In the early 1980s, bands like Duran Duran, Spandau Ballet, Adam and the Ants and the Human League were at the forefront of a second “British invasion” of the United States, rivalling the one led by the Beatles two decades earlier. It seems all the more odd, then, that it should be so hard to say what the New Romantics’ music consisted of.

It’s not a problem with other music of the era. We all know what punk rock was. We know what ska and reggae and soul and disco were. But New Romanticism is harder to define, at least musically, because it was more an attitude than a style. Perhaps that is why, in Dylan Jones’s 680-page book, Sweet Dreams: The Story of the New Romantics, he enlists a multitude of voices to help him work it out.

It started in the late 1970s, was all over by about 1985 and its middle name was flamboyance — unless it was pretension, or possibly petulance. It was certainly visually striking, but whenever you try to say something about the music itself, you end up talking about the look of the thing. That look — eighteenth-century ruffles and tricorn hats when it wasn’t warpaint; brightly coloured coats and wide-brimmed fedoras when it wasn’t business suits and quiffs — was part of the bands’ success, especially in the United States, where, as Jones points out, the nascent MTV loved these British acts.

Musically, though, it is easier to say what New Romanticism wasn’t than what it was, and even then there are paradoxes. The New Romantics’ music wasn’t ska or reggae, though with his soulful vocals on “Red Red Wine” and “Many Rivers to Cross,” UB40’s Ali Campbell staked a claim to be counted in their number; it wasn’t soul, though what was Boy George if not a soul singer? And what was Annie Lennox, who would go on to duet with Aretha Franklin? New Romanticism wasn’t disco either, yet consider, for a moment, the muscular synth-pop syncopation behind the chorus of the Human League’s “Don’t You Want Me.” Above all, it wasn’t punk, with its loud, fast, three-minute, two-chord rants; and yet, in a way, it had more in common with punk than anything else.

The debt to punk is something Dylan Jones nails down quite quickly. As with the punks, their successors were all about dressing up and posing. The clothes might have been brighter, cleaner and less torn, the pose more a sulk than a sneer, but New Romanticism was as much an attitude as punk ever was. And punk’s primary impresario was there, too: fresh from grooming (if that’s the word) the Sex Pistols, Malcolm McLaren was taken on by Adam Ant to give him and his band a makeover. In a typical burst of wild imagination, McLaren suggested Adam dress as a “dandy highwayman” and sing his songs to an imitation of tribal drumming from Burundi. Then (and this was equally typical of McLaren) he made off with both Adam’s money and his band, added a thirteen-year-old girl, Annabella Lwin, who’d been discovered working in a laundromat, and named the new group Bow Wow Wow. He even gave them the Burundi drumming idea.

Bow Wow Wow’s first single, released on cassette and called, somewhat self-reflexively, “C•30 C•60 C•90 Go,” certainly sounds like punk — short, shouty and monotonous — but the imagery McLaren devised for the band was something else. When the band’s first album came out, it had the outlandish title See Jungle! See Jungle! Go Join Your Gang Yeah! City All Over, Go Ape Crazy, but its cover was beyond outlandish. In emulation of Edouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, the band members picnicked on the grass, young Annabella naked and meeting our gaze, like the woman in the painting. Even at the time, the image raised eyebrows — today it would be unthinkable — yet the significance of the cover was the band’s borrowing from nineteenth-century French art. This was no longer the world of the Sex Pistols.

But if punk was the New Romantics’ immediate precursor, maybe even their catalyst, earlier models were closer to their aesthetic. David Bowie was certainly one. He makes the cover of Jones’s book, flanked by Boy George and Lennox, Adam and Sade, he contributed to the music of the New Romantic years — first with Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps), then the critically underrated Let’s Dance — and he carried on for three more decades.

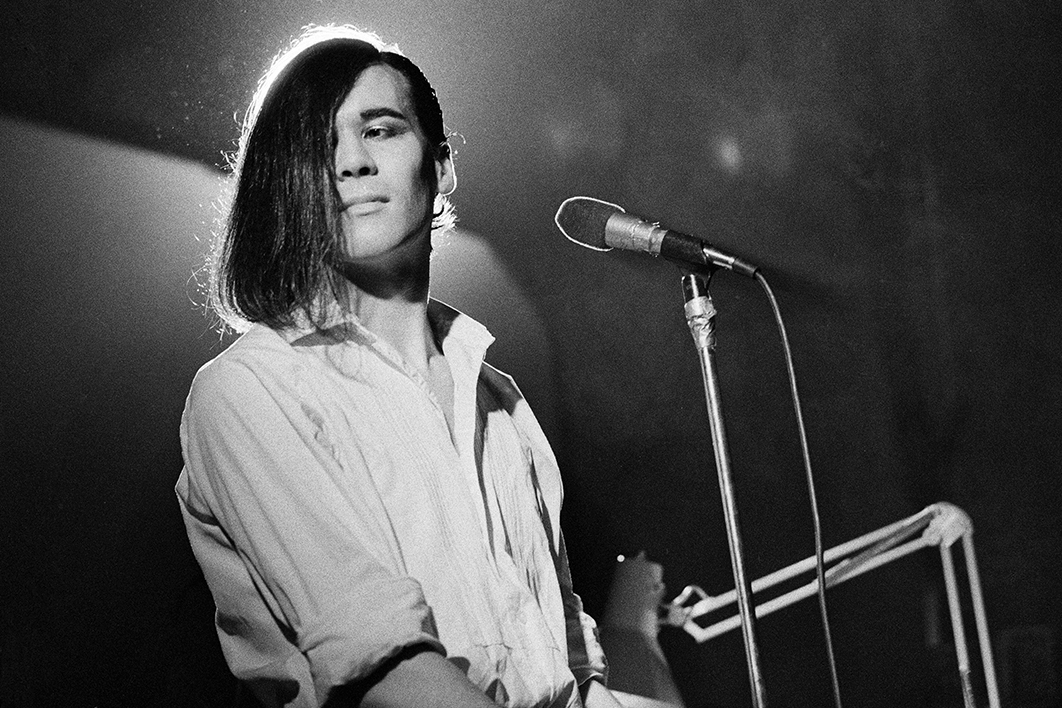

Bryan Ferry was another. Peter York, one of Jones’s talking heads, says of Roxy Music’s “Virginia Plain” that Ferry’s voice was “the natural antithesis of Joe Cocker.” Here was “a singer whose whole approach said, ‘I’m not singing, I’m being a singer.’” Ferry’s example was taken to heart by the likes of Tony Hadley, Simon Le Bon and Midge Ure, their bands (Spandau Ballet, Duran Duran and Ultravox) even donning Ferry’s suits and ties from time to time.

The other singer we might mention in this context was Marc Almond of Soft Cell. Jones describes this duo as a mixture of glamour and squalor, which nicely sums up their biggest hit, “Tainted Love,” but Almond’s singing on that most touching of revenge songs, “Say Hello, Wave Goodbye,” is oddly heroic. The elongation of “me” — such an unlikely word and such a hard sound to draw out — in the line “Take your hands off me” is all the more affecting for Almond’s 90 per cent accuracy.

Almond was also very obviously gay, and never before in pop music had queerness in general been so celebrated. Part of it was men dressing as women — admittedly this sometimes went little further than an elaboration of the pantomime dame trope — and women as men. Annie Lennox and Sade’s buzz cuts were as much their trademarks as their magnificent voices were (and if you’ve forgotten what genuinely great singers some of these figures were, you could do worse than start by listening again to Lennox’s wild vocal arabesques on Eurythmics’ “There Must Be an Angel (Playing with My Heart)”). But Pet Shop Boys, Bronski Beat and Frankie Goes to Hollywood had no need of cross-dressing or androgynous looks. They wore their pride in their music.

The echt New Romantic song? I’m going for “Don’t You Want Me,” which is not only catchy as hell but also involves perhaps the best story of the era. The Human League was a moderately successful electro trio, a sort of worthy version of Kraftwerk, when in 1980 its two best musicians, Ian Craig Marsh and Martyn Ware, departed to form Heaven 17. Left behind was singer Philip Oakey, who was responsible for fulfilling the commitments of a Human League tour, only days away. He spotted two schoolgirls dancing together in a Sheffield nightclub and thought they looked the part. (The parallels with Annabella Lwin’s discovery in a laundromat are uncanny.) Susan Sulley and Joanne Catherall had never sung or danced professionally and hadn’t heard of the Human League, but there and then Oakey invited them to join his tour, which they did with their parents’ permission.

Following the tour, the two of them had to go back to school, but the following year were then signed up as full-time members of the band, together with new musicians to replace Marsh and Ware. The band wrote new material and began putting out singles. After their third single in a row made the Top 20, they cobbled together an album, Dare. Wanting to cash in, the band’s manager suggested releasing a fourth single from it. Oakey was reluctant to put out “Don’t You Want Me,” which he regarded as atypical, but was eventually persuaded. By Christmas, it was number one, where it remained for five weeks, the biggest-selling UK record of the year.

It’s a pure pop story and a pure pop song, and the song might as well be about the story:

You were working as a waitress in a cocktail bar

When I met you.

I picked you out, I shook you up

And turned you around,

Turned you into someone new.

Oakey explains in Jones’s book that the song was misunderstood: “For some reason people think ‘Don’t You Want Me’ is a love song, and it’s not. It’s a power song.” But it’s also a song about the times, about image and artifice, about “not singing, but being a singer.”

And here’s a curious thing. Until this moment, many critics had refused to take this music seriously, in spite of — or more likely because of — the popularity of some of it. But both Dare and “Don’t You Want Me” — the New Romantics’ commercial zenith — were surprisingly well reviewed.

As Jones puts it in his book, “Here was a record you could hear in Woolworth’s as well as in a nightclub, something you might hear on both John Peel [the radio DJ famous for playing new, hard-edged, often experimental music] and daytime Radio 1, a walk-you-through-my-story song that moved a banal domestic to-and-fro up onto the big screen. This was the perfect New Romantic macro/micro-riposte to the genre’s previous tropes of isolation and elitism. You could sing along with it too. The object, after all, was ultimately success.” •