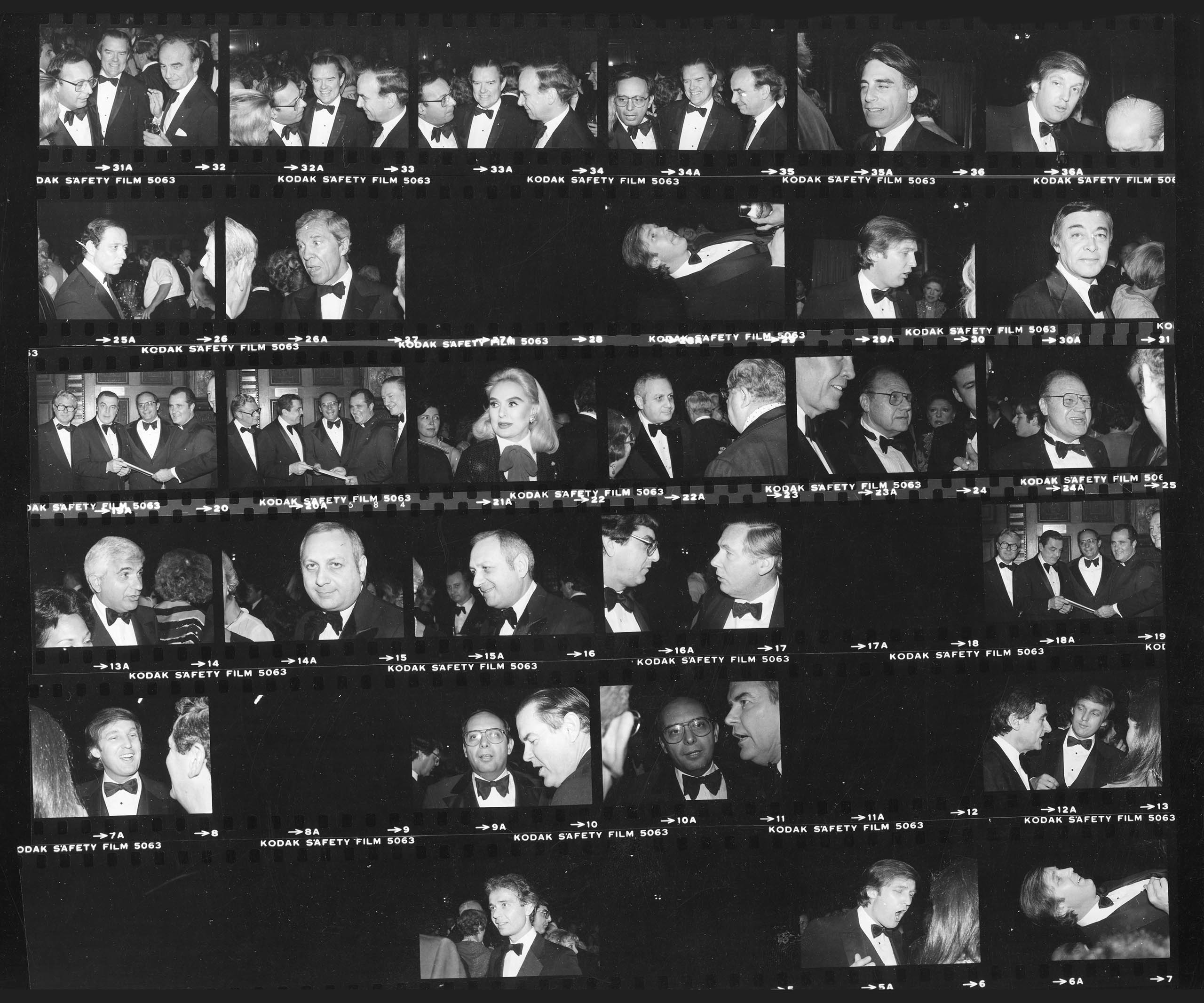

For Rupert, it almost certainly wasn’t love at first sight. When Donald Trump became an acquaintance, probably in New York and probably in the early 1980s, the shameless, publicity-hungry property developer was keen, like his fellow wannabe celebrities, to be covered in Murdoch’s New York Post.

Trump’s business reputation was already far from pristine. He and his businesses would eventually be party to a total of more than 4000 legal actions, exceeding all other leading property developers combined. He would file for bankruptcy — for himself or various of his entities — no fewer than six times. When he was divorcing his first wife Ivana, he planted news stories designed to humiliate her, some of which made the front page of the New York Post and estranged him for a time from his three eldest children.

Over the decades after their first meeting both Murdoch and Trump became better known and more influential. Murdoch’s founding of Fox News in 1996 gave him a much higher national profile; its chief executive for the first twenty years, Roger Ailes, a man who combined heavy involvement in Republican politics with a strong background in television, quickly built the network into a force on the national political scene. On NBC, meanwhile, Trump had huge success with his fifteen-season reality TV series The Apprentice, which launched in 2004.

Once Barack Obama became president, Trump was given a Monday morning call-in slot on Fox News’s Fox and Friends: “Bold, brash and never bashful,” the promo proclaimed, “the Donald now makes his voice loud and clear every Monday on Fox.” It was in that slot that he baselessly propagated the “birther” claim that Obama wasn’t American-born and was therefore ineligible to be president. In just two months during 2011, Fox devoted fifty-two segments to Obama’s “foreign birth”; and in forty-four of these the claim went completely unchallenged.

At some point Rupert and his third wife Wendi became friendly with Trump’s daughter, Ivanka, and her husband Jared Kushner, whom Murdoch helped mentor. In 2015, though, when Ivanka told Murdoch that her father was truly going to run for president, Murdoch “dismissed the possibility out of hand,” journalist Michael Wolff writes in his 2023 book, .

Nor in the early days of Trump’s candidacy did the relationship run smoothly, at least in Trump’s eyes. At the first debate among Republican contenders in August 2015, hosted by Fox, one of the network’s most prominent anchors Megyn Kelly asked Trump about his misogyny: “You’ve called women you don’t like ‘fat pigs,’ ‘dogs,’ slobs and disgusting animals.” When Trump responded after the program with a similarly nasty and misogynist attack, Ailes stayed silent and his deputy Bill Shine directed other anchors not to speak up for Kelly. Fox News PR eventually issued a single statement in her defence.

Rupert was more forthcoming. Trump was getting “even more thin-skinned,” he tweeted, adding that “friend Donald has to learn that this is public life.” A few months later, in February 2016, Trump accused Fox of not wanting him to win and Murdoch of rigging a survey of voters. “Time to calm down,” tweeted Murdoch, adding that if he was running an anti-Trump conspiracy then he was doing a lousy job.

Despite his complaints, Trump was receiving much more coverage than the other Republican candidates on Fox News. He and Ailes were in close touch throughout the primaries, and the network fell loyally in behind Trump’s candidacy once it was clear he was going to be the Republican nominee.

Even up to the election, according to Wolff and other observers, the relationship was unequal. At his post-victory party Trump “was on tenterhooks waiting for Murdoch,” writes Wolff. “‘He’s one of the greats,’ he told his guests… ‘the last of the greats. You have to stay to see him.’” Murdoch seemed to be in shock when he eventually arrived, “struggling to adjust his view of a man who, for more than a generation, had been at best a clown prince among the rich and famous.”

Ailes, who had seen the relationship up close, told Wolff that Trump “would jump through hoops for Rupert. Like for Putin. Sucks up and shits down. I just worry about who’s jerking whose chain.” Later, Ailes said that he and Trump “were really quite good friends for more than twenty-five years, but he would have preferred to be friends with Murdoch, who thought he was a moron — at least until he became president.”

Although he was more favourably disposed towards Trump than many others, Ailes had few illusions about his capacities: “Donald? He’s Richie Rich. He’s richer than you but he’s not smarter than you — in fact, he’s clearly a dumb motherfucker, I say with all due respect. He is so dumb. But smart is what people hate.” Two weeks before his death, Ailes observed that Trump “won’t have any idea how to run the government, nor care, but he knows how to pull every fucking string in television.”

Trump’s elevation to the presidency created a unique relationship with Fox News. In Wolff’s words, “The Trump White House was a Fox White House.” Researching his book Hoax: Donald Trump, Fox News, and the Dangerous Distortion of Truth, journalist Brian Stelter identified twenty people who moved from Fox News to the White House between 2017 and 2020.

Initially the Fox–White House relationship was one of mutual convenience, possibly containing some degree of personal admiration. Murdoch and Trump, who were in frequent phone contact, each put their own gloss on it. “Murdoch, who had never called me, not once, was now calling all the time,” said Trump, while Murdoch complained that he “couldn’t get Trump off the phone.”

Many at Fox News had direct personal relations with many at the White House. Perhaps the most interesting was between Trump and Sean Hannity, a Fox News anchor who had long been Trump’s “go-to guy at Fox.” They were on the phone almost every day — so much so that Wolff describes Hannity as “Trump’s closest confidant, his chief adviser.” Trump lavished public praise on Hannity, one night even claiming on air that he had postponed a call to Chinese president Xi Jinping in order to talk to him.

Trump’s relationship with Fox News was unique in another way, too. He spent more hours each day watching the network than any previous president spent looking at TV, and seemed to rely on it for information more than on his officials’ briefings. One night in February 2017, Trump made a seemingly bizarre comment about Sweden that flummoxed Swedish officials. It turned out that Tucker Carlson’s Fox News program had featured an obscure conservative filmmaker pushing the idea that a Swedish crime wave was being fuelled by lax immigration policies. It was a self-affirming feedback loop of misinformation.

Trump “grew more and more intolerant of any accurate reporting on Fox and raged against the reporters,” writes Stelter. “For Trump it was never enough. Rupert recalled that Trump once told him, of Fox, ‘You’re 90 per cent good. That’s not enough. I need you 100 per cent.’ Rupert claimed that he replied, ‘Well, you can’t have it.’”

In 2020, with Murdoch now living in semi-isolation in England to minimise his risk of catching Covid-19, the telephone relationship all but ceased. When Trump played down the risks of the pandemic, Stelter writes, Murdoch warned him to take it seriously: “You better be careful, it’s a big deal.” Well, Trump responded, “some people say that.”

Fox supported Trump strongly in the 2020 election, but the relationship was on a downward trajectory. A bizarre moment in the developing conflict came on the night of the 2020 election when Fox News’s “decision desk” was the first to say that Joe Biden had won Arizona. The call provoked an enormous and puzzling controversy. Before the election, Fox News had joined with Associated Press in developing what they thought were better ways of projecting outcomes. According to the journalists directly involved, this was what allowed them to be first on the night. But their call provoked extreme anger in the White House, which urged Fox to reverse it, and also among many Fox viewers, who saw it as a betrayal.

The fact that the call proved to be accurate was no defence. What should have been a triumph for Fox was seen even by their own management as an embarrassment. Two months later, the two journalists most directly involved no longer had jobs at Fox.

In The Fall Wolff says that Trump saw the Arizona call as “the tipping point in his relationship with Fox. Murdoch, he understood, not without justification, was out to hurt him.” This is a nonsensical proposition at several levels. Most basically, Murdoch was not involved in the call and only learnt of it after it had gone to air. The ongoing disputes overlook the fact that the call had no substantive impact: voting had finished, so no votes were affected and nor was the counting of votes.

Wolff makes Murdoch’s disillusion with Trump abundantly clear. At various times, he called Trump an “asshole,” an “idiot,” a “fool,” “plainly nuts,” and someone “who couldn’t give a shit,” “had no plan,” “just wants the money,” is “crazy, crazy, crazy” and “a loser.” “Of all Trump’s implacable enemies,” writes Wolff, “Murdoch had become a frothing at the mouth one.”

Rather than give reasons for Murdoch’s views, Wolff seems sometimes to regard them as symptoms of senility. “A close Murdoch confidante…,” he writes in The Fall, “described Murdoch’s loop of Trump obsession as possibly ‘early dementia-like.’ Murdoch could not get off the subject.”

The reasons for Murdoch’s disenchantment were substantial. He was appalled at Trump’s incompetent and irresponsible response to the Covid-19 pandemic. He didn’t believe Trump’s claims about a rigged election. (As early as 8 November, an editorial in his New York Post urged Trump to stop the stolen election rhetoric.) And, like many others, he was outraged by the attack on the Capitol on 6 January 2021 and by Trump’s encouragement of violence. Soon after the attack, Stelter reports, Murdoch told Fox Corp board member Paul Ryan that he wanted to make Trump a non-person on Fox.

But Murdoch found that divorcing Trump was much more difficult for Fox News than his own divorce from Jerry Hall. Trump’s continuing court cases and his pre-eminence in Republican politics made it impossible for Fox to treat him as a non-person. Moreover, Murdoch encountered considerable internal resistance. Hannity, one of the network’s biggest stars, exclaimed, “Fucking no Trump… You want to tell me what Fox is without Trump?,” and, on another occasion: “There’s only one reason I’m here now and that’s to protect Donald Trump.”

Murdoch’s stated wish also ran directly against his top management’s concerns that ratings would plummet if they did not fall in behind Trump. This obsession with ratings meant that short-term considerations were always paramount. The cynicism and evasions of Fox News’s senior managers was eventually exposed by Dominion Voting Systems’s legal suit against the network.

As the primaries for the 2024 election loomed, Murdoch’s early embrace of Ron DeSantis turned into a disaster. The Florida governor’s credentials as a culture wars protagonist were strong, and some saw him as Trump without the baggage, but he instead proved to be Trump without the charisma, or the populist touch, or the support.

Trump, now near-unchallenged within the Republican Party, was not inclined to kiss and make up. He boycotted Fox’s staging of debates and mounted a stream of invective against them. Privately he was scathing of Murdoch, who at ninety-two had just announced his fifth marriage. “Only one reason why: prove you can still fucking do it even though everyone knows you can’t,” he claimed. “It’s a fake news marriage.”

I should conclude with a confession. After Trump’s victory in 2016, I wrote an article for Inside Story, most of which covered Fox’s performance and problems in the lead-up to the presidential campaign. I finished by suggesting that Trump’s election could be a pyrrhic victory for Fox. I noted how the network’s ratings declined during George W. Bush’s presidency, especially in its final year, and suggested that if and when Trump’s political fortunes fell, Fox News would also be in trouble.

I was wrong. I was still focused on the old mainstream media and the old politics. I severely underestimated how successfully Trump could shift the blame for his multiple failures, at least to the satisfaction of his core supporters. Nor did I fully grasp just how niche-driven Fox’s programming strategy had become. Its ratings were not sensitive to shifts in mainstream opinion; rather they relied on keeping faith with Trump’s core.

How will the Murdoch media approach the 2024 election, and what role will its ninety-three-year-old “semi-retired” “chairman emeritus” play? Trump’s dominance of the Republican Party means that many of its candidates and apparatchiks have to face a loyalty test by embracing the lie that the 2020 election was stolen. With one party strongly committed to a baseless fiction, the election presents unique challenges for all the news media, but especially for a network whose ratings are tied to whether it satisfies Trump’s constituency.

No doubt Rupert was and is keen to divorce Donald, but Trump looks likely to get custody not only of the Republican Party but of Fox News as well. •