contrasted sharply with increased welfare payments aimed at reducing the number of children growing up in hardship, especially among the least well-off New Zealanders (largely Maori), who are dependent on welfare, and often in and out of jail.

Why? John Key himself grew up on welfare, in public housing in Christchurch with his sisters and widowed mother Ruth, a Jewish refugee from Austria. While he rose to become head of global foreign exchange trading for Merrill Lynch before entering politics, he has never forgotten where he came from. In his first speech as National Party leader, in 2006, he declared, “You can measure a society by how it looks after its most vulnerable… It is in the interests of no one, and to the shame of us all, that an underclass has been allowed to develop in New Zealand.”

Bill English, whom close observers see as the main generator of the government’s ideas, came to politics as a young conservative Catholic who had been a Treasury economist, then a farmer in the remote Southland. He has grown into a formidable independent thinker, committed to balanced budgets, small government, rebuilding earthquake-damaged Christchurch, and increasing business opportunities – but also to creating a society that intervenes to help its most vulnerable back into the mainstream.

Key, English and other ministers have combined humanitarian instincts with actuarial logic to create a world-leading experiment: investing heavily to reduce the risk of children inheriting their parents’ welfare dependency, and to offer incentives and intensive help for the parents themselves to get off welfare and into work, and then stay in work.

What is most remarkable is that Key and English have made this “social investment” a top priority, in part, as a business decision to reduce the long-term cost of government. Moreover, they have invested in trying to lift up those at the bottom at the short-term cost of another of their top priorities: to get the budget back in surplus.

Some right-thinking Australian newspapers told us last year that New Zealand’s budget was back in surplus; no it isn’t, not the way they measure it. But although the shortfall embarrassed Key’s government at budget time, it has little or no economic significance. On the Australian government’s definition of a surplus, English’s budget for 2014–15 will certainly end up in surplus. On the definition used by most Australian states, he was already in surplus in 2013–14.

For four years, Key and English had promised to deliver a surplus in 2014–15. But it tells you something about them and their government that when New Zealand’s dairy prices crashed last year, and near-zero inflation slashed the expected tax growth, English flatly rejected the temptation to make sudden spending cuts, raise taxes or fiddle the figures just to get over the line. At the budget launch last Thursday, he declared, “Knee-jerk responses are not a hallmark of this government, and we will maintain spending that is supporting families, driving better public services and helping economic growth. Those matter more than the actual date we reach surplus.”

To Australian eyes, this is an unusual government. It has its faults, certainly, but even political foes concede privately that in seven years in office, Key, English and other ministers have chalked up an impressive record of competence, confidence and consistency, and exhibited a progressive streak that differentiates them from their Australian cousins. They have legalised gay marriage, set up an emissions trading scheme (albeit a tokenistic one), and initiated this new scheme to identify where best to target programs and spending to lift people out of welfare and poverty.

English described it to Inside Story as “using an insurance approach to crack welfare dependency… A lot of government spending is trained on a relatively small part of the population whose lives are…” he paused, “complex for them, and expensive for us.” Targeted interventions aimed at lifting them out of dependency and into productive working lives not only improve their lives, he said, but also dramatically reduce government spending in the long term. “What works for the community works for the government’s books.”

To get the budget back in surplus, departments and agencies receive no increase for inflation, forcing them to find their own savings, and then bid for the small amount of new spending dubbed “operational allowances” – in 2015–16, just over NZ$1 billion a year. English argues that this discipline has forced departments to stop measuring their success in terms of getting more money out of government. “They’ve realised that the changes they need are to understand how they can make a difference to the lives of the families they’re there to serve.”

He told Key’s biographer, John Roughan:

The fundamental driver of the government’s budgetary costs is social dysfunction… If we stop a prisoner reoffending, we save $90,000. If we have a group of seven- to nine-year-olds who are going to cost $750 million by the time they turn thirty, we need more health checks, healthy homes, social workers in schools. John [Key] has created permission for a centre-right government to talk about public services positively.

Key has set his government specific targets: to reduce long-term unemployment, achieve near-universal infant immunisation and early childhood education, reverse the rise in child abuse, and sharply reduce the rates of school dropouts and prisoners reoffending. The government issues regular progress reports, and they are surprisingly blunt about where it is falling short.

In earlier budgets, English shut down tax breaks to free up funds to achieve these goals, and froze childcare subsidies to pay for new childcare services in disadvantaged areas. Last year, with an election to win, the new spending was less targeted, but it included free doctors’ visits and prescriptions for children under thirteen, and a revamp of the country’s minimalist paid parental leave scheme to more closely match Australia’s.

Last week’s budget continued English’s trademark austerity to grind down real spending in order to get back in surplus in 2015–16. Spending is forecast to rise just 2.5 per cent next year, making 8.5 per cent in four years. Yet it also included a sizeable “child hardship package” of heavily targeted new spending. In one hit, it increased the benefit for families on welfare with dependent children by NZ$25 a week – inflation adjustments aside, the first such rise for forty years. It raised tax credits for the working poor by up to NZ$24.50 a week, and upped childcare subsidies for low-income families from NZ$4 to NZ$5 an hour.

The hardship package was focused particularly on “children at risk”: those kids whose parents are long-term welfare dependents and have family problems and criminal records. At the budget launch, English said actuarial assessments based on longitudinal studies have found that among children growing up in such families:

• 75 per cent will not complete school;

• 40 per cent will themselves become long-term welfare dependents by the time they’re twenty-one; and

• 24 per cent will have been jailed by the time they’re thirty-five.

Children growing up in this group, English said, cost taxpayers an average of NZ$320,000 by the time they turn thirty-five; some cost taxpayers more than NZ$1 million. These are stunning figures, which he uses to persuade fellow conservatives that it is in society’s interests to give these children and their parents a priority on spending that they have never had before.

The new spending came with a bite: people on benefits will be expected to look for part-time work once their youngest child is three. Perhaps it is more bark than bite: officials assured us that no parent would be thrown off benefits if they cannot find suitable work. It was met with silence from the government’s friends, vociferous opposition from its enemies.

It is not only the most disadvantaged that the Key government is trying to lift up, but also low-income groups more broadly: sole parents, the working poor, and low-income families on benefits – again, with the goal of getting them out of social and economic exclusion and into the workforce. English says their monitoring is already showing lower rates of child abuse, sharply improved workforce participation by the target groups, a 38 per cent reduction in youth crime, a 40 per cent fall in teenagers on sole parent benefits, and a closing of the gap between immunisation rates of Maori and Pakeha (whites).

The policy grew partly out of a pair of reports written four years ago that emphasised the importance of early intervention to prevent at-risk children and young adults from falling into failure that would cost themselves and society dearly in the long term. As critics point out, New Zealand has a long way to go. Its six-year whirlwind of free market reforms from 1985 to 1991, including a 20 per cent cut in welfare benefits, redesigned all the rules to favour those at the top. The New Zealand Council of Christian Social Services quotes data showing that over thirty years, real per capita incomes almost doubled for the top 1 per cent, but rose only 14 per cent for those at the bottom. New Zealand has fewer than a million children, but it is estimated that 260,000 of them are living in poverty.

The council’s executive officer, Trevor McClinchey, warily supports the government’s approach. “It’s a sensible model,” he told Inside Story. “From our perspective, it makes a great deal of sense to invest in people, and to prioritise spending according to need. If people are unwell, to invest in them to make them well, and train them to work, it’s a good process.” But he warns that the needs are many, and the increasing delivery of services by for-profit providers is seeing welfare services become another commodity. “It should be more about how you provide a more equitable environment for families to live successfully – employment, wages, making this a better place.”

McClinchey also warns that New Zealand’s robust job growth – 80,000 new jobs in the last year, with unemployment tipped to fall below 5 per cent next year – may be driving some of the gains the government attributes to its policy changes. The real test will come if and when the economy starts going backwards. Unemployment among the Maori and Pacific Islanders is now down to a relatively low 12.5 per cent (among whites, it is 4.5 per cent). The government is forecasting four years of solid, if slower, growth.

Labor’s finance spokesperson, Grant Robertson, is also cautiously supportive of the social investment push. “There are elements in it that I think might be useful – particularly early intervention,” he says. “Creating children’s teams from different agencies is a very good idea, as is the evidence-based approach. But the implementation of it has been under-resourced. A true investment approach would invest in developing people’s abilities and skills more broadly.”

Others are harder to please. On the day after the budget, a group of protesters tried to storm the Auckland Convention Centre, where Key was speaking to a post-budget lunch, complaining that the new money was not enough, that it was all going to families, that the individual jobless were left out. A representative of one group called it “a mean trick” designed to fool New Zealanders into thinking that their government is really trying to tackle child poverty.

No one I spoke to shared those doubts. These guys are serious about getting people back into the mainstream. Whether or not they can do it, they have started down a path that will show future governments around the world how to start closing the poverty gaps that years of ideology and indifference have opened up. •