As architecture, Josh Frydenberg has designed a pretty good budget. It injects some stimulus into an economy that needs it, focuses new spending in areas that matter, rejects the temptation to provide a big cash splash, and sets up the budget for a credible surplus at last.

So it’s a shame that the best of the six budgets under this Coalition government will probably be irrelevant. What the treasurer spelt out last night will become reality only in the improbable event that his government is re-elected.

The bookies reckon there’s only a one-in-five chance of that. On average, they give Labor an 80 per cent chance of winning next month’s election, and the Coalition just 20 per cent.

As for the opinion polls, every one of the thirty-three polls Wikipedia records since Scott Morrison became prime minister has shown Labor ahead, on average by a commanding 53.5 per cent to 46.5. Indeed, Wikipedia records 150 polls by Australia’s established pollsters since September 2016 — and Labor has led the Coalition in every one.

This suggests that last night’s effort was not the real 2019–20 budget. That one will probably be brought down in July by Labor’s treasurer, Chris Bowen, for a new government that will leave a very different imprint on Australia’s choices.

Frydenberg’s budget will probably end up as a first draft for what Bowen will deliver in July. Where there are no important differences between the parties, the details announced last night will hold. But many of them will be swept away — in some cases, fortunately so.

Why? Because Frydenberg’s quality architecture was not matched by his government’s sense of decor. There are some terrible policies here.

A prime example? Try the $2 billion — that’s $2 billion of our money, folks, as well as a further $2 billion from Victorian taxpayers — that the Morrison government wants to spend on building a very fast train line between Geelong and Melbourne. Why build a VFT there? Because the Liberal Party has a marginal seat, Corangamite, at one end of it.

The federal government has already committed a breathtaking $750 million to duplicate eleven kilometres of Corangamite’s rail line between South Geelong and Waurn Ponds. The business case for the main part of the project found it would return only 60 cents benefit for every $1 spent on it. And the government has pledged to fund stage three of the project, duplicating Geelong’s rail tunnel, without even waiting for a business case.

Pork-barrelling? That understates it. This is misuse of funds on a colossal scale: taking $2.75 billion of our money to try to save one marginal seat. Some would call it grand larceny.

This budget is full of soft corruption like this, by which the government takes our taxes and uses them for Liberal and National party electioneering. For example, the daily ads for the government’s infrastructure spending, which the Guardian says are costing us $250,000 a day. And another spotted in passing: the budget commits to upgrade six commuter car parks at Melbourne suburban stations — not the federal government’s job — and they are all in endangered Liberal electorates: Goldstein (two), Deakin (three), and Aston (one).

Enough: you get the picture. Your taxes are being rorted. Let’s return to the architecture.

Frankly, this is not the budget we were led to expect. The headlines suggested it would be a great cash splash. Yet since Christmas the government has committed just $4.6 billion of net new spending for the eighteen months to mid 2020. That increases its planned spending by just 0.6 per cent — partly because the government has pledged to spend $632 million to repair damage from the North Queensland floods.

The other areas of new spending in that year and a half are mainly in health and aged care ($858 million), transport projects ($700 million), the royal commission into abuse of people with disabilities (almost $200 million) — and the Energy Assistance Payment ($284 million), which is basically a cash handout to people on welfare.

In an unexpected twist this morning, the energy payment became the first budget decision to be changed. Frydenberg used a post-budget interview on AM to announce that the handout will also go to people on the dole, even though his budget papers said the opposite. One suspects his hand was forced after a government representative airily defended the exclusion by implying that people on the dole were unemployed by choice.

Look carefully at the table on pages 49–51 of the budget’s expenses statement and what stands out is the austerity of their spending plans. The so-called efficiency dividend lowers spending in each area by 1.25 per cent a year unless the government decides otherwise. And in almost half the areas the budget covers, it plans to spend less in three years’ time — even in nominal terms — than it does now.

The areas facing cuts include parliament itself, foreign aid, pharmaceutical benefits, arts, culture and even sport, primary industry, immigration, aviation, miscellaneous welfare programs, public order and safety, government superannuation benefits, and administrative costs across the board.

All those areas will have their nominal spending cut during a period in which we can assume population growth of 4 to 5 per cent, and inflation of 6 to 7 per cent. Even more areas will experience cuts to their real spending per head — so that, if they can’t find ways to transform how they work, they will have to reduce services, and in many areas, significantly.

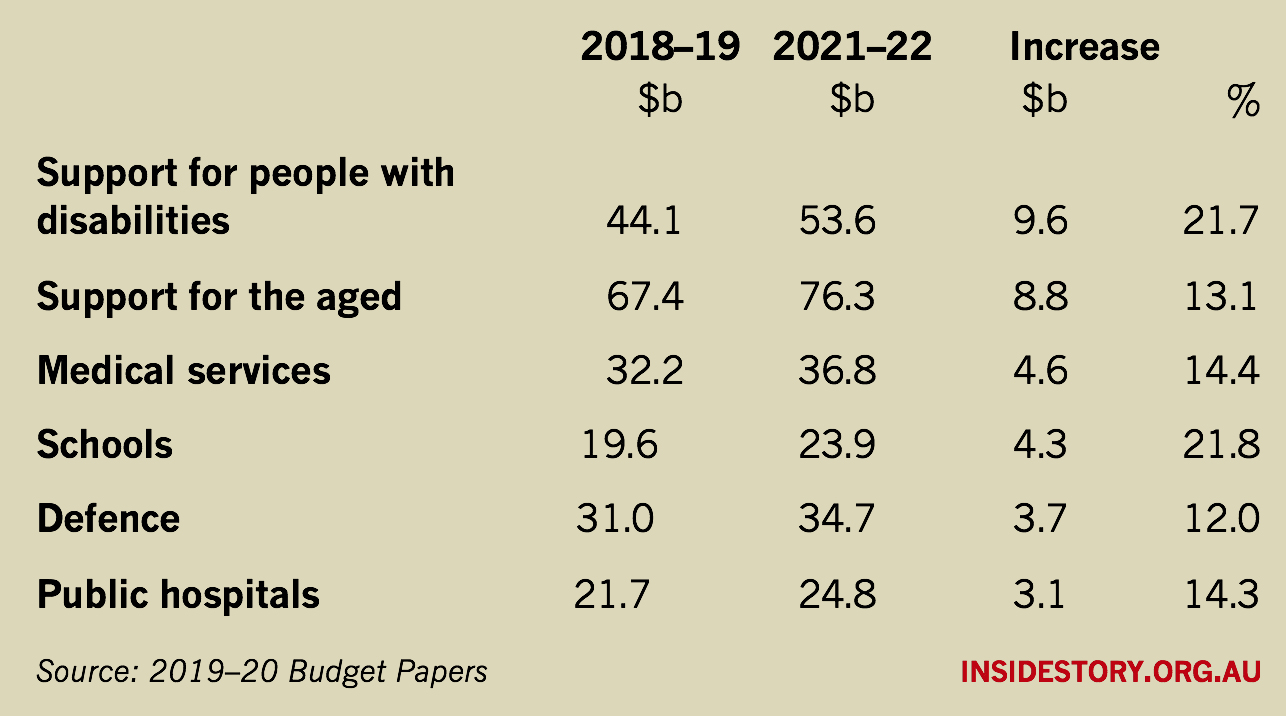

By contrast, in the next three years most of the growth in spending will be in just six areas:

The tax handouts are even more modest: they’ll cost just over $1 billion over the same eighteen months. Most of that comes from a new end-of-the-year tax handout, the Low and Middle Income Tax Offset, first announced in last year’s budget. Its maximum level will roughly double from the original plan to $1080 — a significant amount to a battling family — with most taxpayers receiving some payout.

That’s millions of people, yet the government estimates the cost of doubling the handout will be just $750 million, or about 0.15 per cent of its annual revenue. That looks surprisingly low. But only those earning between $48,000 and $90,000 would receive the maximum offset, and Grattan Institute figures imply that they make up only roughly a third of all taxpayers. Those earning less than $48,000 or between $90,000 and $126,000 will get lesser sums.

A second tax change will provide short-term stimulus: the tax break allowing small business to immediately write off capital spending against tax will be expanded to cover medium businesses, and spending of up to $30,000. But Treasury expects only modest use of that until next year.

The big tax cuts lie ahead, in 2022–23, which is beyond the election after next, and again in 2024–25, just before the election after the election after next. You would think that after the Howard–Costello tax cuts in 2007 blew a hole in the budget, our politicians would have learnt not to legislate for big future tax cuts until we know we can afford them. Nope: even the Centre Alliance senators buckled under pressure to vote these ones into law.

The second and third stages of those tax cuts are very regressive, so this year Frydenberg has tried to provide something to those on lower and middle incomes. If the Coalition is re-elected, the key changes would be:

• The top threshold for the 19 per cent (low) tax rate would rise from $37,000 to $45,000 from mid 2022.

• The 32.5 per cent (middle) tax rate would be reduced to 30 per cent from mid 2024. By then, under the tax changes passed last year, that rate will apply to all income in the range of $45,000 to $200,000. That was a huge step towards the right’s dream of a flat income tax. It is a regressive change that Labor will struggle to undo.

Labor will unveil its own tax cuts tomorrow night. And if it wins the election, as most assume, they will be the ones that matter.

The make-up of the new Senate will be crucial to one key question: will Labor be able to enact its plans to halve the capital gains tax break and limit negative gearing to newly built properties? When the crunch came last year, South Australia’s Tim Storer was the only crossbencher to hold firm against government pressure to vote for the big tax cuts. But others like the Alliance senators and Derryn Hinch must have realised that this could rebound badly on us.

By contrast, Frydenberg’s budget this time is almost reticent in its modesty. Despite the government apparently heading for electoral defeat, its tax cuts amount to only 0.2 per cent of tax revenue. That is a surprise, and a relief to those who believe that constantly running up debt is a bad strategy, for governments and households alike.

We have had false surplus predictions before — Wayne Swan recklessly claimed in 2012 that the budget would be in surplus from then on — but this one looks real. The short-term budget forecasts it is based on were described by ANZ bank economists today as “reasonable… even conservative.”

Treasury may be a little optimistic in forecasting that growth will accelerate in the year ahead to 2.75 per cent (roughly average for the years since the global financial crisis), with household spending growing by the same amount. But it is also forecasting that unemployment will flatten at around 5 per cent, jobs growth will slow, and wage growth will continue rising on its current trajectory.

The forecast budget surplus of $7.1 billion allows some room for error. The economy could grow more slowly than Treasury expects, endangering the surplus. If you think running a surplus doesn’t matter, consider this: we have had eleven years straight of budget deficits, under both sides, and they have lifted gross government debt from $55 billion to $560 billion, and taken us from $40 billion of net assets to $373 billion of net debt.

Global interest rates are at or near record lows, yet we are now paying $17 billion a year in interest — almost as much as the federal government spends on schools or hospitals. Deficits provide valuable support when an economy slumps, but they are not something we should rely on in normal times. After eleven years of deficits, it matters that we repair the damage to our finances — with eleven years of surpluses, we must hope, and substantial ones.

But the medium- and long-term outlook for the budget is not good. On budget eve, the nonpartisan Parliamentary Budget Office put out a sobering document trying to forecast how much damage our ageing population will do to the federal budget. It concluded that within a decade, the ageing of the baby boomers will worsen the budget balance by $36 billion a year through lower workforce participation, superannuation tax breaks, and the costs of aged pensions, healthcare and aged care.

We could also be facing higher interest rates. China’s economic stability is more precarious than it seems. The rivers of gold flowing into the budget from higher mineral prices have helped lift company tax revenue by almost half in three years, from $68 billion in 2016–17 to an estimated $99 billion in 2019–20. That is the main reason why we have moved from deficit to surplus — but we know that those revenues can recede as fast as they can surge.

One of the subtler fine points of this budget’s architecture was that it chose to be conservative in estimating future mineral prices. Frydenberg and his team could have made the budget outlook appear rosier, and used that to justify spending more, had they followed past practice and assumed that current prices will last. They put their long-term credibility ahead of any short-term fix.

That’s wise in political as well as economic terms. People don’t believe politicians any more. They want to see the budget back in the black, and they want to see problems demonstrably fixed. Promises have been dishonoured too many times to be worth much now.

One last point. The doyen of budget commentators, Chris Richardson of Deloittes, pointed out in the Financial Review this morning that the combination of tax changes announced in the past year will amount to more than $8 billion of tax cuts from 1 July. That’s equivalent, he argues, to a 2 per cent increase in the typical after-tax wage — and much of it will be coming as a lump sum. Many households are under pressure, and bad debts are rising, so some of that will be saved — but a lot of it will be spent, and soon.

Moreover, if Labor wins next month’s election, its plans to restrict negative gearing to newly built properties from 1 January are almost certain to trigger buying by some investors to get in first, so their properties are “grandfathered” by that date and immune from Labor’s tax changes. That will inject new demand into property markets, and hopefully reduce the glut of unsold properties that has been dragging down housing prices in Sydney and Melbourne.

The Reserve Bank has left itself little room to move interest rates now when it needs to. But the markets expect at least one rate cut ahead, maybe two. That might affect property markets more than business investment, but it’d be worth it.

Add the three potential stimuli together, and it’s plausible that the economy might move up into a higher gear — say, from second to third — as 2019 rolls on.

This budget is not an election winner: no budgets are anymore. But it won’t hurt the government’s chances, and could improve them. Finally, after six years, we are in sight of the balanced budget Tony Abbott promised us back in 2013. •