White House press secretary Sean Spicer has had a busy week. Having just put the inauguration numbers squabble behind him, he found himself defending Donald Trump’s reprise of his earlier assertion that “millions” of illegal immigrants voted for Hillary Clinton. This time the president is reported to have been more precise: there were three to five million of them – and, according to a tweet late last year, Clinton won three states with their help, “Virginia, New Hampshire and California.”

If those figures were accurate, they would represent a high proportion of the total nineteen million turnout in those states. Strategically subtract five million votes across the three states and they all move to Trump’s side of the ledger. But the most important driver of the new estimate, of course, is the amount by which Clinton outpolled Trump across the nation: 2.9 million. The number of fraudulent votes needs to be bigger than that.

Being seen as the less-popular candidate obviously irks the new leader. Since the first American presidential election in 1788, only five vote-losers have emerged victorious. The 2016 losing margin of 2.1 per cent was second only to 3 per cent in 1876.

In Australia, we’ve had five such outcomes at the federal level since the emergence of the two-party system around 1910: in 1954, 1961, 1969, 1990 and 1998. (1940 could conceivably join that list; analyst David Barry estimates the national two-party-preferred split as 50–50.)

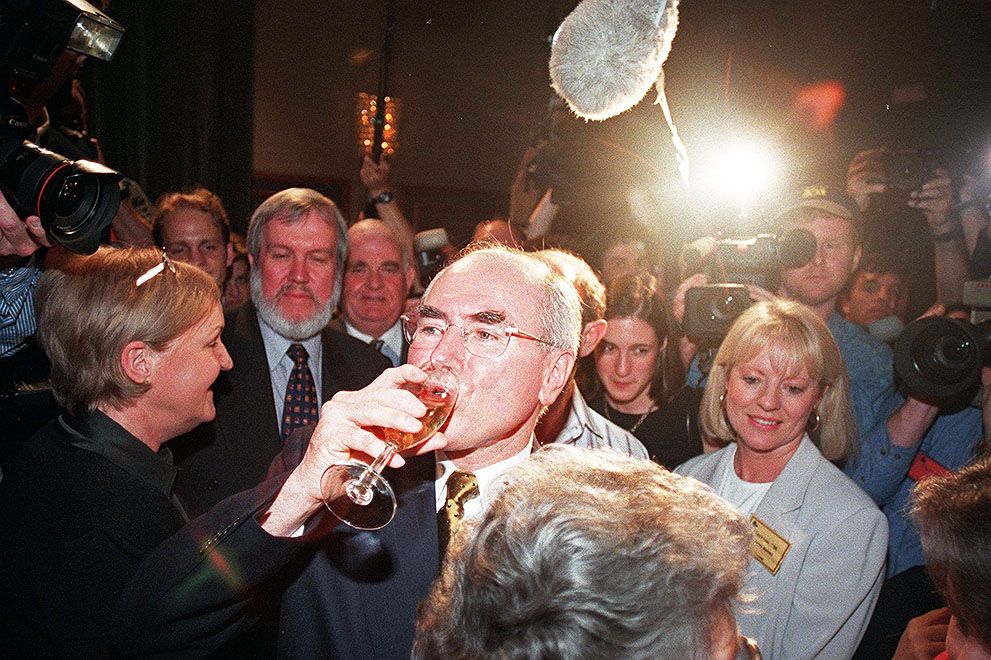

The most recent occurrence, the first re-election of the Howard government in 1998, holds the record, with Labor receiving 2 per cent more of the vote than the Coalition.

Addressing the National Press Club in the wash-up eighteen years ago, Liberal Party federal director Lynton Crosby explained that the ambition was to “win the most lower-house seats… that is what our campaign was geared towards.” If the goal had been to win “a majority of the two-party-preferred vote… then you would run a completely different campaign.”

Which is, of course, completely true. The campaigning action takes place in the electorates that might conceivably change hands, just as in the United States it’s all about the “swing states,” those that could go one way or the other. (State size, and hence electoral college votes, is also a factor.)

But Crosby’s implied assumption that the Coalition’s strategic prowess would have prevailed in a national vote contest is certainly open to question. Political commentators mostly propagate the mythology of the genius campaigner – the campaigner who can win the vital seats and avoid wasting resources elsewhere – but a lot of post hoc logic and back-scratching by party figures goes into constructing these legends.

After November’s US election, the president-elect made the Crosby argument with characteristic grandiosity. Leaving nothing to implication, he tweeted that “if the election were based on total popular vote I would have campaigned in N.Y. Florida and California and won even bigger and more easily.”

The nature of the “popular” or “national” vote differs between our two countries. Australia has preferential voting; America uses what is, in effect, first-past-the-post in differently sized, weighted electorates. Voting is compulsory here and optional there, with obvious repercussions for turnout. Most importantly, ours is a parliamentary system.

In the US, voters choose from a list of individuals for the position of president. The electoral college, which technically chooses the president, was designed in part as insurance lest the electors select someone unacceptable. Today, that function is anachronistic; the winner-take-all rule in nearly all states, which delivers 100 per cent of electoral college votes on even a meagre plurality, is the chief potential distorter of results.

On this side of the Pacific, citizens vote, at least in theory, for local members rather than leaders, and the national party vote is a construct. Our original Constitution, and early electoral acts, contained no mention of parties, let alone leaders.

The two-party-preferred vote has been with us since preferential voting was introduced before the 1919 election, though it didn’t enter the popular consciousness until it was popularised by psephologist Malcolm Mackerras in the late 1960s. The national two-party-preferred vote shows the proportion of all voters who ranked Labor higher than the Coalition, versus those who did the opposite. Like the national popular vote in the US, it is of interest, but ultimately irrelevant to the outcome of an election under the current system.

Does it matter if the loser of the national vote emerges victorious? I believe it does. One vote, one value is supposed to be a tenet of fair elections. And, like it or not, the vast majority of electors are driven by support for a party rather than for their local candidate.

In the US, the solution would be reasonably straightforward: abolish the electoral college and move to direct election of presidents using first-past-the-post, two-round or preferential voting (what they call the “ranked ballot”).

The solution for Australia is not so obvious. Since 1991, South Australia’s Election District Boundaries Commission has had a legislative duty to take account of “fairness” in drawing up boundaries, with the aim of ensuring that the winner of the statewide vote emerges with the most House of Assembly seats. In this aspiration it has failed miserably: the current Labor government, in office since 2002, has only won the popular vote once at the past four elections. Most egregiously, Labor survived in 2014 with just 47 per cent of the vote to the Liberals’ 53 per cent.

There is one way to guarantee that all votes are counted equally, and to eradicate the fetishisation of particular electorates and demographics, and that’s by employing proportional representation for elections to the House of Representatives. As I’ve previously written, it would have the added likely benefit of addressing the inter-cameral gridlock that characterises modern Australian politics. •