It’s twenty years since John Howard launched Australia’s policy of sending boat-borne asylum seekers to Nauru and Papua New Guinea’s Manus Island. Australia has since detained almost 6000 people there, many of them for years. By some estimates, the policy has cost Australia $26 billion. As this milestone approaches, one question from Behrouz Boochani, a Manus refugee whom Australia rejected and New Zealand accepted, has never seemed more relevant: “What has Australia truly gained?”

Howard introduced his “border protection” regime on 29 August 2001, after the Norwegian freight ship Tampa had rescued 433 Afghan asylum seekers from a sinking vessel in the Indian Ocean. Arne Rinnan, the Tampa’s captain, asked to land them on Australian territory. With an election pending, and his Coalition government trailing Labor in opinion polls, Howard ordered forty-five Australian SAS soldiers to board the Tampa and thwart Rinnan’s bid.

Within days, the government had struck deals with Nauru and PNG to host Australian detention camps. The hapless Tampa refugees became their first inmates, and later boatloads entering Australian waters were sent there too. Howard called his action the Pacific Solution.

Labor closed the offshore camps in 2008 after Kevin Rudd defeated Howard, only to open them again four years later. For both sides, the political justification was that this harsh regime would deter more “boat people” from risking the journey. But Madeline Gleeson, of the Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law at the University of NSW, says, “We’ve been mired in this policy for so long for purely political reasons.”

Indeed, to many Australians its sheer longevity suggests that offshore detention has always been this country’s way of dealing with asylum seekers. But the policy is facing its own crisis, and apparently crumbling from within, with no sign of a fresh, more humane and less expensive approach from either main political party.

In late June I travelled to Albion Park, south of Sydney, for a different milestone — one that offered an insight into how Australia once reacted to boat arrivals.

About 250 people had gathered at the HARS Aviation Museum to mark the fortieth anniversary of the Australian navy’s rescue of ninety-nine Vietnamese asylum seekers on 21 June 1981. Known as the “MG99” (for “Melbourne Group”), they were among millions of people who fled Vietnam and neighbouring countries after the end of the Vietnam war in 1975. Some started arriving on Australia’s shores in 1976, with more over following years, giving Australia its first experience of dealing with boat-borne refugees. Another Liberal, Malcolm Fraser, was prime minister at the time.

The contrast with Howard’s approach could not have been more striking. Claire Higgins of the Kaldor Centre explains it: “The immigration department considered several ideas, but the Fraser government rejected the options of turning back boats and potentially indefinite immigration detention, because they would be inhumane, damaging to Australia’s international reputation and would not provide a lasting solution for people forced to flee.” Higgins says Fraser government decision-makers recognised that such options were “harsh and ill-conceived from the start.”

Australia also worked with the UNHCR, the United Nations refugee agency, in a bid to find a genuine regional approach, and with other resettlement countries such as the United States and Canada. Australia admitted over 65,000 refugees from Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia over seven years to 1982, many from regional refugee camps.

“There was a sense that Australia and America had a moral duty to do something because we’d been involved in the Vietnam war,” says Madeline Gleeson. “We also had political leadership then of a kind that we haven’t had for a long time.” Fraser had his opponents within the governing Coalition, but his policy prevailed.

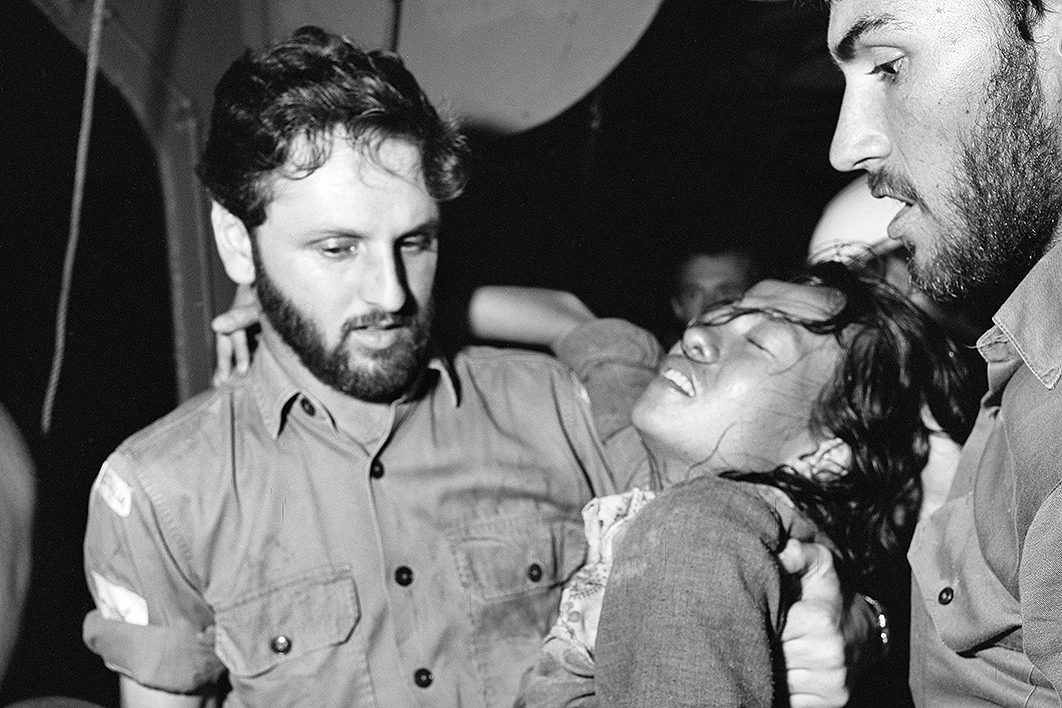

On military exercises in the South China Sea in June 1981, the Royal Australian Navy aircraft carrier HMAS Melbourne rescued the MG99 refugees after a Tracker surveillance aircraft spotted their leaking boat. All ninety-nine, including nineteen children, were hauled safely up the side of the vessel at night. The ship landed the refugees in Singapore, where UN and Australian officials processed them in a refugee camp. The Melbourne asked the Fraser government to resettle seventy-seven. They arrived on a Qantas flight in Australia a month after their rescue.

At the Albion Park anniversary, former navy people involved in the rescue, and some of those they saved, made speeches. The Tracker aircraft that found them rested near the stage as a museum exhibit. The late Mike Hudson, then commander of the Melbourne, was recalled as saying, “The MG99 rescue was the highlight of my career.” The contrast with John Howard’s use of military commandos on the Tampa twenty years later was sharp.

Stephen Nguyen, aged twenty when he was rescued, later told me how his life unfolded in Australia. “It wasn’t easy at first with barriers of language, loneliness and no relatives,” he said. “For my generation it was very hard.” He taught himself English, worked in factories and started a food shop business in western Sydney so he could support younger siblings who followed him to Australia.

Two of those siblings became doctors, another an electronic technician. Another brother later worked for the State Library of NSW. Nguyen now has four children, three of them at university.

The first boat arrivals from Vietnam and neighbouring countries were assessed for refugee status in Australia. Then, under an international agreement struck to handle the continuing flow, the UN refugee agency assessed them in camps in Hong Kong, Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines for resettlement in the West — avoiding their need to risk perilous journeys by boat that later claimed many lives.

I asked Nguyen his view of Australia’s offshore policy, under which people have been detained indefinitely. He paused. “You can’t treat them as prisoners, as abandoned people,” he said. “To me the offshore policy is a horrible policy. You have to treat people like humans, and to make the screening process faster in a humanitarian way. The Tampa story has tarnished Australia.”

Where does the Tampa policy stand after twenty years? Government figures show Australia sent 1637 asylum seekers to Manus Island and Nauru in the seven years between when Howard opened the camps in 2001 and when Kevin Rudd’s Labor government closed them. Despite Howard’s claim that the Tampa drama was about keeping “boat people” out, most were resettled in Australia and New Zealand.

Another 4180 people have been sent to the offshore camps since Julia Gillard’s government reopened them in late 2012, making a total of almost 6000 people detained in both places. When Rudd usurped Gillard briefly as prime minister before the 2013 election, he sought to out-tough the Coalition by declaring that no island detainees would ever settle in Australia. And when Tony Abbott won the election, he out-toughed Rudd, reverting to Howard’s militarisation of asylum policy by creating Operation Sovereign Borders and using the navy to turn back boats.

Australia hasn’t sent detainees to the islands since 2014 — mainly, it seems, because boats have been turned back and some asylum seekers have been deported to their countries of origin. Many others have been quietly transferred to Australia for medical help and to remove children from Nauru. They’ve been left in detention centres here or on six-month bridging visas in the community, with no indication of where they’ll end up, or when. A Senate committee was told in March that this group could number more than 1200. Another 137 asylum seekers are still in PNG and 123 in Nauru. Onshore or offshore, the government sticks to its line that they will never settle in Australia.

But if island detainee numbers have fallen, the policy’s financial cost has only soared. Governments have kept secret the precise burden on Australian taxpayers, but parliamentary and think tank researchers have assembled credible figures from budget papers and other sources. They paint a staggering picture.

Madeline Gleeson told Britain’s House of Commons home affairs committee late last year that offshore processing at a “conservative estimate” costs Australia roughly $1 billion a year. Building camps in such remote places, outsourcing their management (often without adequate cost controls) to private companies, and funding charter flights and healthcare are just some of the costs. Australia also pays Nauru visa fees of $2000 per refugee per month, bringing total visa costs to $26 million in 2016–17 alone.

Gleeson says offshore processing’s real cost “consistently exceeds” government projections. In 2017–18, it cost Australia $1.5 billion, more than twice the estimate of a year earlier. Even with smaller offshore numbers, the government forecast spending $1.2 billion on offshore processing in 2020–21.

The government’s undisclosed legal fees, defending challenges to its treatment of asylum seekers, would inflate the bill even more. Last March the Australian Lawyers Alliance sent a freedom of information request for claims lodged by and compensation paid to asylum seekers for wrongful detention and personal injury in Australia, PNG and Nauru over the decade to 2021. It asked for similar information on personal injury applications by detention centre staff. The home affairs department claimed it had no relevant documents in its possession.

Drawing on costings by the consultancy firm Equity Economics, a 2019 report by the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre, Save the Children and GetUp! estimated that offshore detention and processing had cost $9 billion between 2016 and 2020. It built on an earlier report by Save the Children and UNICEF that estimated offshore processing and boat turnback costs of $9.6 billion between 2013 and 2016.

Even allowing for the onshore detention component of these figures, they suggest that the offshore policy cost taxpayers the best part of $19 billion from 2013 to 2020. Assuming Gleeson’s conservative estimate of $1 billion a year also applied to the Pacific Solution from 2001 to 2008, the offshore policy appears to have cost Australians about $26 billion, in both its versions, since 2001.

The psychological cost for detainees kept offshore for years is bad enough. But could Australia have also saved money with a different approach?

The 2019 report argues it could. It calculates that keeping asylum seekers offshore costs $573,000 per detainee per year. If asylum seekers were dealt with more speedily in Australia instead, the costs would fall sharply: to $346,000 per detainee in onshore mandatory detention per year, and to $10,221 a year for each detainee living in the community on a bridging visa. The report calls the cost of keeping people offshore since the Pacific Solution restarted in 2013 “enormous both economically and morally.”

Apart from the 1200 or so people the government has transferred to Australia from Manus and Nauru, about 30,000 asylum seekers who arrived by boat during the last years of the former Labor government are still living in Australia. Coalition governments have called them the “legacy caseload,” banning them from lodging visa applications for up to four years and receiving legal aid. They can’t apply for permanent residency, just for three- or five-year temporary visas. The UN Refugee Agency brands these as “punitive measures” imposed “largely for political reasons.” Australia, it says, could be violating its obligations under the 1951 Convention on the Status of Refugees.

Abul Rizvi, a former deputy secretary of the immigration department, argues that these people are unlikely to be deported. “I think the present government’s policy is just to ignore them,” he says. “That’s bad policy. Australia had always had a just policy that if you were in Australia you’re either on a pathway to permanent residency or to be sent back if you’re not eligible as a refugee. Ignoring them is more American policy.”

Then there’s what Rizvi calls a “fifth wave” of asylum seekers who started arriving about six years ago. These people aren’t brought by people smugglers; they arrive by air on visitor visas. Typically from Malaysia and China, they then apply for asylum through agents here and overseas who’ve arranged their trips; this gives them work rights, usually on farms, while they wait. Rizvi estimates about 27,000 such people whose asylum applications have been refused are still in Australia, and growing at about 500 a month. He says the applicants are being exploited by employers and agents, and some have probably been injured, or even died, but their plight is rarely reported. Rizvi calls this wave a “scam” and “the biggest asylum seeker wave we’ve ever had.”

Taken together, the “legacy caseload,” the “fifth wave,” the transfer to Australia of detainees from the islands, and the release of asylum seekers who were brought to Australia for medical treatment under the repealed medevac law sends a message about a government that once boasted credentials of “strong border protection” and never allowing “unauthorised” arrivals in.

Rizvi’s conclusion is damning. “I’d say our borders have never been more permeable and never managed so badly than under Scott Morrison and Peter Dutton [the former home affairs and now defence minister],” he says. “The borders are being used by scam organisers of the fifth wave. And the medevac releases show the government has given up. It knows these people aren’t going to leave.”

Labor under Paul Keating’s government pioneered detention centres onshore. But Rizvi speculates the offshore policy that Howard started with Tampa would not have happened under other postwar leaders, including Robert Menzies, the Liberal Party’s founder: “If this question had been put to Menzies he’d have found a different pathway to residency for those who’re eligible. He was much more conscious of social cohesion, as were Bob Hawke, Malcolm Fraser and Paul Keating.”

One political notion has largely driven Australia’s offshore policy: refuse people on boats entry to Australia. The problem with such a narrow approach is that it eventually leaves governments stranded. As Madeline Gleeson of the Kaldor Centre points out, it has no “exit strategy”: what to do with people once they’ve been found to be refugees.

At times, governments have desperately tried to find a way of dealing with these people caught in limbo. The Abbott and Turnbull governments struck deals with Cambodia and the United States respectively to take refugees from offshore camps. Just seven in Nauru agreed to resettle in Cambodia, at a reported cost to Australia of $55 million; four later returned voluntarily to their countries of origin rather than stay there. A Senate committee was told in March that 890 refugees have been resettled in America. That country, not Australia, now benefits from the initiatives that newly settled refugees like the MG99 group usually bring to immigrant countries.

Since the Taliban’s taking power in Afghanistan, the United States, Britain, Canada, Germany and others have signalled plans to take in thousands of Afghan refugees. So far, the Morrison government seems to be sticking to its line that Afghans on temporary visas in Australia should stay that way. Marise Payne, the foreign affairs minister, says they won’t be asked to return to Afghanistan “at this stage.” Such an approach is mired in the past. The crisis is bound to trigger more boat refugees from Afghanistan, and it should challenge the government to emulate the Fraser government’s response to another humiliating military finale, in Vietnam.

Gleeson thinks that the offshore detention policy is winding down by default. “It’s been winding down slowly since 2014, the last time new boat arrivals were sent offshore,” she says. “It’s an admission by the government that it’s not a long-term policy, and that it’s never going to work. It was meant to deter people from arriving by boat, but it didn’t.” •

Updated 18 August 2021 to reflect changed circumstances in Afghanistan.