Pedder Dreaming: Olegas Truchanas and a Lost Tasmanian Wilderness

By Natasha Cica

University of Queensland Press | $59.95

WHEN I was very young, we lived in the foothills of Mount Wellington, high above Hobart. One of our neighbours was Olegas Truchanas. We moved away after a few years – fortunately, as it turned out – but Truchanas’s roots grew deep into the hill. He had arrived in Tasmania in 1949 from Lithuania, following an extraordinary escape from the grip of Russian dominance, and re-established his life by joining a circle of Hobart artists, starting a family and building a house on a bush block in West Hobart with a superb view over the Derwent estuary. He spent the working week in the central Hobart office of the Hydro-Electric Commission, Tasmania’s state within a state. And in his free time he explored Tasmania’s southwest by foot and home-made kayak, often solo, photographing its wild places. From the mid 1950s, he began presenting public slide shows of Tasmania’s south west, drawing large crowds and winning the Hobart Mercury’s recognition as a talented “New Australian.”

Lake Pedder was a favourite destination, a place where Truchanas and his family camped and Hobart’s artistic salon convened for many summers. The jewel of Tasmania’s southwest, Pedder was first mapped in the 1830s; by the end of the nineteenth century it was being spruiked as a tourist drawcard. A walking track was cut through soon after, and the first light plane landed on its magnificent quartzite beach in 1946. Despite this, Truchanas felt that few Tasmanians were aware of the lake’s majesty or prepared to defend it in the face of an uncompromising political vision of hydro-industrialisation. Despite Pedder’s inclusion in a national park in 1955, the Hydro soon began investigating the catchment’s potential for power generation, and in 1967 state parliament legislated the lake’s destruction.

Truchanas once asked his friend, the Hobart artist Max Angus, for a painting of Lake Pedder. As Angus retells it, “He said to me one day, ‘I want a dream of Lake Pedder. Anybody can take a photograph.’” That request, with its portent that future generations might only dream about the lake, frames the narrative of Natasha Cica’s superb Pedder Dreaming: Olegas Truchanas and a Lost Tasmanian Wilderness.

Truchanas was born in 1923. A keen sailor, he was chosen for Lithuania’s sailing team in the 1940 Tokyo Olympics, but war and the occupation of his homeland by Soviet troops dashed his Olympic hopes. When his family fled Lithuania for Germany, Olegas remained behind to participate in resistance activities. He was reunited with his parents and sister at the end of the war but travelled alone to Australia as a displaced person. After a stint in Bonegilla Migrant Camp, he settled in Tasmania, serving his two-year labour contract with the Australian government in Hobart’s Electrolytic Zinc Works. His family joined him in Hobart.

Truchanas’s dangerous life had taken a psychic toll. One of his earliest Tasmanian friends recalls him looking nervously around when they first went bushwalking. Soon, though, he was at home in the rugged Tasmanian landscape. He climbed Federation Peak in 1952, in what was possibly the first solo attempt, and a few years later kayaked from Lake Pedder to Macquarie Harbour, navigating the Serpentine and Gordon rivers. Strahan residents were astonished to see the small kayak heading towards the wharf, propelled by wind in a makeshift sail, Truchanas steering with a cord attached to his toe while he reclined with a book. The kayak is now a prized part of the National Museum of Australia’s collection.

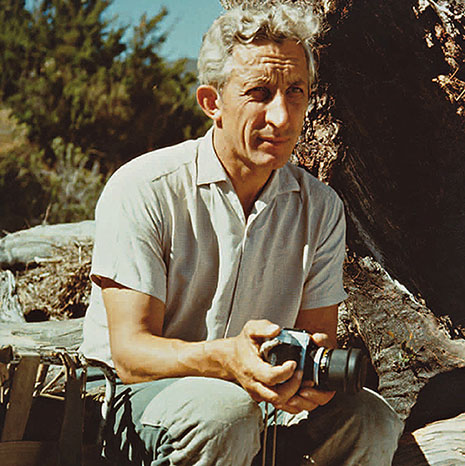

Truchanas cultivated his interest in photography through local camera clubs and soon had work published in Australian photographic journals. He worked in 35mm format, first in monochrome and later in colour, capturing the changes in light and tone that make southwest Tasmania such a dynamic landscape. We now associate Tasmanian wilderness photography with the precise, large-format work of Truchanas’s friend and protégé Peter Dombrovskis; Truchanas’s work is softer, perhaps more subtle, but his themes and composition were hugely influential.

In 1956, Olegas married Melva Stocks, Launceston born and a keen bushwalker. While it’s easy to romanticise Truchanas’s life, the job of raising a young family with Olegas frequently absent – bushwalking, campaigning, volunteering as a sailing instructor for the National Fitness Council – could be difficult, Melva told Cica. After fifteen years or so, Truchanas had assembled an unrivalled visual archive of Tasmania’s wilderness at his West Hobart home. In February 1967, when bushfires engulfed much of southeast Tasmania and fire raged through Hobart’s bush suburbs, Truchanas was at the Hydro office in the city centre. Pregnant with their third child, Melva attempted to control the flames, but fled as they took hold. The archive was lost, along with their home and possessions.

As new Hydro planning threatened the Gordon River area as well as Lake Pedder, Truchanas made numerous trips to re-photograph these areas. He also deepened his commitment to Tasmania’s nascent environment movement, and his growing profile as a conservationist put him at odds with his employer. Other Hydro employees, including Truchanas’s friend, engineer Ralph Hope-Johnston, were similarly conflicted. Cica discusses the surprisingly civil relations between the Hydro and conservationists at that time, describing how the Hydro’s long-serving chief executive Sir Allan Knight attended a fundraising exhibition of paintings and photographs for the Lake Pedder campaign in 1971 and bought a Max Angus watercolour of Pedder on Truchanas’s advice. But the conservationists posed no political threat to Knight at that stage. It was the formation of the movement’s political wing, the United Tasmania Group, which fought (albeit unsuccessfully) the 1972 Tasmanian election, that marked the turning point in the debate.

By the end of 1971, with work proceeding on the three dams that would eventually impound the largest inland body of water in Australia and submerge Lake Pedder, Truchanas commented to friends on his growing exhaustion. At the age of forty-eight he planned another arduous solo trip along the Gordon River. He had just been offered a job teaching photography, canoeing and bush skills at the new Tasmanian College of Advanced Education, and the prospect of leaving the Hydro’s employment delighted him. But he never took up the position. On 6 January 1972, preparing to launch his kayak into the Gordon River, he slipped, became trapped and drowned.

Cica notes that Truchanas’s artistic legacy became known to the wider Australian public through the 1975 publication of The World of Olegas Truchanas. The publication was compiled by the Tasmanian salon, undeterred by lukewarm responses from prospective publishers. The cosmopolitan Truchanas may have been amused by one publisher’s cringing advice not to include his name in the title. The first edition sold out in six weeks. In total, it sold a remarkable 40,000 copies and pioneered wilderness publishing in Australia.

Pedder Dreaming is a beautiful book, richly illustrated with Truchanas’s photography and the art and photography of his friends. Cica offers us much more than a biography; the book describes an important period in the development of Australian environmentalism, and it is a cautionary tale about the destructiveness of unchecked power. Truchanas escaped a brutal form of totalitarianism in Lithuania to find another, milder version in Tasmania. Has the susceptibility to a simple economic prescription changed? Contemplating the current battles over the Tamar Valley pulp mill, Cica recalls Truchanas’s speech at a Lake Pedder rally:

“If we can revise some of our attitudes towards the land under our feet; if we can accept the role of a steward, and depart from the role of the conqueror; if we can accept the view that man and nature are inseparable parts of the unified whole – then Tasmania that is truly beautiful can be a shining beacon in the dull, uniform and largely artificial world.” •