There can’t be too many places where you’d see Ross Garnaut and John Hewson wearing ID tags with ARTIST written on them. But at WOMADelaide, the Peter Gabriel–inspired World of Music and Dance festival held annually in Adelaide’s Botanic Park, someone in management has a sense of humour. Either that or they thought ECONOMIST just wouldn’t cut it backstage with De La Soul or the Violent Femmes.

Hewson and Garnaut were at the festival to talk about the economic opportunities offered by a green economy. They were billed as part of the Planet Talks – a series of talks about, well, the planet – headlined this year by the prolific Canadian academic and environmentalist David Suzuki. By all reports Suzuki slayed them; not necessarily in the same manner as the Femmes did on opening night, but he was pretty good all the same. One of his main points for locals in the audience was that he wasn’t all that excited about the SA government’s plans to enter what Bill Shorten calls “the international business of storing other people's nuclear waste.”

Suzuki was referring to the debate around premier Jay Weatherill’s royal commission into, among other things, setting up radioactive waste storage and disposal facilities in South Australia. The commission, which handed down its interim findings in February this year, estimated that the project, once it started, would bring in around $5.6 billion a year for the first thirty years and about $2.1 billion a year over the following forty-three. For an alleged rust-belt state never quite sure where its next dollars are coming from, the dollars look attractive. Suzuki’s argument, on behalf of the planet, was that while South Australia may be geologically stable now and storage of nuclear waste looks safe in the foreseeable future, the future is rarely fully foreseeable.

I’d missed Suzuki, having traded in his Saturday afternoon keynote for The Spooky Men’s Chorale. It wasn’t my original plan, but I’d been told that the men from the Blue Mountains were about the wackiest act on the program and shouldn’t be missed. They confirmed it with a rendition of Kasey Chambers’s “Not Pretty Enough” that left barely a dry eye out on the lawn; there’s something captivating about a bunch of middle-aged types, many of them bearded, melodiously and harmoniously enquiring as to whether they were pretty enough, or if their hearts were too broken, whether they cried too much, or if they were too outspoken.

Such is the vibe at WOMADelaide that it’s important to keep plans fluid. It’s the type of festival where you can set off for a must-see performance at a stage across the park somewhere and find you don’t make it because you’ve suddenly developed a liking for Serbian folk songs or Inuit throat singing along the way.

Back at Speakers’ Corner on Sunday, I staked out a spot in the Planet Talks tent awaiting Hewson and Garnaut while Kev Carmody provided the backdrop. His last tune was “From Little Things Big Things Grow,” the song he wrote with Paul Kelly about the Wave Hill walk-off by Gurindji stockmen in 1966, led by Vincent Lingiari, an event that will see its fiftieth anniversary in August later this year.

The title of the song would prove poignant, though the tenor of the discussion between Hewson and Garnaut, chaired by the Guardian’s Lenore Taylor, was more that big things needed to grow pretty quickly. A fossil-free energy future was inevitable and the world was leaving Australia behind in developing and nurturing renewables like hydro, wind and solar, areas where it ought to better exploit its natural advantages.

Perhaps Hewson’s biggest cheer – or was it a groan? – came when he mentioned how John Howard has said he prefers to trust his instincts when it comes to climate change. Hewson, a technocrat if ever there was one, was scornful: “Well, it’s not a matter of instincts; it’s a matter of science.”

On the topic of South Australia’s planned foray into the nuclear waste dumping business, Hewson called for a “mature debate.” Nuclear power isn’t a particularly viable option in Australia because alternative energy sources were more abundant and cheaper, he said, but storing other countries’ waste was one way of injecting long-term revenue into the state. Garnaut agreed. It sounded like a done deal from where I was sitting.

It had finally dawned on me that I was at a music festival listening to two economists talk about public policy, so I scarpered. Ladysmith Black Mambazo were coming to the end of their set on the main stage but I realised I wasn’t going to make it so I pulled up at stage two for Sarah Blasko. For those unfamiliar with the festival layout, stage two faces west and at 4 pm in early March in Adelaide, a gig staring into the western sun is a pretty short straw for a musician. Blasko, who was only barely surviving her own choreography, called it extreme sport.

I left early – I suspect Sarah would have too, given the chance – and headed back to the huge Moreton Bay Fig under which I’d last seen my children running barefoot with other people’s children. They weren’t there. I wandered off again and somewhere out the back, in the far northeastern fringes of Botanic Park, I caught a few tunes from Diego El Cigala, who, as I’d learned seconds earlier on the festival app, is “widely regarded as the world’s most exciting and innovative flamenco singer.”

I wove in and out of the throng to get close to the Sinatra of Flamenco, as he’s been dubbed, and experience his embrace of “gypsy fire with complex Cuban rhythms and a fresh take on Argentinean tango.” For someone with my interest in Argentinean tango, this came as quite a relief; it could do with a fresh take. El Cigala, a ludicrously handsome individual if you like that sort of thing, looked like he had enough gold on his fingers and wrists to buy my house a few times over.

My eighth-grade knowledge of Italian, coupled with my zero knowledge of Spanish, led me to the fluky conclusion that El Cigala was a nickname. Initially, with all that gypsy fire, I thought it might be Spanish for a cigar or cigarette of some sort, but upon googling “El Cigala” via the festival’s free wifi, I found that it means Norway Lobster. That was unexpected.

Also unexpected was Melbourne-based Marlon Williams & The Yarra Benders. Marlon, a New Zealander who Australians, more than likely, will claim as their own if he hangs around much longer, looks and sounds like a superstar in the making. In a musical sense, at least, he’s got a little bit of the Hank in him, as well as Tim and Jeff Buckley, Roy Orbison and Billie Holiday. In the immortal words of Molly Meldrum, if Marlon swings by your neighbourhood anytime soon, do yourself a favour.

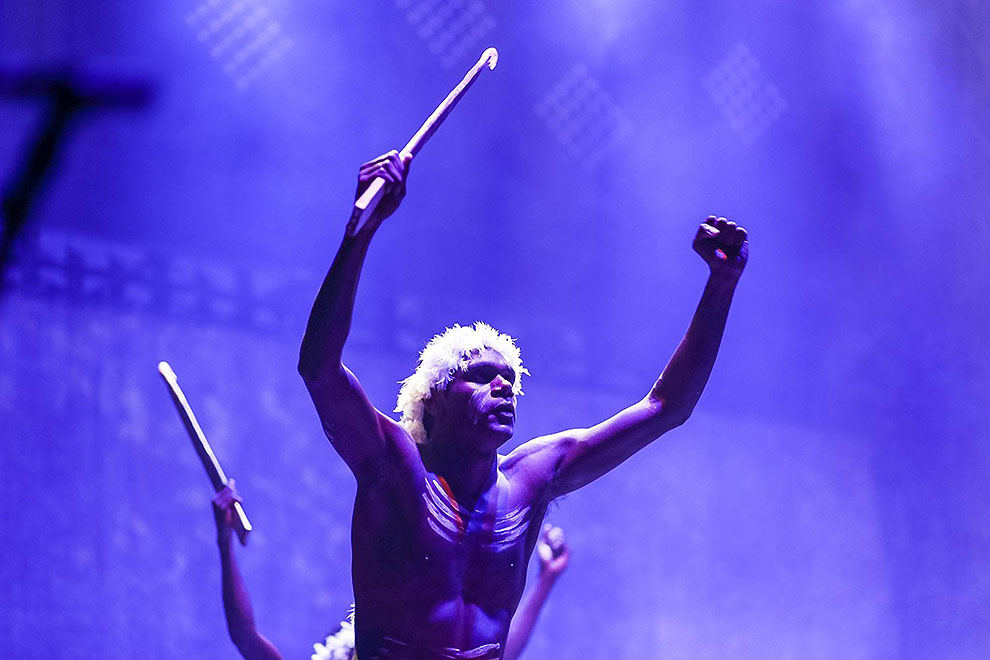

I skipped Calexico on the main stage; they’re not necessarily my cup of tea. But that’s probably the point of WOMAD: there are different cups of tea all over the place. One particularly good one was Djuki Mala, a group of Yolngu men from Elcho Island in northeastern Arnhem Land, a place that has spawned an inordinate number of brilliant Indigenous performers, including Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu, the Saltwater Band, and George Burarrwanga, the late lead singer of the Warumpi Band.

Known previously, and far and wide, as the Chooky Dancers, Djuki Mala packed out stage two, beginning with traditional dances from home before exploding into a medley of high-energy, high-farce numbers with no connection other than that they were all hilarious. Gene Kelly’s “Singing in the Rain” will never be the same. Bollywood also got the Yolngu treatment.

The Sunday at WOMADelaide that started with the two economists finished with Ludovic Navarre, otherwise known as St Germain, the French electronica star from the mid to late 90s who was back in the studio and in front of live audiences again after a fifteen-year absence. Despite being right up the front under the speakers, my interest wasn’t held for long. It wasn’t Ludo’s fault. It had been a long day. Actually, it had been three long days, and Monday was still to come. •